n April 13, 2024, a woman we’ll call Rachel stepped out of her home in Northeast DC following a heated argument with her soon-to-be-ex-husband. A brisk walk through the neighborhood, she thought, would be just the thing to alleviate the stress of her contentious divorce. And sure enough, after walking for about 45 minutes on that spring afternoon, Rachel felt calm, grounded, and ready to return home. But as she turned back onto H Street, just north of Union Station, a team of Metropolitan Police Department officers appeared out of nowhere.

Surrounding Rachel, the officers placed her in handcuffs and—without explanation—secured her in the back of a squad car. “The first thing I thought, she recalls, was ‘Okay, my spouse must have called the police.’ ”

Her hunch was correct. Around the time of their argument, according to a lawsuit she would later join, her husband had reported to police that Rachel, who he claimed had been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, was threatening to kill herself. These allegations, Rachel insists, were untrue. She’d never been diagnosed with any form of mental illness, and while she had made a regrettable comment to her husband in the heat of their argument—“[It] feels like you want me to jump off a bridge”—the remark was certainly not intended to express suicidal ideation.

She was a confused mother of two, simply trying to get home to her young children. Her troubles were just starting.

Nevertheless, on the basis of her husband’s claims, police were now transporting Rachel to the city’s Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program (CPEP) in Southeast DC, where those in mental-health crisis are evaluated and, if necessary, processed into facilities that can provide longer-term care. Upon entering the squat one-story building, next to the DC Jail, Rachel says, she was led into a room with padded walls and a flickering fluorescent light. Eventually, a man with a clipboard arrived, offering neither his name nor his role at the facility.

“What’s going on?” the man said.

As Rachel began to explain the conflict with her husband and the misunderstanding that preceded her detainment, the man put his hand up.

“I’m going to stop you right there,” he said. “It sounds to me like you’re only talking about other people.” The man paused, and Rachel resumed talking. “I think that you need some time to sit with your emotions,” the man said.

Over the next few hours, Rachel says, she insisted to any staff member who would listen that she was not in a state of psychiatric crisis and that she’d never considered harming herself. Yet despite not conducting a proper medical examination, her lawsuit states, officials moved to have her involuntarily detained at CPEP. (Asked about this claim by Washingtonian, city officials did not comment.) The next morning, Rachel was loaded onto a gurney, her arms and legs strapped to the safety rails, and driven in an ambulance to the psychiatric facility where she was to be treated. “I had no idea what was happening, where I was going, and if I was going to be safe,” she says.

Some 45 minutes later, Rachel arrived at the Psychiatric Institute of Washington (PIW), a 152-bed private facility in Northwest DC where the bulk of the city’s involuntary commitments are sent. She entered the hospital as a confused mother of two, simply trying to get home to her young children. Her troubles were just starting.

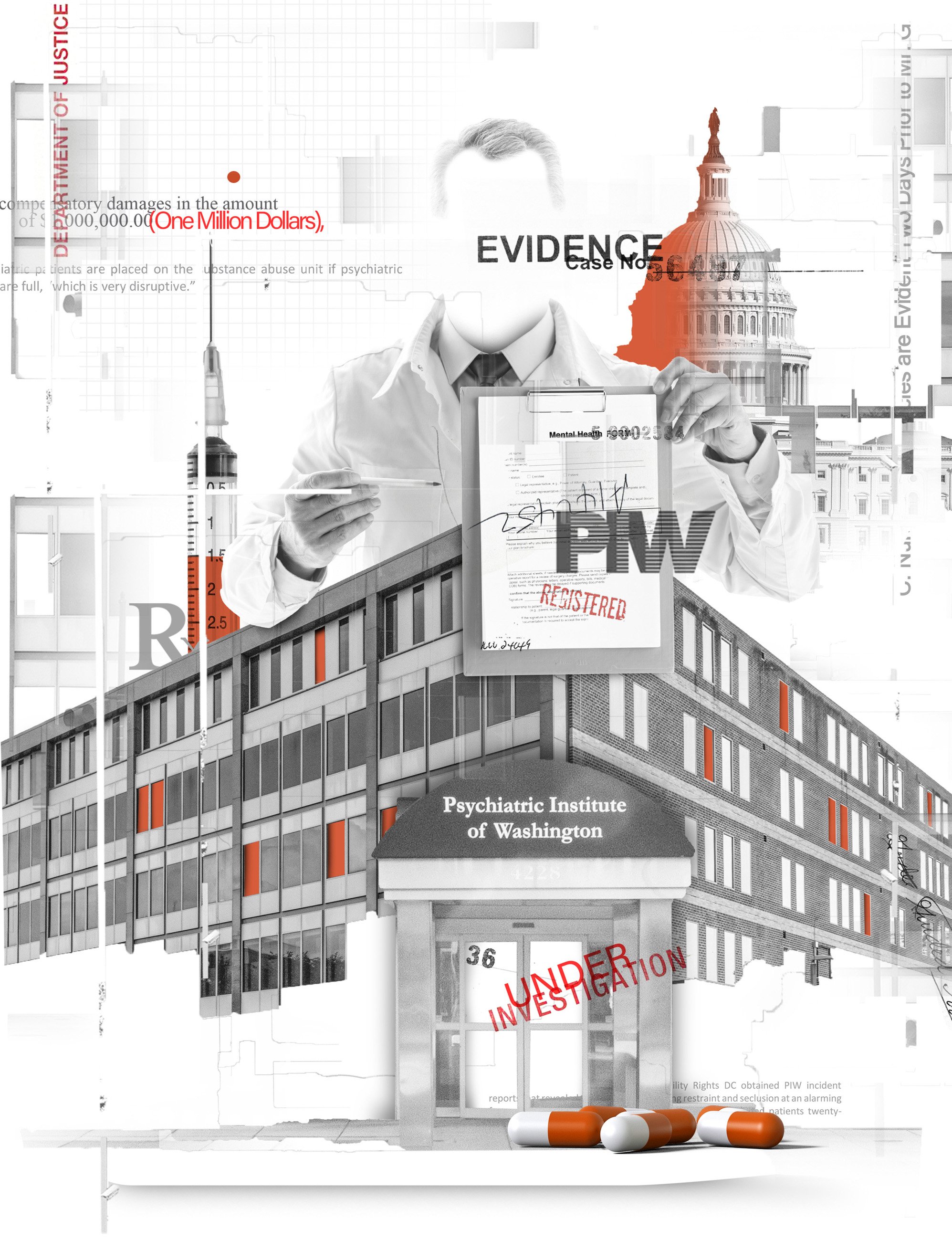

Opened in 1967, PIW treats adolescents and adults struggling with substance abuse or psychiatric distress. But in recent years, the facility has faced alarming allegations of patient violence, staff misconduct, and systemic dysfunction. The watchdog group Disability Rights DC, the federally designated advocate for people with disabilities in the District, has found in a series of reports that those admitted to PIW are under near-constant threat of patient-on-patient attacks or sexual assault. Recent lawsuits have accused PIW of negligence in the rape of one patient and the death of another. In 2023, a PIW staff member was arrested and charged with sexually abusing a patient in his care. The following year, a group of teenage patients attacked an employee, took their badge, and escaped from the hospital. Last December, a ten-year-old patient who’d been admitted to PIW for depression reported being sexually abused at the facility.

One former health aide tells Washingtonian the violence and disorder inside PIW were so terrifying that she began developing nosebleeds before her shifts. “I mean, this place is actually trauma-inducing,” she says.

This story is based on interviews with a dozen former patients and workers, nearly all of whom requested anonymity to speak candidly. According to some former staffers, the dangerous conditions inside PIW reflect the perceived priorities of its corporate parent, Universal Health Services. The Pennsylvania-based, for-profit conglomerate acquired PIW in 2014. Today, UHS controls more than 300 such facilities around the globe, caring for nearly 4 million patients annually and raking in enough revenue—$15.8 billion in 2024—to make the Fortune 500 list. But the behavioral-health colossus has faced troubling claims of abuse and neglect.

In 2020, UHS reached a $122 million settlement with the Department of Justice to resolve allegations that it had failed to provide adequate training to staff, therapy for patients, and supervision of its employees. Three years later, a South Carolina news station obtained complaints about a UHS-owned youth-treatment facility, “alleging there are bugs, abuse, dangerously low staffing levels, violent fights and blood and vomit smeared throughout the building.” In March 2024, an Illinois jury awarded $535 million in damages to a 13-year-old ex-patient whose mother had sued a nearby UHS-owned facility for negligence after another patient there raped the young girl.

Under UHS’s ownership, according to former staff, PIW routinely sacrifices the well-being of those in its care in order to admit as many patients as possible, bill for whatever services insurance will cover, and deliver financial returns to its shareholders. “It’s almost just like a patient mill,” says one source who spent time in the facility.

