Creigh Deeds never was one to give long speeches.

He wasn’t the type of legislator who needed to be heard on every issue. But on February 10, Deeds rose from his desk on the floor of the Virginia state Senate and asked his colleagues to listen. “I’m not going to apologize for talking a couple of minutes about this bill,” he said.

Many of Deeds’s fellow lawmakers couldn’t believe he was back at work. Just three months earlier, his 24-year-old son had exploded in psychiatric rage, stabbed Deeds nearly to death, and killed himself with a shotgun. Thick pink scars now sliced the 56-year-old senator’s face from forehead to chin, a permanent etching of his son’s last day alive.

Gus Deeds was the senator’s only son, his “perfect son”: a hunting and fishing buddy, a guy who picked his banjo on the campaign trail with his dad, high-school valedictorian, the kid everyone looked up to.

“I’ve heard from so many people that have had similar experiences to what I went through, and a lot of them live in your districts,” Deeds told his colleagues. “Maybe they don’t get attention because they aren’t state legislators, but similar situations happen almost every day.”

Before the attack, Deeds was a serious but friendly figure inside the Capitol. After 23 years there—first as a member of the House of Delegates, then as a state senator—he’d earned a reputation as an agreeable pragmatist, a Democrat who supported gun rights with such enthusiasm that the National Rifle Association endorsed him. Deeds wrote “Megan’s Law,” which established a public registry for sex offenders, and he cleaned up the Kim-Stan Landfill, a 24-acre pit of industrial waste that leached hazardous sludge into the wetlands. Colleagues enjoyed working with him.

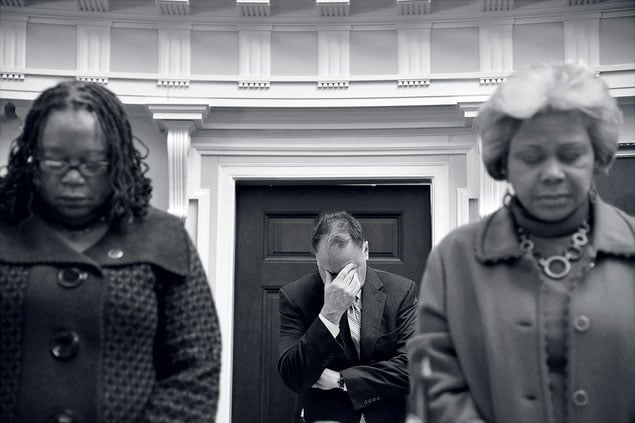

After the attack, Deeds’s presence in the Capitol was unsettling. Fellow lawmakers didn’t know what to say. For Deeds, there was only one reason to show his face in Richmond. He wanted to protect others from the horror he had lived. “I implore you to pass this bill,” he said.

Richmond had never felt like this, never witnessed a political crusade like Deeds’s. Tragedies have long been catalysts for new laws, but rarely does the victim write the legislation himself. “I’ve learned over my time here not to take [politics] personally,” Deeds told the Senate. “But, honestly, I can’t do that here. I can’t do that with this bill.”

• • •

Creigh Deeds learned politics from his grandfather, a local Democratic-committee chairman who helped raise him on a hog-and-cattle farm in Bath County, a sliver of verdant Appalachia on the West Virginia border. In the New Deal era, President Franklin Roosevelt’s Rural Electrification Act had made the family’s farmhouse the first in the area with electricity. It was an indelible lesson for Deeds about the government’s potential to improve lives.

Yet even as he scaled the highest steps in Richmond, Deeds remained the old-fashioned country lawyer from the Allegheny Mountains. He flipped burgers at political events, marched in local parades, kept a mule named Harry S. Truman.

“He’s part of the family,” says Anne Adams, publisher of the local newspaper, the Recorder. Bath County, population 4,616, is a longtime Republican stronghold, but Deeds had never lost an election there.

