Many of us have beloved recipes—but only a few have created a dish so good they’ll take it to the grave. Rosie Grant began exploring the delicious side of death after she discovered a cookie recipe engraved on a New York tombstone. At the time, she was completing a master’s at the University of Maryland and interning at Capitol Hill’s historic Congressional Cemetery. (The afterlife is a family trade—her parents are ghost-and-graveyard-tour operators at Alexandria Colonial Tours.) What started as a grad-school social-media project documenting cemetery life on TikTok spiraled into a viral platform, @GhostlyArchive, where Grant recreates tombstone recipes from across the US—cookies, fudge, even the occasional party dip. We chatted with Grant, now a librarian and communications specialist, about the history of gravestone recipes and why cookies make a good memorial.

@ghostlyarchive 4 more recipes #gravestonerecipe #recipegravestone #cookingfromscratch #bakersoftiktok #gravetok #cemeterytok #recipesoftiktok #recipes ♬ Flowers – Miley Cyrus

What’s the origin of gravestone recipes?

The oldest I’ve come across is from 1994. It’s modern gravestones that are very personalized with hobbies, pets, favorite quotes. If you go to Congressional Cemetery, a lot of the modern graves have interesting memorabilia. There’s the famous “gay corner,” which was created during the AIDS epidemic. Some cemeteries would not bury a person if they died of AIDS or were openly gay—Congressional would. Leonard Matlovich, an activist, was buried there—he started the gay corner. Now all these other people who are in this field of activism are buried there. [A memorial to Frank Kameny] says “Gay is good.” [J. Edgar] Hoover, the former FBI director, is a few plots over, and he had a lot of harmful [anti-LGBTQ] policies. So they picked this area to be near him as a “screw you” kind of thing.

Have you discovered any gravestone recipes in DC?

The closest I’ve found is in New York. Almost all are from women. There’s one woman in Arkansas—still alive—who put up her gravestone when her husband died. She put her sugar-cookie recipe on her stone. Her husband had put together his [stone] and the things that he was really proud of, and she’s like, “I’m really proud of this recipe. People know me for it. When I sent my kids to school with these cookies, teachers would ask for the recipe.” It was a way that she wanted to be remembered.

Why do you think gravestone recipes are more popular with women?

