Jason Van Tatenhove was in the living room of his Colorado home on January 6, 2021, when he first saw images of the mob attack on the US Capitol. “Oh, shit,” he thought. “They fucking did it.”

In the more than three years since he’d walked away from the Oath Keepers, Van Tatenhove had come to regard one of the country’s largest anti-government militias as more of a blundering nuisance than a danger to American democracy. Despite their conspiracy-addled fanaticism and heavily armed adherents, he had witnessed group members embarrass themselves at public events from Nevada to Kentucky. But as he watched pro-Trump extremists overrun the Capitol in a rampage that left five people dead—and that a DC jury concluded was effectuated with the help of his former Oath Keeper confederates—Van Tatenhove didn’t just puzzle over his miscalculation. He confronted his own culpability.

“I may have been a part of making this happen,” he told his wife.

A punk-rock bohemian with face tattoos who identifies as bisexual, Van Tatenhove was an unlikely convert. He first connected with the Oath Keepers as an independent journalist looking to write a book. Yet less than two years later, he was participating in paramilitary exercises in the mountains of Montana, traveling to armed standoffs with federal agents, and helping develop the group’s propaganda efforts. “I drank the Kool-Aid,” he says, “and I became more radicalized over time.”

After leaving the Oath Keepers in early 2017, Van Tatenhove was eager to put the experience behind him. He was ashamed. But in the aftermath of January 6, as Washington grappled with the cultural and political forces that had led to the attack, Van Tatenhove began speaking out. He has been interviewed by journalists from as far away as Japan, offered insights to federal authorities and state attorneys general, and appeared in a political ad aiming to keep a self-proclaimed Oath Keeper out of office in Arizona. Testifying before the House Select Committee investigating the January 6 attack last July, he called the group a “dangerous militia” that pursues its objectives “through lies, through deceit, through intimidation, and through the perpetration of violence.”

It’s unusual for a former militia insider to criticize his onetime comrades so publicly, says Rachel Carroll Rivas, who tracks anti-government extremist organizations for the Southern Poverty Law Center. But Van Tatenhove, a 48-year-old father of three, feels compelled to make amends for the damage he’s done. And by sharing his journey of radicalization and redemption, he hopes to prevent others from repeating his mistakes. “Maybe,” he says, “I can help someone decide, ‘You know what? I’m okay without joining a militia. I’m okay without participating in this crazy rhetoric.’ ”

Van Tatenhove first traveled to Eureka, Montana, where a number of Oath Keepers lived, in the summer of 2015. Along with his wife, Shilo, and their two children, he’d been invited on the militia equivalent of a recruiting visit: a weekend trip to the wilderness community to check out potential houses, get better acquainted with the group’s leaders, and determine if he was ready for a career in anti-government extremism.

Founded in 2009 by Stewart Rhodes, a Yale Law graduate who briefly served as a US Army paratrooper and worked as an aide to Republican congressman Ron Paul, the Oath Keepers claim to have tens of thousands of dues-paying members, while outside researchers estimate that the number is between 1,000 and 5,000. An Anti-Defamation League analysis of leaked purported Oath Keeper membership lists found that many are current and former military personnel, police officers, and first responders, all of whom have sworn an oath to “support and defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic.” Described as a “paramilitary organization” by the FBI and as an extremist group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Oath Keepers have a radically libertarian interpretation of the Constitution, and they instruct their followers not to obey legal directives that violate this interpretation—such as orders to disarm.

In late November, Rhodes and another Oath Keepers leader were convicted of seditious conspiracy and other charges related to the attack on the Capitol. Over the course of an eight-week trial, federal prosecutors presented evidence that Rhodes and his allies had spent the run-up to January 6 plotting to forcefully prevent Joe Biden from assuming the presidency—going so far as to stash firearms just outside of DC in a Virginia hotel, where “quick reaction force” teams remained on alert as other Oath Keepers members stormed the Capitol. The jury found three other members of the militia group guilty of other charges linked to January 6, and an additional three Oath Keepers have previously pleaded guilty to seditious conspiracy. As punishment, Rhodes could spend up to six decades in prison.