Still, hometown senator-for-life wasn’t his highest aspiration.

In 2005, Deeds ran his first statewide campaign, for attorney general. Though his Republican opponent, Bob McDonnell, spent twice as much money on the race as Deeds did, the candidates were neck and neck on Election Day, and long after the polls closed there was no clear winner.

Election officials recounted all 1.9 million ballots, and six weeks later a Richmond circuit court certified a 360-vote victory for McDonnell. It was, at the time, the closest election in Virginia history.

The loss didn’t deter Deeds. He believed he had more to offer Virginians, and two years later he launched a bid for the office he’d always wanted: governor.

From the start, it was an insurgent affair. Without the budget for flashy consultants or big media buys, Deeds crisscrossed the Commonwealth in his beat-up Ford Explorer. He hung his suits from a pole in the back. Instead of hotels, he crashed at supporters’ homes.

Deeds never had the game-show-host charisma of more polished candidates. “You put him in a room with 500 supporters and you’ll find him in the corner talking to the service staff,” says Joe Abbey, his then campaign manager. When aides set up a Twitter account to amplify his message, Deeds—a music lover—used the social-networking service simply to announce what album he was listening to.

As primary day approached in 2009, the Deeds for Governor campaign barely had a pulse. He was outspent by his higher-profile opponents from the Washington suburbs and ignored by the media, polling in a distant third place. Many voters couldn’t even say his first name. (It’s pronounced “cree.”) Then came a surprising endorsement from the Washington Post. Abbey’s team scrambled to have it plastered onto every yard sign and TV commercial they could afford, and three weeks later Deeds clobbered opposing candidates Terry McAuliffe and Brian Moran by a margin of two to one.

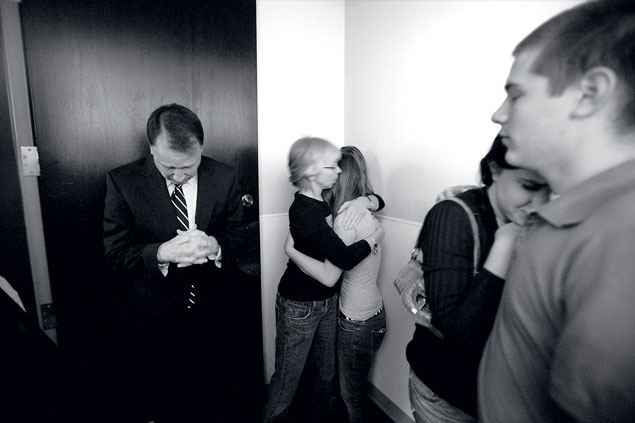

On primary night at the Omni Hotel in Charlottesville, Deeds threw away his concession speech, hugged his wife and children, and beamed from the podium before a giddy crowd of supporters. By the end of his victory address, he was choking back tears.

“Only in America, only in the Commonwealth of Virginia,” Deeds said, “can a mother, who still works as a mail carrier in Bath County, send a son off to college with four $20 bills in his pocket—that was all—and have her son be standing before you as the Democratic nominee to be the next governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia.”

The euphoria was about to fade. Deeds was once again facing McDonnell, the telegenic Republican who had already beaten him for attorney general. The grind of the campaign—one stump speech after another, weeks away from his family—would soon take its toll.

Deeds’s wife, Pam, called his campaign manager with a suggestion. “I think Gus wants to take a semester off and campaign with Creigh,” she said. “What do you think?”

• • •

Gus had a closet full of Creigh Deeds T-shirts and grew up attending his father’s political events. “Creigh was always very proud of Gus, and Gus was always very proud of his dad,” says Gus’s friend Will Trimble.

Pam and Creigh Deeds had four kids; Gus was the third. Like his father, he spent his childhood exploring the Bath County wilderness, paddling kayaks down the Cowpasture River and grilling hot dogs over campfires. His magnetic personality turned classmates into friends, while his insatiable mind—Gus was into everything from Gaelic history to Arab linguistics—made him the top student in his high-school class. “I looked up to Gus so much,” longtime friend Alex Haney says.

