Once the highest paid lobbyist in Washington, Jack Abramoff can’t escape the constant reminders of his remarkable fall.

He complains that the word “disgraced” nearly always precedes his name when he’s mentioned by the media. His black Lexus SUV, once a gleaming status symbol, looks dated now, its leather seats cracked. A Rolex hangs on his wrist like an artifact from another time. When I first spotted it, I wondered what kind of dent it could put in the $44 million he owes in restitution.

He still refers to Grover Norquist as his “old buddy,” but the men haven’t spoken in a decade, and Norquist—the powerful president of Americans for Tax Reform—never returned my calls and e-mails asking if he’d like to chat about his friend Jack.

When I met Abramoff at a coffee shop near Dupont Circle last November, I was surprised to feel a twinge of pity for the former Republican superlobbyist, poster boy of Beltway corruption. Three years out of federal prison, in his navy-blue golf jacket and baggy slacks, he looked like any other chubby, suburban dad.

But then we got to talking.

The most important thing about Abramoff hasn’t changed: his unparalleled talent for winning people over. “He could sell sand to the Saudis,” say several of his former lobbying colleagues. “Jack could talk a dog off a meat truck,” says Neil Volz, who got two years of probation for his involvement with Abramoff.

Others are harsher. “He’s a modern-day Elmer Gantry,” says Tom Rodgers, the whistleblower who helped bring Abramoff down, referring to the fictional con man.

Somehow, Abramoff can make boasts sound self-deprecating. He can cast himself as a hero while making you believe you arrived at that conclusion on your own. For most of his life, this was his gift. But now it’s Abramoff’s curse.

It’s the reason—as he embarks on his second act in Washington, claiming to be a changed man dedicated to reforming the government—that there’s one question on everyone’s mind: Is this just another of Abramoff’s scams?

• • •

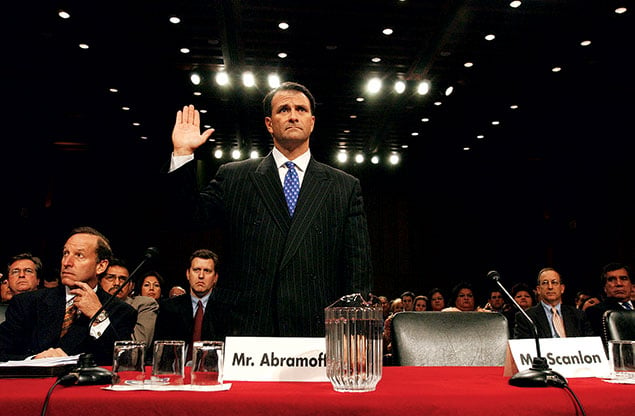

Far from skulking away quietly—as most people would if they’d been dressed down by a Senate committee for swindling their American Indian clients and buying favors from lawmakers; had their racist e-mails exposed to the world; and served time for conspiracy, fraud, and tax evasion—Abramoff, 54, has again placed himself in the public eye.

He started by writing Capitol Punishment—half memoir, half critique of what he calls “the favor factory” in Congress—and launching his book tour with an interview on 60 Minutes with Lesley Stahl.

Until it was canceled in July, he hosted his own radio show, Jack Abramoff, live on Sirius XM channel 168 every Sunday. He says he’s trying to find a way to get it back on the air. But mostly, Abramoff is focused on rebranding himself as a reformer.

For fees as high as $20,000, much of which he must turn over to the government, he gives speeches across the country about corruption on Capitol Hill. He’s working with United Republic, a group dedicated to taking money out of politics, on a grassroots campaign to enact far-reaching ethics legislation to restrict interaction between lobbyists and elected officials.

“This is very much like the FBI or the NSA hiring world-class hackers when they finish their jail terms to try to hack into their agencies’ systems,” says Josh Silver, United Republic’s CEO. “Jack said, ‘These are the laws needed to stop me.’ ”

He also has three TV-show concepts in the works as well as an idea for a series of six novels he wants to write and then turn into movies. He says they’ll be on the scale of the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

The declaration calls to mind the motto Abramoff lived by during his lobbying days: “If it’s worth doing, it’s worth overdoing.”

• • •

It’s a cold, drizzly night in Stamford, Connecticut, and Abramoff is in his element. He’s here to speak—for a $7,500 fee—at a meeting of the Prometheum, a men’s club that bills itself as “a fraternal organization, inspired by the founders of the United States,” with a mission to foster debate and the free exchange of ideas. The invitation to the evening’s event described the dress code as “black tie (not optional).”