“The Oath Keepers represent everything that is dangerous about the anti-government militia movement,” says the SPLC’s Carroll Rivas. “They are manipulative, they are coded in their language, they are wrapped in a flag, and they spread these very harmful ideas that are incredibly difficult to counter once they’ve been fully absorbed.”

Arriving at Rhodes’s family compound for a meet-and-greet barbecue, Van Tatenhove saw a tiny barrel-shaped cabin in a dense forest of pine trees. There was a bustle of chickens, dogs, and goats, and a scrum of children running barefoot. To Van Tatenhove, it looked like a back-to-earth hippie community—except, of course, that all of the men were carrying guns.

“Are you sure about this, Jason?” Shilo asked.

A mix of unrealized dreams and mundane pressure had brought Van Tatenhove to Rhodes’s door. An art-school dropout who’d struggled with heroin addiction, Van Tatenhove had secured his first toehold on financial stability a few years earlier, when he’d opened a tattoo shop in Fort Collins, Colorado. By 2013, the shop was busy enough to fill 3,000 square feet of retail space, employ a full-time medical director, and provide a modest life for his family.

Still, Van Tatenhove felt something was missing. The grandson of Jacob Tolkach, an abstract-expressionist sculptor in 1950s New York City, Van Tatenhove had grown up meeting cultural giants such as Andy Warhol and become an accomplished painter himself, holding his first solo museum show at age 24. He longed to pursue wonder and self-fulfillment, even through bouts of drug abuse and poverty, and worried that the relative comfort of his life in Colorado would lead him back to addiction. When his daughter from a prior relationship turned 18, he felt discharged from his obligation to her and ready to chase new adventures.

“Fuck it,” Van Tatenhove recalls thinking. “Let’s go move to the mountains.”

In 2014, he sold his shop, packed up a U-Haul, and relocated with Shilo and their children to Butte, Montana. Van Tatenhove had always wanted to live in the mountains, and he hoped to reestablish a relationship with his estranged father, who lived near Butte.

It didn’t take long to realize that things weren’t working out. He wasn’t able to reconnect with his father in the way he’d hoped, and his plans to open a new tattoo shop fell through. He had no job and few friends, and he felt stranded in an unknown city. “I remember just spinning my wheels going, ‘What do I do next?’ ” he says. “I just kind of was lost.”

During this period, Van Tatenhove began listening more frequently to the radio show of Alex Jones, a far-right conspiracy theorist best known for claiming that the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting was a hoax. In one episode, Jones interviewed Rhodes. Over the course of the discussion, the paramilitary leader explained that he was in the process of organizing a convoy of Oath Keepers to head down to Nevada to support a cattle rancher engaged in a standoff with federal authorities.

The rancher, Cliven Bundy, had failed to pay roughly $1 million in grazing fees and fines to the Bureau of Land Management, prompting federal agents to start confiscating his cattle. But in the spring of 2014, armed militants rallied to Bundy’s side and prevented authorities from repossessing additional cattle, even though a court had authorized them to do so. The Oath Keepers, Rhodes explained to Jones, were on their way to provide additional muscle.

Van Tatenhove was captivated. He was skeptical of government power himself, and he saw the Bundy Ranch standoff as principled and exciting. More than that, he viewed the Oath Keepers as a chance to follow in the footsteps of his literary hero, gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson, who lived with an outlaw biker gang to research Hell’s Angels, the 1967 book that jump-started his career. During his twenties, Van Tatenhove had worked for an underground music publication in Denver. What if, he wondered, he could embed with the Oath Keepers and write a book about the experience?

Within a week, the logistics were in place. Van Tatenhove had secured permission from the Oath Keepers to tag along with them to Bundy Ranch, and he’d found an independent news outlet, Revolution Radio, that was willing to air his dispatches as he gathered book material.

“This is a historic event,” he told his wife. “I can make this my Hell’s Angels.”

The Oath Keepers operate under the assumption that at some point in the not-too-distant future, the federal government will execute a secret plan to confiscate people’s firearms, and also force American citizens into concentration camps. Of course, there’s no evidence for this belief, which the SPLC’s Carroll Rivas describes as “the essence of the proper survivalist’s fear.” Nevertheless, it makes the militia fanatical in its support of gun rights, and generally hostile to civil authorities.

