Contents

On a chilly morning in early March, the most globally famous Washingtonian who has never worked out of the Oval Office mills about the DC United players’ lounge, making his espresso and greeting players as they trickle in. He wears a team-issued tracksuit, a baseball cap, and slides. His voice—seldom soft on the field—never rises above a mumble. A soccer deity, he mingles with mortals who still can’t quite believe he walks among them.

What is Wayne Rooney doing here?

Possibly the greatest English player ever, Rooney retired as the all-time leading scorer for both England’s national team and Manchester United of the English Premier League, the most storied club in the planet’s most popular sports league. Near the end of his laureled career, he joined DC United for one and a half seasons and dragged the franchise to the Major League Soccer playoffs—twice.

Now 37 years old, Rooney is working to return to the Premier League as a coach. Surprisingly, his path runs through this practice facility in one of the last stretches of undeveloped land past Dulles Airport, at the end of a winding road that’s only partially paved. Vibes-wise, it’s about as far as you can get from the sideline at Old Trafford, Man U’s fabled stadium. There’s little glitz, and even less of the relentless attention that has long shadowed Rooney like a dogged defender.

Only that suits him fine. When Rooney became DC United’s head coach last summer, he took on a former dynasty fallen on hard times, sporting a losing record and a roster with a lot of young talent plucked from its youth academy. It was a deliberate choice, and not the kind that yields quick wins and a glide path to a bigger job.

“I’m still a young coach and want to learn as much as I can,” Rooney says. “It’s no secret—I want to manage at the top level in the Premier League. That’s a goal for me, but you need to put the work in. You can’t take shortcuts to get there. I felt this was a good chance for me to experience something a bit different, to try to improve myself.”

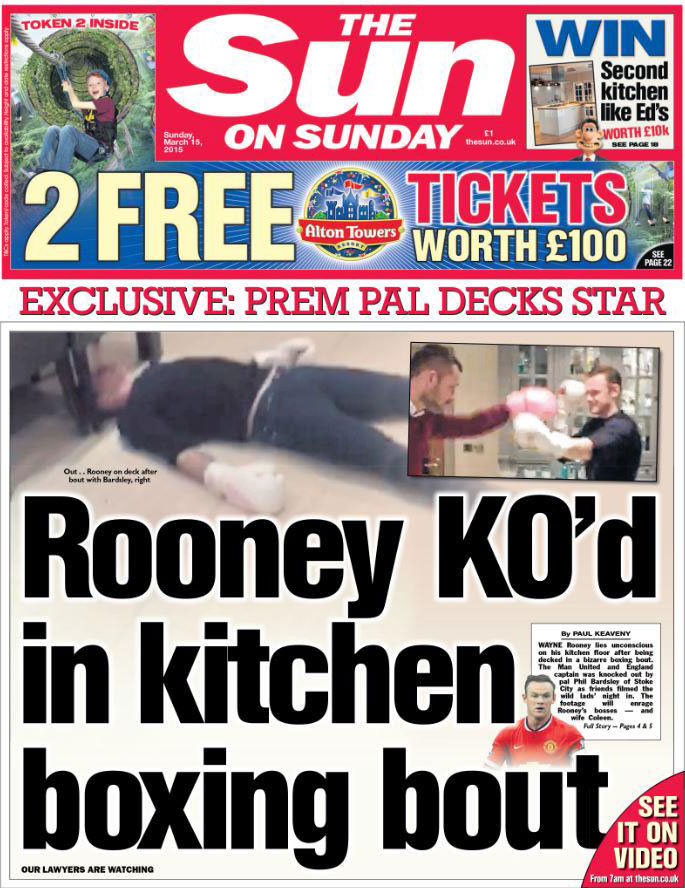

MARCH 15, 2015

Rooney speaks in a thick Scouse brogue, undiminished since his days as a teen prodigy. So much else has changed. Rooney was seen as ferocious and gifted on the field and almost comically unserious off it: a kind of ur-lad prone to boneheaded decisions, all of them gleefully chronicled by the English tabloids, none of them what you’d expect from the next great coach. But today, he fiddles with his diamond-studded wedding ring as he talks, a reminder of his wife, Coleen, and their four sons. His beard, which he strokes repeatedly, has largely transitioned from red to gray.

