Not even a year after taking office, it looks like George Santos, the New York Republican and self-appointed “It girl” of Congress, is facing a third vote to expel him from the body—perhaps not surprising for a lawmaker whose time in office has been defined less by legislating than by serial fabrication, alleged financial misconduct, and a 15-foot-tall balloon doppelgänger that (fittingly!) wouldn’t be out of place on a used car lot.

If the required two-third’s majority of the House does vote to expel Santos from office, he will join a five-member group that is as exclusive as it is unenviable. With help from Dr. Ray Smock, interim director of the Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education, we’ve complied a full list:

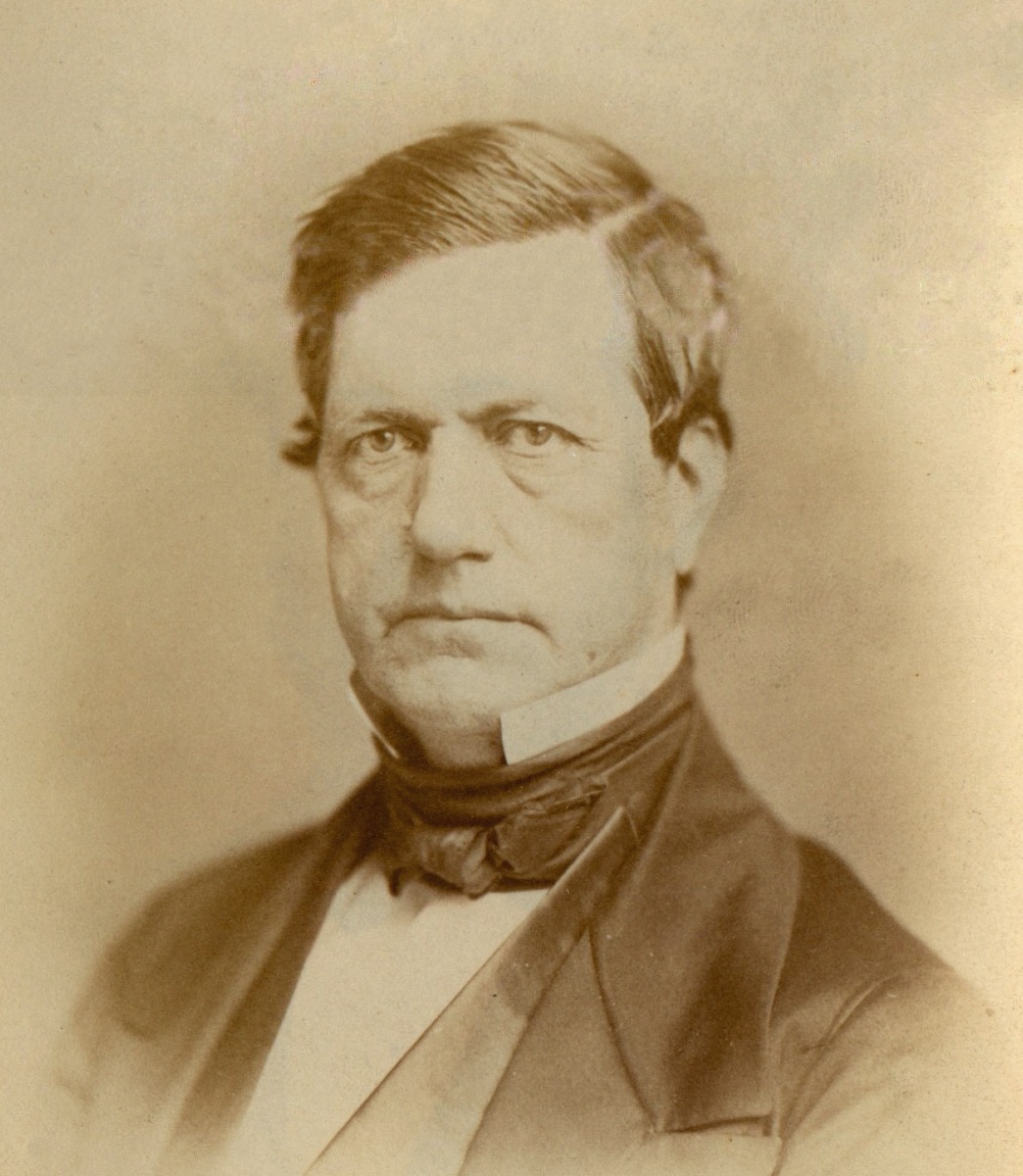

1. John B. Clark – 1861

The first three members were all expelled at the start of the Civil War for the exact reason you’d expect. Missouri congressman John B. Clark owned 160 enslaved people and was a leading voice is the state’s secessionist movement. When he led troops into the Battle of Carthage against Union forces, Congress dismissed him for fighting against the United States.

