Jonathan Capehart has had a twisty career, with stopovers as a Pulitzer-winning editorial writer, a staffer on Mike Bloomberg’s first New York City mayoral campaign, a PR professional, and his current twin gigs as a columnist for the Washington Post and the host of his own show on MSNBC. He originally planned his new memoir, Here I Am, as a chronicle of his experiences visiting relatives in the South when he was a young boy, but friends like April Ryan and Joy Reid encouraged him to expand it into a broader look at his life story, including his thoughts about race and sexuality. “The whole point was to be honest and to show people that life is not linear,” Capehart says. “There’s no perfect route, and there are no perfect people.”

We’re around the same age. You write about how fraught it was for you to come out in the ’80s. It made me reflect on what a different time you and I grew up in.

Kids today are coming out younger and younger. When I was a teenager, I had an inkling [I was gay], but had no idea what to call it, what to say. There certainly wasn’t any support structure the way there is now. Progress is slow and incremental, but it happens.

Today, LGBTQ people can get married.

For now.

You also write about being part of the radio station in college, another very Gen-X experience. Is that how you got comfortable being in front of a microphone?

Back then, I was super-shy. There were these a cappella singing groups. Because I was doing a radio show, they were like, “Why don’t you come and introduce us at a big show?” I was super excited, but when I was supposed to go out and introduce them, I was petrified. You couldn’t hear me. The next night, they said, “You know what, Jonathan? We’re going to have someone else do it.”

Even to this day, I can sit in a television studio and talk to a camera, but to go to a venue and actually see faces in the audience, and the person who’s bored, the person who’s mad, the person who thinks you’re full of shit, the person who’s looking at their phone, the person who’s asleep—that’s nerve-racking. It also makes me empathize with the person for whom [an appearance on my MSNBC show] might be their first time on television and they’re nervous. I’ll always ask, “Is this your first time doing television? You’re going to be fine. Just talk to me.”

You’ve laid a lot of your life out in this book, from the time you sent a friend to rescue your porn stash from your mom’s house to your feelings of not fitting in with either white or Black people at times. Was it hard to expose your vulnerabilities?

When I was writing, I was following the north stars provided by Katharine Graham and Charles Blow. When they sat down to write their memoirs, there was no overt airbrushing of painful things or failures. To me as a reader, but also just as a human being, to know that someone of such stature could be so real and vulnerable said to me that if I ever got to the point where someone wanted to hear my story, I would do the same thing. Why write the book if it’s going to be sugarcoated? Honestly, one of the chapters that was—I’m not going to say therapeutic, I’m not going to say fun, but was probably the most important is the one whose title is redacted.

That’s the chapter called “F****** S***,” about your detour into PR after you left Bloomberg News. That didn’t go well–you hated it. Now you advise people not to take a job just for money.

I chronicle five years of catching hell, personally and professionally. These were not fun times when I was living them; they were incredibly painful. But I’m on the other side now. I hope that when people read this book, they see a bit of themselves in that, because everyone goes through failure. The chief way I was able to get through it was to suddenly reacquaint myself with my north star: journalism.

You write that you left the Post editorial board because of your interactions with the board’s former deputy boss, who you felt ignored your concerns about the wording of an editorial about voting rights in Georgia. You say it was a “private humiliation” that emphasized how alone you felt on the board as the only Black, gay member.

The disagreement was over more than wording. It was a policy point.

What’s your status with the Post now? Owner Jeff Bezos wants its opinion section to focus on “personal liberties and free markets.” Where does that leave you?

I’m still in the opinion section. I only left the board. Once [opinion editor] David Shipley announced he was leaving, I thought: I don’t know where this leaves me. [But] last week, I was going to get my hair cut and I went past Black Lives Matter Plaza and heard the jackhammers. And then it hit me: Oh, my God, they’re doing it now. They’re tearing it up. It just hurt. And so I walked back to the office and I thought: That is my column. This is what I’m going to write. I filed the piece. It went to my editor. Went to another editor. Went to the copy desk. Went online. And nothing.

When I saw “personal liberty,” I was like, what does that mean for those of us who write about race? And right now the answer is nothing: Keep doing what you’re doing—that’s what Shipley told us before he left. And so far, so good for me right now.

I remember that in 2020 you went to Black Lives Matter Plaza with Congressman John Lewis for a column and TV segment.