These qualities became clear to Van Tatenhove on the very first day he embedded with the Oath Keepers, in April 2014, when he hitched a ride with several members to meet Rhodes in Kalispell, Montana. Along the way, Van Tatenhove recalls, the car stopped at a nondescript office in an ordinary strip mall. In the basement, he says, was a makeshift armory filled with assault-rifle magazines, fixed-blade knives, camouflage jackets, and other tactical gear.

“Take whatever you want,” a person at the office told the men.

After loading up the vehicle, the men continued to Kalispell, picked up Rhodes, and set off for Bundy Ranch. During the nearly 1,000-mile drive from Montana to Nevada, Van Tatenhove began getting to know the militia’s founder. Then in his late forties, Rhodes was a beefy figure in a baseball cap and a black eye patch—the latter the result of an accident three decades earlier, when he dropped a handgun and shot himself in the face. Van Tatenhove found Rhodes to be charming and intelligent, an engaging conversationalist who was well-read in American history.

But Rhodes’s stewardship of the Oath Keepers was plagued by the same sort of bumbling that had left him blind in his left eye. Shortly after arriving in Nevada, Van Tatenhove says, Rhodes and another Oath Keepers official received calls on their cell phones. The message to both men was the same. Then–attorney general Eric Holder, the caller warned, had just authorized a drone strike on Bundy Ranch. The entire area was about to be incinerated.

Everyone in the car was convinced the calls were real, says Van Tatenhove, who immediately called his family to say he loved them. After scrambling to pass along the “intel” to Bundy, Rhodes fled to safety with the rest of his militia. When it all turned out to be a hoax, reports the Southern Poverty Law Center, Bundy’s remaining militants ridiculed the Oath Keepers as delusional and chicken-hearted.

Still, Van Tatenhove was thrilled. He soon began working as an inspector for the Montana Department of Livestock, a full-time job that provided much of his family’s income. But he started spending his free time traveling with the Oath Keepers, filing radio reports about their activities, and building trust with members. In August 2015, he accompanied them to Lincoln, Montana, to report on an armed standoff with the US Forest Service.

While there, Van Tatenhove recalls, a member of the Oath Keepers’ inexperienced media team asked him for help with a press release. Van Tatenhove says he agreed only to assist with formatting, wrote none of the copy, and insisted his name be kept out of it. When the release went out, however, his name was attached.

At 6 the following morning, Van Tatenhove says, he received a call from his boss at the Montana Department of Livestock. “Your name is in every newspaper in the country right now,” his boss explained. “And not in a good way.”

Van Tatenhove resigned from his job. He was furious with the Oath Keepers and called Rhodes to complain. The militia leader, who needed someone with journalism experience, proposed a solution.

“Do you want to come work for us?” Rhodes asked.

Van Tatenhove shared the Oath Keepers’ concerns about government overreach. He says his outlook stemmed from broad federal policies, such as the war on drugs, as well as specific incidents, like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, the notoriously unethical experiment in which the US Public Health Service withheld treatment from Black men infected with the disease. Van Tatenhove also admired the rugged beauty of the eastern Montana timberlands, where many of the militia’s members lived. And he knew that the job’s financial benefits—a decent wage and subsidized housing—would make his family more comfortable than they’d been back in Butte.

But more than all that, Van Tatenhove simply didn’t want his adventure to end. So in the fall of 2015, he and his family moved to a horse ranch in Eureka. As the Oath Keepers’ national media director, he was primarily responsible for developing online propaganda. He began each day by checking the Drudge Report, Fox News, and other right-wing outlets to see what issues were generating the most outrage. “We were looking for angry reactions,” he says, “just anything with [a] heightened emotional state.”

After working with Rhodes to select an appropriate source of animosity—Obamacare one day, gun control the next—Van Tatenhove would post missives to the group’s website. Following a 2015 shooting at Umpqua Community College in Oregon that left nine people dead, for example, he issued a joint statement with Rhodes. The “obvious answer to school shootings on college and high school campuses is that the students must stop submitting and cooperating in their own murders,” the two wrote. “They must fight back, and we will show them how.”

