A high-profile chef was turned away from sceney Japanese spot Shōtō in DC for her footwear, reigniting a long-running debate over restaurant dress codes.

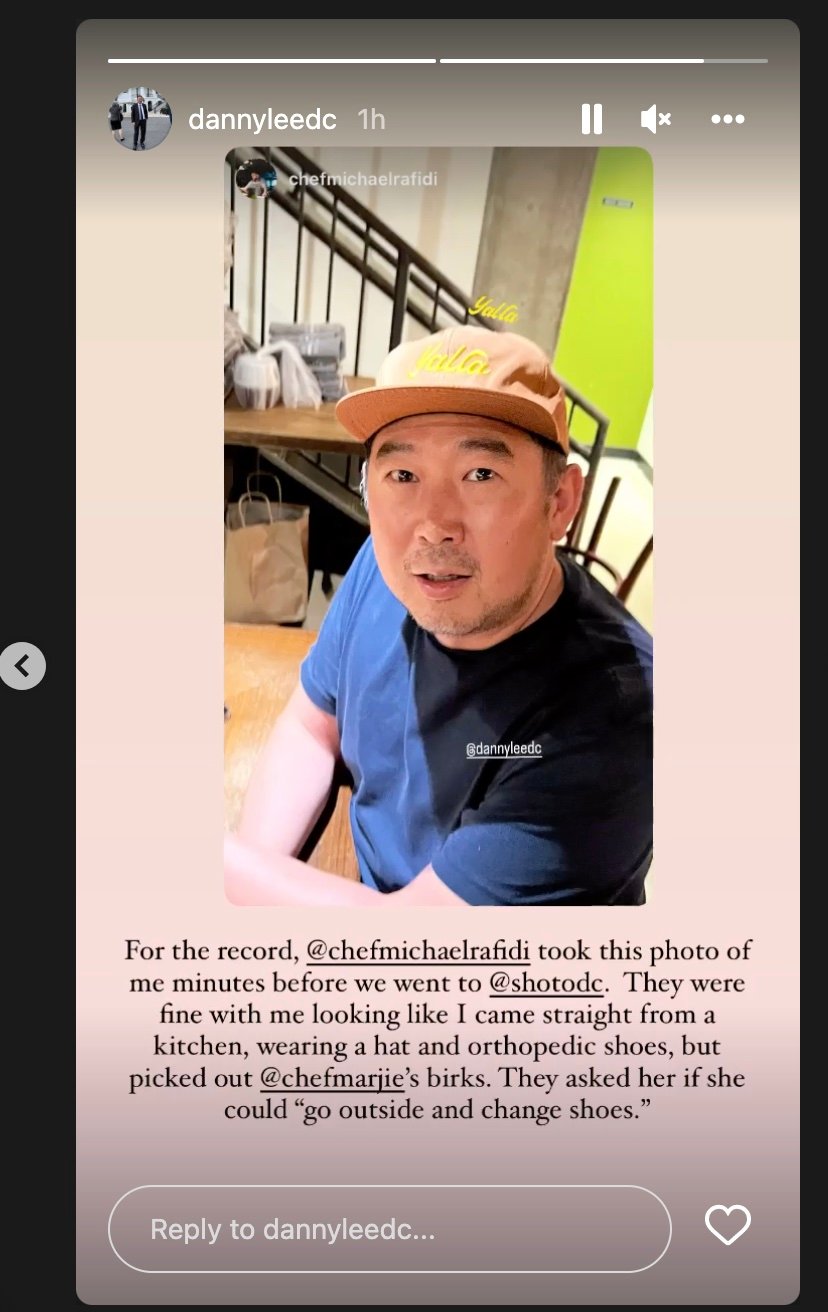

Marjorie Meek-Bradley, a Top Chef finalist who is now a corporate chef for Stephen Starr’s restaurant group (Le Diplomate and St. Anselm in DC, Pastis in New York, among others) dropped into Shōtō near downtown DC on Saturday evening. She arrived with two high profile chef friends, Michael Rafidi (owner of Albi in Navy Yard) and Danny Lee (co-owner of Anju, Mandu, and Chiko). In an Instagram post, Lee says the group—who wanted to get drinks at the bar and didn’t have a reservation—was turned away because of Meek-Bradley’s shoes, which restaurant staff considered “flip flops.” Lee shared an image of Meek-Bradley at the time, wearing a dress and yellow Birkenstocks sandals. He also showed an image of his own attire: a t-shirt, ball cap, and orthopedic shoes.

