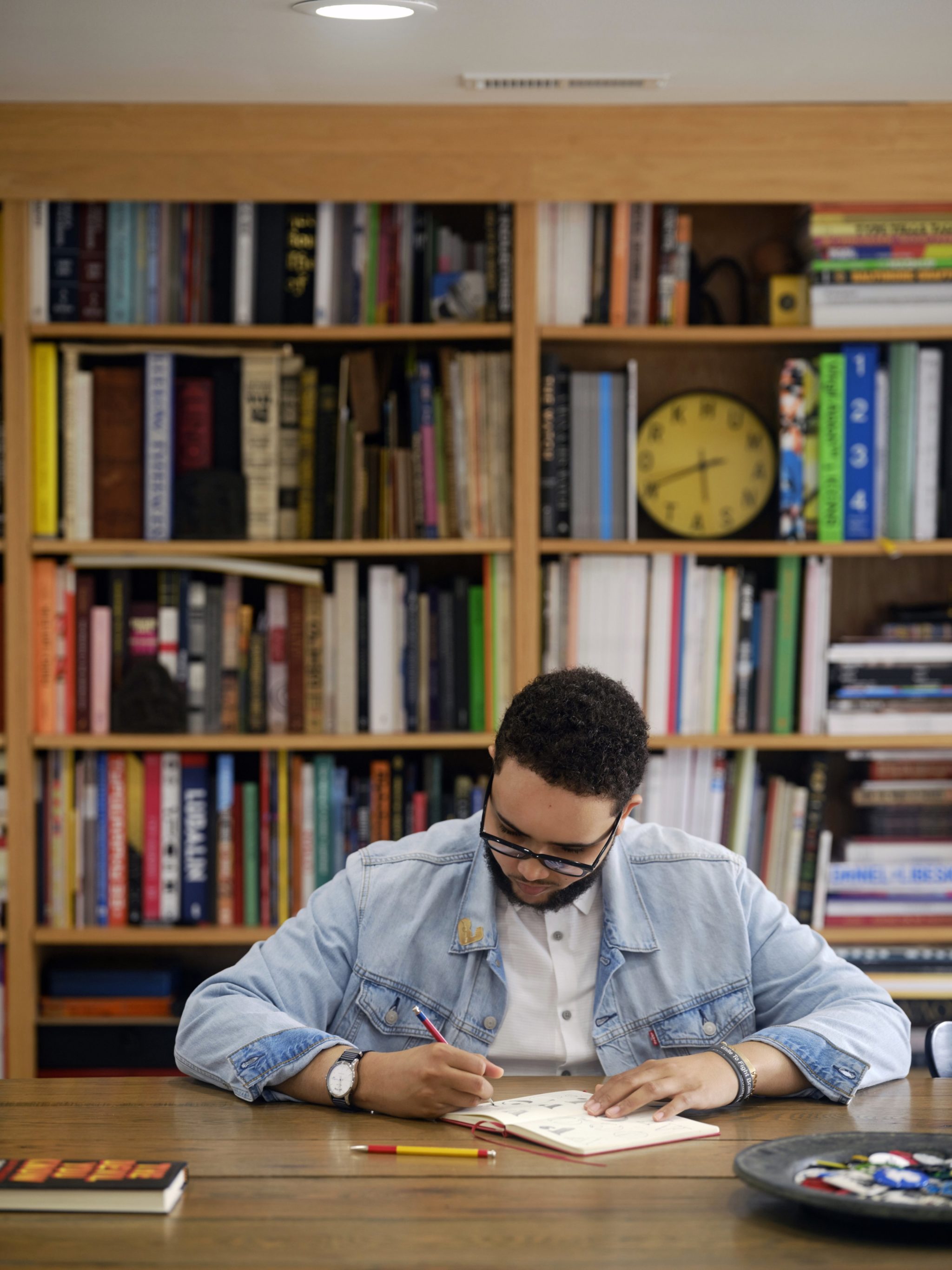

Tré Seals plans to ease the world out of its Helvetica obsession one font at a time. After becoming frustrated by the monotony of the graphic design industry, he started his own foundry, Vocal Type, which he runs out of a refurbished stable on his family’s farm in Accokeek. Instead of focusing solely on aesthetics, Seals creates his typefaces based on significant moments in Black history and culture.

Vocal Type launched in 2016 as Seals’s side gig, and his work gained popularity after the murder of George Floyd, when the design industry started making more of an effort to seek out Black creatives. Since then, it’s grown into a full-time operation, and his typefaces have been tapped for Black Lives Matter murals, Spike Lee’s recent monograph, and the Amazon Labor Union logo. Last November, he even snagged a spot on Forbes’ 30 Under 30 list. But being one of the few African-American type designers in the world isn’t easy.

Washingtonian: What drew you to type design?

Tré Seals: At the age of four, I was diagnosed with a brain tumor, and balancing between drawing and lettering became somewhat of a meditative practice for me. It continued even when the tumor was gone as a means of sharing what I was going through without having to verbally express it. Then I was diagnosed with a residual brain tumor in 2002 and everything changed. I just cared a lot more about everything I did, whether that was drawing or writing. Instead of drawing the things that I used to, like skateboarders and basketball players, I was drawing classical art. After starting my first business in the fifth grade, I started exploring lettering in different areas. By the time I was in the 12th grade, I’d already started designing my first font. I had no clue what I was doing, but I loved it. Because of all this exploration in type, I already had a sense of what I liked and didn’t like by the time I got to college. At the same time, I fell in love with branding and creating brand identities and that love for type really came in handy. But all of a sudden, I found out that designing fonts and branding didn’t have to be these two separate things.