Stoking resentment online, Van Tatenhove was able to amplify the group’s reach. “I’d have articles that I put up in the late evening,” he recalls, “[and] I’d have, like, 120,000 views overnight.”

Though the Oath Keepers’ trip to Bundy Ranch was a debacle, news coverage of the group’s appearance triggered a wave of donations. “I think Bundy Ranch was an eye-opening learning moment for [Rhodes],” Van Tatenhove says. “Because he saw that he could raise $30,000 to $40,000 in a week.”

The group began inserting itself into national controversies. Oath Keepers with assault riles went to Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014 to provide vigilante security for local businesses during the riots that followed the police killing of Michael Brown. A year later, Rhodes and company offered to bring their guns to Kentucky to protect Kim Davis, a county clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples.

In neither case did the Oath Keepers accomplish much; police asked the group to end their unlicensed security activities in Ferguson, and, according to Van Tatenhove, Davis’s family refused to accept its support in Kentucky. Still, these armed publicity stunts helped Rhodes raise the militia’s profile—and his own. “He got a much wider audience,” Van Tatenhove says. “He got much more national attention from the press, which translated to more readers and viewers [on the website], and in the end more donations and memberships.”

Van Tatenhove became something of a body man for Rhodes, fielding phone calls and driving him to rallies and standoffs. During their lengthy car trips, the two became close; eventually, Van Tatenhove felt comfortable enough to tell Rhodes he was bisexual.

Unlike Neo-Nazis and other hate groups, the Oath Keepers have long disavowed outright racism and bigotry—a distinction that, according to the SPLC’s Carroll Rivas, helps it recruit military veterans and law-enforcement officials who consider themselves upstanding members of their communities. According to Van Tatenhove, Rhodes had no problem with his sexuality. To the contrary, he explained that the militia’s back-end merchant-services department was run by a committed gay couple in Las Vegas.

“You know,” Van Tatenhove recalls Rhodes saying, “I wish we could do a standoff to protect a gay couple and their pot farm from [government overreach].”

Every few weeks, Van Tatenhove says, he would travel with Rhodes to remote locations in Montana or Idaho for paramilitary exercises. Over the course of several days, veteran warfighters—“Big Ugly,” one was called—would lead groups of several dozen camouflaged men in everything from ambush training to sniper practice. “There was a certain amount of [training in] first aid and map reading and land-navigation skills,” Van Tatenhove says. “But 95 to 98 percent of it was how to effectively kill people.”

Following the attacks on the Capitol, Van Tatenhove came to view these weekend excursions more ominously. “It wasn’t just fun and games,” he says. “It was paramilitary training for causing violence.” At the time, though, he found them to be empowering and meaningful; as the men hiked through the woods and ate dinner by campfire, they developed an esprit de corps. “There was a deep sense of community,” Van Tatenhove says, crediting a feeling of belonging with helping him remain sober during that period.

“There was a certain amount of [training in] first aid and map reading and land-navigation skills. But 95 to 98 percent of it was how to effectively kill people.”

Over time, that feeling intensified. Van Tatenhove was flying by chopper to anti-government rallies, firing assault rifles at wilderness gun ranges, and backchanneling with reporters from national news outlets. At one point, as part of their research for an upcoming video-game release, a team of Canadian game designers traveled to Van Tatenhove’s ranch in Eureka to see how actual militia members lived.

On the Oath Keepers website, Van Tatenhove was urging readers to carry guns with them at all times and to “man up” by enrolling in martial-arts classes. “You will be prepared to defend yourself and stop these criminals, terrorists, and foreign enemies that have already declared war upon us and attacked our very way of life,” he wrote in a post on the website. “Today is the day we need to show these villains that they truly have just awoken a sleeping giant!” By then, the former punk-rock artist had given up his Mohawk and Ramones T-shirts in favor of hunting apparel and cowboy boots. “I remember looking in the mirror like, ‘Who the fuck have I become?’ ” Van Tatenhove says.