The club’s president, Steve Bowling, has known Abramoff since they were undergraduates at Brandeis University. Like most of Abramoff’s remaining friends, Bowling has nothing to do with the Washington power structure. He’s trying to start a tilapia farm.

Abramoff and I find our places at a table for eight in a dimly lit banquet room. An elderly man, David Parent, sits to Abramoff’s right. It turns out he was one of Abramoff’s pen pals while Abramoff was in prison. Parent says he was inspired to write to him because the Bible encourages people to reach out to those who aren’t easy to like. Because Parent lives nearby, Abramoff invited him to the speech so they could meet in person for the first time.

About 40 Prometheum members attend. Many arrive leery of Abramoff. Paul Nakian, a lawyer and self-proclaimed “hard-left-leaning liberal,” tells me that when he learned Abramoff would be the evening’s speaker, he was certain he would be “a slimeball.”

Before long, though, Abramoff holds court. He regales our table with tales of meeting Lesley Stahl and Piers Morgan. He talks about his efforts to improve his vocabulary while in jail—he made flash cards with the goal of learning 80 new words a week. When Parent begins to interrupt, Abramoff puts a hand on the man’s arm and softly tells him he’s not done talking.

Finally, it’s time for Abramoff’s speech. He delivers story after story with the rhythm of a standup comic; there’s a lot of buildup and punch lines that usually make the audience laugh. There are somber parts, too, such as when he introduces Parent, telling the crowd how the then-stranger gave him “a spark of hope at mail call.”

Abramoff talks about the day he pleaded guilty and how grateful he was to have at least been investigated by honest prosecutors and FBI agents. He describes looking down during his plea and seeing that the prosecutors “were teary.” He says he told them afterward, “When you go [to heaven], you’ll be just fine because you’ll bring with you, as exhibit A, the tears you shed in this room.”

He closes by talking about the work he’s doing with government-reform groups to get ethics legislation passed: “For me, it’s part recompense. It’s part wanting to do the right thing. It’s not easy getting up and telling my story.”

If that’s true, he sure makes it look easy. The men give him a standing ovation. He then navigates through a sea of outstretched hands and winds his way to the back of the room, where he takes a seat at a table next to a stack of his books. A line of new converts stretches before him.

As I head to the parking lot, I run into Paul Nakian, the liberal lawyer who predicted Abramoff would be a slimeball. Is he ducking out, one of the few who don’t want an autograph?

No, he tells me. He’s hurrying to his car to get his wallet so he can buy an autographed copy of Capitol Punishment.

• • •

Nick Penniman had a similar conversion. He first met Abramoff in December 2011. Penniman, then working for United Republic, had spent the better part of two years researching the Abramoff scandal.

So when he awoke that winter morning, he could hardly believe what he was about to do. He felt reluctant, questioning whether he should have agreed to do Harvard professor Lawrence Lessig this particular favor.

Lessig, a scholar of ethics, had invited Abramoff to Cambridge to talk about his book. Then he had called Penniman, who lives in Boston, to tell him he ought to sit down with Abramoff while the ex-lobbyist was in town.

Though uneasy, Penniman forced himself out the door. When he entered the restaurant of the Charles Hotel off Harvard Square, there was Abramoff. The great villain wore an oxford shirt with an iPhone in the pocket.

Penniman decided he would gradually wade into the business of campaign-finance reform and first ask Abramoff about his time in prison. To Penniman’s surprise, his nerves calmed almost immediately.

He was disarmed by how forthcoming Abramoff was. “I learned more about him as a person and about the time he spent in jail, about what that did to his family,” he says. “I was able to see beyond the caricature of Jack Abramoff into a man who went from the height of power to a completely broken father behind bars.”

Despite warnings from others—including one who suspected Abramoff was a mole crafting some kind of exposé, à la James O’Keefe’s undercover ACORN video—after two or three more meetings, Penniman grew to trust Abramoff. He introduced him to United Republic CEO Josh Silver and got him involved in drafting ethics legislation.

“Jack is in this for all the right reasons,” Penniman says. “He really cares.”