“I knew that I was not safe. I was in 100 percent survival mode.”

During her four days trapped inside PIW, Rachel was appalled by what she describes as unsafe conditions and poor quality of care. She later came to believe that her traumatic stay was not the result of honest mistakes or bureaucratic snafus but rather the consequence of a giant corporation perpetually hunting more customers.

In February of this year, Rachel became an unidentified plaintiff in a class-action civil lawsuit against PIW and UHS filed in federal court in DC. Seeking unspecified damages, the lawsuit alleges that the facility and its corporate owner violated the DC Human Rights Act, the Americans With Disabilities Act, and other laws while intentionally inflicting emotional distress. UHS, the suit further claims, “has employed and continues to employ a brazen corporate strategy of involuntarily hospitalizing PIW patients without cause or indication [and] prolonging patients’ hospitalizations unnecessarily and without cause or indication. . . . These illegal actions have been and continue to be driven by a focus on profit at the expense of patient care, safety, and treatment.”

“It’s not a patient-centric culture, despite the fact that they render healthcare services,” plaintiff’s attorney Drew LaFramboise says of UHS. “It’s a shareholder-centric culture.”

K. Nichole Nesbitt, a lawyer for PIW, told Washingtonian in an email that the institution “denies the allegations in the lawsuit and the conclusions of the DC Disability Rights Report and will defend itself vigorously against these claims and matters in court.” The safety and well-being of patients and staff, PIW said in a statement provided by Nesbitt, is its “highest priority,” and the institution “does not discount or disregard any ideas or suggestions” to address safety concerns “for financial reasons.”

PIW declined to comment on many of the additional claims about it contained in this story, citing the privacy restrictions of the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, ongoing litigation, and Washingtonian’s use of anonymous sources. “It is difficult to address the specifics of such claims without being able to understand the full context,” PIW said.

A senior director for corporate public relations at UHS did not provide Washingtonian with a response to emails seeking comment on the class-action lawsuit and the additional claims about UHS contained in this article.

Once the ambulance pulled up to PIW, an employee escorted Rachel up the elevator and into her unit. Inside, Rachel says, she found agitated patients quarreling with staff as shrieks of distress echoed through the halls. Almost immediately, one patient began screaming about the room Rachel had been assigned to, insisting that it actually belonged to him. Meanwhile, a towering, heavyset female patient came within inches of Rachel’s face, only to begin caressing Rachel’s hair and complimenting her on her appearance. Patients used encounters like this, Rachel says, to test how new arrivals would react.

“It was sort of like entering jail, where people are trying to figure out if you can be bullied,” she says.

Rachel was desperate to prove she was not in a psychiatric crisis and could therefore be released and return home to her children. But for now, other priorities were more urgent. “I knew that I was not safe,” she says. “I was in 100 percent survival mode.”

