A black unmarked truck is rumbling across Chain Bridge, its back seat piled with camo, firearms, coolers, and gear. Up front are two game wardens with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources.

“The water is so low,” one says, eyeing the Potomac out the window. “The lowest I’ve ever seen it in my career.”

Over the bridge, on the Virginia side, they stash their truck in a gulch by the woods, hike a deer trail, then split up. One descends the hill toward the river. The other climbs a steep bluff, stopping by a stand of oaks. Beneath him, a small stream empties into the Potomac, and he trains his binoculars on its mouth. There, he sees it: white glimmers on the water, the surface churning with fish. The herring are here, leaping into the tide pools. The spawning run is on.

Each spring, from the depths of the North Atlantic, millions of herring migrate up coastal rivers in vast schools, often crossing hundreds of miles to spawn. For weeks, they battle the currents, the predators, the pollution, the storms, drawn irrevocably to their natal waters—the streams and creeks where they were born—where they’ll shoot clouds of roe and milt into the water, then ride the current back out to sea. For many of them, Chain Bridge is the finish line; beneath its concrete piers is the mouth of Pimmit Run, a small creek choked with rocks and industrial rubble, one of the best herring hatcheries around.

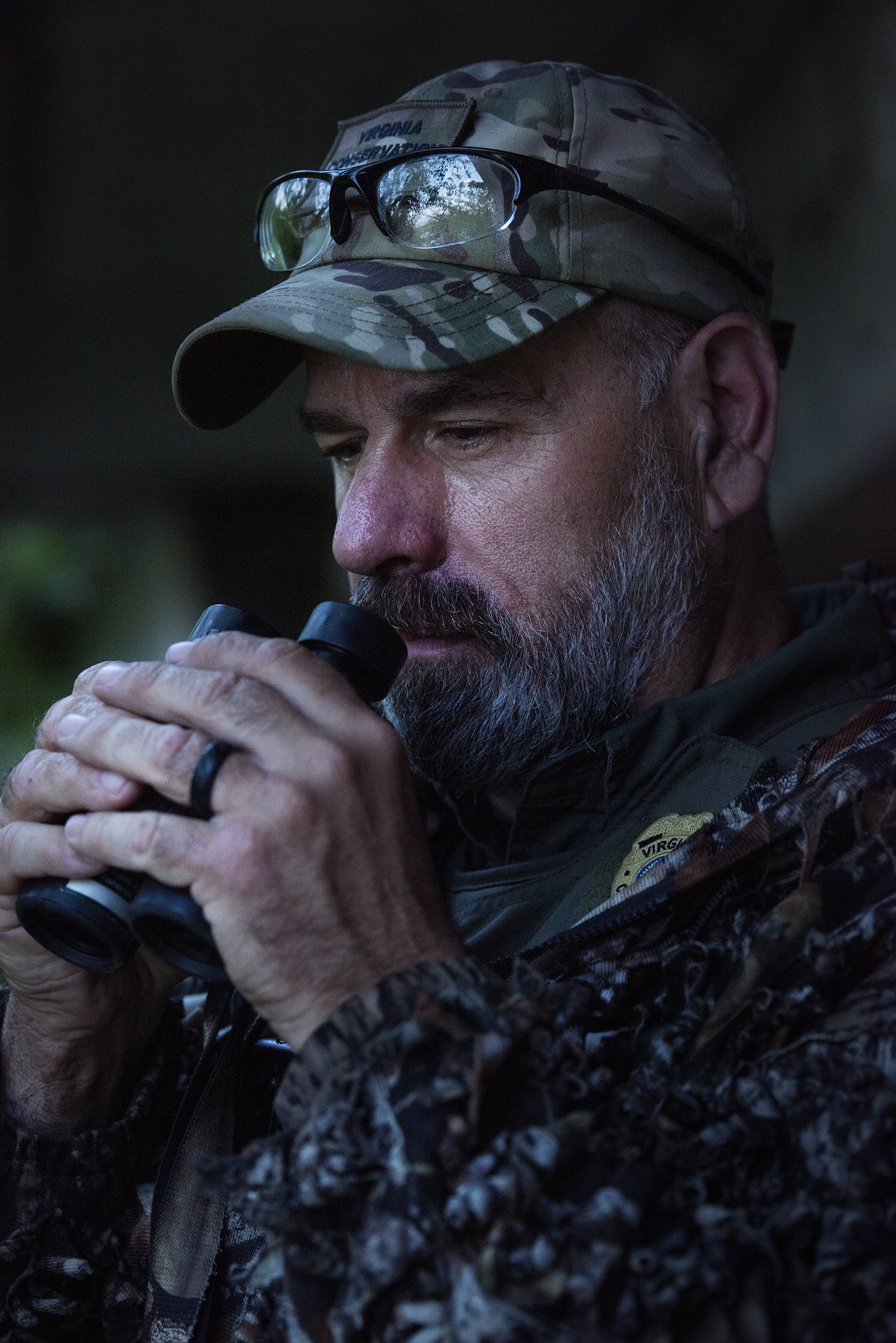

With one hand, Sergeant Rich Goszka holds his binoculars to his face, and with the other, he grabs his phone. “There’s fish in the eddy and they’re trying to spawn right now,” he tells his partner, Mark Sanitra, who’s camouflaged somewhere below. “I can see them flashing from up on this hill.” Just then, a man in a gray shirt wanders a few dozen feet up the creek and sticks his hands into the water. “Yeah, I see him,” Goszka says, his voice testy. “Hang on—just hang on. Yeah, he’s trying to catch them by hand.”

