The first work visitors will see as they walk up the steps of Mount Pleasant’s Lost Origins Gallery is When Love Spills, a large painting marked by bold planes of reds, yellows, and hot pinks, then punctured by a gash of turquoise. As they continue making their way through the cozy gallery space, visitors will encounter more vivid formations of color—finger-like tendrils of pink, silver metallic zigzags, pulsating yellow brushstrokes—all interspersed with poetry.

These paintings and poems were created by Charles Lenny Lunn, a 34-year-old non-speaking autistic artist from Bethesda. From May 17 through June 8, Lunn’s artwork will be on display at Lost Origins Gallery for his first solo exhibit, “Nonsense & Hopeful Songs.” Alongside the original works, the gallery will sell copies of a monograph—also available on Lunn’s website—with art prints and 15 years’ worth of transcriptions from Lunn’s speech sessions. All proceeds from the exhibit will be donated to charities supporting those with autism.

Lunn was born with apraxia, a rare genetic condition that can be linked with autism. This neurological disorder renders Lunn unable to speak; his brain cannot produce the motor movements required for speech, even though he understands what others around him say. “It is not an intellectual disability. It is a brain-body disconnect,” says Lorie Peters Lauthier, Lunn’s mother. “He hears you, but he might stand there, and you think he’s not listening. But he’s in there, listening.”

In order to communicate, Lunn uses Rapid Prompting Method, or RPM, a method that involves Lunn pointing at individual letters on a letterboard to spell out a message. Everyday expression can be difficult for Lunn, who also has hand tremors resulting from Lyme disease. At a recent appointment with Lisa Mihalich Quinn, one of his communication specialists, I watched as Lunn tapped out a message: “Do you see my hands tremor? It’s awful to rottenly keep trying not to shake now.”