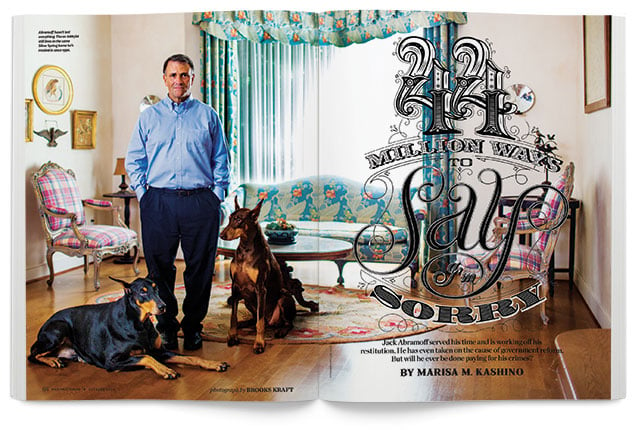

As Abramoff tells it, he developed his interest in government reform while serving time in a minimum-security prison in Cumberland, Maryland. He spent 31/2 years there, from November 2006 until he was released to a Baltimore halfway house in June 2010. He now lives in Silver Spring with his wife, Pam. He’ll be on probation until the end of this year.

While incarcerated, Abramoff read about the 2007 Honest Leadership and Open Government Act, which was passed in response to his crimes with the aim of making lobbying and political contributions more transparent. During walks around the prison’s track, he considered how “baseless and useless” many of the changes were and how easy it would be to get around them.

He says he thought: “If I believe that this system is not the best system, maybe what I need to do, instead of going away [after prison]—which is the easy thing to do—is to unfortunately put myself out there again.”

Abramoff’s friends, however, say that for him, going into hiding would have been the real struggle. “That wouldn’t be his first choice,” says Larry Latourette, who was managing partner of the firm then called Preston Gates & Ellis, now K&L Gates, when Abramoff was a lobbyist there. “He’s up for a challenge. He’s running in the red all the time.”

Latourette has stood by Abramoff; few other former colleagues have.

Many who knew Abramoff in his past life view his reform efforts with skepticism. I could almost hear some of them rolling their eyes on the other end of the line when I called. A couple of them sighed loudly when I explained what I was working on. One suspected I was just a pawn in Abramoff’s comeback strategy, asking if he was “pushing” me to do the story. (For the record, I approached Abramoff for this article, not the other way around.)

“Time will tell whether Jack’s doing this to get a seat at the big-boy table again in Washington,” says Neil Volz, who worked with him at Greenberg Traurig. “He likes to win. He wants to engage in politics in probably the only issue that he currently can—and win.”

• • •

Inside a radio studio in Rockville, Abramoff sets a giant glass mug of crushed ice on his desk, to the side of the microphone. The ice glistens under the lights as he approaches his 11th hour of fasting, near the 5 pm start time of Jack Abramoff.

Today is the Tenth of Tevet, a Jewish fast—not even a sip of water is allowed—that ends after sundown. Which means Abramoff must fill an hour of airtime on a bone-dry throat.

Abramoff decided at age 12 to become an Orthodox Jew, unlike his parents, who he says kept their faith only “superficially.” It was an early example of his distaste for doing anything halfheartedly: “I decided that if I was going to be Jewish, I was going to be religious.”

He landed the ill-fated radio gig while on his book tour. He promoted Capitol Punishment on shows produced by Premiere Networks, such as The Sean Hannity Show, catching the attention of the company’s executives, who offered him his own time slot.

Now, though, the studio feels lonely. His producers aren’t on-site; they communicate with him from LA over headphones. But while no one’s around and it’s a Sunday just before Christmas, Abramoff is dressed for work, in gray slacks and a blue button-up.

He leans in as his intro music starts. Then: “We’re live from Washington, in the wake of another Redskins victory!” One sentence in and he already struggles, muting the mike while he coughs. The ice slowly melts.

Gun control is today’s first topic. The shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary happened nine days ago, and there’s talk in Congress of reinstating a ban on assault weapons.

“I’m a conservative and a libertarian and somebody who doesn’t want the government controlling people,” Abramoff tells his listeners.

During a commercial break, he pours iced tea from a turquoise Thermos into the mug. Fifteen minutes until sundown. He mentions he’s fighting with one of his twin 19-year-old daughters.

“Well, she’s 19,” I offer.

“Yeah, going on seven at times,” he says, his voice taking on a surprising edge. Maybe it’s the low blood sugar.

During the next segment, he discusses a column by Ann Coulter advocating for the “concealed carry” of handguns. “People are at risk in these gun-free zones,” he warns the audience.

The first commercial since sunset arrives like a life raft. Abramoff raises the mug to his lips and gulps down the tea.