Wading up to his thighs, the man is moving his arms through the water, as though he’s trying to herd the fish. After a moment, he pulls one out—a silvery creature about the length of a shoe. “He’s got one!” Goszka shouts into the phone. “He caught one by hand. Did he just throw it down? He might have put it on the bank.”

Regardless of where the fish ends up, the man has committed a Class 2 misdemeanor: In Virginia, catching herring is banned. Across the East Coast, the herring population is near historic lows. It’s the most imperiled of the Potomac’s fish. For that reason, you can’t target them by hand, or by net, or by hook-and-line—not at any time of the year, nor at any stage of maturity, even if you release them back into the water. (While fishing legally, you’re unlikely to catch them by accident, since they don’t bite on regular bait.) But while both officers saw the man unlawfully possess a herring, neither saw where he put it. That’s a problem; if the officers don’t have the fish, they don’t have a case.

For an hour or so, Sanitra watches from the bushes—he’s almost invisible, a camo suit zipped over his Kevlar vest—while Goszka sits high up on the bridge abutment, hidden by trees, staring through his binoculars. The man in gray smokes a joint, lounges on the rocks with his friend, and takes pictures with his phone. Cormorants swoop overhead while blue herons hunt from the banks. The sinking sun turns the water to chrome. Then Goszka sees it: The man wades back in, grabs two more herring, pinches their gills to kill them, and stuffs them into a bag. If Goszka searches the bag, he’ll find the fish. There’s the ticketable offense.

Maybe this sounds petty, spying on a guy who’s enjoying a sunny April evening, then slapping him with $150 in fines and court fees for taking a couple of fish from Pimmit Run. Maybe it even looks like harassment. Goszka understands that perspective. But the way he sees it, game wardens serve a higher calling. “Wildlife doesn’t have a voice,” he says, “so we have to be the voice of it.”