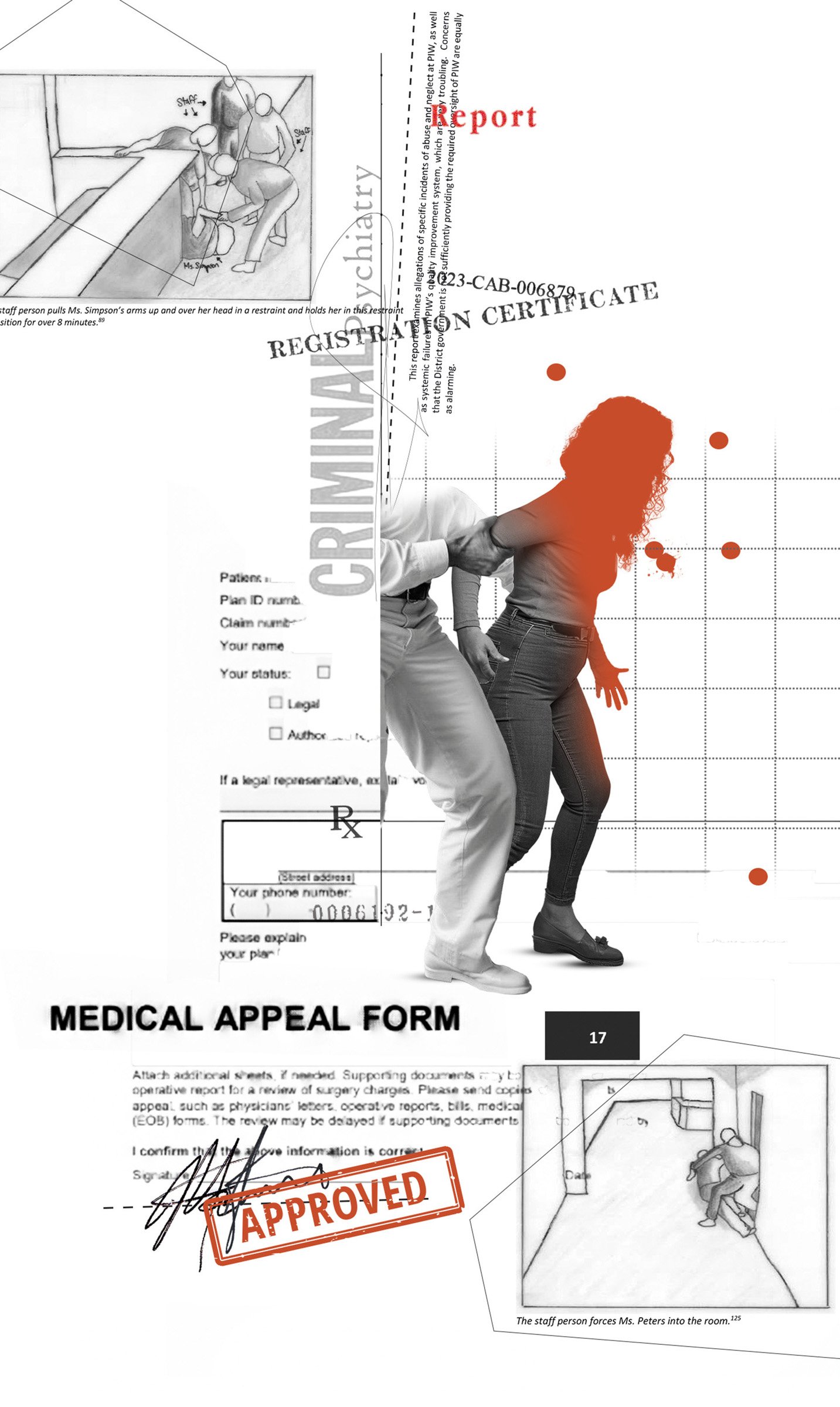

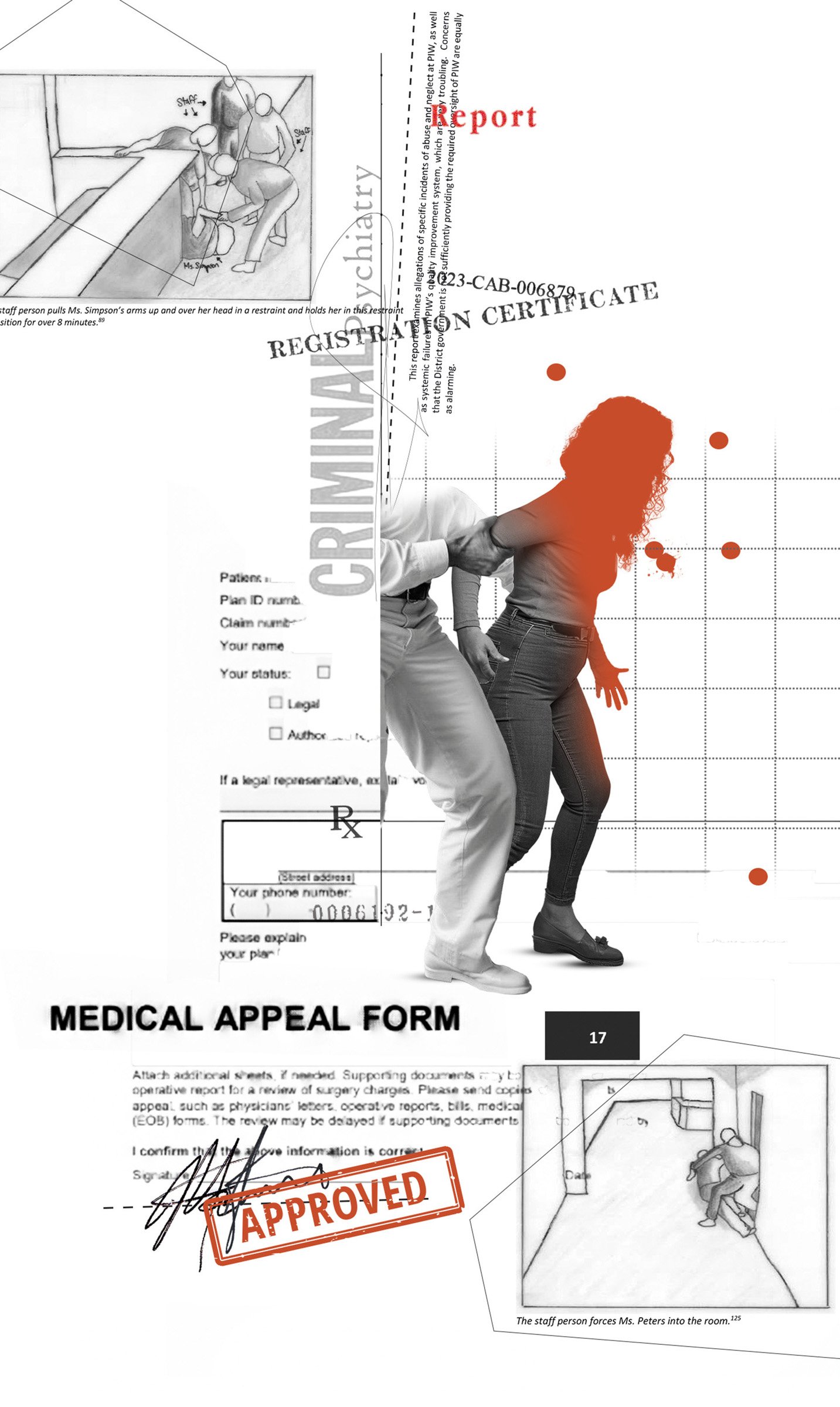

Former staff say the violence at PIW is alarming and routine. During 2023 alone, according to Disability Rights DC, patient-on-patient attacks resulted in broken bones, human bite marks, and emergency-room visits. “It looks like she was attacked by an animal,” a PIW staff member said of the victim of one such assault, in a 2024 incident report obtained by the watchdog group.

Employees are targets as well. Former employees tell Washingtonian that one staff member had a door repeatedly closed on his head by a patient, and another had urine thrown at her. When things got really bad, one former PIW employee told Disability Rights DC, units descended into rioting.

The environment was so explosive, former patients say, because PIW failed to deliver the resources necessary to properly care for its already challenging patient population. On any given day, according to former employees, the facility contained a volatile blend of locals in mental-health crisis, addicts coming down off drugs, and people experiencing homelessness. “You’re mixing, like, DC gangsters with flamboyant guys who are in there because they’ve done too much meth,” a former staffer says.

Conditions in the facility aggravated patients and amplified tensions. According to the class-action lawsuit and what former staff told Washingtonian, the units often stank of urine and feces. According to interviews with former staffers and a 2024 employee complaint obtained by Disability Rights DC, the temperatures inside the building got so cold that ice sometimes formed on the windows. And according to the class-action lawsuit, staff members told patients that the toilet had to be flushed three times to get hot water in the showers. Lack of structured activities and outdoor recreation meant patients passed most of their time milling aimlessly around the units, stewing in boredom and restlessness. Frequent shortages of basic necessities turned latent discontent into outright conflict. According to what former staff told Washingtonian and an employee complaint obtained by Disability Rights DC, PIW regularly failed to provide enough food to its patients—a deficiency all the more distressing because the medications prescribed to many patients often increased their appetites. Nurses and aides regularly went out of pocket to purchase snacks for hungry patients, but they couldn’t keep everyone sated. “Food was one of the biggest things that patients would fight about,” says one former nurse, “because we wouldn’t have enough of one kind or another.” (PIW denied failing to provide enough food for its patients.)

PIW’s staff was unable to prevent the escalation of violence. This was partially due to what former staffers describe as a chronic worker shortage, which often forced solitary employees to manage unreasonably large groups of patients. A city-government review of the facility’s staffing levels over a 15-day period in May 2022 found that many—and sometimes all—of its units were without requisite staff on all 15 of those days. Last year, former PIW nurse Elizabeth Deal testified before the DC Council that staffing levels at the facility—one nurse and one or two technicians for 18 to 21 patients—were insufficient. “I once worked a unit by myself with 19 patients,” another former mental-health aide told Washingtonian.

Former staffers say the quality of individual workers was also a factor. Many employees chose to work at PIW out of a genuine desire to help patients in distress—but others, according to ex-staff, were drawn by the competitive pay and lacked the passion that this difficult field demands. One former employee recalls finding a night nurse fast asleep while on duty: “She was wearing a neck pillow, propped her feet up, had blinders on and everything.” Other staff members were so uncommitted to PIW’s mission, a former employee says, that they questioned why drug addicts or the mentally ill would be treated at all.

“Literally, some of them are like, ‘Oh, [that patient] just needs to pray or find Jesus,’ ” the former employee recalls.

In November 2023, former patient Leon Allen sued PIW, alleging he’d suffered rib and hip fractures when he was body-slammed by a staff member during a dispute over telephone access. The case was later dismissed. In December 2023, DC police arrested a 44-year-old PIW staff member, Jerry Mack, and charged him with first-degree sexual abuse of an adolescent patient in his care. Mack subsequently pleaded guilty to one count of first-degree sexual abuse of a ward and was sentenced to three years in prison.

Last December, a different former female patient, Ambriel Rose Veldkamp, sued PIW for negligence, claiming that it failed to prevent her from being raped by a man at the facility in 2021. In her lawsuit, Veldkamp said two other men may have watched or participated in the assault as well, though she can’t say for sure because the medication prescribed to her may have caused her to black out. PIW has denied responsibility for the incident in court documents, and the lawsuit is ongoing.

In December 2024, according to an investigative survey conducted by the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, a ten-year-old patient who’d been admitted to PIW for depression reported being sexually abused by a 15-year-old patient. According to the report, the ten-year-old told PIW staff that the older patient “came into my room and touched my [genitalia] and my private area.” In its investigation, CMS found that PIW had violated federal regulations designed to prevent sexual-abuse incidents like this in two ways: first, by permitting patients under age 18 and with an age difference of more than three years to room together; second, by failing to keep bedroom doors locked when not in use. In addition, according to the report, PIW staff did not alert DC’s Child and Family Services Agency to the incident, even though they’re required by law to do so.

PIW declined to comment on Mack’s arrest, Allen’s lawsuit, or Veldkamp’s lawsuit, and did not provide comment on the sexual-abuse investigation involving the ten-year-old patient. UHS did not provide comment.

During her first few hours at PIW, Rachel says, she learned to avoid conflict by disappearing into a corner or reading alone on her bed. Although physically safe, she remained disoriented and confused. She had no idea what rights she possessed, how long she would be stuck there, or what she could do to prove this was all a mistake. Most of the staff, she felt, had no interest in helping. “It was just a wall of silence and random people who didn’t introduce themselves,” she recalls.

Around 11:30 am on her first day, however, she met with a psychiatrist, Dr. Menachem Groden. Unlike other staff, Rachel says, he was patient and engaged, listening carefully as she explained her acrimonious divorce and the misunderstanding with her husband. In his notes of their conversation, portions of which are contained in the class-action lawsuit, Dr. Groden described Rachel as “calm and cooperative” with a “linear and logical” thought process and “good” judgment. As their discussion drew to a close, Rachel tells Washingtonian, the psychiatrist made a remark: “I’m so sorry this is happening. You shouldn’t be here.”

Dr. Groden didn’t have discharge privileges—and because it was a Sunday, he wouldn’t have been able to release her even if he did. Instead, Rachel says, he instructed her to find PIW’s court liaison the following morning and request a probable-cause hearing to challenge the basis of her detainment.

She had no idea what rights she possessed, how long she would be stuck there, or what she could do to prove this was all a mistake.

At 9 am sharp the next day, Rachel says, she planted herself in a chair by a staff desk, eager to meet the court liaison. Hours went by. Rachel says she asked a staff member for assistance, but the employee didn’t know who the court liaison was. The phones in the unit were broken. A nurse dialed PIW’s patient advocate on her mobile phone and handed it to Rachel. The patient advocate, however, was on vacation.

At around 4 pm, after roughly seven hours of waiting, Rachel says she flagged down a female staff member and explained she was looking for the court liaison.

“Oh,” the woman replied, “I’m the court liaison.”

“I’m trying to [request] a probable-cause hearing,” Rachel explained.

The liaison broke the bad news. “The courts are closed now,” she said, “and tomorrow is a court holiday [for Emancipation Day].”

The treatment provided, according to former employees and a lawsuit, ranged from lackluster to nearly nonexistent.