He takes an on-air guest after the break. A ProPublica reporter has called in to discuss how few presidential pardons have been granted in recent years.

“I was a victim, too,” Abramoff tells the audience. “I applied for a commutation and didn’t get one.”

That’s right. A victim.

• • •

What Abramoff initially went to prison for was unrelated to his lobbying. In 2000, he and then-business partner Adam Kidan bought SunCruz Casinos, a fleet of gambling boats, and were later found to have defrauded lenders in the transaction. Abramoff was two years into his jail term for that deal when he was sentenced to an additional four for his corrupt lobbying practices.

The details are Beltway legend: To expand his influence on the Hill, Abramoff lavished politicians and their staffs with free sushi and booze at his Pennsylvania Avenue restaurant, Signatures. He hosted them in luxury boxes at Wizards, Orioles, and Redskins games. He threw fundraisers for Republican lawmakers and directed hefty contributions from his clients to the pols who did them favors. And he infamously whisked Congressman Bob Ney and others away on a private jet to Scotland to play golf at St. Andrews.

Abramoff concedes he had “a flaw in my philosophy”—that it was more important to win for clients at any cost than to play by the rules and lose. During a lecture he gave last November to an American University political-science class, he amped up the theatrics while responding to a young woman who asked why lobbyists shouldn’t be allowed to operate as he did.

“It’s not what this country should be,” Abramoff said, his voice rising. He locked eyes with the student: “I’m ashamed of it.”

But prior to that impassioned answer, he had captivated the class with an account of how he outfundraised a congressman who had blocked a bill just to “screw” one of his clients. In that moment, he sounded every bit the brash, Backroom dealmaker—the caricature many in Washington still believe him to be.

The drive to finance the opposing campaign, Abramoff explained, was his way “to send a message to every member of Congress.”

Try as he might to appear humbled, Abramoff can’t always keep his ego out of the way.

He peppers apologies for his past with justifications for his actions and anecdotes meant to show he’s really a good person. Like his tale in Stamford about bonding with the prosecutors—intended as heartwarming, but weirdly narcissistic to claim that the prosecutors’ sympathy for him would win them favor in heaven. Or when, during our first meeting, he stressed that he tried to return the check of a lobbying client whose mission he came to view as impossible—casting himself as more Boy Scout than powerbroker.

Or, most notably, how while admitting to “crossing the line” as a lobbyist, he defends the staggering fees he billed clients, including the $2.4 million the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians shelled out for just six months of lobbying work and the $4.2 million he charged the El Paso Tigua. He insists he saved the tribes more money than he charged.

• • •

Abramoff gets cagey when discussing the $44 million in restitution he’s been ordered to repay the American Indians who hired him.

One of the most despicable plans he and his former partner, Michael Scanlon, were accused of orchestrating was taking money from one tribe to shut down the rival El Paso Tigua’s Speaking Rock Casino, then turning around and convincing the Tigua to hire them—for that $4.2-million fee—to get the Speaking Rock reopened.

Abramoff insists it didn’t go down that way. He says Texas state authorities put into motion a plan to shutter the Tigua’s casino long before Abramoff was in the picture.

The Tigua don’t buy it. Their lieutenant governor, Carlos Hisa, proffers a warning for anyone who believes Abramoff is a changed man: “Once a Judas, always a Judas.”

When I ask Abramoff if he feels the restitution is fair, he first says, “Whether I feel it or don’t feel it, that is the situation.” Pushed to answer the question, he refuses: “That’s not an area I want to get into.”

Tom Rodgers, a member of the Blackfeet tribe and a lobbyist who represents American Indians, compiled the initial evidence that sparked the investigation into Abramoff.

He says it disturbs him that Abramoff is again in the spotlight: “In a perfect world, I wish he would go to one of our poorest reservations and do service in silence, without cameras, without writing a book. Simply serve those who have the least.”

Instead, after a long day, Abramoff pulls into a quiet enclave of stately homes. Then turns onto a private drive hidden from the street by lush trees and shrubbery. Then strolls through a grand, arched entryway. Then lays his head down inside the same Silver Spring mansion he’s owned since 1996, where a pair of loyal Doberman pinschers keep watch. Despite the eight-figure tab hanging over him, outwardly Abramoff doesn’t appear to suffer too badly.

When he’s not in Washington, he’s likely in LA or New York working on his TV and book projects. By his own admission, he has overindulged in those cities’ multitude of gourmet kosher restaurants—so much so that he put himself on a diet in April to lose 60 pounds.

