When I visited the Temperance Alley Garden behind the U Street Metro stop on Saturday, it felt more like a block party than a community gardening day. There were about 30 people there, mostly in their 20s and 30s. Almost everyone there had a job to do and seemed happy to be doing it, dirtying their hands and knees without hesitation. Bok choy, tomatoes, and hot peppers were being harvested, new plants were being sowed and watered, mulberries were being picked and eaten, and some people were just relaxing under the pavilion. Different areas of the garden served as “rooms” with different vibes and purposes.

“At the garden we always say that, right now, you’re sitting in somebody’s living room in the past. And you’re sitting in somebody’s living room in the future,” said Aaron Z. Lewis, 28, the president of the U Street Neighborhood Association and one of the green space’s main stewards. “And right now we’re in this special window of time where it’s a community garden.”

That window won’t be open much longer: This fall, the pavilion and raised beds in Temperance Alley will be razed to make way for “Temperance Mews,” a mixed-use development that will feature apartments, a hotel, and retail.

Lewis says the project’s ephemerality has been key to its existence. He and his former roommate Benjamin Hanes started to notice the space at the beginning of the pandemic. It was always locked up, with barbed wire around the fences and weeds that struggled to break through the asphalt. The pair, he says, wondered whether they could turn it into a community gathering space.

So Lewis, Hanes, and other neighborhood residents worked out a temporary lease agreement with Eastbanc Real Estate and Jamestown, which plan to develop the plot. In 2020, they essentially asked Eastbanc for permission and support to “animate” the space while it sat unused. After months of hard work, Temperance Alley Garden was born.

“I don’t think this project would have happened if it weren’t temporary,” Lewis says. “Its temporariness and its existence are so intertwined.”

That expiration date has also created a sense of urgency among the community, a reason for going there now, as opposed to putting it off for another weekend. And it’s that urgency that has been so successful in bringing that community together.

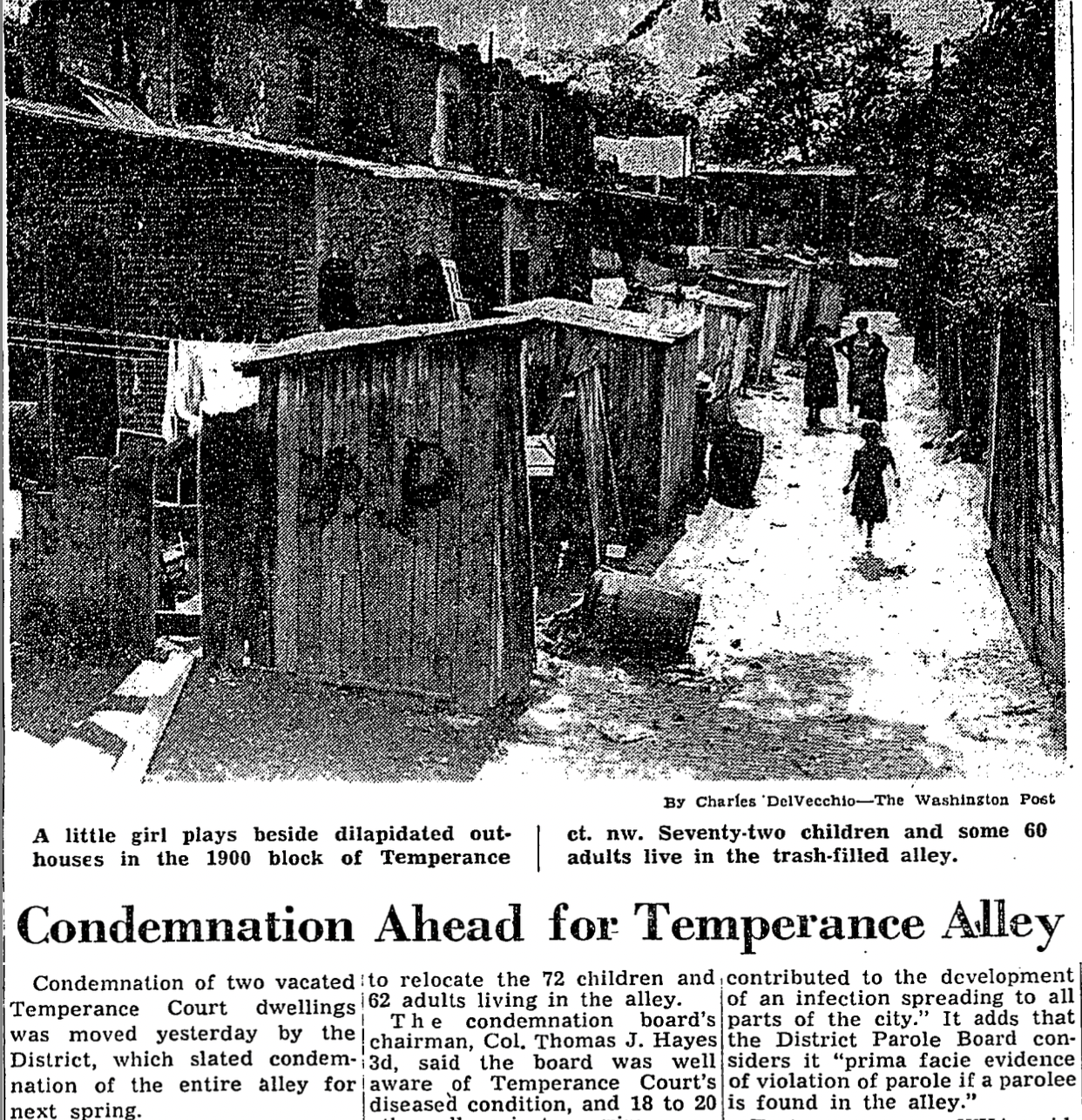

Instead of focusing on the last days, Lewis and the other stewards have emphasized that the garden is just one event on the long timeline of Temperance Alley. The alleyway was first used as poorly constructed tenement housing for recently freed Black slaves after the Civil War. It continued to be a space for working class Black folk through the Great Migrations of the early 20th century, even while legislators and reformers like Jacob Riis called for its destruction. Eventually the dwellings were destroyed in 1953, and the Black laborers who called it home were forced out with no replacement housing offered. After years of multiple failed attempts to create affordable housing in the alleyway, Eastbanc acquired the land in 2012 with initial plans to construct 15 townhouses.

“I think it’s really cool to be able to place yourself in time to understand when you are in the context of a larger story, and how that relates to where you’re sitting right now,” Lewis says. “Once you know where you are, how and when you are, and how you fit into that story, then it’s about reshaping and caring for the built environment in a way that’s integrated with both the past and with what’s to come.”

As gardeners filed out of the alley with the produce they harvested (no one “owns” the multiple garden plots there; whoever comes and contributes is welcome to take some home) I couldn’t help but wonder: Why can’t a city in need of both housing and community garden space have both of those things? The Temperance Alley stewards have already accepted the reality of the situation. They created a beautiful garden and brought their community together when everyone needed it most. They plan to use the space until the very last day of its lease.

“What we tried to cultivate wasn’t just a space where you’re anonymous to the other people, where you’ve got your headphones in, chilling with your book. We tried to cultivate a space where people feel invited and encouraged to get to know each other,” Lewis says. “It’s really oriented towards neighborhood-building and relationship-building more than it is just another green space.”