In spite of Dr. Groden’s findings, Rachel remained trapped in the mental hospital. And over the next 48 hours, PIW moved forward with its involuntary detainment of Rachel, citing a “severe disturbance of affect, behavior, thought process, or judgment that cannot be managed safely in a less restrictive environment,” according to her medical records. Yet while insisting that Rachel’s mental state was so dangerous that she had to be locked in a psych ward against her will, PIW, according to Rachel’s lawsuit, didn’t offer her any individualized therapy or treatment during the entirety of her stay. Instead, she simply loafed around the ward, trying to stay out of trouble.

“I just kept thinking, ‘Well, if I’m actually in crisis, then what is the care that [PIW is] providing?’ ” Rachel says. “There is nothing here.”

According to former employees and the class-action lawsuit, the treatment provided at PIW ranged from lack-luster to nearly nonexistent. Though staff scheduled group-therapy sessions on a near-daily basis, such gatherings offered little benefit to those struggling with addiction or mental illness. “Sometimes [the group-therapy sessions] didn’t occur and they were written down like they did,” one former staffer recalls, “or sometimes they started but nobody paid attention and then it was called off ten minutes in.

“It was a total facade,” the former staffer adds.

In the place of effective therapy, according to former employees and the class-action lawsuit, PIW staff medicated patients to keep them docile and easier to control. Steven Michael Golden Jr., a 28-year-old man who came to PIW in May 2024 after a suicide attempt, said in the class-action lawsuit that the Benadryl he was administered caused him to sleep through much of the day. “It seemed like that was like a base medication that most folks were given,” he tells Washingtonian.

As is the case in many psychiatric hospitals, particularly dangerous patients were injected with powerful antipsychotic drugs designed to subdue aggressive behavior. Because these so-called chemical restraints can deprive patients of agency over their bodies, facilities are supposed to deploy them only as a last resort and when other, less intrusive interventions have been exhausted. But amid the chaos and violence at PIW, according to former employees, some staff came to view the drugs as their only way to keep other patients safe.

“These illegal actions have been and continue to be driven by a focus on profit at the expense of patient care, safety, and treatment.”

“In the beginning, I was like, ‘This is a chemical restraint, we shouldn’t be doing this,’ ” recalls a former PIW nurse. “But then it got to the point where it was so unsafe, [and I] was like, ‘We have to chemically restrain these people because they’re out of control, and I can’t handle the situation if it gets out of control.’ ”

Former staff members say they repeatedly asked PIW leadership to hire security guards to protect them during shifts but were told that because many patients had experienced unpleasant interactions with law enforcement, the presence of guards risked traumatizing them. (In a statement, PIW said that while it has security guards posted in its lobby, using them on patient floors is “considered by many behavioral-health professionals to be counter-productive” in treatment.)

Other actions were harder to justify. When the behavior of one adolescent patient repeatedly got out of hand, according to a former staff member, the teenager was moved to the adult unit—where they would encounter older, more physically imposing patients—as a form of discipline. “They did it as something punitive,” the ex-staffer says, “to punish [them], to intimidate [them].” Dr. Patrick Canavan, the former CEO of St. Elizabeths Hospital, says it is never acceptable to move an adolescent patient to an adult unit as a form of discipline.

According to former staffers and the class-action lawsuit, PIW’s record-keeping could be spotty and flawed. In medical records produced at PIW, according to the class-action lawsuit, Golden was described at one point as a female who’d reported having HIV. “Obviously, I’m not female,” Golden tells Washingtonian. “And I do not have HIV.”

Former PIW patient Gary Wilson’s 2020 stay ended in tragedy. In March 2023, his estate sued the facility and its corporate parent after Wilson died in PIW’s care. According to the lawsuit, Wilson was supposed to be on 24-hour medical supervision because of a rare and life-threatening genetic heart condition. Yet two days after he suffered a near-fatal cardiac episode at the facility, the suit claims, PIW staff left him unattended for more than an hour, during which he stopped breathing. When staff finally did enter his room and found Wilson unresponsive, the suit claims, they failed to call for help or provide any lifesaving treatment for the next 21 minutes. “He was left to die as the [PIW] staff violated the most basic medical standards of care,” the suit states. PIW and UHS have denied these allegations in court documents, and the lawsuit is ongoing.

On the morning after Emancipation Day, Rachel was finally able to request her probable-cause hearing, thanks to a cordless phone borrowed from a neighboring unit and a conversation with her divorce attorney. Later that same day, April 17, 2024, a DC judge vacated the legal basis of her detainment. After spending four days trapped inside the city’s mental-health system, Rachel was going home.

Once PIW had processed her for discharge, Rachel says, she took the elevator down to the exit wearing the same pair of now foul-smelling paper scrubs she’d been issued nearly a week earlier. PIW, however, had misplaced the clothes she’d come in with. So an employee dug through the lost and found and handed her some pants and a T-shirt that were a few sizes too big.

After departing the psychiatric hospital, Rachel walked a few blocks up the street to Target and bought better-fitting clothes. She then headed to the Van Ness–UDC Metro stop, descended the escalator, and stepped onto the subway, as if she were just another commuter on her way home from work.

Over the following days, Rachel struggled to come to terms with what she’d been through. The sight of police cars now filled her with dread. Whenever she visited a doctor, she flashed back to her stay at PIW. “The mistrust is overwhelming,” she says.

Resolving to learn more about PIW and its corporate parent, Rachel contacted DC’s public defender’s services, the local ACLU, and Disability Rights DC. She obtained her medical records, which she says contain glaring errors. For instance, PIW claimed in its discharge summary that it offered Rachel groups on coping skills and anger management, as well as a daily meeting to address the reasons for her hospitalization. None of this, Rachel says, ever took place.

Since February, at least four additional ex-PIW patients, including Steven Michael Golden Jr., have joined Rachel’s lawsuit as plaintiffs. According to former PIW staff members, the lawsuit’s contention that management prioritizes profit over patients rings true—starting with leadership pushing to get as many people into the building as possible. “They are very comfortable with exceeding the maximum capacity for accepting patients and not having a bed for that patient,” a former nurse says. “So that patient might be left in the hallway, might sleep on the floor, might have to sleep on the table in the common area.”

According to former employees, PIW administrators closely monitored the so-called utilization rate of a patient’s medical insurance to ensure it was billing for as many services as insurance would cover. One former nurse tells Washingtonian that a former administrator explained to them that whenever an insurance provider determined a potential patient didn’t actually need the institute’s services—and should therefore not be admitted—PIW administrators contacted the insurance company to lodge appeals. “We do 100 percent appeals even if [the patients] don’t meet medical necessity at the door,” the administrator said, according to the nurse’s written notes on the conversation.

“UHS is money-hungry,” the administrator added.

Some PIW staff, alarmed by what they witnessed each day, began agitating for improvements. Two nurses, for instance, launched what they called “Operation Nightingale” to document poor care and to alert leadership to problems at the facility. But such complaints, they tell Washingtonian, were met with silence or retribution.

One former nurse says that after she raised concerns with leadership, she felt it became harder for her to obtain her desired work schedule. Another ex-nurse says that upon telling the higher-ups about an employee who’d been sleeping on the job, she herself was transferred to a notoriously difficult unit. When the nurse initially resisted the assignment, she says, her manager threatened to report her to the nursing board for patient abandonment. Once the nurse acceded to leadership’s demands and moved to the more dangerous unit, two of her managers came to the ward, questioned her mental fitness, and suggested that perhaps she should be admitted to PIW for a psychiatric evaluation. “It was dystopian,” the nurse says.

The nurse was so frightened, she says, that she reached into her pocket and placed a discreet cellphone call to her parents: “I wanted my parents to be able to hear what was happening, in case anything happened to me.”

PIW told Washingtonian that it does not retaliate against employees and that the former nurse’s claims are “unfounded and without merit.”