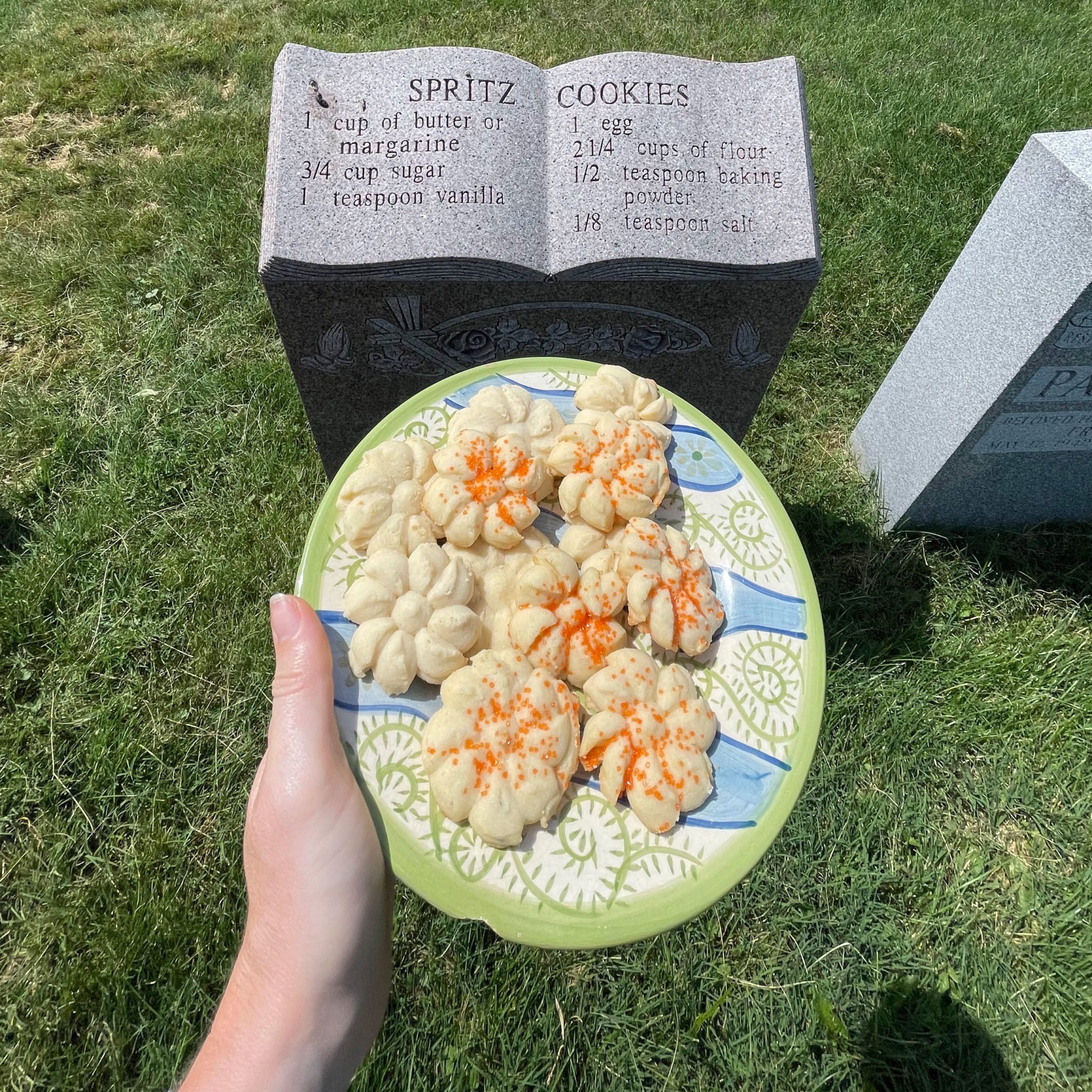

I think most of these women lived “normal lives.” They loved their families. They loved hosting people. It was a skill set that they were really proud of. The first recipe that I made was a spritz cookie from the grave of Naomi Odessa Miller Dawson. She is a woman buried in Brooklyn, New York, at Greenwood Cemetery. Talking to her family, she had a lot of amazing qualities. But she was a really good cook, and food was essential to her life. It’s the same reading the obituaries of a lot of other women who weren’t necessarily famous in their lifetimes, but they were known in their communities. And they just seemed like very fun, lively people.

What kind of recipes have you discovered?

A lot have been cookies. There’s something forgiving about a cookie recipe. You can throw it all together. The instructions can be minimal—they’re limited on a gravestone—and it involves standard ingredients: butter, sugar, eggs.

Where is the Ghostly Archive project going in the future?

I have 20 recipes so far. Not everyone is on social media, so if there’s a way to make the recipes more accessible—a book or website—it could be a nice resource. I’ve also been learning more about funeral foods. Last week I made a Texas sheet cake, which is a very popular funeral food: it’s sweet, it feeds a lot of people, it’s very comforting and easy to make. I also made funeral potatoes. They’re like cheesy potatoes with corn flakes or crackers crumbled on top. Same thing. Very comforting.

There is a strong tie between food and death, and the rituals. What are some surprising things you’ve discovered about the connection?

Have you seen Ratatouille? I always think about that scene at the end where the villain is eating a dish that he had from childhood [and it transports him back]. Both of my grandmothers died during the pandemic. One would make the same yellow cake with chocolate icing for all of our birthdays—I’m one of 32 grandkids, Irish Catholic—and she would make it every year. That was your birthday marker. If I eat that yellow box cake, I remember sitting with her at the table at my eighth birthday party. I can smell the things that I smelled, and taste the food, and all of my senses are wrapped into this. Going back to a person putting a recipe on their gravestone—what a gift to your family member. It’s not just saying their name or trying to picture their face. It’s like you are dropped into the memory of them.

Do you think by showcasing the recipes, you’ll encourage more people to do them?

I believe so. Even if there aren’t more people putting recipes on gravestones, there are more conversations about how people want to be buried. It’s something that we all have to deal with at some point. There’s something called the Death Positive Movement, which is this idea that people—and society—are better off if you think about your mortality and how you want to be celebrated. Death is a collective human experience. And it’s been so much in our consciousness over the last three years, in a way that I was uncomfortable with, which is why the recipes are nice. I don’t want to think about my own death, but I don’t mind thinking about a recipe people remember me for.

What would that recipe be?

Probably clam linguine.

One of your early Ghostly Archive posts details five surprising things you learned on your first day at Congressional. What was the biggest lesson overall?

I wasn’t aware of the importance of community connection. A lot of cemeteries are at risk—particularly around DC. We’ve lost several minority cemeteries that were bulldozed or repurposed. There’s a famous one in Laurel, Maryland that turned into a parking lot. So the more a cemetery is connected to its community, the better for the health of the cemetery itself. Some of the comments I’ve gotten [on social media] are like, “I think it’s so weird that you go into cemeteries. You must get haunted.” That’s actually bad for the cemetery’s survival. Something that Congressional does really well is that it’s very connected to the community— its volunteers and famous dog-walking program have allowed the cemetery to exist in a very healthy way. They have an archivist. They can pay for a preservation team. Their motto is very much about liveliness, and continuing to bring in visitors. It’s very much for both the living and the dead.

Do you have other favorite cemeteries or gravestones around DC?

One of my favorites is Evelyn B. Davis. She was a media mogul, and she’s buried in Rock Creek Park Cemetery. She has two gravestones. One of them lists her [four] ex-husbands. On the second stone, she has her work resume. And then on her actual tomb it says “Queen of the Corporate Jungle.”

This article appears in the April 2023 issue of Washingtonian.