If you ever visit Gordon Kit’s house, he just might invite you to get in the shower. That spot, the retired patent attorney will explain, is the best place to understand a big reason why he spent the past four years working to win historic designation for his house. When you peer through the bathroom window, you can get a clear view of the neighboring lot, where a cream-colored behemoth is currently under construction.

That Colonial-ish house is replacing the 1960s home that used to occupy the space, a midcentury-modern structure with walls of glass and a pool that evoked Palm Springs. But then its owner died and a developer razed it. Kit was determined to avoid the same fate for his midcentury-modern in DC’s Palisades. “If you look at the neighborhood, all these old houses have been torn down and they’ve built McMansions—these unattractive things,” he says.

Of course, in a city famous for ornate Victorian rowhouses and grand neoclassical buildings, plenty of people would cast a similar disparaging eye at Kit’s house. But midcentury buildings have gotten far more popular over the last decade or two, cherished by a growing segment of architecture fans who appreciate the clean lines and low-slung profiles.

At the same time, they keep being torn down. Several other DC homes by the architect who designed Kit’s house—lauded modernist Jean-Pierre Trouchaud—have already been destroyed. The house that used to be next door to Kit’s was designed by a notable firm called Diegert and Yerkes. Down the street, a 1950s modern once featured in Better Homes & Gardens got the wrecking ball a few years ago. In Forest Hills, a midcentury-modern by Brown & Wright—the first architecture firm in Washington to be racially integrated—was bulldozed, then replaced with a 17,000-square-foot limestone villa that’s currently on the market for $12 million.

So Kit had good reason to seek protection for his own home. At first, he didn’t know how to go about it; the process of getting a historic designation is complicated and a bit opaque. So he sought out help from the DC government. That’s when he got in touch with a woman named Kim Williams, who, it turned out, was eager to take up what she considered an urgent task: saving these underappreciated residences throughout the District.

Williams’s job description—architectural historian at DC’s Historic Preservation Office—brings to mind images of red brick and white marble, the kinds of prewar buildings that typically get the preservation treatment. She has spent 20 years working for the District government, first as a contractor, then as a full-time employee, and her current duties as the city’s National Register coordinator involve assisting homeowners who are seeking historic status, as well as working to get local landmarks added to the National Register of Historic Places. She tends to deal with buildings that were erected before many current DC residents were born.

But Williams also likes to assign herself in-depth research projects, which is where the midcentury-moderns come in. She first became interested in documenting these homes a few years ago, when she was working on another project and noticed concentrations of midcentury-moderns in some of the neighborhoods in upper Northwest DC. The architecture was distinctive, she says, “and yet they hadn’t been recognized in any official capacity.”

It was around the same time that Gordon Kit contacted her. Williams had only ever received one other inquiry from the owner of a midcentury-modern, and that had been more than a decade before. “I got very excited about it,” she says. “I knew we were losing these types of houses, and I knew [Kit’s] house would help us understand them better.” She connected him with the DC Preservation League, a nonprofit that could undertake the intensive research he needed to apply for landmark status.

Williams became curious, too. Not long after, she decided to start making a database—the District’s first effort to survey its stock of midcentury-modern homes. She hopes to build the case that many deserve the same protections afforded to Wardman rowhouses, Beaux-Arts mansions in Kalorama, and other types of residences more commonly thought of in Washington as landmarks. All midcentury-moderns now meet the 25-year minimum age requirement in DC to qualify as historic, and most meet the national requirement, which is generally 50 years.

Williams’s process is about as low-tech as it gets. She uses archived building permits and city tax records to isolate houses built between the 1940s and ’70s, then heads to Google Maps and pulls up the street view. This method yields a lot of false positives—postwar Colonial Revivals and ranches that aren’t what she’s looking for. But there have still been plenty of exciting discoveries, such as when her part-time intern—the only other staffer helping with the research—sent her a listing for a modern house for sale off MacArthur Boulevard. When Williams plugged it into Google Maps and zoomed out, she saw that it was surrounded by nine others—an entire development of midcentury-moderns.

So far, Williams’s survey includes more than 230 addresses. Some were well known long before she started this project, such as a pair of houses on Chain Bridge Road by the Architects Collaborative—the world-famous firm of Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus school—and a residence in Forest Hills designed by Chloethiel Woodard Smith, one of Washington’s most significant modernists (and a rare woman in the field). But Williams has now added dozens of others, most of which have never received any recognition at all.

Though she initially focused on upper Northwest, Williams has since expanded her search to Northeast DC’s Brookland, another neighborhood with pockets of modernism—much of it designed by professors from Howard University’s architecture department.

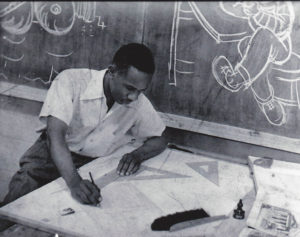

Williams has tracked down eight modern Brookland houses designed by Black architects, including several by Robert Madison. Before he moved to DC, Madison was the first licensed Black architect in Ohio. Howard hired him as a professor in the 1950s, and he also started a solo practice. “There were not a lot of Black architects who were out on their own,” says Madison, now 98. “When you become an architect, you have to depend on clientele, and there were not a lot of African Americans who had enough money to build a house for themselves.”