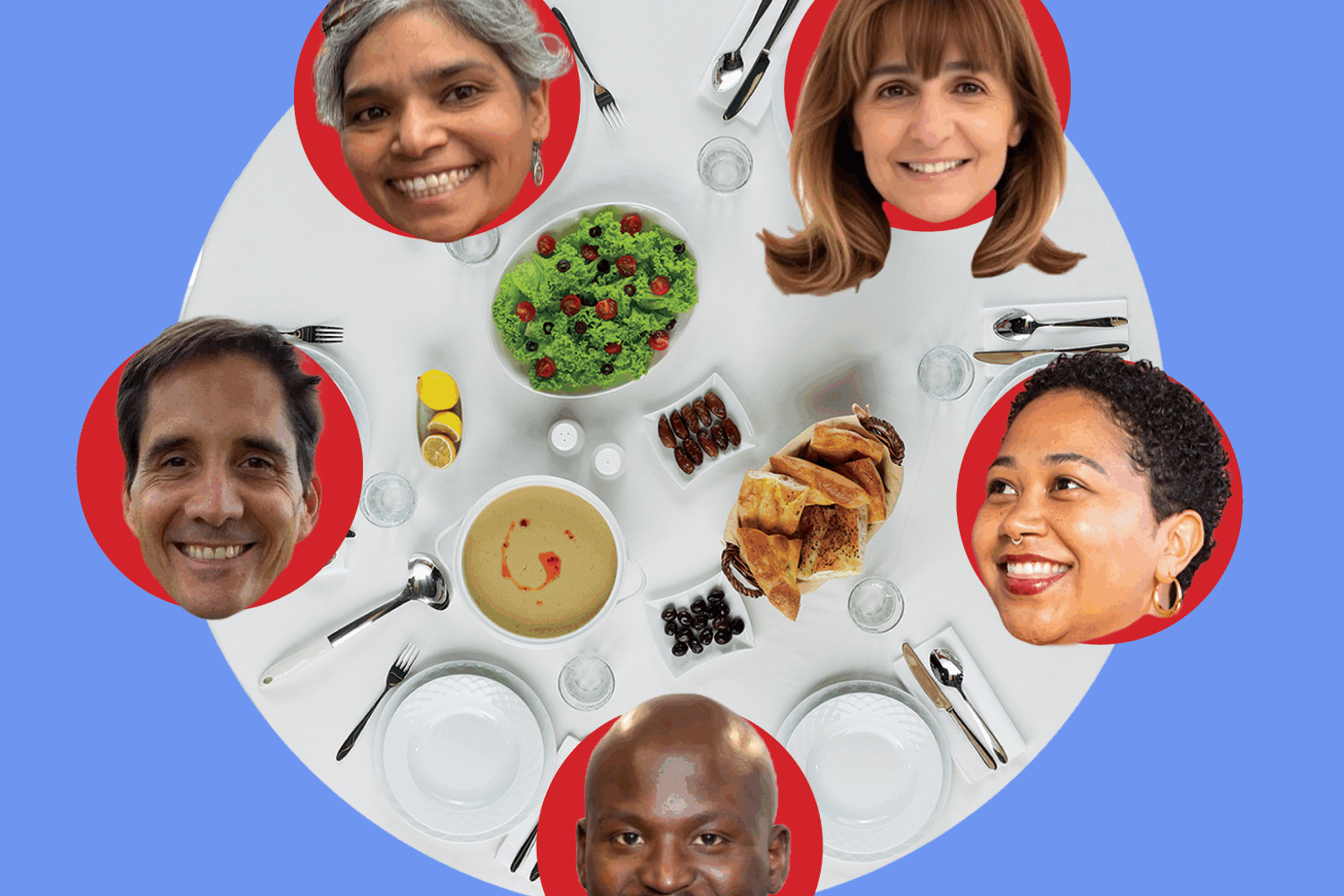

RPM has garnered controversy in recent years as professional associations, including the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association and the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, have discouraged use of the method. These statements are spurred by concerns that the facilitator holding the letterboard may be the one spelling out the message, and not the non-speaking individual. Peters Lauthier is aware of this controversy, but says that Lunn is the sole author of his messages through RPM; even while working with three different communication specialists, Lunn’s voice remains consistent. She also believes that different individuals have different needs, and what matters most is determining the communication method will allow a non-speaking person to best express themselves.

Quinn, who has spent three years working with Lunn and has developed an understanding of his speech and rhythm, also maintains that Lunn’s voice is his own. Lunn is wont to sprinkle foreign words in his sentences: Quinn recounts an incident where Lunn spelled out the word mouton, leaving Quinn confused until she looked it up and realized that it was French for sheep. (Lunn spent several years in France during his childhood.) Likewise, one of the paintings at the exhibit—a moody, blue- and grey-streaked tableau reminiscent of a storm at sea—borrows from French. It’s titled Enfin de Voix: finally, a voice.

Painting and poetry are two vital arenas where Lunn can express his inner world. Lunn paints with a wet-on-wet technique; as he works, the acrylic paints mix together on the canvas and form new colors. In one sequence of paintings, vigorous strokes and vivid reds charge between canvases. “It’s like you’re in a tornado, you’re in a whirlwind,” says Sarah Tanguy, the exhibit’s co-curator.

Lunn’s poetry also shows a witty, sarcastic mind. One poem in the exhibit begins with an entreaty to imagine a world where poets are politicians; it finishes with the wry remark: “Big wars fought over a comma / Best to keep the poets in the cafes.”

Jason Hamacher, owner of Lost Origins Gallery, sees himself and Tanguy as bringing Lunn’s message to a broader public. Hamacher was drawn to Lunn’s artwork and story because of how they “challenge the paradigm of communication,” he says.

For Peters Lauthier, this exhibit is a testament to all her son has achieved. When Lunn was ten months old, doctors said that her son would remain a vegetable his entire life and never make it off all fours. But Peters Lauthier says she constantly championed her son’s competence and capabilities, though there were difficulties along the way. She recounts, for example, the “19 years of silence” she endured before Lunn began first seeing communication specialists. She remembers the excitement she felt as he tapped out his first short phrases on a spelling board; now, she’s watching him put together his first solo art show.

Both mother and son say that they hope the exhibit will push back against harmful narratives about individuals with autism, especially in light of the new administration’s attacks, including Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s disparaging remarks that those with autism would never pay taxes, hold a job, go out on a date, or write a poem.

“Just coming to my show has the tiny potential to challenge assumptions on how non-speaking folks truly don’t sit in silence on the inside,” Lunn shares. “It too often happens that I am judged by the body I inhabit but not my mind.”

One painting in the exhibit—a striking yellow piece titled Firelight—sits next to a poem of Lunn’s. The poem depicts the difficulties of being unable to speak—“Now my lips turn to stone. / My tongue melts.”—but also imagines the beauty of speech: “Tiny specks of my voice fill the cosmos. / My speech glows like the sun.” Much like firelight, communication is a gift that helps illuminate what was once hidden. With this new exhibit, Lunn hopes to bring his inner voice to light for a wider audience.