The adventure began to lose its appeal in January 2016, when state police officers shot and killed a militant rancher, Robert “LaVoy” Finicum, during a standoff at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon. Van Tatenhove had been close with Finicum; two days before the shooting, he says, he had begged the 54-year-old by phone to clear out of the refuge.

As Van Tatenhove watched Finicum’s young daughters break down in tears at their father’s funeral, he began to wonder what his continued involvement with the Oath Keepers might mean for his own family. “I got in too deep,” he says. “I was just feeling like I got into this situation that I’d convinced myself was cool and exciting, and now it’s just fucking turning ugly.”

At the same time, Van Tatenhove was growing troubled with what he viewed as the group’s drift toward intolerance. The SPLC’s Carroll Rivas says the Oath Keepers have long trafficked in coded antisemitic tropes—for example, their animating fear of the subjugation of individual freedoms to a tyrannical “New World Order.” Throughout 2016, Van Tatenhove says, he saw Rhodes become increasingly willing to partner with openly racist figures—such as the white nationalist Richard Spencer—whom he wouldn’t have been comfortable associating with in the past. “They were taking a harder-right bent,” Van Tatenhove says. “They were moving into the realm of [outright] racism.”

Van Tatenhove’s concerns crescendoed several months later, he says, when he was at a grocery store in Eureka and overheard a senior Oath Keeper insisting that the Holocaust had never taken place.

“What are you talking about?” Van Tatenhove interjected.

“Well, if it did happen, it was just grossly exaggerated,” the senior Oath Keeper replied. “And the concentration camps we had in America were so much worse.”

“I got in too deep. I was just feeling like I got into this situation that I’d convinced myself was cool and exciting, and now it’s just fucking turning ugly.”

Van Tatenhove now admits that during his affiliation with the group, he may have been blind to its members’ bigotry. “Maybe I didn’t want to see it,” he says. But when he overheard the senior Oath Keeper casually denying the Holocaust in public, he knew his days in the group were over. Van Tatenhove’s aunt and cousin are Jewish; he has fond childhood memories of celebrating Hanukkah and Passover with them. How could he justify being part of a group in which naked antisemitism was tolerated? Van Tatenhove bolted out of the grocery store, drove back to his cabin, and told his wife and children it was time for a change.

“I just was like, ‘Fuck this,’ ” he says.

By late 2017, Van Tatenhove and his family had moved out of their Oath Keepers–subsidized cabin and into another house in Eureka. He no longer regarded Rhodes as a principled warrior-philosopher but rather as a self-aggrandizing huckster. “His ideology really became inserting himself in any national event that could further his exposure, his access to new members, and the inflow of money,” Van Tatenhove says. “It was a huge ego drive.”

Around this time, Van Tatenhove attended a meeting of a Eureka search-and-rescue organization. He was approached by Ronnie Oropeza, a US Forest Service police officer who was familiar with Van Tatenhove through his work tracking local extremist groups.

“I know you work for the Oath Keepers,” Oropeza said. “Can you tell me why you’re here?”

Van Tatenhove explained that he wanted to help the community.

“I really hope that that’s true,” Oropeza replied.

Attempting to atone for his time in the Oath Keepers, Van Tatenhove soon joined the search-and-rescue association, obtained an EMT license, and became certified to fight forest fires. Through this work, he developed friendships with the first responders and law-enforcement officials whom he’d once considered the enemy. “It was just such an amazing experience to see the camaraderie and the brotherhood of being up on a mountain [fighting fires] for 14 days,” he says.

Van Tatenhove grew particularly close with Oropeza—so close that when Oropeza was called one night to a work emergency at around 11 pm, he asked Van Tatenhove to care for his young children. “He came and got my kids,” Oropeza says. “And I knew that they were safe.”

But just when Van Tatenhove felt he’d managed to put the Oath Keepers behind him, he says Rhodes appeared at his door. Rhodes’s wife, Van Tatenhove says, had kicked him out and left him no place to go. “Can I stay for a few nights?” Van Tatenhove recalls Rhodes asking.

For the next eight months, the head of one of America’s largest militias became the Van Tatenhove family’s roommate from hell. Jason, his wife, and their 16-year-old daughter, Lux, all recall Rhodes spending most of his time in their basement, typing into a laptop while wearing boxer shorts and a stained sleeveless shirt. “I’ve seen that man in his underwear,” Lux says.

