Federal workers have had a challenging year, to say the least. Given President Trump’s efforts to gut and restructure the bureaucracy, soundtracked by the roar of Elon Musk’s DOGE chainsaw in the administration’s early months, many civil servants have either lost their jobs or accepted deferred-resignation packages. For those who remain, this ongoing government shutdown is a particularly pointed blow, as the White House threatens even more mass layoffs.

Christoph Herpfer is an assistant professor of business administration at the University of Virginia. His research finds that shutdowns continue to snarl government efficiency long after they end—mainly because of their impact on the morale of federal employees. We asked him more about these long-term shutdown consequences and how he expects they’ll manifest at a time when many civil servants are already feeling devalued in the workplace.

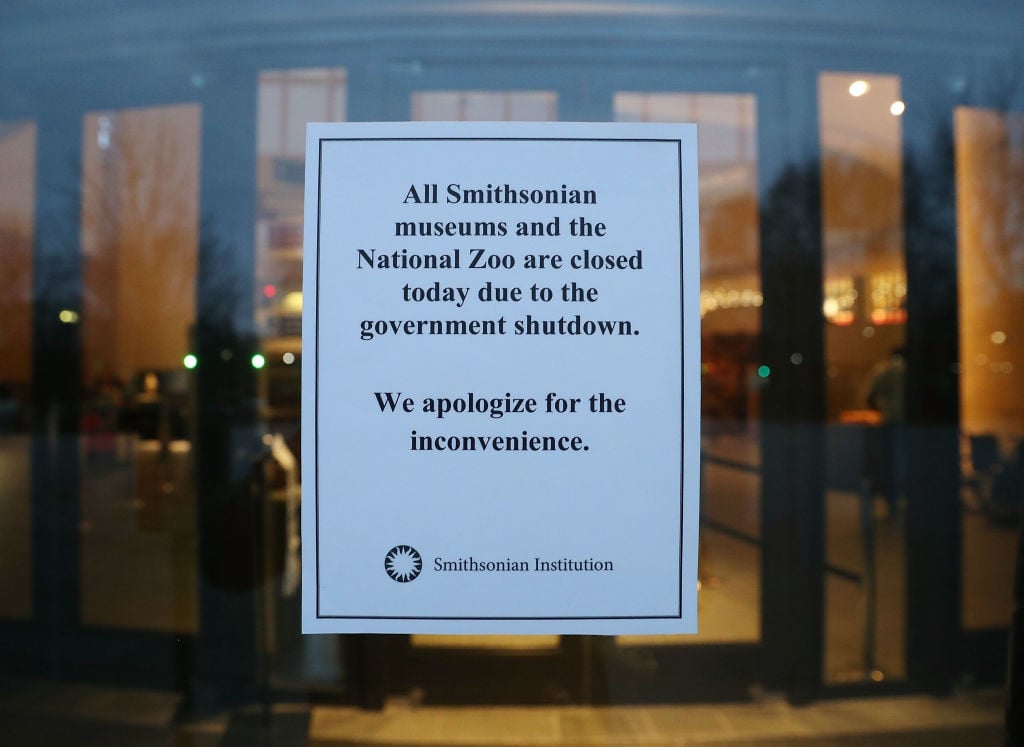

Here in DC, we’re all pretty familiar with the immediate effects of a shutdown—suspended government services and financial insecurity for furloughed federal workers. What less obvious impacts have you encountered in your research?

The obvious impacts are immediate and publicized. You have a bunch of yellow tape in front of some national parks, government agencies shutting down, disgruntled government employees who are not getting paid and run into personal finance issues. And then when the dust settles, it seems like it’s all over. The employees are receiving back pay, so they get paid for all the money that they missed out on. What we find is that the real costs actually start only after these employees are back at their desks. They lose morale and motivation, and once they’re back at their desks, they will spend quite a bit of time on LinkedIn looking for a new job. And they’re not in a rush. But within roughly four to eight quarters—within two years—roughly 10,000 to 15,000 employees after a major shutdown leave government employment for good.

If it can take as long as two years, how do we know that they’re leaving because of the shutdown?

There’s two answers to this. One is a bit technical: We obtained almost complete personal records from the Office of Personnel Management via Freedom of Information Act requests, which give us—for every employee in the government for every quarter—their employment status, their salary, their socioeconomic data, as well as information on whether they left employment or whether they stayed on. And we compare employees in agencies where everybody got sent home to the equivalent employees in agencies where they kept on working. And so, to the degree that the statistical methods make sure that these two groups are similar, the only difference between them is that some of them got furloughed and others did not.

But there’s an even more direct answer. We can just ask the employees themselves. And the federal government has done this. They’ve only done this once, in 2020, after the big shutdown seven years ago. They asked employees whether they are looking for a new job, and conditionally on looking for a new job, they asked them whether the shutdown has something to do with it. And when we compare the answers of employees who got furloughed with the answers of employees who didn’t get furloughed, we find super strong evidence—something like 75% of the employees looking for a new job, that were working in agencies where almost everybody got furloughed, say they’re looking for a job specifically because the furlough destroyed their morale. This gives us a pretty good idea that it is a causal link between being furloughed and looking for a new job.

