Vaccines are having a major moment in the news. But Covid and monkeypox aren’t the only conditions for which scientists are developing immunizations.

There are quiet rumblings at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, where researchers are about a year into the first phase of a study aimed at creating a vaccine to prevent one of the most lethal forms of breast cancer, known as TNBC—short for triple-negative breast cancer.

“We are hopeful that this research will lead to more advanced trials to determine the effectiveness of the vaccine against this highly aggressive type of breast cancer,” says Dr. G. Thomas Budd, the principal investigator. “Long term, we are hoping that this can be a true preventive vaccine that would be administered to healthy women to prevent them from developing triple-negative breast cancer, the form of breast cancer for which we have the least effective treatments.”

The Cleveland Clinic is not alone in its optimism. Nearly 20 trials are currently underway all over the country to evaluate the role of vaccines for TNBC.

A vaccine against breast cancer? It’s not as far-fetched as it sounds.

The Road to a Vaccine for Breast Cancer

Triple-negative breast cancer isn’t fueled by hormones like estrogen-receptor-positive and progesterone-receptor-positive breast cancers. TNBC can be hard to treat because it doesn’t respond to hormonal-therapy medicines, as do some other cancers. But that distinction makes TNBC a potential vaccine target.

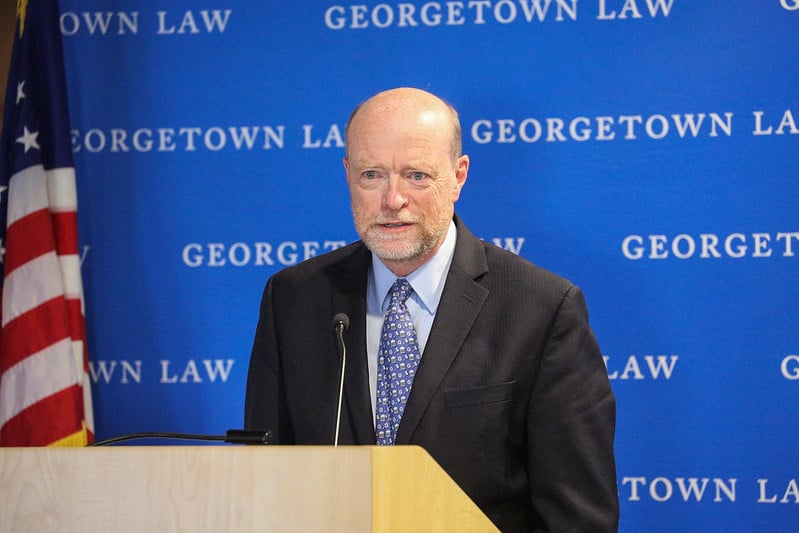

“We have new data showing that when we add immunotherapy to chemotherapy in women with localized TNBC, we increase the chance for cure,” says Dr. Claudine Isaacs, codirector of the Breast Cancer Program at the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center at Georgetown University.

Because the immune system is the mechanism through which vaccines work, a cancer that responds to immunotherapy might respond to a vaccine.

It has worked for other types of cancers. According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology, two types of cancer-prevention vaccines have been approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration—the HPV vaccine to prevent cervical cancer and the hepatitis B vaccine to prevent liver cancer.

“But vaccines against cancer are more complicated than making a vaccine against a virus like Covid,” says Isaacs. “Unlike viruses, cancer is not as uniform, so it is more challenging to identify a single protein that is expressed in all the cancer cells and could serve as the target of the vaccine.”

The vaccine’s aim is to target a lactation protein called a-lactalbumin, found in breast tissue in the majority of TNBC cases. Jump-starting the immune system against this protein could provide immunity against tumors with a-lactalbumin.

In its phase 1 trial, the Cleveland Clinic’s main goal is to find out the maximum tolerated dose of the vaccine for people with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer. If all goes well, subsequent trials would test it in women who are at high risk for TNBC but have not yet developed breast cancer. Phase 1 of the study isn’t slated for completion until at least spring 2023.

Complexities of a Clinical Trial

“A vaccine that targets triple-negative breast cancer was one of the innovations I could only dream of when I started my work as a breast-cancer advocate 40 years ago,” says Nancy G. Brinker, who founded the Susan G. Komen organization in honor of her sister, Suzy Komen.

Despite representing only about 12 to 15 percent of all breast cancers, TNBC accounts for a disproportionately high percentage of breast-cancer recurrence and death. TNBC is also more than twice as likely to occur in Black women and makes up about 70 percent of the breast tumors that occur in women with mutations in the BRCA1 gene.

Brinker’s latest endeavor, Promise Fund of Florida, focuses on addressing the disparities that underserved women face when trying to obtain breast- or cervical-cancer resources and care.

“While this vaccine is a huge advancement in breast-cancer treatment, we must ensure that within its clinical trials there is a diverse representation of women,” she says.

This couldn’t be truer than in DC, where Black women have a breast-cancer mortality rate—33.2 deaths per 100,000—two times higher than white women’s.

“Yesterday’s trials become today’s standard of care,” says Isaacs. “Our goal is to get to the point where we can individualize our treatments so we are treating each patient in a unique fashion—with the treatments that will benefit her and avoid the ones that will not work.”

Interested in participating in a clinical trial? Visit the National Institutes of Health website and search for clinical trials for steps and resources.

This article appears in the October 2022 issue of Washingtonian.