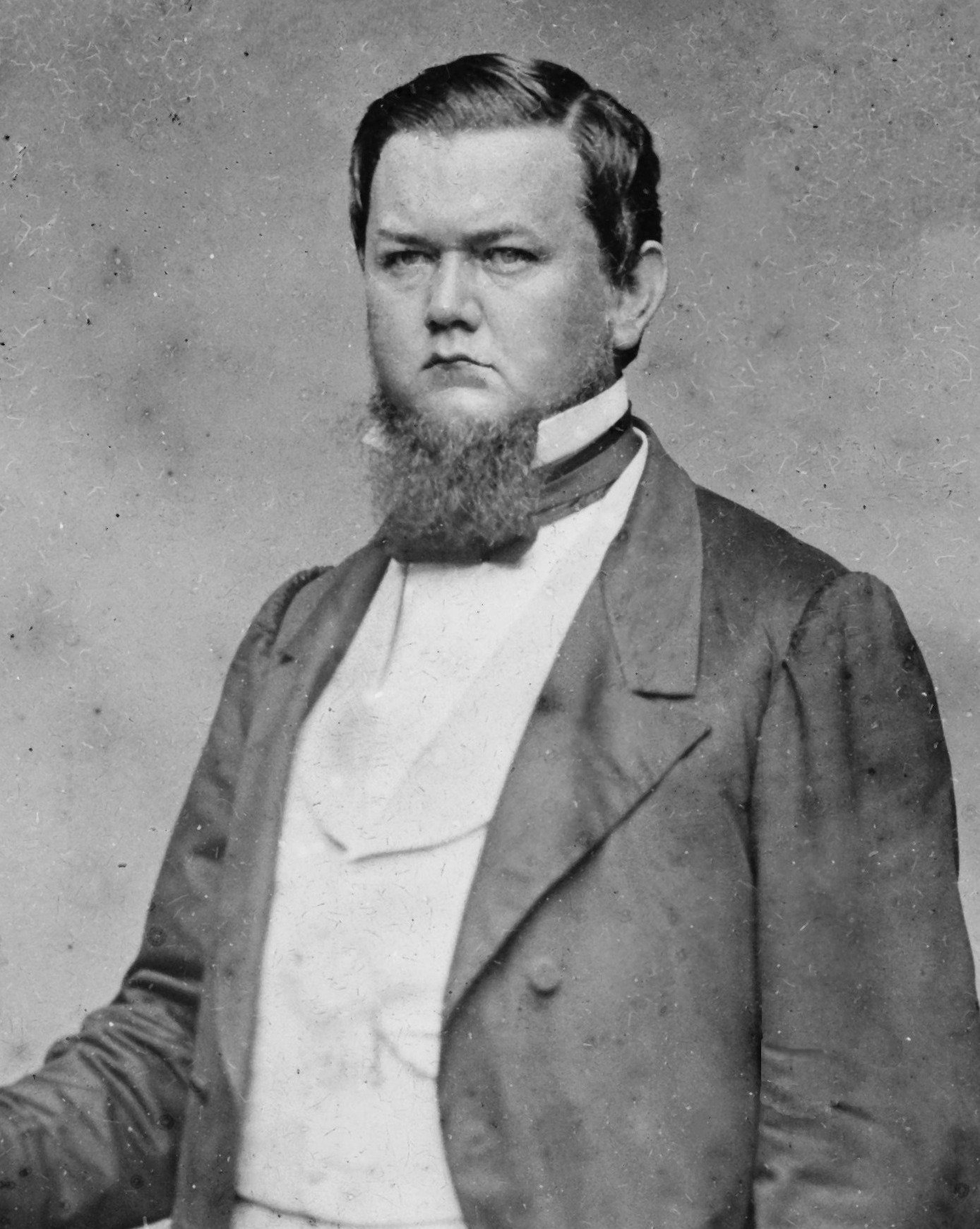

2. John W. Reid – 1861

Like his fellow Missouri congressman, Reid was expelled for taking up arms against the Union in the First Battle of Bull Run—though he did technically resign a few months before his formal expulsion.

