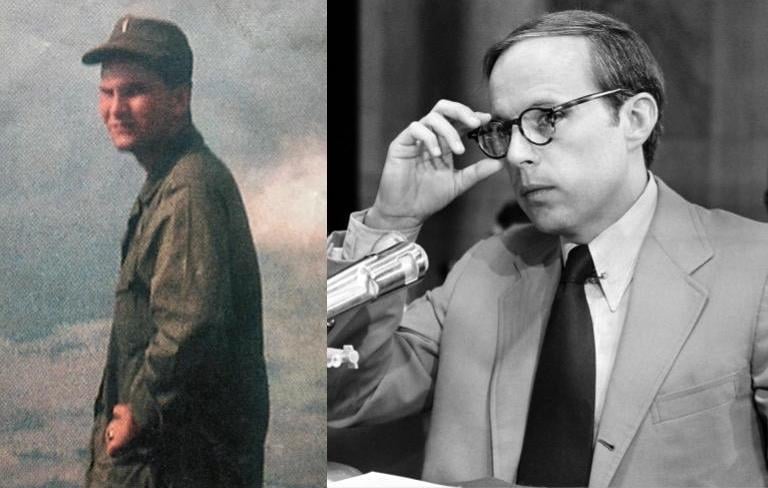

In the summer of 1973, my uncle, John W. Dean, was living in a townhouse in Burke and raising his young family. A helicopter pilot in the Vietnam War, he worked as an air-traffic controller at the Washington Air Route Control Center in Leesburg.

The previous winter, his beloved Washington Redskins, for whom he moonlighted as sideline injury reporter at RFK Stadium, had stomped the Dallas Cowboys 26-3 to make it to the Super Bowl. He was in his early 20s, and life was good.

Then the phone calls started.

“Are you John W. Dean?” came a menacing voice over the line.

“Yeah.”

“I’m gonna kill your snitching rat-fink ass.”

“I think you’ve got the wrong John W. Dean.”

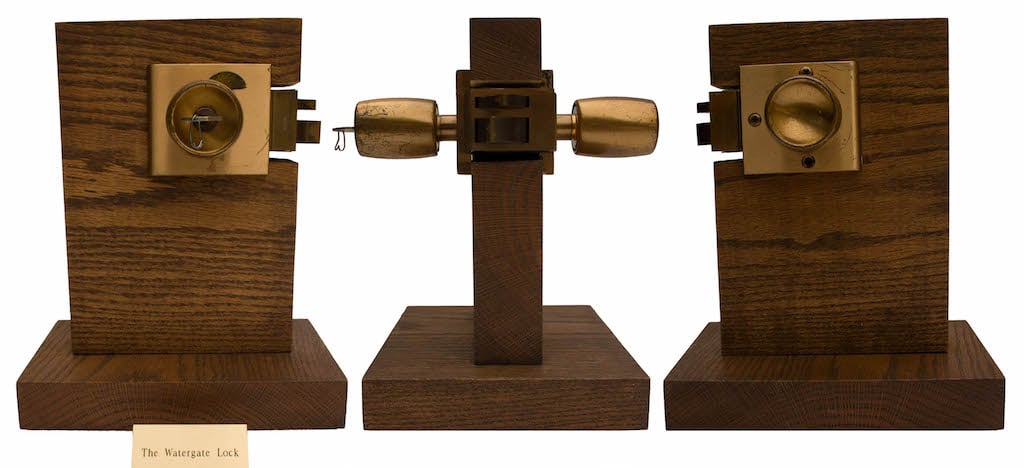

The Watergate scandal had reached high tide, and the rats were abandoning the sinking ship that was the Nixon Administration, a year after the bungled burglary and the subsequent cover-up.

Chief among them was White House Counsel John W. Dean, the sycophant-turned-snitch that the caller said he wanted to kill. This John W. Dean, an up-and-coming GOP minion previously unknown to most Americans, lived in Old Town Alexandria. He had an unlisted phone number and was somewhat protected from unhinged wackos in those pre-Internet days. So my uncle was fair game in the well-thumbed pages of the Northern Virginia White Pages for the visceral death threats that came regularly for a while, back when harassment meant uber-creepster heavy breathing straight from a ’70s cop show. (Mannix, anyone?)

The embattled politico’s full name was John Wesley Dean III; my uncle’s was John Wayne Dean. Though their names were similar, this pair of John W. Deans couldn’t have been more different. In fact, they came from two different Americas—or more precisely, two different Washingtons—that are still with us today.

The so-called “official” Washington, the nation’s capital, is fueled by entitlement and money and connections in high places. The other Washington, which locals call home, is grounded in effort and grit and kin and pride of place.

John Wayne Dean was the son of a machinist who worked at the Navy Yard in DC and the grandson of a plasterer from Annandale. As a freshman he earned a varsity letter on the wrestling team at J.E.B. Stuart High School. He and his classmates would sneak underage into DC clubs like Shadows, where they saw local bands like the Mugwumps, later known as the Mamas & the Papas.

After graduation, John Wayne turned down two college wrestling scholarships because he was sick of school. Instead, he joined the Army and did a year-long tour of duty in Vietnam. In 1967, while assigned to the 121st Assault Helicopter Company, he earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for 15 trips to rescue under heavy fire more than two dozen wounded from a 500-pound bomb crater.

