When I ask indie film director Dan Mirvish for an interview, he immediately confesses to breaking into the Watergate. It’s the first thing he tells me—I’m not even recording yet.

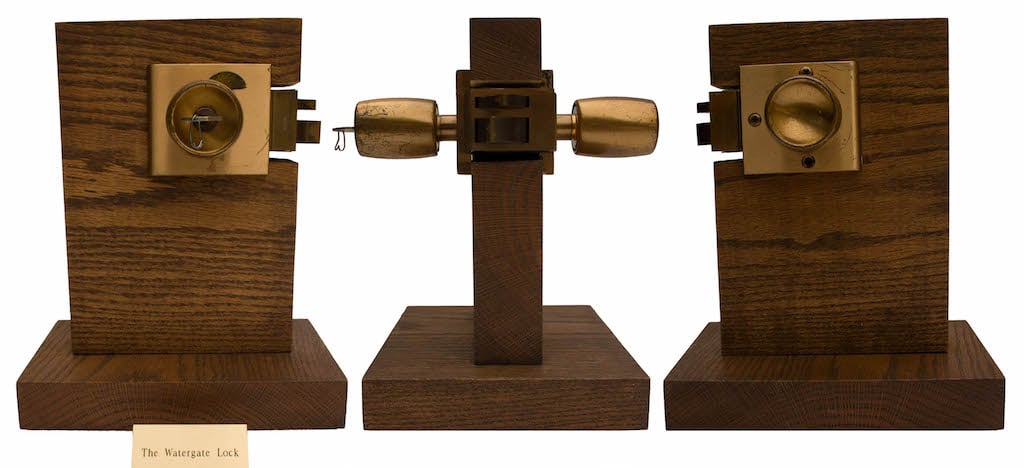

This allegedly occurred last week, after the DC premiere of his new Watergate comedy, 18 ½, now in theaters. Mirvish says he went to the bar at the Watergate, then snuck onto the building’s roof. Along the way, he posed for a selfie with a door—one that resembles the iconic door that began the unraveling of the Nixon presidency, the one whose taped lock alerted a security guard to the break-in at the Democratic National Committee.

Like the burglars, Mirvish planned to tape the lock. “But I didn’t need the tape,” he says, “because it didn’t lock.” In the picture on his phone, the door doesn’t seem to have any bolts. “Maybe they want people to break in,” he says with glee.