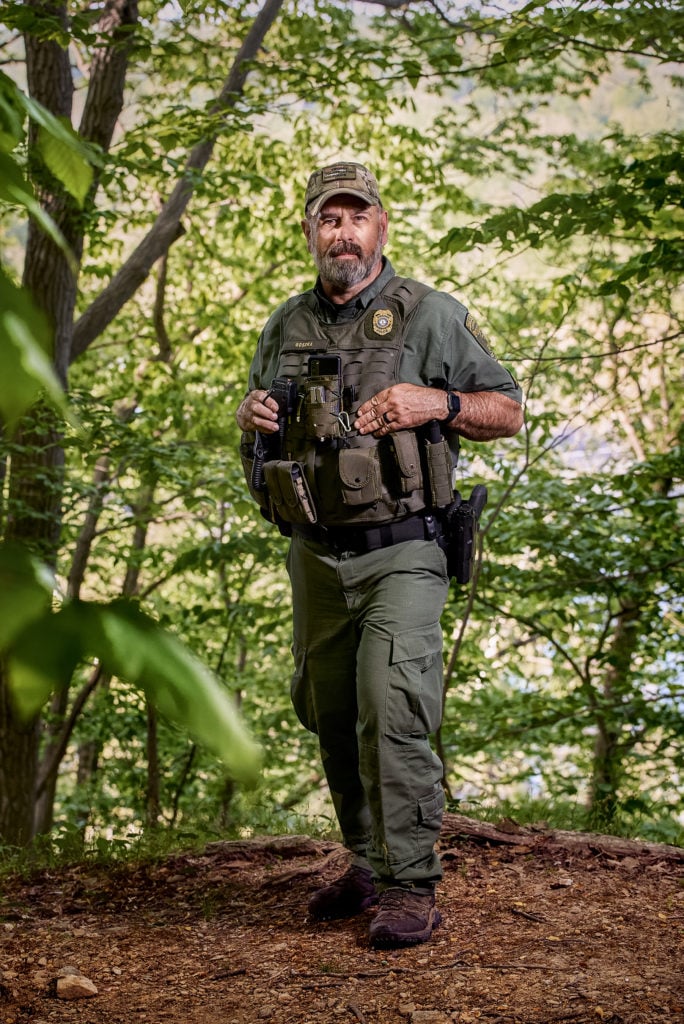

The sergeant in charge of the herring run, Goszka is a wiry man of 55, bearded and muscular, a 25-year veteran of the Virginia Conservation Police. Before that, he was a game warden in his home state of New Jersey, and before that, he was a kid who loved to hunt and fish. Now he protects all sorts of wildlife—deer, turkey, songbirds, bears—but he’s most passionate about species like herring, “the ones that need the greatest protection, things that are native, that get over-harvested or exploited pretty quick.”

In rural areas, where hunting and fishing are rooted in the culture, people know what a game warden does—but the job can seem mysterious somewhere urban like Northern Virginia. “People think we rescue animals all the time,” Goszka says. “They think we’re park rangers.” Actually, game wardens are more like cops. With guns and badges, they patrol the woods, fields, and waterways of the region, enforcing fish and wildlife laws.

Sometimes, that work is intense. There’s a small portion of the hunting population that “likes to really slaughter stuff,” Goszka explains—the guy in the Northern Neck rumored to have skinned foxes alive, his friend who killed more than 200 turkeys, an operation in Loudoun charged with shooting 90-some wood ducks in just a few days. He’s also seen poachers with strange fetishes. “People get fascinated by big buck antlers,” Goszka says, “or they get a thrill out of killing turkeys and they keep all the beards and spurs.” He describes them as “sociopaths, but on a level that doesn’t really affect people. They become like serial killers, but for wildlife.”

Goszaka sees game wardens serving a higher calling: “Wildlife doesn’t have a voice, so we have to be the voice of it.”

The spawning runs, though, tend not to attract the worst poachers. Herring are small fish, bony and lean. When people take them illegally, it’s not typically to eat or sell, but simply to use as bait. In the water, the skin of a herring wafts an oil irresistible to bigger fish like catfish, snakehead, and perch—ones whose flesh makes better meals. Sometimes, officers see fishermen casting bits of herring into the river. According to Goszka, they’re often far more successful than those fishing with legal bait.

Occasionally, Goszka says, violators object that it’s not a big deal to pull a few herring from a teeming springtime stream. But “right now, the herring population is so low that it can’t withstand a recreational harvest, or even catch-and-release fishing,” says John Odenkirk, a biologist with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources. At this point, he says, “we need to try to ensure the survival of as many fish as possible.” The law agrees.