Music is what really animated Gus. He played trombone in his high school’s marching band and entertained friends by bursting into unscripted song. He taught himself the piano and harmonica before falling for clawhammer-banjo music, friends say. He built his own banjo out of metal scraps.

After enrolling at the College of William & Mary in the fall of 2007, Gus made the dean’s list, composed songs, and joined the Appalachian-music ensemble. “He was really proud of his Appalachian background and loved to demonstrate that music,” says Brian Hulse, Gus’s college adviser.

Demands on Deeds’s time meant he and his son were often apart, but he did what he could to stay connected to Gus through the interests they shared: the outdoors, music, and the Cincinnati Reds. (Deeds had become a fan as a boy because the Reds were the only team whose broadcasts reached his radio in Bath County.) Tony Walters, a close friend of Gus’s, remembers Deeds calling one night to check in on his son. “Talk to you later, Dad—I love you,” Gus said at the end of the conversation.

After hanging up the phone, Gus turned to Walters. “You know,” Gus said, “it’s really important to tell your parents that you love them. I’m not ashamed of telling my father that I love him, and he does the same to me.”

Deeds’s staff loved the idea of Gus’s taking a semester off college and campaigning with his dad in the 2009 governor’s race. “Get him in the car right now,” Abbey told Pam.

Gus plucked his banjo at rallies, shook hands with supporters, and watched his father’s speeches with visible admiration. “He was kind of the life of the party,” says Kevin Mack, a Deeds campaign strategist.

Gus also kept the candidate smiling during long car rides from one end of the state to the other, even in the fall of 2009 when McDonnell opened up a double-digit lead over Deeds. “Having Gus around lifted Creigh at a time when, Lord knows, he didn’t want to be talking to a staff that kept telling him bad news,” Abbey says.

The final tally on Election Night was worse than anyone imagined: McDonnell had beaten Deeds once again, this time by 17 points.

In just five months, Deeds had gone from underdog hero to national embarrassment. “It was tremendously difficult for him,” a former campaign aide says. “He lost to the same guy twice. It was basically the end of his aspirations for higher political office.”

After the loss, Deeds retreated to Bath County and disappeared from public view. “I think Creigh always felt like he let everybody down,” Mack says.

Three months later, he and Pam—his college sweetheart—divorced. According to the Post, Deeds told friends the relationship dissolved because for 20 years, his life in politics had kept him away from home.

• • •

Gus also returned to Bath County after the 2009 election instead of going back to college. That’s when friends began to notice a change.

It seemed minor at first. Gus might head home early from an evening out with the guys. Sometimes he seemed submerged in his thoughts. He stopped calling friends to hang out.

The behavior was odd but understandable. Gus had just watched his father get humiliated in a statewide election and his parents end their 29-year marriage. Friends figured he’d snap out of it.

“But after time went on,” friend Jim King says, “that kind of down, obviously depressed Gus turned into more of a manic Gus.”

In the spring of 2010, Gus drove from Bath County to the West Coast because “God told him to go see the Pacific Ocean,” Walters says. Although a regular churchgoer, Gus had always been willing to analyze his Presbyterian faith with an academic distance. Gradually, however, his convictions hardened into fanaticism.

“Soon everything revolved around this vision and this apparent open communication he had with God,” King says. “I distinctly remember him saying, ‘I am God, and God is me.’ ”

The behavior frightened Gus’s family, according to Walters. In the fall of 2010, they admitted him to a mental-health center near Charlottesville for a couple of weeks. “Neither his mother nor I wanted to accept the fact that our brilliant, beautiful, precious son was sick,” Deeds says.