What is Rooney doing here? In part, he’s here to help DC United grow; in part, he’s here to show the soccer world just how much Wayne Rooney has grown. On both fronts, he has his work cut out for him.

Over the course of Rooney’s time as a player, the soccer manager’s role changed dramatically. Once an exclusive club for retired players employing the same old tactics and methods, managing became the province of highly sophisticated Renaissance men, steeped in cutting-edge analytics, sports science, and training regimens. Which is to say: The closer Rooney got to the second career he quietly envisioned, the less he seemed like a good fit.

I lived in England during Rooney’s rise. It’s hard to fully convey the depth of the national obsession with him—but to grasp his place in British culture, it helps to know the story of Paul Gascoigne, who in the 1980s rose from the working class to soccer superstardom. Nicknamed “Gazza,” he was charming and talented and hopelessly self-destructive, prone to drinking and outrageous behavior. He once greeted the owner of an Italian club he was playing for with “Tua figlia, grande tette” (rough translation: “your daughter, big t-ts”). He consorted with a sidekick nicknamed “Jimmy Five Bellies.” The tabloids adored him.

Gascoigne’s career fizzled out in the spring of 2002. At the very end, he overlapped for a few practice sessions at Everton Football Club with another working-class prodigy, just 16 years old, coming up from the team’s youth academy. A boy who was so extravagantly gifted that at age nine he scored 99 goals in a single season.

That boy was Rooney. When Gazza washed out, a vacancy opened up not only on Everton’s roster but also in England’s soccer consciousness. In the fall of 2002, before turning 17, Rooney was a sensation, the youngest player ever to score in the Premier League and for the English national team. Fans called him the “white Pelé.” In time, the headline writers came up with a different moniker: “Wazza.”

Between all of Rooney’s goals and missteps, the homage seemed to fit. It feels tawdry and tedious to get into it very deeply, so here’s the short version: There were multiple sex scandals, humiliating his wife; a drunk-driving thing; a public-intoxication-and-profanity thing at Dulles when he was playing for DC United. There was a red card in a 2006 World Cup match, a suspension for swearing into a TV camera, a ban from two matches of the 2012 European Championships for kicking an opponent. There was endless fretting over Rooney’s waistline—a boxing fan, he was built more like his pugilistic idols than a lithe footballer, despite often being the most athletic player on the field. There was breathless coverage of his hairline, which receded early, made a suspicious comeback, and then retreated once more. (Actual headline in the Sun: “Wayne Rooney’s Hair Is Thinning Again.”)

Looking back, Rooney speculates that he became a tabloid mainstay to fill not the void left by Gascoigne but rather the one created when England’s most glamorous soccer star and his Spice Girl power partner departed for Madrid in 2003. “The tabloids had gone down more of a celebrity route, and David Beckham and his wife had just left,” Rooney says. “They were really pushing for me and my wife to be that, and we’re the complete opposite to that, to that lifestyle. They were looking for another celebrity couple, if you like. We didn’t give them, really, what they wanted. That obviously caused a bit of a bad relationship between myself and the press. It was really uncomfortable at the time.”

Rooney grew up in Croxteth, a scruffy suburb of Liverpool. Like most English soccer players, he had no formal education past the equivalent of tenth grade. He was ill-equipped to handle disorienting fame and riches. It probably didn’t help that he got a tattoo reading “Just Enough Education to Perform,” the title of his favorite Stereophonics album. (Naturally, the band played at his wedding to Coleen. So did the boy band Westlife. It was that kind of wedding.) As a teenager, Rooney looked so dazed staring into the cameras that it was rumored he was illiterate. He seemed incapable of and uninterested in explaining his genius. Before he legally became an adult, he was cast as a character: an idiot-savant man-child, vain and vacant, blessed with an extraordinary aptitude for soccer and absolutely nothing else.

None of this was particularly fair. Rooney was not Beckham, with the polish and the winsome looks and the pop-star spouse: He and Coleen had some of their earliest dates in chip shops—English staples where you can eat fried things very cheaply—long before either became famous. Nor was he Gascoigne, bedeviled by serious substance-abuse and mental-health issues. In truth, Rooney had a profound grasp of the game; you cannot play as well as he did without a nimble brain, reading a chess board where every piece is sentient and forever manipulating space. Yet even as he matured into a settled family man, his old image stuck. “For me, for me family, it’s something which was a long time ago in the past, and we’ve moved on from that,” Rooney says. “I don’t think it’s ever been shaken off, because certain people won’t allow it to be shaken off.”