But, at the same time, I saw this lack of diversity in the places where I was working. I was usually either the only person of color, and I just got bored because it was like everything I saw all looked the same, no matter how beautiful it was. I realized that it was because of this lack of diversity in people, the work that was being created, and the sources of inspiration. That’s what inspired Vocal Type.

Are you mostly self-taught or did you take type-design classes?

I would say I’m 80 percent self-taught, especially when it comes to designing fonts. Most of it is a lot of trial and error, and I took an online class that basically taught me how to use the professional program that most font designers use today. That’s pretty much what got me where I am. It taught me how to analyze other people’s work to see how they design certain letters, and that kind of influenced my work.

Your typefaces tend to have an important story behind them. Is that intentional?

It’s much more of an intentional process. The starting point is always different, but the end result is pretty much always the same. Let’s say I want to make a typeface inspired by a specific movement. I’ll start researching that movement, and from there, I’ll look to different events that were pivotal within that movement. Then, I’ll start looking for type, whether that be banners or protest signs from that event and movement. Once I have the type, I’ll try to identify an activist that’s tied to both the event and the movement to name the font after so it all ties together. One thing that I always try to do is pick something that multiple people have a connection to, so you’ll never see me make a font inspired by one protest sign that one person made and one person carried. It’s always a protest sign that 100 people carried with the same message or it might be a banner that 10 people carried to reinforce this idea of unity, but the starting point can always be different and still lead to the same result.

While your designs are bold and striking, they are also very legible. Is accessibility something you work towards in your fonts?

Most definitely. I feel like everything happens for a reason, so every design decision should have a reason behind it. This is how I work, in general. All types should really be treated that way, whether it be just the design of the letters or the story behind them. Design and type should be inclusive. It shouldn’t discriminate. One of the fonts you may have seen, called VTC Ruby, was previously named Jim Crow, which has a whole problematic history to it. People so often say that words have power, but I feel like the letters that make them should also have power.

What’s your goal within the type design industry?

There’s this thing called stereo-typography, and the font design is based on the stereotype of a certain culture. If you think of the lettering style that you see on so many East Asian restaurants, they’re called “chop suey” fonts because it’s a stereotype of East Asian culture. I feel like that’s one of the things that I’m really fighting against, because stereotyping basically just has no real reference or understanding of the culture and doesn’t honor the culture anyway. It’s more of a dishonor. My hope is to really change that and just make a more intentional and thoughtful design industry as a whole and just inspire people to make more meaningful work.

While your work has become increasingly popular, not many people know the face behind the art. How do you feel about that?

You actually do not have to give me credit for using my fonts, but I find that there are a lot of people who do and I’m grateful for that. I feel like a lot of my business comes from people letting others know that this type was made by a Black type designer and there’s an intentional history and story behind it. These aren’t just letters that mean nothing…that add nothing to the story. I think there are a lot of people who are simply proud to know that there is someone who is making type that honors their culture.

Do you think that’s fair?

I think it’s fair. I don’t feel any particular way of whether or not someone does or doesn’t credit me for using my type. First of all, there are so few type designers in the world that it’s pretty much assumed now that whoever designed a logo, a book cover, or a poster did not design the type for those projects. I think there are only a little over 200 people in the world I’ve heard that actually design type for a living, so I’m not sure credit is needed.

What has been the biggest obstacle in your career as a rare Black type designer?

It’s just been the learning curves. Education is not very accessible, and I feel like that’s been used as a means of controlling who can and cannot enter the industry. There are more types of designers who are working on expanding access to type design education. But prior to that, the only way to learn type design was either to get into a master’s design program and only take it for two semesters, move to New York or California to take in-person type design classes, or move to Europe to take type design classes. Outside of that, there is no real type design education in America. I feel like that has been the greatest obstacle for me. I still feel like I don’t know everything or as much as I should at this point.

Many people have some interesting hot takes on fonts. Are there any fonts that you think have a bad rap, but deserve better?

I feel like Helvetica gets a bad rap. I do have beef with it, but I think I just don’t like how overused it is. It isn’t that I don’t like the design. I just think it’s one of those things that’s so overused that it doesn’t represent anything or anyone at this point.

So you think Helvetica’s overrated, but it still deserves better?

Yeah, from a branding perspective. Brand identity is supposed to help people identify you and your brand from other brands, right? But, there are so many brands in the world who are only using Helvetica so that they don’t offend anyone and it kind of attracts everyone. I think Target uses it. They just had a custom version where the dot on the eye was round instead of square. Tom Ford, Off White, pretty much every brand in the world, whether it’s luxury or inexpensive, uses Helvetica as their brand, typeface or logo. And, I feel like that’s kind of getting into this world, where personality doesn’t have a place. [Helvetica] has a place more so on the New York subway signage or road signage…the ubiquitous things that need to be super legible and don’t need to have personality. But from a branding perspective, I feel like that gets into dangerous territory.

Do you have a dream project?

Unfortunately, this can’t happen anymore. My dream client was Virgil Abloh [the influential designer who died in 2021], and I had this idea for either making a custom typeface for Off White, or using a typeface I released earlier this year called Harriet. This dingbat font was inspired by quilts from the Underground Railroad, and I just envisioned them being used alongside the checkered pattern from Louis Vuitton. That was one of my dream projects, but now I’m not really sure what my dream project is outside of growing Vocal Type, to be honest.

What’s the game plan for growing Vocal Type?

Part of it is to eventually launch Vocal Type Studio, like a graphic design practice. Aside from custom typefaces, I’ve designed a book for Spike Lee and Jamie Hendricks. So far, I’ve published my own book called Dream in Color. I designed the logo for Stacey Abrams’ campaign and a lot of non-font design projects. I’m still using my fonts, but those design projects would be a perfect fit for launching Vocal Type Studio sometime down the road.

This interview has been edited and condensed.