This post was updated on November 4, 2024.

Election Day deals and specials have become a regular reward for carrying out one’s civic duty. But here’s the thing–those well-intended gestures run the risk of violating federal law. Offering something of monetary value—a discount, a free appetizer with a purchase, etc.—that could influence whether or not someone votes is in violation of US Code § 597. Violation of this law could result in a $1,000 fine or up to two years of jail time.

But has the existence of this law ever really stopped anybody? The short answer is no.

“The federal law has never been enforced,” says Todd Belt, a professor of political management at George Washington University. “People see it as a do-gooder act, and they only see it from the standpoint of it helping democracy.”

Belt also notes that these laws have a very simple workaround: So long as the deal offering is available to anyone, not just those with “I Voted” stickers or other proof of voting, restaurants and bars are in the clear. But, no one’s paying much attention anyway.

“[Federal law enforcement] have much more important things to do and not enough resources to enforce the law, which, in this day and age, really doesn’t seem to have much criminal impact on the world,” he says.

Vote-buying was a bigger issue in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before the days of secret ballots and state-run elections when party members could tell who voted for who. It was federally criminalized in 1925, with changes to language and penalties throughout the years now reflected in Code § 597. But today, it doesn’t appear that a free doughnut or 20 percent discount is turning out voters who weren’t heading to the polls in the first place.

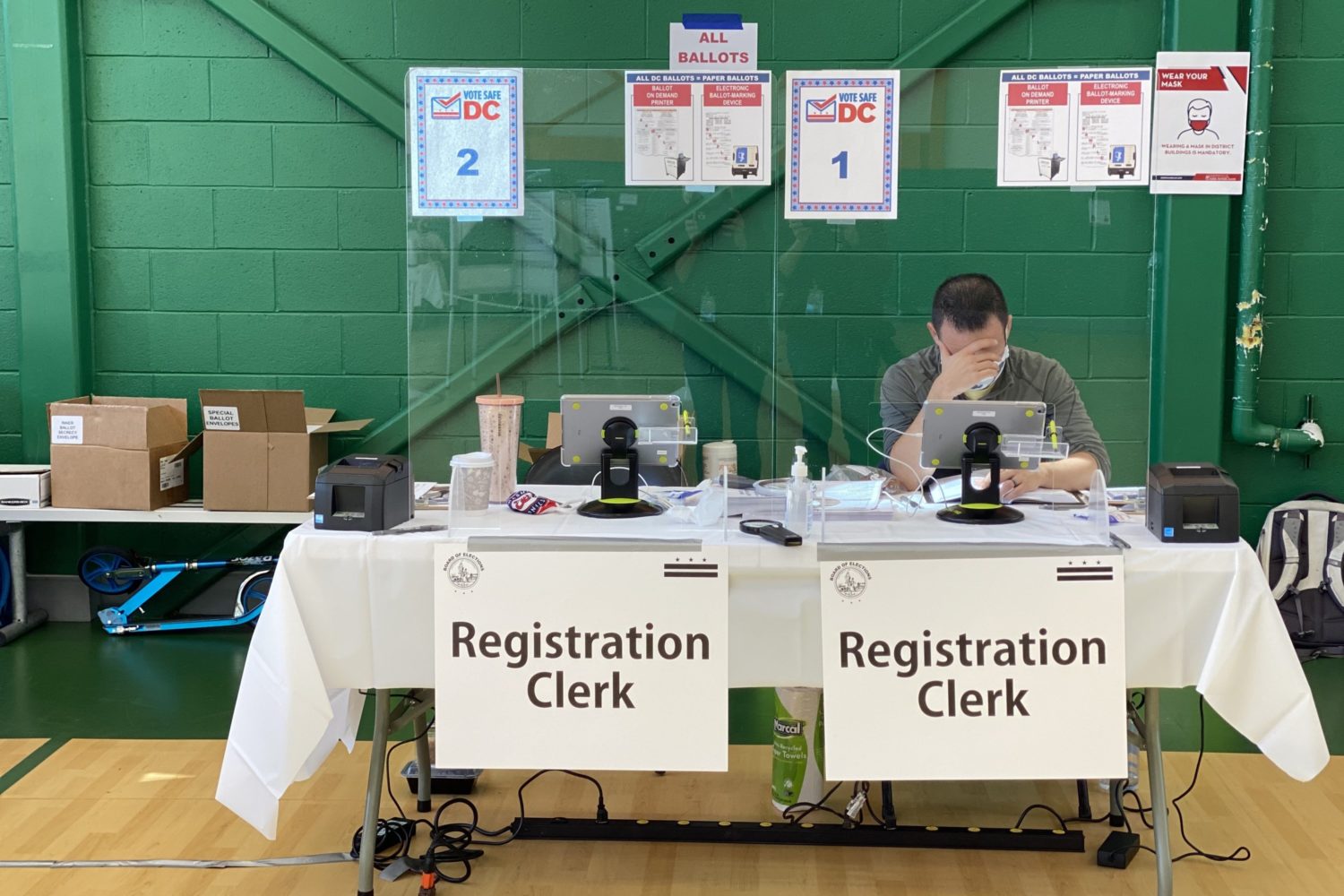

Code § 597 only applies to federal elections, but some states have passed their own related laws. Virginia does have a voting influence law on the books. Washingtonian contacted several election law experts and the Virginia Department of Elections to determine whether enforcing this law is similarly neglected but was unable to reach anyone for comment.

“I think that it’s really outlived its lifetime,” Belt says. “And, as someone who likes to promote democracy and voting, I don’t see too much harm in it.”