In 2012, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission—a federal regulator—handed down a coast-wide moratorium on harvesting alewife and blueback herring, collectively known as “river herring,” which are the types found in the Potomac. Meant to protect the population, the law also has broader aims. Herring are a keystone species, a fish that’s important to many animals’ diets: beloved wildlife like blue herons and bald eagles, sport fish like striped bass, grocery staples like tuna and marlin. When the game wardens protect the herring, they’re safeguarding the ecosystems that are built on their backs.

In the early 1600s, when the English first settled in Virginia, the notion of depleting the rivers would have been unimaginable. In writings from the period—quoted in John C. Pearson’s “The Fish and Fisheries of Colonial Virginia”—the colonists are astonished by the number and variety of fish: Rockfish and oysters. Sturgeon and trout. Flounder, eels, perch, and carp. In 1608, on a voyage to the Chesapeake Bay, Captain John Smith saw fish “lying so thicke with their heads above the water” that, not having brought any fishing gear, he tried to harvest them with a frying pan.

Of particular note were the runs of anadromous fish—species like herring and shad that live in the ocean but return to freshwater to spawn. Each spring, the colonists watched in disbelief as “great sculles of Herings” and “shads of a great bignesse” flocked into the rivers to breed. These fish got so thick as to cause problems for boats. In 1705, historian Robert Beverly wrote that the “Herrings come up in such abundance into their Brooks and Foards to spawn, that [it’s] almost impossible to ride through without treading on them.”

But already, trouble was brewing. In the 1670s, a court in Tidewater received complaints about the colonists’ “excessive and immoderate striking and destroying of Fish,” which would “wound four times the quantity that they take” and “affright the Fish from coming into the rivers and creeks.” By 1745, Virginia’s waterways were so clotted with fishing infrastructure—weirs, stone-stops, pound nets, seines—that some boats could no longer navigate.

Many of these obstructions related to herring, which by the late 1700s was the colony’s most important commercial fishery. While running up the rivers, the fish would be scooped out of the water, salt-cured or dried, and exported by the barrelful to the West Indies and various American cities. Even George Washington took part. Enslaved people at Mount Vernon operated large nets in the Potomac, and their typical springtime catch was reported to be over a million fish. This was, apparently, among Washington’s most substantial sources of income, eclipsing most of his crops.

The colony’s first fishing restriction, handed down in 1678, prophesied what was to come: that the region’s fisheries, if not regulated, would be “thereby spoiled to the great hurt and grievance of most of the inhabitants of this county.” For the herring, the first problem was overfishing, then other threats arose: Nineteenth-century dam-building blocked access to spawning grounds, and industrial pollutants wrecked the waterways.

Researchers can’t say exactly how many river herring existed during the species’ historical peak. But in the 1950s—after decades of decline—the East Coast’s commercial fishermen were landing around 60 million pounds of them a year. By the late 1990s, annual commercial landings plunged to about 2 million pounds. They’ve basically flatlined ever since.

After dark on the first Friday of herring enforcement, Pimmit Run is a light show: headlamps bouncing down the trail, bonfires on the banks in DC, beams from flashlights and phones, the safety lights on boats. In the darkness, people fish from the banks, mill about the rocks, and sit on lawn chairs and coolers while music from radios wafts through the trees.

Up on the trail, the game wardens hide with night-vision scopes that make the world an eerie, glowing green. They’re looking for cast nets—huge mesh snares that sweep indiscriminately, pulling up dozens of fish in one haul. Using them is illegal at Chain Bridge. Even if thrown back, a netted herring may still die; the fabric strips its protective slime, and the stress of being caught increases mortality. Watching and listening, the officers make note of who does what. At the end, they round everyone up for tickets—15 total, the biggest night of the run.

Henry Barrera was there, fishing on the rocks with his dad and girlfriend. Earlier that day, they’d bought a cast net at Dick’s, which they were throwing into the Potomac for perch. If they caught any herring, the family didn’t keep them. “To be honest, we’ve taken some home before and cooked them,” Barrera says, “but it’s not a lot of meat, so now we just throw them back.”