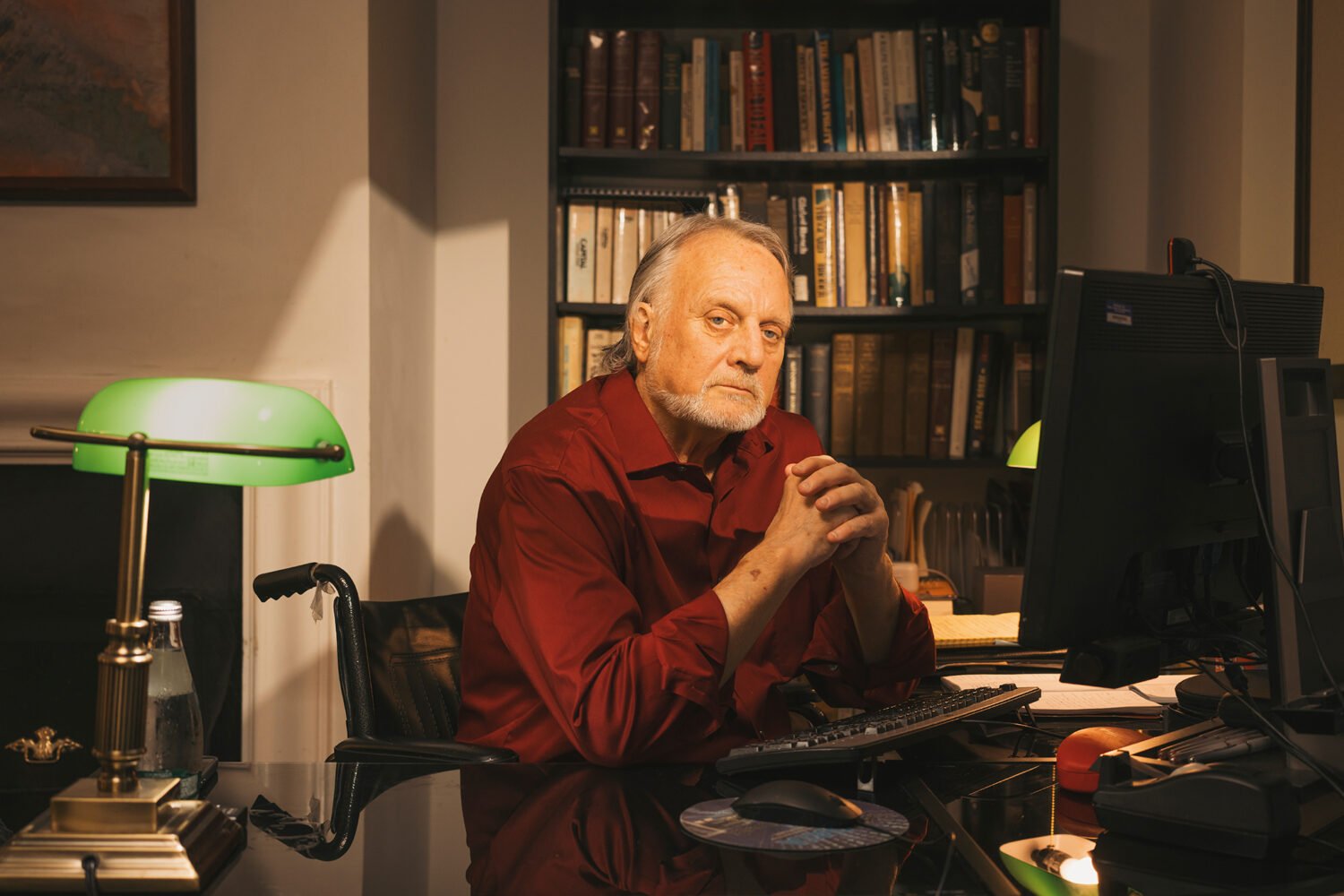

Decrying PIW’s conditions as “unacceptable,” Disability Rights DC’s 2024 report on the facility called on the District government to intervene. But it’s unclear if the city has the willingness—or even the ability—to demand improvements. Hadley Truettner, a former DC public defender who spent three decades advocating for patients involuntarily admitted to PIW, says that well-documented allegations of abuse and neglect go back many years, with political and regulatory leaders repeatedly failing to address them. “The District,” Truettner says, “is really complicit in locking folks up in a facility that they know is dangerous.”

A watchdog report called on the District government to intervene. But it’s unclear if the city is willing–or even able–to demand improvements.

Two different city agencies provide oversight of PIW: DC Health, which licenses community hospitals and oversees care at PIW, and the Department of Behavioral Health, which monitors the care of patients who have been sent involuntarily to PIW. During a daylong DC Council hearing on inpatient psychiatric care held last October that was partially in response to Disability Rights DC’s report, DBH Director Barbara J. Bazron said her agency had recently doubled its monthly visits to PIW. However, DC Health director Ayanna Bennett said the city’s mental-health regulations don’t provide “much specificity around patient safety” at psychiatric institutions like PIW. “It is one of the things that I consider a regulatory hole,” she said.

Meanwhile, DC deputy mayor for health and human services Wayne Turnage questioned whether increasing PIW’s staffing levels would meaningfully increase safety. “It’s a very volatile population,” he said. “They have come from deeply troubled backgrounds. You could see almost one-to-one [staff-to-patient ratios] and you’d still see assaults.”

In a joint statement, DC Health and DBH told Washingtonian that “all allegations of patient abuse or other wrongdoing at any District hospital are investigated” and that “[i]f warranted, appropriate action will be taken to ensure PIW” complies with federal and local regulations. According to former staffers, however, PIW doesn’t always provide the city with complete and accurate information—which means officials may not be fully aware of problems taking place inside. While the facility is required to report so-called Major Unusual Incidents, including physical and sexual assaults, the 2024 Disability Rights DC report found that PIW “has failed to send the requisite MUIs to DBH for years.” During a 16-month period ending March 4, 2024, the report states, PIW submitted just seven MUIs, a seemingly low figure given that the facility “admits and discharges hundreds of patients every month.”

“These low reporting numbers are quite alarming and raise questions as to whether serious incidents at PIW are going unreported,” the report states.

Former staffers told Washingtonian that in the days leading up to scheduled and announced inspections conducted by DC officials, PIW would admit fewer patients, schedule additional staff, and even shuffle patients between wards to make the facility appear safer and more functional than it was. In a statement, PIW denied “any claims that the facility intentionally failed to provide regulators with complete and accurate information.”

At the DC Council hearing, Bazron said DBH had “in the past gotten very little information” from PIW, while PIW chief medical officer Shahbaz Khan said he didn’t have data about the number of incidents and didn’t know if the facility had formally responded to Disability Rights DC’s report. Former PIW nurse Deal, who also spoke at the hearing, urged city authorities to consider modifying UHS’s contract—or scrapping it altogether—in order to improve conditions. “If you want to effect change at PIW,” she said, “you are going to have to affect their bottom line, because that is what UHS cares about.”

Getting tough with PIW or its parent company, however, would force city officials to confront a troubling power imbalance. UHS doesn’t just control PIW; it’s also the owner of George Washington University Hospital in Northwest DC and operates the newly opened Cedar Hill Regional Medical Center in Southeast. And when it comes to acute psychiatric care, UHS has achieved a level of local market dominance that would make John D. Rockefeller blush: During the October hearing, DC Council member Christina Henderson, an at-large Independent, said that nearly six in ten people involuntarily committed to DC’s mental-health system are sent to PIW. (Cedar Hill, St. Elizabeths, and MedStar Washington Hospital Center also receive those kinds of patients.) At a time when a Children’s Hospital official has told the DC Council that local hospitals are seeing increased demand for psychiatric beds—due to a “concerning rise in mental-health crises among our young patients”—the District arguably has become too dependent on a single private facility.

“They’re our only freestanding psychiatric hospital,” Henderson said during the hearing. “I worry on our end that perhaps we are not conducting the oversight necessary because they are our only game in town.”

Truettner is more blunt. “UHS has incredible leverage over the city,” she says. “The city needs them.”

Today, some 16 months after her release from PIW, Rachel still feels the effects of her stay. “I am a person who [was] traditionally extremely high-functioning,” she says, “and that has been very difficult to regain.” Now receiving high-quality mental-health care, she also has found healing in an unexpected place: her research into and lawsuit against PIW and UHS, which has proved empowering. “It is creating a narrative of strength,” she says, “when everything that happened at PIW was to strip that away.”

Through her lawsuit, Rachel is aiming to achieve what Operation Nightingale never could. She wants to hold UHS accountable for trapping her at PIW. By shining a spotlight on the conditions inside, she also hopes to spark real change in the way mental-health care is delivered in the District. “It just felt devastating to see people around me, who actually did need help, getting traumatized by the experience,” she says. “That felt wrong on every level.”

n April 13, 2024, a woman we’ll call Rachel stepped out of her home in Northeast DC following a heated argument with her soon-to-be-ex-husband. A brisk walk through the neighborhood, she thought, would be just the thing to alleviate the stress of her contentious divorce. And sure enough, after walking for about 45 minutes on that spring afternoon, Rachel felt calm, grounded, and ready to return home. But as she turned back onto H Street, just north of Union Station, a team of Metropolitan Police Department officers appeared out of nowhere.

Surrounding Rachel, the officers placed her in handcuffs and—without explanation—secured her in the back of a squad car. “The first thing I thought, she recalls, was ‘Okay, my spouse must have called the police.’ ”

Her hunch was correct. Around the time of their argument, according to a lawsuit she would later join, her husband had reported to police that Rachel, who he claimed had been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, was threatening to kill herself. These allegations, Rachel insists, were untrue. She’d never been diagnosed with any form of mental illness, and while she had made a regrettable comment to her husband in the heat of their argument—“[It] feels like you want me to jump off a bridge”—the remark was certainly not intended to express suicidal ideation.

She was a confused mother of two, simply trying to get home to her young children. Her troubles were just starting.

