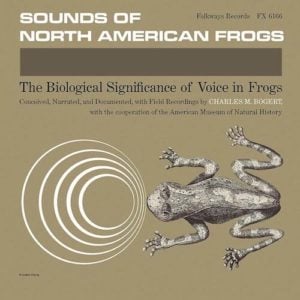

When it comes to frog noises, most people’s knowledge basically begins and ends with the word “ribbit.” Should anyone want to change that sad reality, Smithsonian Folkways is here to help. The 75-year-old record label—which has more than 60,000 recordings in its collection, from Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly to oddball classics like Speech After the Removal of the Larynx—has lately been reissuing highlights on vinyl, and recently they got around to a cult favorite: Sounds of North American Frogs. The spiffy new edition, which has been remastered from the original tapes and faithfully reproduces its distinctive packaging, marks the first time it’s been available as an LP since its release in 1958. “This is one of those records that people are always asking, ‘When are you going to put it out on vinyl?’ ” says Maureen Loughran, director and curator of Smithsonian Folkways. “So it was time we did.”

What accounts for the enduring popularity of this compendium of swampy croaks and buzzes? The guy who made it, renowned herpetologist Charles Bogert, isn’t around to speculate: He died in 1992. So it’s up to admirers to figure out the odd appeal of the record, which features almost 100 close-miked mating calls and warning chirps from various amphibians (along with grandpa-voiced commentary from Bogert). The album was reissued on CD in 1998, and many fans discovered it back then on college radio, where it was something of a novelty-album favorite. “It seems to have caught hold of our audience in a deep and profound way,” says Loughran. “I can’t explain that, necessarily.”

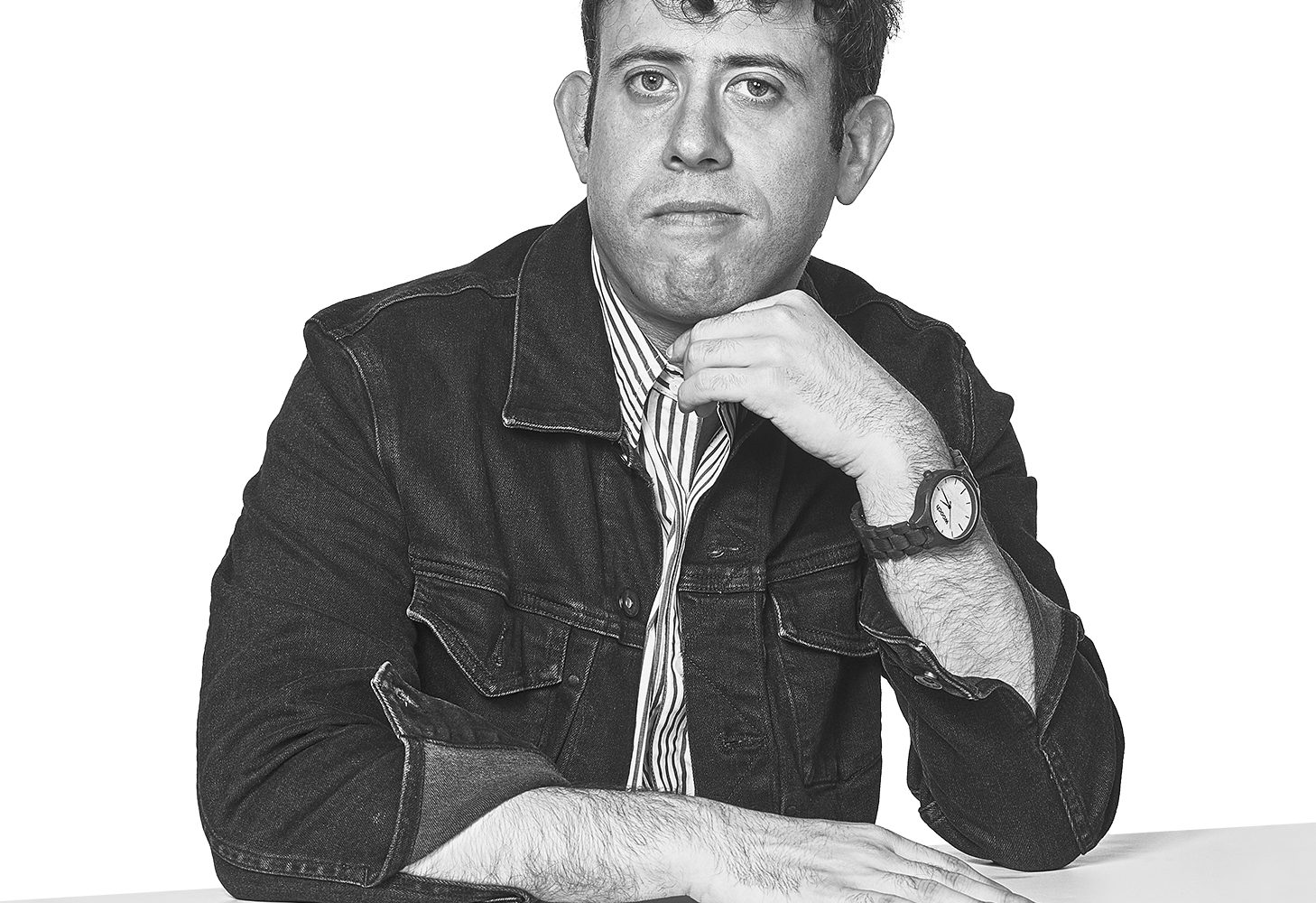

Hoping for a bit more insight, we called up Matmos, the Baltimore-based electronic-music duo that just released Return to Archive, an album constructed of sounds sampled from Folkways recordings (including Sounds of North American Frogs). Matmos’ Drew Daniel finds himself drawn to the amphibian calls for a couple of reasons. “One is when it approximates human speech,” he says. “There’s something kind of operatic in it. And at the opposite end of the spectrum, there’s piercing tones that sound—like somebody with a modular synthesizer in the in the early ’60s. It’s both human and deeply inhuman.”

But maybe to really get it, you have to talk to a frog expert. Conservation biologist Brian Gratwicke, who oversees the amphibian conservation programs at the National Zoo, wasn’t familiar with Sounds of North American Frogs, but in response to an interview request about it, he immediately bought the album and dove in. He was impressed. “These are really top-class amphibian call recordings,” he says. “To go out and find them in their reproductive state in calling season, when you’ve got a good, clear call without a whole load of other background chorus going on, is very challenging to do. And some of these frogs are very difficult to actually find. I don’t know if you’ve been out looking for spring peepers, but they can be a bit ventriloquistic. You can think you’re hearing them coming from somewhere, and they’re actually coming from somewhere else.”

Gratwicke knows what he’s talking about when it comes to frog recordings: He’s currently studying endangered Panamanian frogs, and their calls often pop up on his iTunes. He’ll be listening to Belle & Sebastian or the Postal Service, and “suddenly, there’ll be the voice of my colleague from Panama who recorded all the frog sounds and he’ll say, ‘this is leptodactylus pentadactylus,’ and then it goes ‘woop! woop! woop!’ ” (Yes, there are frogs that go “woop!” If that surprises you, we’ve got a cool amphibian-sound album to recommend.)

Now Gratwicke is excited to add Sounds of North American Frogs to his collection. “Every one of the calls on this album is a story that’s been told for thousands of years,” he says. “They’re the soundtrack of nature. And that is part of who we are on this planet. Our ancestors have shared these stories with the frogs at night as they’ve been sitting around the campfire. That’s really magical.”