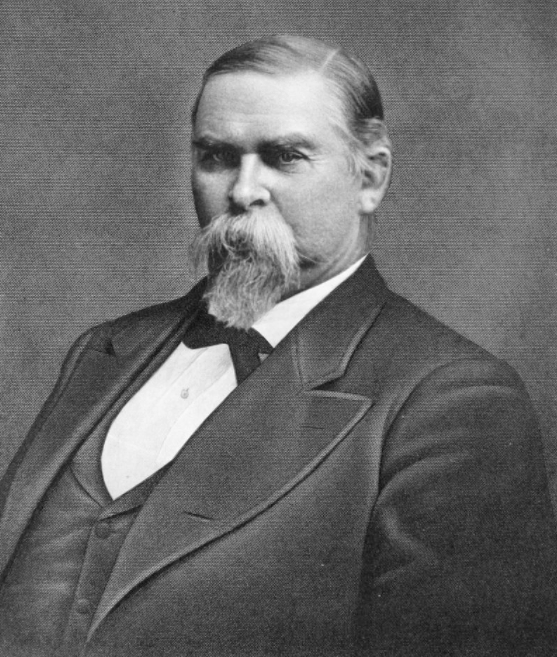

3. Henry C. Burnett – 1861

The third and final member of the House who was expelled on the grounds of fighting against the country they swore an oath to protect, Kentucky representative Burnett was expelled the same day as Reid, December 22, 1861.

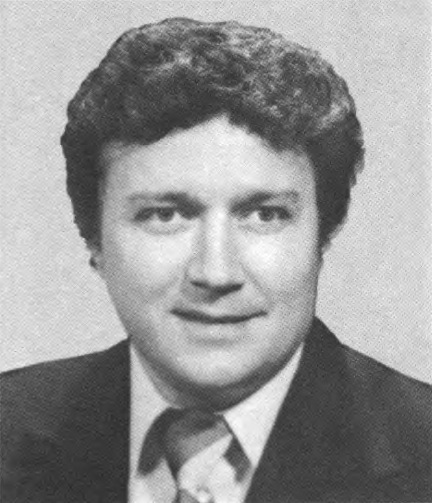

4. Michael “Ozzie” Myers – 1980

At a rooftop party at an Arlington Quality Inn motel in 1979, staff requested that Myers turn the music down. To give you a sense of his character, he allegedly shouted back, “I’m a congressman: we don’t have to be quiet.” In the elevator down from the roof, he got in a fight with a security guard and a 19-year-old cashier, punching and kicking them both. Though his behavior did result in assault and battery charges, he wasn’t a target for expulsion—at least, not yet.

From the late 1970s to early 1980s, the FBI conducted an undercover investigation into corrupt Congressional members. Called ABSCAM, the sting operation involved agents posing as Arab sheikhs and trying to get representatives to accept bribes on camera. (If this all sounds vaguely familiar, that’s because it was the basis of the 2013 film American Hustle). When undercover agents met Myers in a hotel room and asked him to get them a special visa, he replied “money talks in this business and bullshit walks.” He then accepted a $50,000 bribe, the smoking gun that led to his conviction. He was promptly expelled in a vote of 376 to 30.

Decades later, Myers decided it was time for a little bit more crime, and in 2020 was convicted of voter fraud for paying off election workers to cast extra ballots in 2014 and 2018.

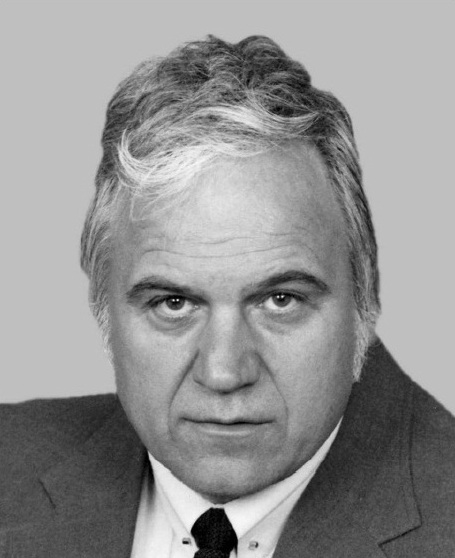

5. James Traficant – 2002

The final expellee, a congressman from Ohio, was quite the character, injecting a catch-phrase borrowed from Star Trek— “beam me up!”—in his speeches. Smock says Traficant was “a likable, funny, if garish guy, who wore the worst hairpieces in the history of humankind. He was also a crook.” The latter descriptor comes from his less-quirky habit of accepting bribes, a behavior that can be traced back all the way to his time as a sheriff:

Smock describes Traficant as a bit of a class clown who was tolerated by his coworkers until he was convicted of a laundry list of crimes—bribery, racketeering, tax evasion, and conspiracy to defraud the United States, all of which resulted in 420 expulsion votes.

Once expelled, Traficant served an eight-year prison sentence. But who says prison has to be the end of a political career? When an election was held to fill his seat, Traficant ran a campaign from behind bars and won 28,045 votes, 15% of the total cast.

6. George Santos?

Even though the House ethics committee has found many problems in Santos’ behavior, some argue that the House should wait until he is convicted of a crime before moving to expel him. Smock disagrees. A vote to expel, he says, is not about criminal guilt, but rather about a member’s fitness to hold the office. Ultimately, Smock says, “the House is the judge of its own members.”