“They were fine with me looking like I came straight from the kitchen,” says Lee, who declined to comment for the article beyond his social media posts. “But they picked out [Meek-Bradley’s] birks. They asked her if she could ‘go outside and change shoes.’

Shōtō does have an “elegant and smart casual dress code” policy, which representatives say is shared with guests who make reservations in a confirmation email or over the phone. It lays out that “no athletic wear, jerseys, shorts, beachwear, or flip flops are permitted.”

In an email statement to Washingtonian, Shōtō owner Arman Naqi says: “While we understand not every restaurant chooses to enforce our smart casual dress code, we have received overwhelmingly positive feedback from our guests—and many have noted that they are excited to get dressed up in order to celebrate life, friends, family and special occasions (especially coming out of the pandemic).” He adds that guests who are not seated at the time of a dress code infraction are offered “accommodation anytime at their convenience, including the very same day. No matter if they had a reservation or not.”

“It is certainly not to be taken personally, and in total fairness, our team wants to ensure that we are consistent,” Naqi says. “We do not and cannot make exceptions based on who people are—even if they are fellow chefs and restaurateurs that we respect greatly.”

Restaurant dress codes have long been a thorny—and confusing—issue. Shōtō does not have a website where the dress code is displayed for walk-ins such as Meek-Bradley (muddling things further, representatives for the restaurant claim there’s “an imposter” Shōtō website “that someone created” that does not mention dress codes. An official website is expect this fall). And as much as businesses strive for consistency, dress codes can be somewhat subjective. Many would argue that Birkenstocks are not flip-flops—at least not by the dictionary definition—though are they beachwear? More debatable. It’s particularly gray in pandemic times, with the popularity of expensive leisurewear and $76,000 Birkenstocks that still, well, look like Birkenstocks. Meanwhile, why wasn’t Lee called out for his baseball cap?

As the restaurant industry has struggled with inclusion and diversity, some view dress codes as an outdated and problematic practice. A number of businesses have come under fire for enacting or enforcing dress codes that are deemed discriminatory, such as Baltimore-based Atlas Group. In two separate incidents, the hospitality group was accused of having a racist dress code at seafood venture Choptank. Later, the Baltimore City Council adopted a resolution directing Atlas to drop its dress codes after an incident where a Black woman and her son were denied entry to swanky harbor spot Ouzo Bay, while a white child—dressed similarly—was seated and dining.

“To be clear, the reason why dress codes are problematic is because it’s impossible to enforce them with any consistency,” Lee wrote in another Instagram post related to Saturday’s incident. “This enables sexist/classist/elitist/racist thought to guide the enforcement of these ‘codes.’

Shōtō is hardly the only upscale restaurant in DC with a dress code, though standards, specifics, and language vary widely. Stalwart steakhouse The Prime Rib still requires jackets for male patrons, per OpenTable. Meanwhile two-Michelin star Pineapple and Pearls, emphasizes on its website: “We do not have a dress code. But…if we did, it would be fancy. Something along the lines of emerald green tuxedo dinner jackets and gold sequin dresses (or your best New Year’s Eve outfit).” Some are more specific. Park on 14th lays out its dress code in detail, down to how clothes should smell:

“We consider hats, some athletic wear, extremely provocative, tattered or poorly maintained clothing, too informal for the dining experience we provide,” says the business website. “Guests that arrive in t-shirts may not be allowed access into the venue…Clothing emitting offensive odors is not permitted to be worn anywhere on the property.”

In his statement to Washingtonian, Shōtō’s Naqi says he “appreciates and welcomes constructive criticism,” regarding dress codes. “However, and especially between local industry people, I was disheartened to see the way they chose to address this on social media.”

“In her role as the Corporate Chef of Starr Restaurants, I truly hope Chef Marjorie appreciates that I personally have had to make a conscious effort to dress in elegant attire on many occasions at her and Stephen’s restaurants such as Le Coucou,” he says. “I would welcome any future opportunity to host Chef Marjorie, Chef Danny, and Chef Michael, and apologize personally if they were offended by our policy.”

Meek-Bradley was not available for comment at the time of this story.