Nevertheless, on the basis of her husband’s claims, police were now transporting Rachel to the city’s Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program (CPEP) in Southeast DC, where those in mental-health crisis are evaluated and, if necessary, processed into facilities that can provide longer-term care. Upon entering the squat one-story building, next to the DC Jail, Rachel says, she was led into a room with padded walls and a flickering fluorescent light. Eventually, a man with a clipboard arrived, offering neither his name nor his role at the facility.

“What’s going on?” the man said.

As Rachel began to explain the conflict with her husband and the misunderstanding that preceded her detainment, the man put his hand up.

“I’m going to stop you right there,” he said. “It sounds to me like you’re only talking about other people.” The man paused, and Rachel resumed talking. “I think that you need some time to sit with your emotions,” the man said.

Over the next few hours, Rachel says, she insisted to any staff member who would listen that she was not in a state of psychiatric crisis and that she’d never considered harming herself. Yet despite not conducting a proper medical examination, her lawsuit states, officials moved to have her involuntarily detained at CPEP. (Asked about this claim by Washingtonian, city officials did not comment.) The next morning, Rachel was loaded onto a gurney, her arms and legs strapped to the safety rails, and driven in an ambulance to the psychiatric facility where she was to be treated. “I had no idea what was happening, where I was going, and if I was going to be safe,” she says.

Some 45 minutes later, Rachel arrived at the Psychiatric Institute of Washington (PIW), a 152-bed private facility in Northwest DC where the bulk of the city’s involuntary commitments are sent. She entered the hospital as a confused mother of two, simply trying to get home to her young children. Her troubles were just starting.

Opened in 1967, PIW treats adolescents and adults struggling with substance abuse or psychiatric distress. But in recent years, the facility has faced alarming allegations of patient violence, staff misconduct, and systemic dysfunction. The watchdog group Disability Rights DC, the federally designated advocate for people with disabilities in the District, has found in a series of reports that those admitted to PIW are under near-constant threat of patient-on-patient attacks or sexual assault. Recent lawsuits have accused PIW of negligence in the rape of one patient and the death of another. In 2023, a PIW staff member was arrested and charged with sexually abusing a patient in his care. The following year, a group of teenage patients attacked an employee, took their badge, and escaped from the hospital. Last December, a ten-year-old patient who’d been admitted to PIW for depression reported being sexually abused at the facility.

One former health aide tells Washingtonian the violence and disorder inside PIW were so terrifying that she began developing nosebleeds before her shifts. “I mean, this place is actually trauma-inducing,” she says.

This story is based on interviews with a dozen former patients and workers, nearly all of whom requested anonymity to speak candidly. According to some former staffers, the dangerous conditions inside PIW reflect the perceived priorities of its corporate parent, Universal Health Services. The Pennsylvania-based, for-profit conglomerate acquired PIW in 2014. Today, UHS controls more than 300 such facilities around the globe, caring for nearly 4 million patients annually and raking in enough revenue—$15.8 billion in 2024—to make the Fortune 500 list. But the behavioral-health colossus has faced troubling claims of abuse and neglect.

In 2020, UHS reached a $122 million settlement with the Department of Justice to resolve allegations that it had failed to provide adequate training to staff, therapy for patients, and supervision of its employees. Three years later, a South Carolina news station obtained complaints about a UHS-owned youth-treatment facility, “alleging there are bugs, abuse, dangerously low staffing levels, violent fights and blood and vomit smeared throughout the building.” In March 2024, an Illinois jury awarded $535 million in damages to a 13-year-old ex-patient whose mother had sued a nearby UHS-owned facility for negligence after another patient there raped the young girl.

Under UHS’s ownership, according to former staff, PIW routinely sacrifices the well-being of those in its care in order to admit as many patients as possible, bill for whatever services insurance will cover, and deliver financial returns to its shareholders. “It’s almost just like a patient mill,” says one source who spent time in the facility.

“I knew that I was not safe. I was in 100 percent survival mode.”

During her four days trapped inside PIW, Rachel was appalled by what she describes as unsafe conditions and poor quality of care. She later came to believe that her traumatic stay was not the result of honest mistakes or bureaucratic snafus but rather the consequence of a giant corporation perpetually hunting more customers.

In February of this year, Rachel became an unidentified plaintiff in a class-action civil lawsuit against PIW and UHS filed in federal court in DC. Seeking unspecified damages, the lawsuit alleges that the facility and its corporate owner violated the DC Human Rights Act, the Americans With Disabilities Act, and other laws while intentionally inflicting emotional distress. UHS, the suit further claims, “has employed and continues to employ a brazen corporate strategy of involuntarily hospitalizing PIW patients without cause or indication [and] prolonging patients’ hospitalizations unnecessarily and without cause or indication. . . . These illegal actions have been and continue to be driven by a focus on profit at the expense of patient care, safety, and treatment.”

“It’s not a patient-centric culture, despite the fact that they render healthcare services,” plaintiff’s attorney Drew LaFramboise says of UHS. “It’s a shareholder-centric culture.”

K. Nichole Nesbitt, a lawyer for PIW, told Washingtonian in an email that the institution “denies the allegations in the lawsuit and the conclusions of the DC Disability Rights Report and will defend itself vigorously against these claims and matters in court.” The safety and well-being of patients and staff, PIW said in a statement provided by Nesbitt, is its “highest priority,” and the institution “does not discount or disregard any ideas or suggestions” to address safety concerns “for financial reasons.”

PIW declined to comment on many of the additional claims about it contained in this story, citing the privacy restrictions of the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, ongoing litigation, and Washingtonian’s use of anonymous sources. “It is difficult to address the specifics of such claims without being able to understand the full context,” PIW said.

A senior director for corporate public relations at UHS did not provide Washingtonian with a response to emails seeking comment on the class-action lawsuit and the additional claims about UHS contained in this article.

Once the ambulance pulled up to PIW, an employee escorted Rachel up the elevator and into her unit. Inside, Rachel says, she found agitated patients quarreling with staff as shrieks of distress echoed through the halls. Almost immediately, one patient began screaming about the room Rachel had been assigned to, insisting that it actually belonged to him. Meanwhile, a towering, heavyset female patient came within inches of Rachel’s face, only to begin caressing Rachel’s hair and complimenting her on her appearance. Patients used encounters like this, Rachel says, to test how new arrivals would react.

“It was sort of like entering jail, where people are trying to figure out if you can be bullied,” she says.

Rachel was desperate to prove she was not in a psychiatric crisis and could therefore be released and return home to her children. But for now, other priorities were more urgent. “I knew that I was not safe,” she says. “I was in 100 percent survival mode.”

Former staff say the violence at PIW is alarming and routine. During 2023 alone, according to Disability Rights DC, patient-on-patient attacks resulted in broken bones, human bite marks, and emergency-room visits. “It looks like she was attacked by an animal,” a PIW staff member said of the victim of one such assault, in a 2024 incident report obtained by the watchdog group.

Employees are targets as well. Former employees tell Washingtonian that one staff member had a door repeatedly closed on his head by a patient, and another had urine thrown at her. When things got really bad, one former PIW employee told Disability Rights DC, units descended into rioting.

The environment was so explosive, former patients say, because PIW failed to deliver the resources necessary to properly care for its already challenging patient population. On any given day, according to former employees, the facility contained a volatile blend of locals in mental-health crisis, addicts coming down off drugs, and people experiencing homelessness. “You’re mixing, like, DC gangsters with flamboyant guys who are in there because they’ve done too much meth,” a former staffer says.

Conditions in the facility aggravated patients and amplified tensions. According to the class-action lawsuit and what former staff told Washingtonian, the units often stank of urine and feces. According to interviews with former staffers and a 2024 employee complaint obtained by Disability Rights DC, the temperatures inside the building got so cold that ice sometimes formed on the windows. And according to the class-action lawsuit, staff members told patients that the toilet had to be flushed three times to get hot water in the showers. Lack of structured activities and outdoor recreation meant patients passed most of their time milling aimlessly around the units, stewing in boredom and restlessness. Frequent shortages of basic necessities turned latent discontent into outright conflict. According to what former staff told Washingtonian and an employee complaint obtained by Disability Rights DC, PIW regularly failed to provide enough food to its patients—a deficiency all the more distressing because the medications prescribed to many patients often increased their appetites. Nurses and aides regularly went out of pocket to purchase snacks for hungry patients, but they couldn’t keep everyone sated. “Food was one of the biggest things that patients would fight about,” says one former nurse, “because we wouldn’t have enough of one kind or another.” (PIW denied failing to provide enough food for its patients.)