Rooney’s evolution was evident during his first tour with DC United, provided you cared to look. Named team captain after just three games, he finished the 2018 season as finalist for the MLS Most Valuable Player award. In the last minute of a 2–2 game against Orlando City SC, he made a play for the ages: sprinting 50 yards to chase down an opponent who was heading for an empty net, winning back the ball, and then sending a long, seemingly laser-guided pass to teammate Luciano Acosta, whose game-winning header sent Audi Field into pandemonium.

Behind the scenes, Rooney was already authoring his next chapter. As part of his deal with DC United, the team flew an instructor to the US to help him work toward an English coaching certification, required for a career in management. “When Wayne played for us, he was really like a coach on the field,” says DC United co-owner Jason Levien. “He has such a high soccer IQ, such great leadership skills.”

Wazza made a final cameo in late 2018, when Rooney—reportedly disoriented after consuming three mixed drinks and a prescription sleeping pill on his flight back from a promotional trip to Saudi Arabia—was arrested at Dulles and charged with public swearing and intoxication, a misdemeanor resulting in a $25 fine and $91 in fees. Mostly, though, he made a good impression. When DC United flew economy class, a first in Rooney’s career, he would sit in his middle seat without making a fuss. Teammates remember him as accessible and generous, someone who enjoyed footing the bill for outings and used his clout to improve life for the entire locker room, pressing the team to use more charter planes and calling out the league for its low salaries for American players and lack of free agency.

In 2020, Rooney left DC United, with two years and as much as $10 million remaining on his contract, to become a player-coach for Derby County FC, a second-division English team. Coleen and their four boys hadn’t taken to life in the Washington area—the family had never before lived outside the northwest of England—and besides, it was a good opportunity. Within a year, he had retired and become Derby’s manager.

The job was difficult, almost cursed. Derby had been badly mismanaged as a business and had severe financial problems. Rooney lost most of his better players and couldn’t sign new ones. The pandemic was in full swing. Still, he kept Derby from being relegated to a lower tier of English soccer. In 2021, the team began the season with even less talent and was docked 21 points in the standings, a punishment for past financial shenanigans. Those penalties wiped out half of the team’s eventual 14 wins, enough to drop Derby to the third-tier League One.

Rooney resigned afterward, calling his time with the club a “roller coaster of emotions.” His ability to remain calm—and wring lemonade from what amounted to a bag of rinds—impressed many. It turned out that the man the papers called an “idiot,” a “fool,” a “Roonatic,” and “loony Rooney” was a thinker of the game, adept at shuffling lineups and formations. He was also an emotional rock. “At Derby, we had a really traumatic time with ownership issues, but the way he kept together a group of staff that was getting quite a lot of negative stuff thrown at us, it was really special,” says DC United assistant coach Pete Shuttleworth, a former Derby assistant who, along with DC United sports performance director Luke Jenkinson, followed Rooney to Washington. “That’s what he builds. He builds connections. He builds trust.”

Sports history’s dustbin is littered with great players who flopped as coaches largely because they couldn’t relate to the struggles of lesser players. By all accounts, Rooney has a knack for what soccer pundits call “man management,” the fuzzy but vital skill of empathizing with individual athletes. “Every player needs something different,” he says. “Some players need encouragement. Some players need an arm ’round their shoulder. Some players need you to be a bit more forceful with them.” Rooney may have been a prodigy, but he also grew up the eldest of three sons to an underemployed laborer and a part-time cleaner. He may be a superstar, but he also understands what it’s like to fail, under the lights, in front of everyone.

“I’m not crazy,” he says. “I’m not expecting players to be able to do what maybe I could do. I’m not expecting me players to be able to have them magic moments that very few players can do. I’m not under any illusions I’m going to come in and make a player from this level to go and compete at the top level. But I think there are small steps we can take to try and improve.”

Before DC United heads out for practice, Shuttleworth runs a video review session. Rooney occasionally makes a remark or joke but is otherwise quiet. He tends to let his staff work independently, hanging back and observing, waiting until a few days before the next match to implement his game plan.