So if you’re working at an agency where you’re still able to do your job during a shutdown, even though you’re not going to be paid on time, your morale is less likely to take a hit.

Isn’t that interesting? Some excepted employees that keep on working are still being paid, but many of them actually go back to work without getting paid. The cynical view would be to say, if you’re an excepted employee, you have to work without pay, and if you are being furloughed, you get a free vacation. It seems that this is really destroying the morale of these employees. They feel like they’re being not valued. That was a very interesting insight from this. It’s really the furlough that seems to demoralize these employees.

Your research finds that many federal workers immediately set out to find non-government jobs once they return to their offices after a furlough. How do you expect these findings to translate to this current Trump era, in which we’ve already seen so many feds lose their jobs and struggle to land in the private sector?

There’s two things that make the current shutdown unique. The first is that the federal government already lost something in the region of 200,000 to 300,000 employees this year, following the attempts by the current administration to increase efficiency and slim down the government. So the whole DOGE affair already made a lot of people leave the government workforce. Now, this could mean that the current shutdown is being amplified—or it could be dampened. It could be amplified in the sense that, for many employees, this might be the straw that breaks the camel’s back. They kind of muddled through this year. They survived the initial cuts, and now this is the final straw for them. But it could also be that this is dampening the effect, in the sense that the employees who were already thinking about leaving, were reasonably close to retirement, or with the highest likelihood of finding a job in the private sector already left. They took the buyout and they are already gone, which means that the people who are left are the people who either have little outside opportunities or are diehard civil servants who will just stick to it no matter what. Personally, I know a bunch of spectacular former federal employees who left the government and took the buyout. My sense is a lot of very good people might have already left. So this shutdown might be having less of an effect than previous ones, but we will only know this once the actual data comes out.

You also find that federal employees’ performance suffers after a shutdown, in line with that diminished morale. It’s safe to say that feds are already pretty demoralized right now. I’m sure the shutdown won’t help, but we’ve already been living in this low-morale environment for several months now.

We attribute this disruption in the quality of performance to the loss of human capital. What we can show in our work is that, after the shutdown, we have about 13,000 people leaving, and these people don’t get replaced. So the loss in human capital seems almost permanent, or at least long-running. What we find is that the agencies that are particularly affected by the shutdown—and then lose more employees—see a deterioration in their performance metrics. For example, the fraction of incorrect, faulty government payments goes up by 1 percentage point. And while that doesn’t sound like a big number, 1 percentage point becomes pretty big once we’re talking about a government that is spending hundreds of billions of dollars. We estimate that this drop in payment accuracy costs taxpayers about $500 million every single year after the shutdown, and these costs are dwarfing all the direct costs of shutdown that everybody’s focusing on right now.

Has anything come up in your research that suggests potential solutions for how agencies can promote morale and performance among furloughed workers when they do return to the office?

There is some of that in our work indirectly. Our model allows us to say that the shock to morale is massive and corresponds to a roughly 10% drop in payment. That implies that what the government could do to increase morale would be to increase salaries, but I highly doubt there’s a 10% salary increase on the horizon to make up for the loss in morale. There’s one country in the world that actually takes this very seriously, and that is Singapore. The Singaporeans say, “If we want to compete for the best human capital out there, we cannot rely on people’s intrinsic motivation to serve the government. We need to pay up.” So Singapore famously pays its civil servants wages that are oriented on the market, wages that they could get if they were doing the same job in the private sector. They run the government much closer to an actual company, and I find that a very interesting thought experiment.

Another thing: Your readers in the DC area will be familiar with the term “shadow government”—all these contractors and consulting firms that are providing services to the government. And in recent decades, we’ve seen that more and more functions that used to be performed by the government itself have been outsourced to these providers. And you find that, after the shutdown, these agencies that lose all this human capital rely more heavily on these external contractors—to the point where, for every dollar they save on payroll because somebody left, they spend two-and-a-half dollars on contractors. They end up paying two-and-a-half times as much for the outsourcing than what they used to pay for the internal employees.

So this basically leaves only a single avenue to avoid this whole thing, and that is the idea that maybe we can avoid this mechanism of shutdowns altogether. There are sister bills that are being introduced by Republicans and Democrats who say that this is not the optimal way to handle budget negotiations, and they have proposed to continue government funding at last year’s level when we reach an impasse about next year’s budget. I think this is a beautiful effort, and it very much reflects our work that this is a bipartisan issue. It doesn’t matter what your view is of the federal government, if you think it’s effective or not. The truth of the matter is that you want the people who handle all this money to be competent, hardworking, and motivated. No matter on which side of the political aisle you are, our results indicate very strongly that shutdowns are something that you don’t want.