Not that there’s anything wrong with Abramoff’s living and eating however he chooses. He has served his time, and he continues to abide by the conditions of his parole.

It’s just that the optics are slightly discomforting—particularly when you remember some of the details that came to light during the investigation. Such as the e-mails in which he referred to his American Indian clients—the ones forking over piles of cash—as “troglodytes,” “morons,” “monkeys,” and “idiots.”

Abramoff tells me—as he has told many reporters—that the e-mails were “jocular, immature, and stupid.” But he denies they were racist. He also likes to emphasize that only 50 of his 850,000 e-mails were damaging.

Maybe that’s a fair point. But ask yourself: How often do you refer to members of a minority group as monkeys?

There is one place Abramoff still pays for his wrongdoing: the golf course. Prison ruins a handicap.

Before the scandal, he belonged to the exclusive Country Club at Woodmore, nestled in a gated community in Prince George’s County. But on this swampy Sunday afternoon in June, he warms up at Northwest, a public course about 15 minutes from his house.

His longtime golf buddy, Howard Sabrin, an electrical engineer who goes to Abramoff’s synagogue, joins him. Sabrin designates Abramoff as scorekeeper. The pair have played together for 17 years—they say never for money. Abramoff apparently reserved the real competition for more powerful friends; he once played a round with Mike Scanlon, wagering as much as $10,000 a hole.

Abramoff and Sabrin definitely don’t look like high-rollers. Both wear oversize polos. Abramoff has at least tucked his in. His olive-green shorts sag under his belly. Despite the nearly 90-degree heat, he insists on carrying his clubs for all 18 holes for the exercise. Sabrin, meanwhile, secures his to a rolling cart.

It also happens to be Father’s Day, and as Abramoff prepares to tee off, one of his daughters calls to acknowledge the occasion. His voice warming, he calls her “sweetie” and thanks her.

Even though two of his children are in town, he doesn’t have plans with them today. He might see a movie with his wife later. But he says all five of his kids stuck by him through prison and continue to support him.

One son goes to Santa Monica College, a community college in California, where earlier this year he ran for student-body president. Asked by the school paper about his father’s past, he said: “I didn’t make those decisions, and that’s not what I stand for.” (Abramoff said his wife and kids “would not be amenable” to being interviewed for this story.)

One daughter goes to her dad’s alma mater, Brandeis, where she got scholarships and works to put herself through school. She’s the only one of Abramoff’s five kids to go to a four-year university. One son didn’t attend college; the others went to community colleges. This might be the other area in which Abramoff still pays for his crimes. He says it troubles him that he can’t do more for his kids: “Certainly, I would prefer to be able to write a check and have them all go to a private university.”

• • •

Abramoff kept a single envelope stuffed with family photos in his locker at Cumberland Correctional. That and a few books were the only personal belongings he was allowed.

With 48 men in his wing, crammed six to a 150-square-foot cell, Abramoff could barely stretch his arms without touching someone.

His cellmates did their homework, collecting articles about Abramoff before his arrival. “Celebrity” prisoners often have a rough go of it, but Abramoff says it was the staff, not the other inmates, who bullied him.

That’s not to say he got along with his cellmates, most of whom were in on drug charges. Their “obscene” music and cigarette smoking wore on him.

To pass time in jail, he poured himself into work. When he landed a job as a dishwasher making 12 cents an hour, he says, he scrubbed harder and longer than anyone else. He later scored a position as one of three clerks at the prison chapel.

As part of his duties, Abramoff taught Judaism classes to inmates. He wanted a Torah scroll and asked two Jewish women who often visited the jail to deliver a letter to a rabbi requesting one. The move counted as circumventing the regular mail system, and the guards threw Abramoff into solitary confinement for 72 hours as punishment.

While in “the hole,” all he could do was pace and pray to get out. He worried he was going insane: “It’s cold. The lights are on. It’s noisy because the other loonies are screaming. You don’t know what time it is.” Abramoff holds his thumb and index finger about an inch apart. “Your bed’s got this much foam on it. No pillow.”

But compared with the other prisoners, Abramoff counts himself lucky. He never fell into depression, and his family didn’t abandon him.

Larry Latourette, the former managing partner of Preston Gates & Ellis, who remains a friend, carpooled with Pam Abramoff to see her husband. He says the couple seemed “warm and loving” during the visits.

Congressman Dana Rohrabacher, a Republican from California and the only national politician who continues to support Abramoff publicly, also visited. The pair first met while Rohrabacher served in the Reagan White House, and Abramoff, as chairman of the National College Republicans, worked with the administration on combatting communism.