This is rare for young coaches, who often feel they have to micromanage—perhaps out of ego, perhaps out of insecurity. Rooney isn’t arrogant, but he works with the confidence of a man whose accomplishments precede him. “[It’s] really unusual,” Shuttleworth says. “I’ve been in football quite a long time. A lot of new coaches are very hands-on with everything. [Rooney] never wants credit for anything. He’ll take the blame for anything that goes wrong.”

“He’s someone you wanna go out and fight for. Every single thing that comes out of his mouth, you respect as a player.”

After Derby, Rooney was linked in the press with Everton, his first Premier League team. Instead, he came back to DC United. The setting was familiar, and the money—reportedly around $1 million a year, the most the franchise has ever paid a head coach—was nice, though it’s estimated that Rooney earned more than $100 million as a player. Mostly, he didn’t feel ready for the big time. He wanted to continue his apprenticeship and work in relative quiet. Washington fit the bill. “The one thing about Wayne is, as a manager and even as a player, he never seemed to be in a rush, in a hurry,” Levien says. “He was someone that took his time and built his career the right way.”

DC United isn’t Derby—for starters, the team isn’t struggling to make payroll—but it has floundered since Rooney’s departure as a player, missing the postseason and looking little like the organization that won four MLS Cups between 1996 and 2004. When Rooney took over last July, about halfway through the season, the team won his first game as a head coach. It lost nine of its next 13, with three ties and just one victory, finishing dead last in MLS.

During that ghastly stretch, forward Taxi Fountas was accused of calling an Inter Miami player the N-word during a game. (Fountas denied using the word; a subsequent league investigation did not find his denial credible but was unable to confirm what he said.) Inter Miami coach Phil Neville considered removing his team from the field, but after a discussion among Neville, Rooney, and the referee, Rooney pulled Fountas and play continued. During a 6–0 home loss to Philadelphia last August, Rooney again projected calm, purposely keeping quiet to see which of his players would step up.

His demeanor during difficult moments was a sharp contrast to his playing days, when Rooney often looked like an unguided human missile, forever getting into the faces of opponents and referees. With DC United, he’s serious and studious. He speaks softly, rarely—and thus impactfully, because he talks only when he has something urgent to say. “He’s someone you wanna go out and fight for,” says DC United midfielder Russell Canouse. “Every single thing that comes out of his mouth, you respect as a player.”

This season, DC United was 1–4–2 as of mid-April. However, the team has been more competitive than in 2022, arguably a few fortunate bounces away from the league’s middle tier. Rooney eats his meals with his players, chatting about shows they’ve been watching. When Canouse became a father, Rooney encouraged him to take a paternity leave, still unusual in professional sports. “He definitely has that personal relationship with each player on the team,” says team captain and defender Steve Birnbaum.

Away from DC United, Rooney calls his life “boring.” He means that in a good way. He gets recognized around Washington, but also left alone. He can go to the movies, get coffee, walk around like a normal person. He lives in Leesburg with his fellow English coaches, just minutes from the practice facility, where they watch as many as six games in a day. “We never stop talking football,” says Shuttleworth, one of those housemates. “We like to watch a lot of football, and we’ll dissect it. Sometimes he’s just sitting there on the sofa and we’re just chatting away about whatever’s on the telly—you forget it’s Wayne Rooney.”

How long Rooney will stick around is unclear. His family has remained in England, visiting during school breaks. He heads home when he has a few days off. “Me coming here, I miss a lot of big moments in me children’s lives,” Rooney says. His 18-month contract with DC United expires after this season; reportedly, it contains language allowing him to leave at any time to take a Premier League job. The tabloids call it the “Coleen clause.” “If [Wayne] has an opportunity to go to a [Premier League] club, I wish him the best,” says Dave Kasper, DC United’s president of soccer operations and sporting director.

For now, Rooney appears content to follow the road map he has given his players: Take small steps and try to improve. Growth by DC United will reflect his own. “As a player, I was fortunate enough to, really for the majority of my career, choose me pathway of which club I wanted to go to,” Rooney says. “As a coach, I’m no longer at that level. I’m back to a learning level and trying to progress up that ladder.” Back on the practice field, he instructs the team, somehow managing to turn away slightly each time a photographer for this magazine lines up a clear shot. It’s probably an unconscious habit, honed from a lifetime of ducking paparazzi. But in a way, it fits. The more Wayne Rooney disappears into coaching, the more he allows himself to be seen.

This article appears in the May 2023 issue of Washingtonian.