PIW’s staff was unable to prevent the escalation of violence. This was partially due to what former staffers describe as a chronic worker shortage, which often forced solitary employees to manage unreasonably large groups of patients. A city-government review of the facility’s staffing levels over a 15-day period in May 2022 found that many—and sometimes all—of its units were without requisite staff on all 15 of those days. Last year, former PIW nurse Elizabeth Deal testified before the DC Council that staffing levels at the facility—one nurse and one or two technicians for 18 to 21 patients—were insufficient. “I once worked a unit by myself with 19 patients,” another former mental-health aide told Washingtonian.

Former staffers say the quality of individual workers was also a factor. Many employees chose to work at PIW out of a genuine desire to help patients in distress—but others, according to ex-staff, were drawn by the competitive pay and lacked the passion that this difficult field demands. One former employee recalls finding a night nurse fast asleep while on duty: “She was wearing a neck pillow, propped her feet up, had blinders on and everything.” Other staff members were so uncommitted to PIW’s mission, a former employee says, that they questioned why drug addicts or the mentally ill would be treated at all.

“Literally, some of them are like, ‘Oh, [that patient] just needs to pray or find Jesus,’ ” the former employee recalls.

In November 2023, former patient Leon Allen sued PIW, alleging he’d suffered rib and hip fractures when he was body-slammed by a staff member during a dispute over telephone access. The case was later dismissed. In December 2023, DC police arrested a 44-year-old PIW staff member, Jerry Mack, and charged him with first-degree sexual abuse of an adolescent patient in his care. Mack subsequently pleaded guilty to one count of first-degree sexual abuse of a ward and was sentenced to three years in prison.

Last December, a different former female patient, Ambriel Rose Veldkamp, sued PIW for negligence, claiming that it failed to prevent her from being raped by a man at the facility in 2021. In her lawsuit, Veldkamp said two other men may have watched or participated in the assault as well, though she can’t say for sure because the medication prescribed to her may have caused her to black out. PIW has denied responsibility for the incident in court documents, and the lawsuit is ongoing.

In December 2024, according to an investigative survey conducted by the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, a ten-year-old patient who’d been admitted to PIW for depression reported being sexually abused by a 15-year-old patient. According to the report, the ten-year-old told PIW staff that the older patient “came into my room and touched my [genitalia] and my private area.” In its investigation, CMS found that PIW had violated federal regulations designed to prevent sexual-abuse incidents like this in two ways: first, by permitting patients under age 18 and with an age difference of more than three years to room together; second, by failing to keep bedroom doors locked when not in use. In addition, according to the report, PIW staff did not alert DC’s Child and Family Services Agency to the incident, even though they’re required by law to do so.

PIW declined to comment on Mack’s arrest, Allen’s lawsuit, or Veldkamp’s lawsuit, and did not provide comment on the sexual-abuse investigation involving the ten-year-old patient. UHS did not provide comment.

During her first few hours at PIW, Rachel says, she learned to avoid conflict by disappearing into a corner or reading alone on her bed. Although physically safe, she remained disoriented and confused. She had no idea what rights she possessed, how long she would be stuck there, or what she could do to prove this was all a mistake. Most of the staff, she felt, had no interest in helping. “It was just a wall of silence and random people who didn’t introduce themselves,” she recalls.

Around 11:30 am on her first day, however, she met with a psychiatrist, Dr. Menachem Groden. Unlike other staff, Rachel says, he was patient and engaged, listening carefully as she explained her acrimonious divorce and the misunderstanding with her husband. In his notes of their conversation, portions of which are contained in the class-action lawsuit, Dr. Groden described Rachel as “calm and cooperative” with a “linear and logical” thought process and “good” judgment. As their discussion drew to a close, Rachel tells Washingtonian, the psychiatrist made a remark: “I’m so sorry this is happening. You shouldn’t be here.”

Dr. Groden didn’t have discharge privileges—and because it was a Sunday, he wouldn’t have been able to release her even if he did. Instead, Rachel says, he instructed her to find PIW’s court liaison the following morning and request a probable-cause hearing to challenge the basis of her detainment.

She had no idea what rights she possessed, how long she would be stuck there, or what she could do to prove this was all a mistake.

At 9 am sharp the next day, Rachel says, she planted herself in a chair by a staff desk, eager to meet the court liaison. Hours went by. Rachel says she asked a staff member for assistance, but the employee didn’t know who the court liaison was. The phones in the unit were broken. A nurse dialed PIW’s patient advocate on her mobile phone and handed it to Rachel. The patient advocate, however, was on vacation.

At around 4 pm, after roughly seven hours of waiting, Rachel says she flagged down a female staff member and explained she was looking for the court liaison.

“Oh,” the woman replied, “I’m the court liaison.”

“I’m trying to [request] a probable-cause hearing,” Rachel explained.

The liaison broke the bad news. “The courts are closed now,” she said, “and tomorrow is a court holiday [for Emancipation Day].”

The treatment provided, according to former employees and a lawsuit, ranged from lackluster to nearly nonexistent.

In spite of Dr. Groden’s findings, Rachel remained trapped in the mental hospital. And over the next 48 hours, PIW moved forward with its involuntary detainment of Rachel, citing a “severe disturbance of affect, behavior, thought process, or judgment that cannot be managed safely in a less restrictive environment,” according to her medical records. Yet while insisting that Rachel’s mental state was so dangerous that she had to be locked in a psych ward against her will, PIW, according to Rachel’s lawsuit, didn’t offer her any individualized therapy or treatment during the entirety of her stay. Instead, she simply loafed around the ward, trying to stay out of trouble.

“I just kept thinking, ‘Well, if I’m actually in crisis, then what is the care that [PIW is] providing?’ ” Rachel says. “There is nothing here.”

According to former employees and the class-action lawsuit, the treatment provided at PIW ranged from lack-luster to nearly nonexistent. Though staff scheduled group-therapy sessions on a near-daily basis, such gatherings offered little benefit to those struggling with addiction or mental illness. “Sometimes [the group-therapy sessions] didn’t occur and they were written down like they did,” one former staffer recalls, “or sometimes they started but nobody paid attention and then it was called off ten minutes in.

“It was a total facade,” the former staffer adds.

In the place of effective therapy, according to former employees and the class-action lawsuit, PIW staff medicated patients to keep them docile and easier to control. Steven Michael Golden Jr., a 28-year-old man who came to PIW in May 2024 after a suicide attempt, said in the class-action lawsuit that the Benadryl he was administered caused him to sleep through much of the day. “It seemed like that was like a base medication that most folks were given,” he tells Washingtonian.

As is the case in many psychiatric hospitals, particularly dangerous patients were injected with powerful antipsychotic drugs designed to subdue aggressive behavior. Because these so-called chemical restraints can deprive patients of agency over their bodies, facilities are supposed to deploy them only as a last resort and when other, less intrusive interventions have been exhausted. But amid the chaos and violence at PIW, according to former employees, some staff came to view the drugs as their only way to keep other patients safe.

“These illegal actions have been and continue to be driven by a focus on profit at the expense of patient care, safety, and treatment.”

“In the beginning, I was like, ‘This is a chemical restraint, we shouldn’t be doing this,’ ” recalls a former PIW nurse. “But then it got to the point where it was so unsafe, [and I] was like, ‘We have to chemically restrain these people because they’re out of control, and I can’t handle the situation if it gets out of control.’ ”

Former staff members say they repeatedly asked PIW leadership to hire security guards to protect them during shifts but were told that because many patients had experienced unpleasant interactions with law enforcement, the presence of guards risked traumatizing them. (In a statement, PIW said that while it has security guards posted in its lobby, using them on patient floors is “considered by many behavioral-health professionals to be counter-productive” in treatment.)

Other actions were harder to justify. When the behavior of one adolescent patient repeatedly got out of hand, according to a former staff member, the teenager was moved to the adult unit—where they would encounter older, more physically imposing patients—as a form of discipline. “They did it as something punitive,” the ex-staffer says, “to punish [them], to intimidate [them].” Dr. Patrick Canavan, the former CEO of St. Elizabeths Hospital, says it is never acceptable to move an adolescent patient to an adult unit as a form of discipline.

According to former staffers and the class-action lawsuit, PIW’s record-keeping could be spotty and flawed. In medical records produced at PIW, according to the class-action lawsuit, Golden was described at one point as a female who’d reported having HIV. “Obviously, I’m not female,” Golden tells Washingtonian. “And I do not have HIV.”

Former PIW patient Gary Wilson’s 2020 stay ended in tragedy. In March 2023, his estate sued the facility and its corporate parent after Wilson died in PIW’s care. According to the lawsuit, Wilson was supposed to be on 24-hour medical supervision because of a rare and life-threatening genetic heart condition. Yet two days after he suffered a near-fatal cardiac episode at the facility, the suit claims, PIW staff left him unattended for more than an hour, during which he stopped breathing. When staff finally did enter his room and found Wilson unresponsive, the suit claims, they failed to call for help or provide any lifesaving treatment for the next 21 minutes. “He was left to die as the [PIW] staff violated the most basic medical standards of care,” the suit states. PIW and UHS have denied these allegations in court documents, and the lawsuit is ongoing.