Gus continued to struggle. He stopped taking care of himself, put on weight, and withdrew from friends. “He just had all these conspiracy theories, all these ideas that people were conspiring against him,” Walters says. Gus held down a dishwashing job at Virginia’s Homestead resort for a while, then left and moved in with his dad.

“He would dig these perfect rows in the garden with a shovel,” Deeds told the Recorder. “He would go on these coyote hunts at night with knives and spears.” At one point, Walters says, Gus built a bonfire and tossed his banjo into the flames.

• • •

It’s impossible to say what triggered Gus’s breakdown. Mental illness is caused by a mix of biological predisposition and environmental stress factors that vary from one case to another, says psychiatrist James Reinhard, former commissioner of Virginia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services. Deeds says he was told Gus was “somewhat bipolar, but not a classic case.”

“As parents, we continued to believe that we could get our son back,” Deeds says. “Friends and family assured me he’d grow out of it.” Yet while staying with Deeds, Gus acted “even more erratic” than before, his father says, and became suicidal. On the two occasions that Gus talked about killing himself, Deeds had him committed to psychiatric hospitals. The experiences gave Deeds a firsthand look at the state’s mental-health bureaucracy.

Virginia’s involuntary-commitment process begins when a magistrate judge issues a so-called emergency custody order, which allows police to detain the person of concern. The patient is then evaluated by the local Community Services Board, an administrative body for the state’s mental-health system. If the evaluator concludes that the patient needs hospitalization or treatment, it’s the professional’s responsibility to contact psychiatric facilities in the area and find an available bed. The whole process had to be completed within six hours, before the emergency custody order expired—otherwise, the patient would be released.

Both times that Deeds sought to commit his son, Gus was admitted to psychiatric facilities for two days, prescribed medication, and put under the care of a psychiatrist after being released. The system functioned as it was supposed to, just as it does 97 percent of the time.

Gus had more ups and downs. In the fall of 2011, when Deeds went back on the campaign trail in pursuit of another four-year term in the state Senate, Gus went along. This time he was distant and withdrawn, nothing like the charismatic force that staffers recalled from 2009.

Deeds “would say things like ‘My son used to be a dean’s-list student, and now he doesn’t know what he’s doing with his life,’ ” says Casey Sparks, deputy campaign manager for the 2011 race. “Being the great father that he was, he took Gus’s struggle so personally.”

In the months after Deeds won the race, Gus improved. He became more comfortable leaving the house and less volatile in social settings. In the summer of 2012, he got a job as a counselor at Nature Camp, in Virginia’s George Washington National Forest, where he had been a camper himself, and in the fall he returned to William & Mary.

He was stable but not the same. This wasn’t the Gus Deeds who had led friends on weekend camping trips or given goofy nicknames to his dad’s aides. “He went from being a guy I looked up to to a guy who I had to look out for,” Walters says.

In 2013, as another summer at Nature Camp came to a close, Gus seemed to regress, says Alex Haney, his longtime friend and a head counselor. He became paranoid and was suspicious of other counselors. “When we left camp, I kind of knew that something was off,” Haney says. “He was getting close to being back where he was.”

Gus returned to William & Mary last fall but then dropped out in October after venting on Facebook that his teachers had it out for him, the Recorder reported. He had stopped taking his medication.

Gus went home to Bath County just as Deeds and his second wife, Siobhan—whom he had married in 2012—were preparing to leave for Ireland to scatter her mother’s ashes. “I was panicked,” Deeds told the Recorder. “I felt I needed to get him some help, and I tried. I got him with a psychologist friend of mine.” Deeds also arranged for Gus to see a counselor while he was gone.

• • •

Deeds got back to Bath County on Saturday, November 16, to find things worse than before. Gus hadn’t been to see the counselor.

“I saw glitches in his behavior and had found his journal, and these things disturbed me,” Deeds told the Recorder. Two days later, he set about having his son committed for a third time.