John Wesley Dean spent the war years in another kind of combat, diligently climbing up the corporate and government ladders. Like many who come to Washington for the power and the glory and “a great title,” as he recently told the Washington Post, John Wesley was a child of privilege. He came from Ohio; his father was a well-heeled businessman. Reared in private schools, he received a law degree from Georgetown University in 1965. He joined a DC law firm but was soon fired for what the firm first called “unethical conduct” but later, under political pressure, described as a “basic disagreement” over the scope of an associate’s job.

In July 1970, at 31, the exact age at which the hippies warned that nobody should be trusted, John Wesley was appointed as counsel to President Richard M. Nixon. One of his duties, among many sordid and unscrupulous tasks, was to help compile an Enemies List of perceived political opponents, including such antiwar activists as Paul Newman.

In that summer when John Wayne began receiving death threats meant for John Wesley, the latter had made the cover of Time magazine twice, with such teasers as “Dean Talks” and “Will Nixon Survive Dean?” The answer, of course, was no, and it was Dean’s June 1973 testimony—detailing how Nixon knew about the scandal and aided in the cover-up—that was the beginning of the end for the 37th president.

An issue of Time featuring John Wesley on the cover was mailed to John Wayne, with instructions to autograph it and send it back. It was apparently from a hustler with an eye for the collectibles market.

My uncle threw the magazine away.

Now, with the 50th anniversary of the Watergate break-in, The Washington Post and their big-media cohorts are taking the obligatory victory laps. Amid this nostalgia-fest is yet another re-emergence of the lionized, saintlike John Wesley. The disbarred-lawyer-turned-investment-banker-turned-pundit-for-hire has spent most of the last half-century burnishing his image as a brave whistleblower and savior of democracy, not just a feckless Republican Party hack out to save his own skin.

As long-time darling of the Washington establishment, John Wesley has become the go-to expert and explainer on All Things Watergate, especially now. The headline of a typically fawning puff piece in the June 2 Washington Post exalts him as Watergate’s “Golden Boy.” The article hails the withered 83-year-old as a sage and “touchstone for political morality.” It’s all part of a publicity blitz to promote his four-part special starring himself, Watergate: Blueprint for a Scandal now airing on CNN, where he has appeared as a reliable partisan shill for years.

It is the carefully curated Golden Boy image—relentlessly milked by John Wesley into a cottage industry and enabled by journalists—that most rankles John Wayne. The never-ending redemption act reeks of blatant hypocrisy, as if some head-hunting goon on the Cowboys or Eagles known for late hits keeps winning the NFL Defensive Player of the Year award. “He’s selling himself as a big hero and everybody’s expected to buy into it,” says John Wayne, a self-described independent with equal disdain for the far right and the far left. “He was a piece of shit then, and he’s a piece of shit now.”

For John Wayne, the unforgivable sin of John Wesley wasn’t his blind ambition (the title of his bestselling, self-serving 1976 memoir) or his craven betrayal of the man who hired him to do his dirty work. “Forget the disloyalty and deceit it took for him to turn on Nixon,” says John Wayne. “My way of figuring it is that he broke the code of lawyer-client privilege and confidentiality, and that was enough for me.”

To those who excuse this particular ethical breach as an example of putting the good of the country above the law—Dean was disbarred for, among other things, suborning perjury and paying hush money—John Wayne says the country would have survived just fine without the Golden Boy’s intervention: “Name one president who hasn’t lied to the American people.”

John Wesley has outlived most of his Watergate-scandal peers and has not only survived, but has thrived. And he keeps getting the last word, over and over. During his latest PR blitz, he plugged his CNN series and mused about whether Nixon had a conscience (yes, he did, he assures us) in a Zoom interview with the Los Angeles Times from his home in Beverly Hills. That’s where he’s lived since the ’70s, and where he made a career pivot from convicted felon to corporate banker in the ’80s. There will no doubt be more books and op-eds and TV appearances to help further a legacy painting him as a defender of freedom against the evils of corrupt government.

John Wayne, now 74, lives in Hillsboro, a centuries-old town on the far western edge of Loudoun County, where he served for years on the town council. Most of the hot-button issues were typical DC-area, NIMBY-related efforts to ward off rampant development—but only to a point: One of the biggest controversies during his tenure was whether tiny, bucolic and uber-historical Hillsboro should have an HOA-type ordinance or something less stringent. He wrote an ordinance leaning toward the latter which was approved by the town council.

Like many denizens of the other, “unofficial” Washington, John Wayne has spent his whole life in the area, except for his stint in the Army. He counts his legacy in other ways than Hollywood deals and cameos on the cable-news networks. He lives in an old stone house built in 1833 with a fine view of the woods. He has lots of family close by, with two great-grandchildren on the way.

John Wayne doesn’t plan to watch the CNN special, and the books he reads are mostly pre-Watergate historical novels, such as Ken Follett’s series on England from ancient times on. But he does wish that he’d have kept that issue of Time magazine that was sent to him in the summer of ’73. Autographed by an actual John W. Dean—the wrong one, the right one, or otherwise—it could be worth some big bucks on eBay.