Madison recalls designing about a half dozen modern houses locally, most in Brookland (Williams has tracked down three of them) and a couple in Northwest (she hasn’t found those). Madison says these commissions came from a Black-owned development company that hired him to build spec houses: “They wanted something totally different.”

Having studied with Walter Gropius at Harvard and with Le Corbusier in Paris, Madison was more than happy to stray from DC’s traditional aesthetic. He also designed public buildings, such as Brookland’s Church of the Redeemer Presbyterian. After moving back to Ohio, he started another firm that’s been involved in huge projects such as the Cleveland Browns’ stadium and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. But his DC work remains a meaningful piece of his career. “The houses were the first project I ever designed that got built,” he says. Even so, they could all be torn down at any moment—unless the homeowners decide to put in the work to have them preserved.

To get a DC house declared historic—that is, permanently protected from the bulldozer—you have to follow a series of steps. First, figure out if it meets the basic criteria (which can fluctuate from one neighborhood to another). Next, do the research mandated by the application, including finding out about the house’s architect and past residents, learning how it fits into the broader history of its neighborhood, and articulating what makes the design so consequential. Finally, present a compelling case to the city’s Historic Preservation Review Board, the outpost of officialdom whose members make the ultimate call. If your house wins the designation locally, the DC Historic Preservation Office can then opt to nominate it for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places, a mostly honorary recognition that doesn’t provide any additional protections.

But people who want to slap the historic designation onto modern residences confront a particular challenge: While the officials who rule on applications understand the context in which to evaluate, say, Federal or Victorian buildings, they don’t yet have such a framework to judge midcentury-moderns.

Williams’s survey is designed to remedy that, providing preservationists with an understanding of how to evaluate whether a modern house is worthy of protection: Does the use of materials, for example, or the way the interior integrates the outdoors generally comport with the spirit of DC midcentury-modernism? (Houses can also be labeled historic because their architects or owners were somehow notable, another factor she’s including in her database.)

Of course, there’s a good reason a homeowner might not want a house declared historic: Having your home designated a landmark can limit your ability to renovate, leaving you stuck with dated amenities—and shrinking the price when it’s time to sell. In theory, preservationists can seek landmark status for a house without an owner’s consent. But that’s not Williams’s preferred method of doing business. “I don’t want to get into this in a confrontational way,” she says. “We want people who really appreciate midcentury-modernism, who really appreciate their house. The more we can get them to designate their own properties, the less threatening designation can be to others out there.”

One of the biggest impediments to this work, Williams says, is that many owners aren’t aware of their home’s significance. Eventually—once she’s confident that her research is solid enough—she’ll start writing letters to inform them of their house’s place in Washington history.

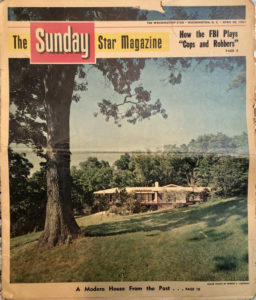

Unfortunately for landmark-seekers, getting historic status for a Jetsons-era home requires some distinctly byzantine paperwork. Just ask Gordon Kit. Earlier this year, his house officially won both local and national historic designation, which means it has been placed on the DC Inventory of Historic Sites as well as the National Register of Historic Places. It’s only the second modern residence in the District to earn either status. (The first was the William L. Slayton House in Cleveland Park, one of only three known houses in the world designed by I.M. Pei.)

Kit’s 57-page application went into exhaustive detail about his home’s design, previous owners, and architect. After Williams referred Kit to the DC Preservation League, the nonprofit group put the whole thing together pro bono. Otherwise, Kit says, he would have had to spend thousands of dollars hiring his own architectural historian.

Kit’s path to preservation had quite a bit to do with the house’s non-architectural history. It was built in 1957 by David Bazelon, who soon became chief judge of the US Court of Appeals for DC. Bazelon sold it to Democratic senator George McGovern, who owned it from 1969 to 1980, a period that included his run for President. Kit knew about the former owners, in part because he found McGovern campaign posters and other personal items when he moved in. The impressive past residents were just another reason he wanted so badly to protect the place.

Not every house has that kind of pedigree, of course, so Williams is hoping her research will help convince review boards and members of the public that this kind of architecture is worth saving on aesthetic grounds. After all, Williams herself once needed convincing. The part of Chevy Chase where she and her architect husband live is full of midcentury-modern homes, but she admits it took her a while to warm to the look. “My appreciation for them has grown,” she says. “They’ve aged. I’ve aged. Our perspectives change over time.”

To contact the DC Historic Preservation Office about your own mid-century modern home, send an email to historic.preservation@dc.gov.

This article appears in the November 2021 issue of Washingtonian.