Barrera’s dad had about eight perch in a bucket when some men emerged from the woods and told him to stop. At first, Barrera was confused. “They came out of nowhere,” he says. “I didn’t even see them until they were already there.” These men weren’t in uniform—they were in regular civilian clothes. “That’s why I was like, I’m not too sure if these are really cops. ”

The plainclothes officers explained the problem: that while perch were fine to take, cast-netting is illegal. Barrera says his family didn’t know. Because his dad was the one with the net, the court summons went to him. Perhaps the wardens could have given a warning—though Goszka says those rarely work.

The utility of a ticket, Goszka says, is that people talk about it. They tell their friends. Barrera did; he warned the ones who fish at Chain Bridge—who’d told him the river was mobbed with perch—that his dad was going to have to go to court. And when you write 15 tickets in a night, word ripples out that officers are afoot. “That’s part of the myth of being a game warden, that we’re behind every bush and tree,” Goszka says. “That’s the idea we want people to have.”

In a way, catching poachers is similar to hunting. The skill sets are parallel: covertly watching a target, predicting behavior, and interpreting abnormal cues. Goszka is explicit about it. “People have the equivalent intelligence as you, so you’re hunting something that can outmaneuver you,” he says. “It’s a cat-and-mouse game with the ultimate prey.”

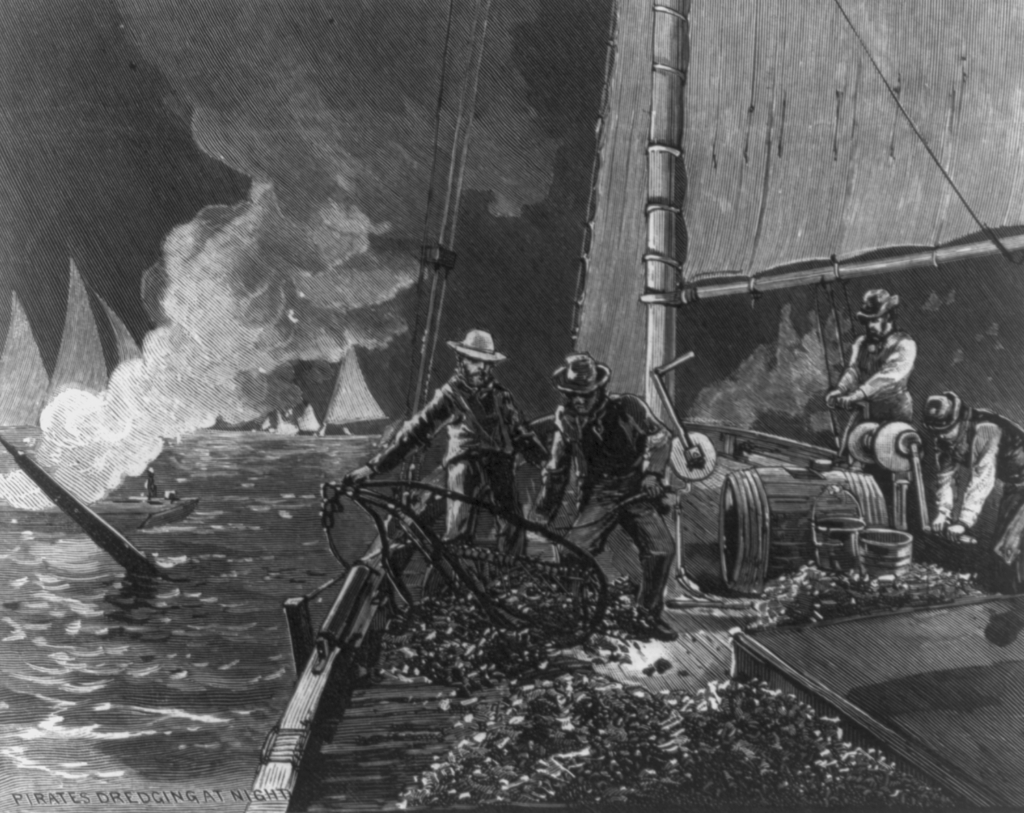

Historically, this dynamic has been explosive. “Maryland used to have gunships,” Goszka says. “That’s how bad it got.” He’s talking about the Oyster Wars, a series of bloody conflicts that roiled the Chesapeake toward the end of the 19th century. What happened, in essence, is that new canning technologies ballooned the value of oysters, spurring a gold rush in the bay. For a time, the Eastern Shore was like the frontier—towns springing up overnight, brothels and saloons, outlaws and gunfights, all fueled by the promise of outrageous wealth for prospectors of the region’s “white gold.”