On the morning after Emancipation Day, Rachel was finally able to request her probable-cause hearing, thanks to a cordless phone borrowed from a neighboring unit and a conversation with her divorce attorney. Later that same day, April 17, 2024, a DC judge vacated the legal basis of her detainment. After spending four days trapped inside the city’s mental-health system, Rachel was going home.

Once PIW had processed her for discharge, Rachel says, she took the elevator down to the exit wearing the same pair of now foul-smelling paper scrubs she’d been issued nearly a week earlier. PIW, however, had misplaced the clothes she’d come in with. So an employee dug through the lost and found and handed her some pants and a T-shirt that were a few sizes too big.

After departing the psychiatric hospital, Rachel walked a few blocks up the street to Target and bought better-fitting clothes. She then headed to the Van Ness–UDC Metro stop, descended the escalator, and stepped onto the subway, as if she were just another commuter on her way home from work.

Over the following days, Rachel struggled to come to terms with what she’d been through. The sight of police cars now filled her with dread. Whenever she visited a doctor, she flashed back to her stay at PIW. “The mistrust is overwhelming,” she says.

Resolving to learn more about PIW and its corporate parent, Rachel contacted DC’s public defender’s services, the local ACLU, and Disability Rights DC. She obtained her medical records, which she says contain glaring errors. For instance, PIW claimed in its discharge summary that it offered Rachel groups on coping skills and anger management, as well as a daily meeting to address the reasons for her hospitalization. None of this, Rachel says, ever took place.

Since February, at least four additional ex-PIW patients, including Steven Michael Golden Jr., have joined Rachel’s lawsuit as plaintiffs. According to former PIW staff members, the lawsuit’s contention that management prioritizes profit over patients rings true—starting with leadership pushing to get as many people into the building as possible. “They are very comfortable with exceeding the maximum capacity for accepting patients and not having a bed for that patient,” a former nurse says. “So that patient might be left in the hallway, might sleep on the floor, might have to sleep on the table in the common area.”

According to former employees, PIW administrators closely monitored the so-called utilization rate of a patient’s medical insurance to ensure it was billing for as many services as insurance would cover. One former nurse tells Washingtonian that a former administrator explained to them that whenever an insurance provider determined a potential patient didn’t actually need the institute’s services—and should therefore not be admitted—PIW administrators contacted the insurance company to lodge appeals. “We do 100 percent appeals even if [the patients] don’t meet medical necessity at the door,” the administrator said, according to the nurse’s written notes on the conversation.

“UHS is money-hungry,” the administrator added.

Some PIW staff, alarmed by what they witnessed each day, began agitating for improvements. Two nurses, for instance, launched what they called “Operation Nightingale” to document poor care and to alert leadership to problems at the facility. But such complaints, they tell Washingtonian, were met with silence or retribution.

One former nurse says that after she raised concerns with leadership, she felt it became harder for her to obtain her desired work schedule. Another ex-nurse says that upon telling the higher-ups about an employee who’d been sleeping on the job, she herself was transferred to a notoriously difficult unit. When the nurse initially resisted the assignment, she says, her manager threatened to report her to the nursing board for patient abandonment. Once the nurse acceded to leadership’s demands and moved to the more dangerous unit, two of her managers came to the ward, questioned her mental fitness, and suggested that perhaps she should be admitted to PIW for a psychiatric evaluation. “It was dystopian,” the nurse says.

The nurse was so frightened, she says, that she reached into her pocket and placed a discreet cellphone call to her parents: “I wanted my parents to be able to hear what was happening, in case anything happened to me.”

PIW told Washingtonian that it does not retaliate against employees and that the former nurse’s claims are “unfounded and without merit.”

Decrying PIW’s conditions as “unacceptable,” Disability Rights DC’s 2024 report on the facility called on the District government to intervene. But it’s unclear if the city has the willingness—or even the ability—to demand improvements. Hadley Truettner, a former DC public defender who spent three decades advocating for patients involuntarily admitted to PIW, says that well-documented allegations of abuse and neglect go back many years, with political and regulatory leaders repeatedly failing to address them. “The District,” Truettner says, “is really complicit in locking folks up in a facility that they know is dangerous.”

A watchdog report called on the District government to intervene. But it’s unclear if the city is willing–or even able–to demand improvements.

Two different city agencies provide oversight of PIW: DC Health, which licenses community hospitals and oversees care at PIW, and the Department of Behavioral Health, which monitors the care of patients who have been sent involuntarily to PIW. During a daylong DC Council hearing on inpatient psychiatric care held last October that was partially in response to Disability Rights DC’s report, DBH Director Barbara J. Bazron said her agency had recently doubled its monthly visits to PIW. However, DC Health director Ayanna Bennett said the city’s mental-health regulations don’t provide “much specificity around patient safety” at psychiatric institutions like PIW. “It is one of the things that I consider a regulatory hole,” she said.

Meanwhile, DC deputy mayor for health and human services Wayne Turnage questioned whether increasing PIW’s staffing levels would meaningfully increase safety. “It’s a very volatile population,” he said. “They have come from deeply troubled backgrounds. You could see almost one-to-one [staff-to-patient ratios] and you’d still see assaults.”

In a joint statement, DC Health and DBH told Washingtonian that “all allegations of patient abuse or other wrongdoing at any District hospital are investigated” and that “[i]f warranted, appropriate action will be taken to ensure PIW” complies with federal and local regulations. According to former staffers, however, PIW doesn’t always provide the city with complete and accurate information—which means officials may not be fully aware of problems taking place inside. While the facility is required to report so-called Major Unusual Incidents, including physical and sexual assaults, the 2024 Disability Rights DC report found that PIW “has failed to send the requisite MUIs to DBH for years.” During a 16-month period ending March 4, 2024, the report states, PIW submitted just seven MUIs, a seemingly low figure given that the facility “admits and discharges hundreds of patients every month.”

“These low reporting numbers are quite alarming and raise questions as to whether serious incidents at PIW are going unreported,” the report states.

Former staffers told Washingtonian that in the days leading up to scheduled and announced inspections conducted by DC officials, PIW would admit fewer patients, schedule additional staff, and even shuffle patients between wards to make the facility appear safer and more functional than it was. In a statement, PIW denied “any claims that the facility intentionally failed to provide regulators with complete and accurate information.”

At the DC Council hearing, Bazron said DBH had “in the past gotten very little information” from PIW, while PIW chief medical officer Shahbaz Khan said he didn’t have data about the number of incidents and didn’t know if the facility had formally responded to Disability Rights DC’s report. Former PIW nurse Deal, who also spoke at the hearing, urged city authorities to consider modifying UHS’s contract—or scrapping it altogether—in order to improve conditions. “If you want to effect change at PIW,” she said, “you are going to have to affect their bottom line, because that is what UHS cares about.”

Getting tough with PIW or its parent company, however, would force city officials to confront a troubling power imbalance. UHS doesn’t just control PIW; it’s also the owner of George Washington University Hospital in Northwest DC and operates the newly opened Cedar Hill Regional Medical Center in Southeast. And when it comes to acute psychiatric care, UHS has achieved a level of local market dominance that would make John D. Rockefeller blush: During the October hearing, DC Council member Christina Henderson, an at-large Independent, said that nearly six in ten people involuntarily committed to DC’s mental-health system are sent to PIW. (Cedar Hill, St. Elizabeths, and MedStar Washington Hospital Center also receive those kinds of patients.) At a time when a Children’s Hospital official has told the DC Council that local hospitals are seeing increased demand for psychiatric beds—due to a “concerning rise in mental-health crises among our young patients”—the District arguably has become too dependent on a single private facility.

“They’re our only freestanding psychiatric hospital,” Henderson said during the hearing. “I worry on our end that perhaps we are not conducting the oversight necessary because they are our only game in town.”

Truettner is more blunt. “UHS has incredible leverage over the city,” she says. “The city needs them.”

Today, some 16 months after her release from PIW, Rachel still feels the effects of her stay. “I am a person who [was] traditionally extremely high-functioning,” she says, “and that has been very difficult to regain.” Now receiving high-quality mental-health care, she also has found healing in an unexpected place: her research into and lawsuit against PIW and UHS, which has proved empowering. “It is creating a narrative of strength,” she says, “when everything that happened at PIW was to strip that away.”

Through her lawsuit, Rachel is aiming to achieve what Operation Nightingale never could. She wants to hold UHS accountable for trapping her at PIW. By shining a spotlight on the conditions inside, she also hopes to spark real change in the way mental-health care is delivered in the District. “It just felt devastating to see people around me, who actually did need help, getting traumatized by the experience,” she says. “That felt wrong on every level.”

This article appears in the September 2025 issue of Washingtonian.