Upstairs, Van Tatenhove recalls, Rhodes spilled food, sullied the microwave, and refused to clean up after himself. “He would annihilate the kitchen,” says Shilo. The family would often wonder where all their plates and silverware had gone, only to find their cutlery—now crusted and moldy—in Rhodes’s car. It looked “like a fucking science experiment,” Van Tatenhove says.

Eventually, Van Tatenhove says, he told Rhodes it was time to leave. Shortly thereafter, Van Tatenhove moved his family back to Colorado, where he began trying to reclaim his artistic identity. He put his hair back into a Mohawk and found work as a freelance reporter for a local newspaper. For his first assignment, he covered a local Black Lives Matter protest.

Meanwhile, the Oath Keepers were undergoing their own transition. Back in 2016, Van Tatenhove says, Rhodes was so unmoved by Trump that he wouldn’t have voted in that year’s election had Van Tatenhove not driven Rhodes to a polling station and encouraged him to cast his ballot for the former reality-TV star. But once Trump took office, Van Tatenhove says, Rhodes came to see the 45th President as a “vehicle to realizing these fantasies of being a paramilitary leader in a dystopian America.” The Oath Keepers subsequently served as armed security guards at Trump’s rallies, showed up at a “We Build the Wall” event, and spread false claims that Biden had stolen the 2020 election—ultimately urging Trump to maintain control of the federal government by invoking the Insurrection Act.

“It is CRITICAL,” Rhodes said on the militia’s website on January 4, 2021, “that all patriots who can be in D.C. get to D.C. to stand tall in support of President Trump’s fight to defeat the enemies foreign and domestic who are attempting a coup, through the massive voter fraud and related attacks on our Republic.”

By then, Van Tatenhove was completely done with the Oath Keepers. “I wanted to kind of hide,” he says. But when he saw his former allies marching in “stack” formation up the east steps of the Capitol, he knew that wasn’t tenable. “I felt I needed to speak out,” he says.

Last July, a dark SUV carrying Van Tatenhove and his pro bono lawyer, Raphael Prober of Akin Gump, passed through a security checkpoint and entered the US Capitol complex. Inside, Van Tatenhove was led up a spiral staircase and into a waiting room. Roughly 15 minutes before it was time to address the January 6 committee, he recalls, three Capitol Police officers accompanied him to the bathroom.

“Thank you for what you are doing,” one of the officers said.

Van Tatenhove choked up. “No, thank you,” he replied. “You were the ones that paid the real cost of what had happened that day.”

Walking into the hearing room where he would sound an alarm about the ongoing threat that groups like the Oath Keepers pose to the country, Van Tatenhove spotted Michael Fanone, the former DC police officer who was nearly beaten to death by the mob. Some of the other witnesses approached Fanone to say hello. But Van Tatenhove kept his distance. He felt it wasn’t appropriate to introduce himself.

“I mean, I wasn’t there, I didn’t storm [the Capitol],” he says. “But some of my messaging rhetoric fucking played a part in that guy almost losing his life.”

In the aftermath of the attacks, Van Tatenhove began speaking on the record with the media about the inner workings of the Oath Keepers. Connecting with Mary McCord of Georgetown University Law Center’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection, he found himself meeting with prosecutors and law-enforcement officials around the country who were looking to safeguard their communities. He wrote a book, The Perils of Extremism, to be published by Skyhorse Publishing in February.

By sharing his story, Van Tatenhove hopes to make amends. He also hopes he can help de-radicalize others who have fallen down the extremist rabbit hole—people, he told the January 6 committee, who are being “used as pawns in a dishonest campaign to capture more money, influence, and power.” “It’s important to show my kids, like, when you fuck up, try to make it right,” he says.