It was just incredible to see this man, who had his skull cracked at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, on the top of a building looking down over a place that had been the site of massive protests because of the murder of George Floyd.

A lot of people thought all of the progress that had been made was being reversed by the man in the White House at the time. And yet [Lewis] still had a very optimistic view of where we could go. He was so energized and excited by the young people who had taken to the streets. When I think back on that moment—as tough as it is now, infinitely worse than it was in 2020—he’s sort of like a beacon. Because as bad as things are, he went through worse.

Yeah, I was going to ask you how optimistic you feel nowadays.

It is hard to watch what’s happening, on so many levels. But when it comes to the efforts to erase American history—I’m not going to call it Black history—it’s shameful. I would like to think there are enough people in this country who will hold the line on who we are as Americans and weather this storm as best they can, as best we can.

The administration keeps saying the only reason we pay any attention to that history is because of some sort of DEI effort. And then they took Jackie Robinson’s story off of the Pentagon website.

Right. And that’s a big name that people know. Elizabeth Alexander, the poet—her father, Clifford Alexander, was the first Black Secretary of the Army. Cora Masters Barry—her father was the first Black US Marine. You can focus on Jackie Robinson. But don’t forget that there are so many other people who did incredible things. It’s great that they restored Jackie Robinson’s page. Last I heard, they haven’t restored the others.

“I understand the symbolism of Black Lives Matter Plaza. But for me, when I’m looking at the mayor, it’s like, yes, please do what you can to save the city.”

You mentioned the dismantling of Black Lives Matter Plaza. What do you make of Mayor Bowser agreeing to do that?

The mayor is like, I need to [prevent] that billion dollars in cuts that they’re looking at, not to mention threats to home rule. And so if that means Black Lives Matter Plaza has to go away, what do you want? The monument? Or for services to continue? That’s kind of hard to hear for a lot of people. I understand the symbolism of Black Lives Matter Plaza. But for me, when I’m looking at the mayor, it’s like, yes, please do what you can to save the city.

We’re not in normal times. I had Mayor Bowser on my show. People were giving her hell over Black Lives Matter Plaza and capitulating, blah, blah, blah. But I wanted to have her on because I needed the viewers to understand that unlike any governor in this country, her fate as mayor, the city’s fate, the District’s fate, rests in the hands of the President and Congress. Fine, be angry about Black Lives Matter Plaza. Totally get it. But please appreciate the bind she is in.

A lot of institutions are in the same boat. Media organizations, law firms . . . .

I don’t want to call out any particular media organization, but let’s just say if one were to decide to settle a lawsuit rather than go into court, I could understand why, especially when you look back to what happened to Fox [which paid nearly $800 million to settle a defamation lawsuit]. When they were about to go to court, all the information that went out—the text messages and the emails and things—if you’re a news organization, do you want that to happen to you? You know, fight, don’t give in. But then on the other hand, it’s how much damage are you willing to take? A principled stand, great. But then you lose half your newsroom. None of this is easy.

Jonathan Capehart has had a twisty career, with stopovers as a Pulitzer-winning editorial writer, a staffer on Mike Bloomberg’s first New York City mayoral campaign, a PR professional, and his current twin gigs as a columnist for the Washington Post and the host of his own show on MSNBC. He originally planned his new memoir, Here I Am, as a chronicle of his experiences visiting relatives in the South when he was a young boy, but friends like April Ryan and Joy Reid encouraged him to expand it into a broader look at his life story, including his thoughts about race and sexuality. “The whole point was to be honest and to show people that life is not linear,” Capehart says. “There’s no perfect route, and there are no perfect people.”

We’re around the same age. You write about how fraught it was for you to come out in the ’80s. It made me reflect on what a different time you and I grew up in.

Kids today are coming out younger and younger. When I was a teenager, I had an inkling [I was gay], but had no idea what to call it, what to say. There certainly wasn’t any support structure the way there is now. Progress is slow and incremental, but it happens.

Today, LGBTQ people can get married.

For now.

You also write about being part of the radio station in college, another very Gen-X experience. Is that how you got comfortable being in front of a microphone?

Back then, I was super-shy. There were these a cappella singing groups. Because I was doing a radio show, they were like, “Why don’t you come and introduce us at a big show?” I was super excited, but when I was supposed to go out and introduce them, I was petrified. You couldn’t hear me. The next night, they said, “You know what, Jonathan? We’re going to have someone else do it.”

