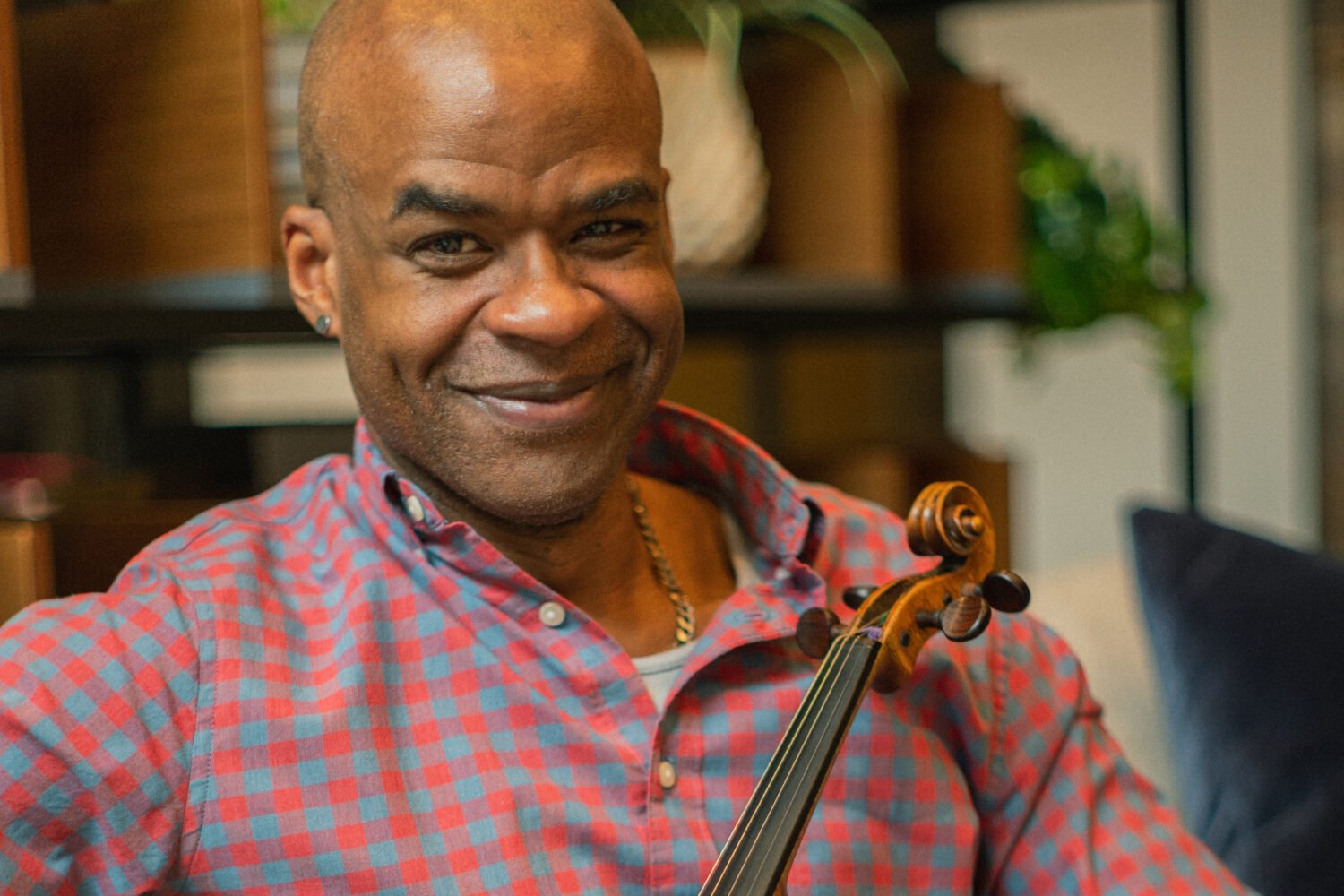

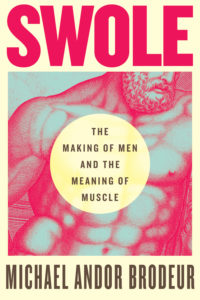

Michael Andor Brodeur is an egghead who looks like a meathead: By trade, he’s the Washington Post’s classical-music critic, but he’s also obsessed with weightlifting. His body is puffed and toned from hours upon hours of raising and lowering heavy chunks of metal at the gym, which he writes about in his new book, Swole. Recently, we met to discuss it in the garden of the Cosmos Club, where Brodeur has been a member since the fall. He wore chunky round glasses and a groomed, triangular mustache. As we drank Aperol spritzes, his arms bulged under his suit.

A blend of memoir and cultural criticism, Swole is a heady book, and a funny one, an exploration of why certain men decide to “get big” and what it means to them when they do. The book is also, as Brodeur told me, an “account of masculinity unraveling”—an attempt to explain why a swath of American men suddenly seem angrier and less secure than they used to be, and why many of those guys are so drawn to working out.

Brodeur got into lifting about 15 years ago, in the aftermath of a bad bike accident. It had the expected result (pumping him up) but also an unexpected one: enabling new kinds of vulnerability with other men. At the gym, Brodeur told me, “the physics of manhood are kind of turned upside down. It’s a level of intimacy that men don’t grant each other pretty much anywhere else. You’re allowed to fail, you’re allowed to touch each other.” Conversations, too, became richer and more vulnerable—men began confessing to struggles with loneliness, addiction, and grief. This led Brodeur to more expansive ideas about masculinity and laid the foundation for Swole.

A gay classical-music critic who loves deadlifting while listening to Richard Strauss, Brodeur is not an archetypical gym guy. He’s 48 and has an MFA in poetry. While he exercises, he’s often drafting articles in his head or listening to a piece of music he’ll be reviewing that night. Back in the ’90s, fresh out of grad school and living in Boston, he supported himself by writing criticism—art, books, music—while playing in a “pretty popular” noise-rock band called the Wicked Farleys. He was, at that time, into experimental music, which led to an interest in classical. The Post hired him in 2020, making him (in his estimate) one of five to ten full-time classical critics left in the US.

For Brodeur, the experience of the gym is “equal parts physical and intellectual.” Lifting makes him think about Beckett and Camus—about pointlessness and repetition and meaninglessness. It’s funny, almost. “I’m someone who knows that death is on the horizon. So what am I doing working so hard to get bigger? Is it so I’ll need a bigger urn?” He called the gym “this room of absurd sculptures, a crazy factory that produces nothing.”

The gym does, however, produce muscles. “Can I touch them?” I asked as we got up from the table.

“No,” he said, and thanked me for my interest in his book.

This article appears in the August 2024 issue of Washingtonian.