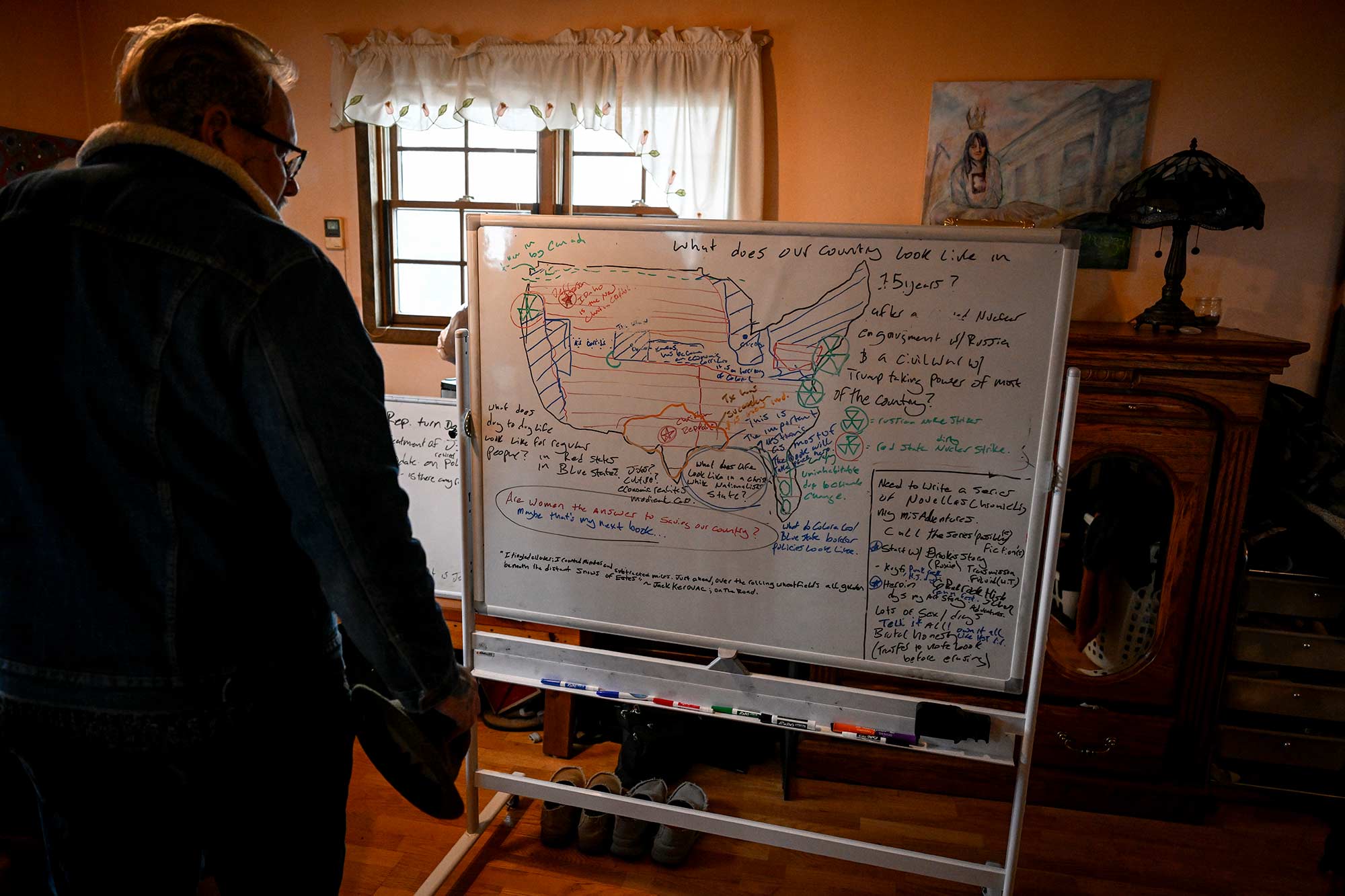

Back home in Colorado, Van Tatenhove is now writing a novel about a future America that has descended into civil war. The story traces a daughter’s efforts to rescue her father, who’s been imprisoned in a Trump-controlled region on false charges of seditious conspiracy. The book is fictional, a way for Van Tatenhove to reconnect with his artistic side. It is also a warning. “I most likely did play a part in bringing our country to where it is now,” he says. “With that realization, it’s just like, ‘Well, shit, I’ve got to try to fix this a little bit if I can.’ ”

This article appears in the January 2023 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)