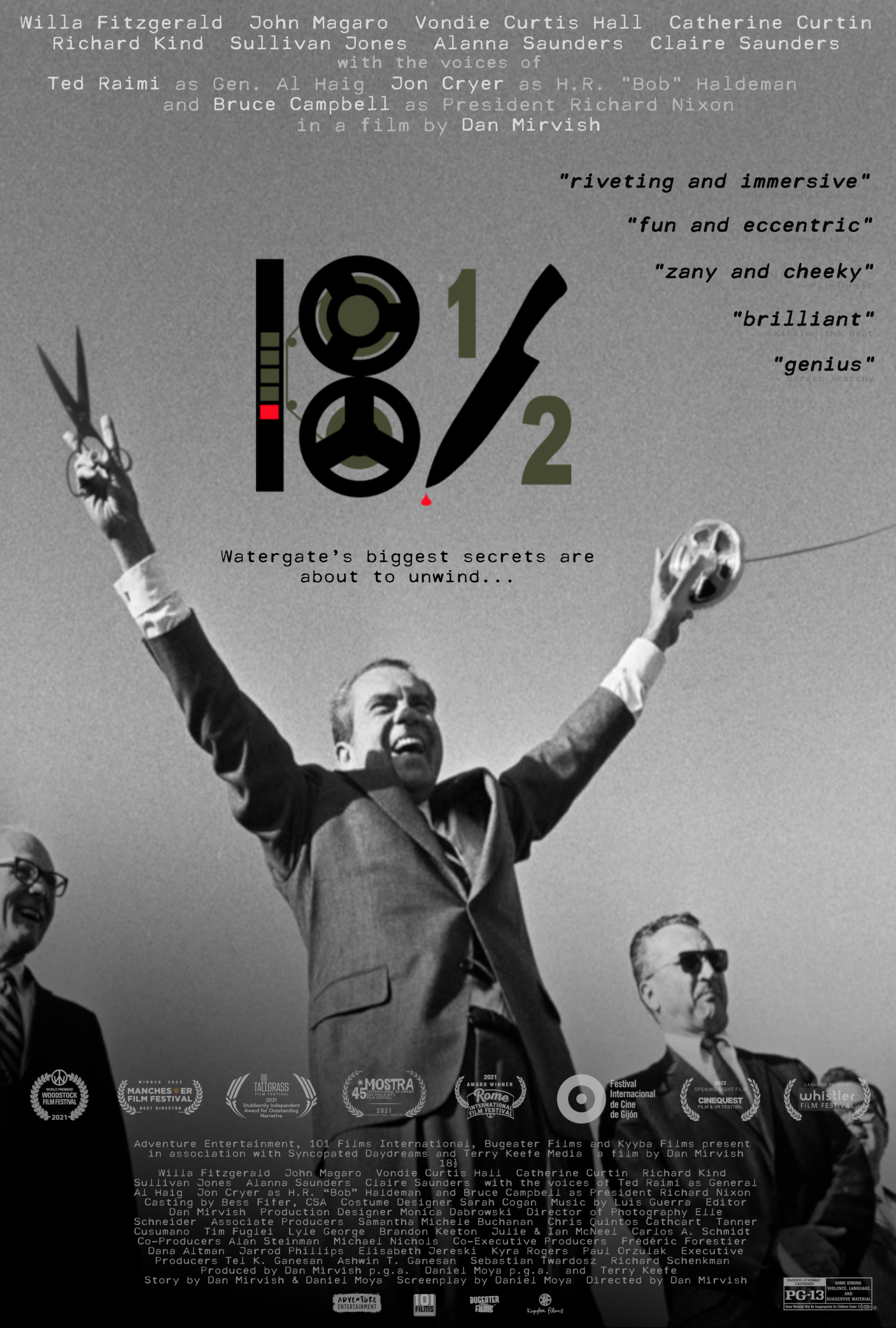

Mirvish and I are chatting on the sidewalk outside the IFC Center in New York’s West Village. He’s wearing a river-guide hat and a sandwich board made of movie posters for 18 ½. The posters show a black-and-white Nixon, fingers raised in his iconic V signs, with a pair of scissors and a reel of tape photoshopped into either hand.

The poster nods to an enduring mystery of Watergate: three days after the break-in, Nixon and his chief of staff met for two hours in the Oval Office, but in the tape of that meeting, there’s an 18-and-a-half minute gap. It’s a block of dead air surrounded by normal conversation; clearly, that section was erased. “Nobody knows what’s in that gap,” Mirvish says. “They were talking about Watergate, we just don’t know what they said—and no one ever will know, because they’re all dead.”

Mirvish’s film is an alternative history: Connie, a low-level White House typist, is transcribing an Office of Management and Budget meeting when she stumbles into a recording of Nixon listening to the missing tape. He’s commenting on how bad it looks for him and how it’s got to be erased, even though it’s under subpoena. (“There really are tapes of Nixon listening to his own tapes,” Mirvish says, “so it’s plausible.”)

This is 1974—America is feverishly obsessed with Watergate—and Connie decides to leak the tape to the press. She ferries it across the Chesapeake to a clandestine meeting with a Times reporter at a diner on the Eastern Shore, but the reporter’s tape player is broken. As they search for a replacement, they encounter a madcap ensemble of hippies and swingers, a conspiracy that links Wonder Bread with Howard Hughes, and a whole lot of bossa nova. The film is paranoid, slapstick, and a bit surreal.