Even to this day, I can sit in a television studio and talk to a camera, but to go to a venue and actually see faces in the audience, and the person who’s bored, the person who’s mad, the person who thinks you’re full of shit, the person who’s looking at their phone, the person who’s asleep—that’s nerve-racking. It also makes me empathize with the person for whom [an appearance on my MSNBC show] might be their first time on television and they’re nervous. I’ll always ask, “Is this your first time doing television? You’re going to be fine. Just talk to me.”

You’ve laid a lot of your life out in this book, from the time you sent a friend to rescue your porn stash from your mom’s house to your feelings of not fitting in with either white or Black people at times. Was it hard to expose your vulnerabilities?

When I was writing, I was following the north stars provided by Katharine Graham and Charles Blow. When they sat down to write their memoirs, there was no overt airbrushing of painful things or failures. To me as a reader, but also just as a human being, to know that someone of such stature could be so real and vulnerable said to me that if I ever got to the point where someone wanted to hear my story, I would do the same thing. Why write the book if it’s going to be sugarcoated? Honestly, one of the chapters that was—I’m not going to say therapeutic, I’m not going to say fun, but was probably the most important is the one whose title is redacted.

That’s the chapter called “F****** S***,” about your detour into PR after you left Bloomberg News. That didn’t go well–you hated it. Now you advise people not to take a job just for money.

I chronicle five years of catching hell, personally and professionally. These were not fun times when I was living them; they were incredibly painful. But I’m on the other side now. I hope that when people read this book, they see a bit of themselves in that, because everyone goes through failure. The chief way I was able to get through it was to suddenly reacquaint myself with my north star: journalism.

You write that you left the Post editorial board because of your interactions with the board’s former deputy boss, who you felt ignored your concerns about the wording of an editorial about voting rights in Georgia. You say it was a “private humiliation” that emphasized how alone you felt on the board as the only Black, gay member.

The disagreement was over more than wording. It was a policy point.

What’s your status with the Post now? Owner Jeff Bezos wants its opinion section to focus on “personal liberties and free markets.” Where does that leave you?