Initially, the fault line was between local watermen, who harvested oysters sustainably, and the industrial dredging operations that descended from New England. These dredgers took enormous quantities of oysters—sometimes illegally—while ravaging their reefs. The atmosphere was lawless; poachers and watermen shot and sometimes killed each other, while dredgers who needed labor would reportedly kidnap recent immigrants to Baltimore, forcing them to work on their crews.

In 1868, to guard the oyster beds and quell these disputes, Maryland created the State Oyster Police Force, known as the Oyster Navy. This 120-person operation cruised the bay with boat-mounted cannons, raiding dredgers and sinking ships. But from the beginning, its officers were outnumbered and outgunned. They couldn’t protect the oysters, whose population has never bounced back.

Today, armed fisheries enforcement is still the norm. Goszka patrols with a Glock on his hip. In his truck, mounted above the back seat, is an M4 rifle. In addition, officers are allowed to concealed-carry a secondary firearm in the field.

That’s a lot of firepower for a herring moratorium—but from the officers’ perspective, it’s necessary protection. Studies show that game wardens are assaulted more often than any other lawenforcement group; one researcher, looking at data from Virginia, found conservation officers to be seven times more likely than other police to be assaulted with a gun or knife. That makes sense. Especially during hunting season, they’re interacting with a population that’s disproportionately armed, often while in the woods alone.

Of course, armed officers can also be dangerous to civilians. While it’s rare for game wardens to shoot people, it happens. Locally, the most famous incident was in 1959, when officers from the Maryland Tidewater Fisheries Police conducted a moonlight raid on a boat suspected of illegally dredging oysters on the Potomac by Swan Point. As the boat fled, the officers fired 27 shots, one of them fatally wounding Berkeley Muse, a 31-year-old father of three. The state’s attorney sought manslaughter charges—the way some read the law, officers were supposed to shoot to disable the boat, not kill a fleeing man suspected of a misdemeanor offense. The grand jury voted not to indict the officers. The surviving poachers were charged.

Interacting with an armed officer can be frightening for anyone—but particularly for people whose immigration status is tenuous. That’s true of many who are ticketed for herring. These are not hardcore poachers; they’re families like Henry Barrera’s, immigrants from Latin America and Asia sitting by the Potomac with coolers of snacks and bait, kids splashing among the rocks while adults trawl the waters, often for something to eat.

“We come from Central America,” Barrera says. “My dad, he has a work permit, so he’s working here legally—but still, this was his first time dealing with cops or anything, so he was pretty shook.” During the six weeks between the summons and the court date, Barrera says, his dad was nervous: “Every once in a while, he’d be like, ‘Damn, I’m still thinking about it. What’s going to happen that day? I’ll pay a ticket, but I don’t want it to mess with my immigration or nothing.’ ”

It didn’t—Goszka says he’s never seen anyone deported, or even jailed, for a fishing violation alone—but the experience was still onerous. For using the cast net, Barrera’s dad paid $150 in fines and court fees, and he also lost a day’s wages, since he called out of his job at a Maryland window factory to go to court.

“It affects us a lot,” Barrera says. “It’s an expense that we weren’t expecting. My dad’s like, ‘That money I spent at court, I could have just gone to the store and got more fish than we actually caught.’ ” The family hasn’t been fishing since.

Up and down the coast, this is how game wardens enforce the moratorium: slapping folks with fines to protect the spawning fish. At Chain Bridge, it seems to work. After that frenetic Friday night of ticketing, activity slowed to a crawl—just a handful of people showing up each day, and far fewer of them with nets. But a separate question is whether the herring moratorium—the 2012 ban on recreational or commercial harvest—has actually helped the population bounce back.

