The pandemic has contributed to a lot of breakups, but one of the more shocking splits came when the National Zoo announced in February that it was parting ways with FONZ, the nonprofit that for 63 years had been nearly indistinguishable from the zoo. Anytime you rented a stroller, perused the gift shop, or asked for directions to the ape house, chances are it was a FONZ staffer (the name stands for Friends of the National Zoo) who assisted you. The free-admission zoo is part of the Smithsonian, but FONZ was set up to augment the feds, both financially and logistically.

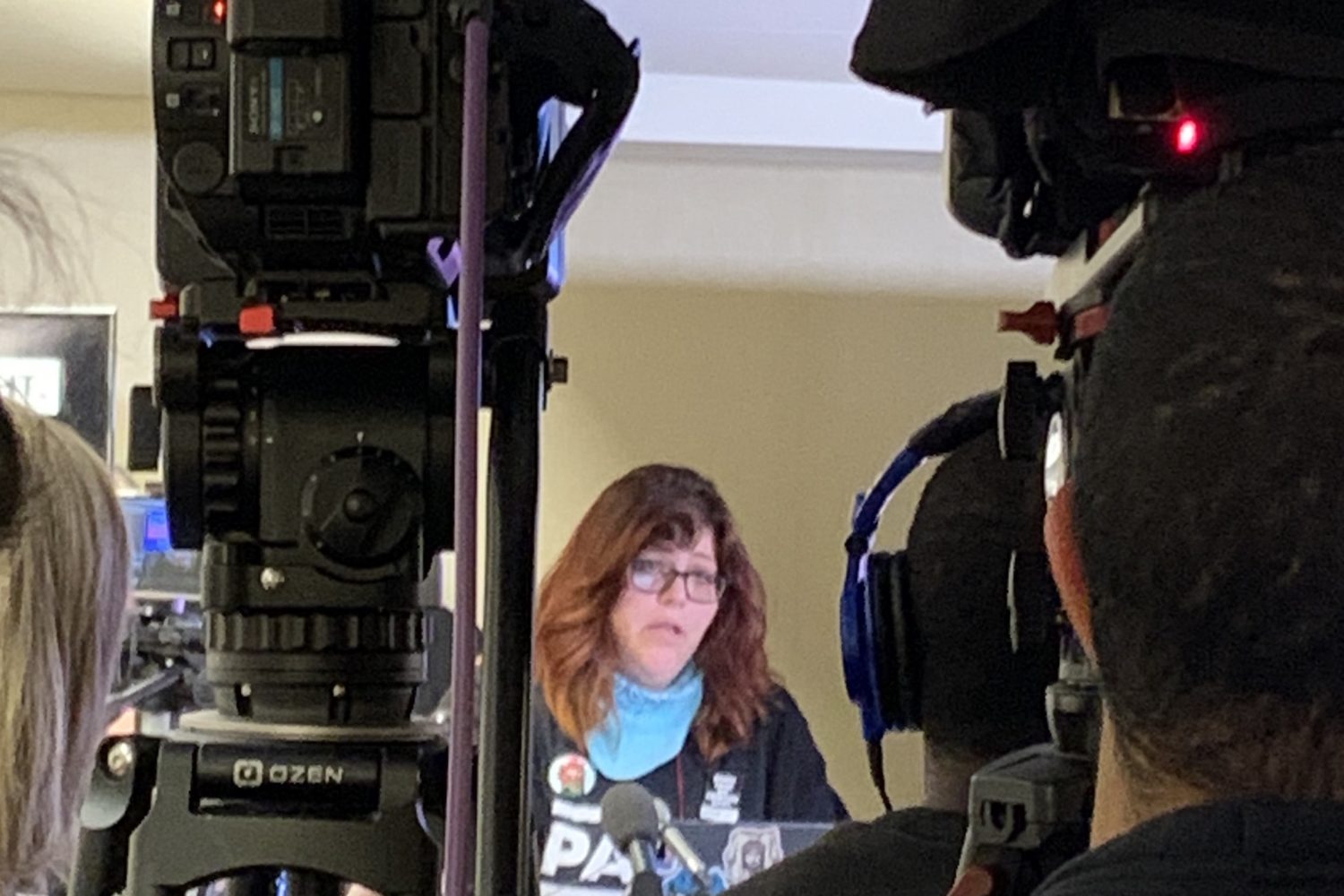

However, when the pandemic forced the zoo to temporarily close, the ensuing financial pressure put an insurmountable strain on the relationship. In the end, it was like a lot of divorces, with neither side quite agreeing about what went wrong. The zoo said it couldn’t afford FONZ anymore. FONZ said it came up with a new arrangement that was ignored. “We were fighting hard to try to save this little nonprofit organization that we all thought was such a gem for the DC community,” says Lynn Mento, who ran FONZ for six years before it shut down due to the split. “It was quite stressful. It was clear that they didn’t want to be friends any longer.”

After the divorce, a question remained: Could FONZ’s work continue in a new form? Mento now has the answer. Recently, she relaunched it as a much smaller operation called Conservation Nation. Gone are FONZ’s offices at the zoo; the group works remotely. And its peak-season staff of about 250 has been slashed to just nine.

Though it’s no longer selling stuffed pandas in the zoo gift shop, Conservation Nation is carrying on another part of FONZ’s old mission: saving wildlife around the world. The new group is focusing on funding and supporting conservationists from diverse and underprivileged backgrounds. “Wildlife is being destroyed at a horrifying rate,” says Mento. “We need every smart voice at the table. But that table needs to be larger and representative and diverse, and it’s not.” Conservation Nation has already launched a grant program, awarding money to ten recipients for projects as varied as saving the endangered pink dolphin and researching the impact of climate change on owls.

“The more diversity we can bring to the field, the more well-rounded [our] view of how to solve the issues that we have when it comes to the environment,” says T’Noya Thompson, one of the grant recipients, who will use the funding for a study of tropical birds in her native Bahamas. “I don’t know if I would’ve found another opportunity to launch a project like this.”

Conservation Nation will also be educating kids from underserved communities about career paths in conservation. The organization is partnering with DC public high schools and the Washington Boys and Girls Club for its pilot program, set to start in January. Mento says the particulars are still in the works, but that the teens who participate will connect with Conservation Nation’s grant recipients, and go on field trips to experience nature and see wildlife. “The goal is to open their eyes to the fact that we need them, the world needs them, wildlife needs them,” says Mento. “They deserve a spot at the science-conservation table.”

Mento has tapped leftover FONZ money for the new organization, and is also looking for new funding. Meanwhile, the zoo has covered FONZ’s old duties with Smithsonian staffers. Mento says she doesn’t have lingering bad feelings. Would she ever be open to renewing some kind of partnership? “Absolutely,” she says. “I would welcome it.”