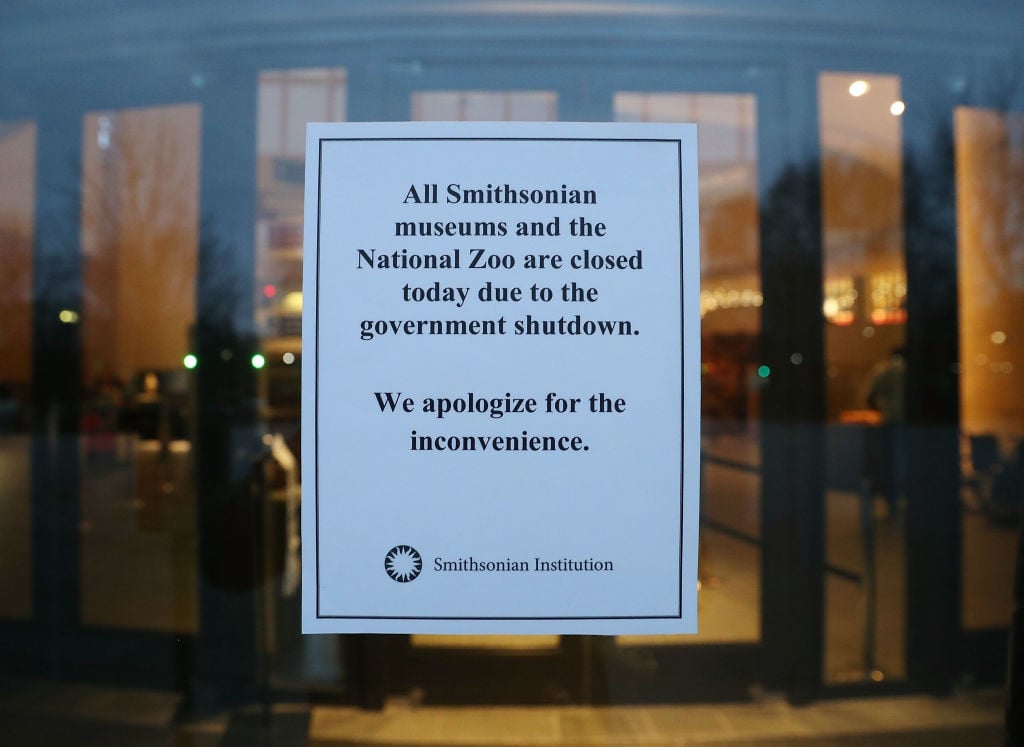

I’m still in the opinion section. I only left the board. Once [opinion editor] David Shipley announced he was leaving, I thought: I don’t know where this leaves me. [But] last week, I was going to get my hair cut and I went past Black Lives Matter Plaza and heard the jackhammers. And then it hit me: Oh, my God, they’re doing it now. They’re tearing it up. It just hurt. And so I walked back to the office and I thought: That is my column. This is what I’m going to write. I filed the piece. It went to my editor. Went to another editor. Went to the copy desk. Went online. And nothing.

When I saw “personal liberty,” I was like, what does that mean for those of us who write about race? And right now the answer is nothing: Keep doing what you’re doing—that’s what Shipley told us before he left. And so far, so good for me right now.

I remember that in 2020 you went to Black Lives Matter Plaza with Congressman John Lewis for a column and TV segment.

It was just incredible to see this man, who had his skull cracked at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, on the top of a building looking down over a place that had been the site of massive protests because of the murder of George Floyd.

A lot of people thought all of the progress that had been made was being reversed by the man in the White House at the time. And yet [Lewis] still had a very optimistic view of where we could go. He was so energized and excited by the young people who had taken to the streets. When I think back on that moment—as tough as it is now, infinitely worse than it was in 2020—he’s sort of like a beacon. Because as bad as things are, he went through worse.

Yeah, I was going to ask you how optimistic you feel nowadays.

It is hard to watch what’s happening, on so many levels. But when it comes to the efforts to erase American history—I’m not going to call it Black history—it’s shameful. I would like to think there are enough people in this country who will hold the line on who we are as Americans and weather this storm as best they can, as best we can.

The administration keeps saying the only reason we pay any attention to that history is because of some sort of DEI effort. And then they took Jackie Robinson’s story off of the Pentagon website.

Right. And that’s a big name that people know. Elizabeth Alexander, the poet—her father, Clifford Alexander, was the first Black Secretary of the Army. Cora Masters Barry—her father was the first Black US Marine. You can focus on Jackie Robinson. But don’t forget that there are so many other people who did incredible things. It’s great that they restored Jackie Robinson’s page. Last I heard, they haven’t restored the others.

I understand the symbolism of Black Lives Matter Plaza. But for me, when I’m looking at the mayor, it’s like, yes, please do what you can to save the city.

You mentioned the dismantling of Black Lives Matter Plaza. What do you make of Mayor Bowser agreeing to do that?

The mayor is like, I need to [prevent] that billion dollars in cuts that they’re looking at, not to mention threats to home rule. And so if that means Black Lives Matter Plaza has to go away, what do you want? The monument? Or for services to continue? That’s kind of hard to hear for a lot of people. I understand the symbolism of Black Lives Matter Plaza. But for me, when I’m looking at the mayor, it’s like, yes, please do what you can to save the city.

We’re not in normal times. I had Mayor Bowser on my show. People were giving her hell over Black Lives Matter Plaza and capitulating, blah, blah, blah. But I wanted to have her on because I needed the viewers to understand that unlike any governor in this country, her fate as mayor, the city’s fate, the District’s fate, rests in the hands of the President and Congress. Fine, be angry about Black Lives Matter Plaza. Totally get it. But please appreciate the bind she is in.

A lot of institutions are in the same boat. Media organizations, law firms . . . .

I don’t want to call out any particular media organization, but let’s just say if one were to decide to settle a lawsuit rather than go into court, I could understand why, especially when you look back to what happened to Fox [which paid nearly $800 million to settle a defamation lawsuit]. When they were about to go to court, all the information that went out—the text messages and the emails and things—if you’re a news organization, do you want that to happen to you? You know, fight, don’t give in. But then on the other hand, it’s how much damage are you willing to take? A principled stand, great. But then you lose half your newsroom. None of this is easy.

This article appears in the May 2025 issue of Washingtonian.