“As far as I can tell, this tape has never been transcribed,” Mirvish says of the full two-hour conversation between Nixon and his chief of staff, Bob Haldeman—the one with the missing 18-and-a-half minutes. To research the film, Mirvish pulled the tape from the Miller Center at UVA and made a discovery: about two minutes after the gap ends—after Nixon has presumably just discussed Watergate—Haldeman mentions the movie The Hot Rock, a Robert Redford hit about a bungled diamond heist. “It’s kind of like this thing here,” Nixon replies, laughing. “They screw everything up.”

“This is three days after the burglary, and they start laughing about it,” Mirvish says in disbelief. “They were self-aware enough to be laughing at Watergate—like, they knew.” White House records show that Nixon actually watched The Hot Rock at Camp David a few days later—in fact, he watched it the day after a different conversation with Haldeman, in which they plotted to thwart an FBI investigation into the Watergate break-in. (This tape would later become the investigation’s smoking gun.) Mirvish finds it delightful that, in the midst of concocting the cover-up that would later end his presidency, Nixon watched a movie about bumbling diamond thieves, perhaps to make sense of his own situation. Everything is going wrong, Mirvish says, and “they’re like, ‘yeah, let’s watch that heist movie!’ ”

In the ’70s, Watergate was a national tragedy—a swift end to America’s postwar optimism, an injection of bitter cynicism and suspicion into the nation’s political life. Hence the many prestige Watergate dramas: All the President’s Men, Frost/Nixon, and Oliver Stone’s Nixon, among others. Watergate comedies are a rarer breed. There’s 1999’s Dick, in which the anonymous source of the Post’s Watergate reporting turns out to be two teenage girls. And then there’s 18 ½.

“I don’t know why more people don’t find the humor in Watergate,” Mirvish says. “It’s hard not to be funny with it.” To research the film, he listened to many hours of Nixon tapes, found them hysterical, and then did something daring: he wrote his own version of the lost 18-and-a-half minutes. At the film’s climax, the conversation plays in the foreground on reel-to-reel: there’s talk of Howard Hunt, Operation Gemstone, Nixon’s mistrust of the FBI, the kidnapping of Martha Mitchell, and the I.T.T. affair—a Nixonian corruption scandal that dominated headlines before Watergate asked America to hold its beer.

“We threw in a little bit of the kitchen sink,” Mirvish says, “the biggest hits.” At one point in the film’s version of the tape, Nixon (who is voiced by Bruce Campbell) makes an offhand remark that shaking Mark Felt’s hand “felt like a weasel.” All of this, Mirvish insists, “is as plausible as any other thing—it’s no goofier than what was on some of the actual tapes.”

Screwball as it is, Mirvish’s weird political satire has apparently resonated worldwide: “The Brazilians were like, ‘Oh, this is really about Bolsonaro.’ And in England, they were all like, ‘Oh, this is just like the Boris Johnson scandal.’ Then in Spain, they were like, ‘Oh, this reminds us of Franco.’ ” Of course, in the United States, many viewers think of Trump. While that administration was full of bizarre quasi-humor—Trump once threw a handful of Starburst candies at Angela Merkel during the G7, telling her “don’t say I never gave you anything,” for instance—it’s tough to imagine a Trumpian comedy. “Maybe that’s the advantage of being 50 years away,” Mirvish says of Watergate.

As we’re wrapping our interview, Mirvish hands me a seven-inch record sleeve that holds a square of floppy, green, translucent plastic on which two of the film’s bossa nova numbers are printed. (It’s apparently from a Czech factory that used to “print little flexible records onto medical X-rays during the Cold War,” back when people were smuggling in rock and roll from the West.) Mirvish signs the sleeve “You are not a crook.”

This record encapsulates the rigorously weird aura of Mirvish’s whole endeavor. The bossa nova songs evoke an obscure CIA conspiracy buried in the film’s plot, and on the back of the sleeve are some song lyrics that Mirvish wrote himself, including one about eating Wonder Bread: “Wonder what will happen when it kicks in? / You’ll make sweet love with Richard Nixon.”