“Jack has made his share of mistakes,” Rohrabacher says. “But I believe, knowing him the way I do, that Jack is a superior human being and someone who, if given a chance, will prevail.”

• • •

While he was locked up, Abramoff says, all he wanted was to be with his family.

But now, between his speeches about government reform and meetings in New York and Los Angeles for his TV and book projects, he’s often away. From January to March of this year, for instance, he looped back and forth to New York, Atlanta, and California, never spending more than a week at home.

I ask how his wife handles his absences. “Our whole marriage, I’ve been away,” he says, noting that his lobbying career also kept him on the road for fundraisers and client meetings. “We don’t like it, but I guess we do tolerate it.”

Abramoff is counting on his potential television shows, as well as his plan to create a series of books and movies like The Lord of the Rings, to regain his fortune.

He weighs his future prospects while drinking tea in a darkened corner of a hotel restaurant. We’re on K Street, but the power elite doesn’t dine here at the budget-friendly Sheraton Four Points. This is tourist territory—meaning Abramoff risks little chance of being recognized, something he’s always conscious of.

“I’m hoping that as many projects as possible come to fruition and I’m able to, at some point, pay off the restitution and get it behind me,” he says.

Abramoff moves comfortably in the entertainment world, where he claims “there’s a panache to being a rogue felon.” His dad was a successful businessman who moved the family from Atlantic City to Beverly Hills when Abramoff was ten. Abramoff got used to seeing stars around his neighborhood.

“When you grow up with that, it’s not a big deal,” he says. “Robert Young, okay? He was two doors down. Kenny Rogers was on the corner. Danny Thomas was, for a while, on the other corner. Gene Hackman was the next block over.”

In the 1980s and ’90s, he took a turn as a movie producer, making Red Scorpion, an action film about fighting communism, and its sequel, Red Scorpion 2.

Now his TV project that’s furthest along is a reality series about how Washington works. With Abramoff as host, each episode would explore a different topic, such as how someone becomes an ambassador. Lions Gate is backing the show, but whether it ever becomes more than a concept is anyone’s guess.

“I don’t know if it’ll happen or not. It’s possible,” Abramoff says. “It’s harder [to make money] now. I have more shackles on these days.”

• • •

As he walks on the golf course, hunched under the weight of his bag, feet squishing into grass spongy from a week of downpours, it’s hard not to see Abramoff as a burdened man.

He approaches the ninth tee, a bead of sweat clinging to the tip of his nose. His driver cracks against the ball and Abramoff yells, “Crap!”—the closest he comes to cursing, at least in public. His ball flies far to the right of the fairway, disappearing into some trees.

Though his game’s been inconsistent, Abramoff has kept up a sense of humor, making fun of himself and always offering his buddy praise for a good shot. Now his face falls.

He takes off 20 yards ahead, shoulders slumped, working hard under the hot sun and the heft of his bag. He’s on a mission to find the ball, but perhaps he also wants some distance. He stops in front of a massive tree, where the ball rests, and silently considers how to get it around the thick trunk and out of the rough. He swings.

The ball hits the cart path, bounces, and lands all the way up on the practice putting green by the clubhouse. Abramoff presses his lips together. “Not good, not good. Oh, my,” he mutters.

Then he springs back to life. His grimace morphs into a smile as he calls out to his friend: “Hey, Howie! Can I hit it into one of those holes instead?” He points to the practice green.

Howard Sabrin laughs, takes his shot, and gets his ball within a foot of the hole. “Showoff!” Abramoff yells, still smiling.

Earlier in the afternoon, he had noted that Sabrin was the much better player, especially because jail kept Abramoff from practicing for so many years.

But he manages to stay ahead of his friend the whole round. On the fifth hole, he drove the ball low to the ground, avoiding—he says by pure luck—the quickening wind. That ball sailed fast and straight.

At the end of the day, Abramoff wins by ten strokes, the first time since his release from prison that he has beaten Sabrin. It’s his big comeback.

Or maybe not.

Maybe Abramoff asked Sabrin to throw the game because I was there. Maybe he exaggerated how much of an underdog he was to begin with. Or maybe he somehow fudged the score.

The truth is, he probably didn’t do any of those things. But because he’s Jack Abramoff, you can’t help but wonder.

Marisa M. Kashino can be reached at mmkashino@gmail.com.

This article appears in the October 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.