T. Reid Nelson, a fisheries ecologist at George Mason University, runs an annual population survey of the Potomac’s herring. His assessment of the moratorium is blunt: “We haven’t seen the comeback response that people were hoping for.” It’s still early, he hedges—the law is barely a decade old. But so far, it doesn’t seem like much has changed.

That’s perplexing. In the past half century, the herring should have benefited from improved water quality, restored habitats, dam-removal efforts, and the fishing ban. They should be booming, says Odenkirk, the fisheries biologist with the state. “But herring catches are worse now than they’ve been, maybe ever, and nobody can tell you unequivocally why.”

Certainly, one factor is climate change, which is acidifying the oceans, contributing to droughts and floods, and throwing temperatures out of whack. Experts also point to commercial trawling out in the Atlantic, where river herring spend most of their lives. Sometimes, herring are scooped up accidentally by operations targeting other types of fish, then processed into goods like fertilizer, cat food, omega pills, and tinned sardines. “There’s a lot of concern,” Odenkirk says, “that these fish are just being harvested indiscriminately in international waters where we don’t have any control.”

A brooding female can carry up to 100,000 eggs—if she’s caught before she lays them, then her death will reverberate for generations to come.

If fewer adults are making it out of the oceans alive, then it’s crucial for game wardens to protect the ones that do: the spawners that run up coastal rivers, wriggling and writhing in the tide pools, releasing their roe and milt. Next year’s population size depends on the success of this year’s fish. A brooding female can carry up to 100,000 eggs—if she’s caught before she lays them, then her death will reverberate for generations to come.

On a sleepy Saturday in late April, Goszka is back at Pimmit Run, prowling the rocks in plainclothes. By now, the herring have thinned and striped bass are coming in. It’s midmorning when the clouds roll over, thick and dark, threatening an inch of rain. Goszka eyes them, muttering about the “wall of water” headed this way. He sees what’s coming—that these are the final hours of the herring run, that a hard rain will wash the last of the fish back out.

The end of the season is similar to the beginning: A little boy in a blue shirt wades into Pimmit Run, rifling around the water with his hands. He emerges with a fish. “No, no, no, no, no!” Goszka shouts. “You can’t be holding that. Throw it back.” The kid stares at Goszka, looking confused, then drops the herring onto the rocks. Pitifully, it spasms.

“Take it back over there,” Goszka says, pointing to the Potomac. In Spanish, then in English, the boy’s dad tries to protest. “He’s just a child,” he says, and Goszka’s reply is icy: “Take it back over there or I’ll charge you.” Prodded by his dad, the kid skitters down the bank and tosses the fish into the river. It probably won’t survive.

“Anytime you handle something wild, you stress it,” Goszka says. He’s furious, though he doesn’t write a ticket. From the bank, the small boy looks as though he’s been stung. He picks at a bag of McDonald’s, glowering at the game warden from afar.

Goszka is just doing his job—what the state has hired him to do, what a federal regulator determined was necessary to protect the imperiled herring. But if the herring are being smothered by the changing climate, or decimated for profit in the ocean, then is yelling at a kid or ticketing immigrant families the best way to conserve them? Goszka thinks the question is fair. “But the way I look at it,” he explains, “we still have a duty to protect what’s left of the fish, regardless of what anyone’s doing offshore. We may be only maintaining the [population’s] status quo. But that’s at least something—the herring still exist, they’re not extinct.”

Beside Goszka’s feet, the herring wriggle and writhe in a tide pool. They’re roiling the surface, bodies colliding. Quick spats fling droplets onto the rocks. Once they’ve spawned, they go limp, flushed from the mouth by the current. First, they fall into the Potomac, then they’re washed back toward the bay, and finally into the ocean.

Along the way, some will be eaten—by turtles, eagles, bears, raccoons—and feasting wildlife will bloom on the riverbanks. Of the surviving fish, many will return to Pimmit Run several more times during their lives, guided by forces almost supernatural to spawn in the same tiny stream where they were born.

As the clouds gather, the fish are still flipping, still seeding the substrate with life. The rains come at noon, and the fishermen trickle out. Beneath the water’s surface, the young herring are already growing. Goszka is the last to leave.

This article appears in the October 2023 issue of Washingtonian.