Deeds got an emergency custody order midday on November 18, a Monday. According to a report by Virginia’s Office of the State Inspector General, a Bath County sheriff’s deputy picked up Gus around 12:30 pm and drove him to a nearby hospital, where Gus waited and waited for the Community Services Board evaluator to show up.

Thanks to a communication screwup and the 70-minute drive between the evaluator’s office and the hospital, Gus wasn’t seen until 3:45 pm, according to the inspector general’s report. The evaluator concluded that he should be hospitalized, but by then only two hours and 40 minutes remained to find him a bed before the six hours would expire.

The evaluator contacted seven nearby facilities looking for a bed. No one had room. Thirty minutes before the deadline, the evaluator called a hospital in Harrisonburg, according to the inspector general’s report. After two minutes on hold, the evaluator hung up and faxed in Gus’s paperwork. But the fax number was wrong, and the hospital—which had space for Deeds’s son—never received the request.

At 6:26 pm, the custody order expired and Gus was released.

He was silent during the drive home from the hospital and spent the evening at his dad’s house scribbling in his journal. “He had cut off everybody,” Deeds told the Recorder. “I might have been the last person he really trusted, and here I was trying to commit him.”

Deeds was outside feeding the horses early the following morning, November 19, when his son came up from behind and stabbed him repeatedly in the head and torso.

“I turned around and said, ‘Bud, what’s going on?’ ” Deeds told CBS’s 60 Minutes. “He just kept coming at me. I said, ‘Gus, I love you so much.’ I said, ‘Don’t make this any worse than it is.’ ”

Deeds was able to stagger to a nearby road, where his cousin spotted him and called for help. Gus, meanwhile, went back inside, took his father’s rifle, and shot himself to death, 19 hours after being taken into police custody.

• • •

After three days at the University of Virginia Medical Center in Charlottesville, Deeds returned home and read what Gus had written in his journal the night before he snapped.

“He had determined that I had to die,” Deeds told 60 Minutes, “that I was an evil man, that he was going to execute me, and then he was going to go straight to heaven.”

As the tragedy spiraled into a media spectacle, Deeds struggled to make sense of it. “I am alive so must live,” he said in Twitter and Facebook messages the morning he was released from the hospital. “Some wounds won’t heal.”

Swamped by condolences from his friends and associates, he also heard from people he didn’t know, everyday Virginians who had been similarly abandoned by the state’s mental-health bureaucracy.

Never again, he thought.

• • •

Deeds was “scared to death” about going back to the Capitol, as he put it later. But lying in his hospital bed, he couldn’t stop thinking about how to use his power to protect other families. When the legislature’s 2014 session began on January 8, Deeds returned to Richmond.

He kept to himself. Whereas in years past Deeds had taken meetings with anyone who showed up at his office, this time his door was closed even to good friends. He also asked colleagues not to recognize his arrival in any formal way. They expressed their condolences as only they could, by introducing bills aimed at reforming the state’s mental-health system.

Right now the system is a rickety patchwork of services administered unevenly throughout the state. Funding is cobbled together from federal, state, and local sources. “We’re kind of scraping by,” says Mira Signer, executive director of the Virginia chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

In truth, the system needs a wholesale restructuring. But the General Assembly didn’t have the appetite for that. Instead, Republicans and Democrats agreed to take a less ambitious approach and fix the gaps exposed by Deeds’s tragedy.

He and several colleagues stitched together three reforms into a single piece of legislation that came to be known as “the Deeds bill.” The measure would extend the emergency-custody-order period from six to 24 hours, create an online registry for real-time information on psychiatric-bed availability, and require state hospitals to admit emergency psych patients for whom no other bed could be found.

Typically, the lawmaker whose legislation is introduced first takes ownership of the effort, speaking publicly about the bill. Deeds wasn’t the first to file his proposals, but his colleagues decided that didn’t matter. “We wanted to stand behind him,” says Senator Barbara Favola, a Democrat who represents a Northern Virginia district. “We wanted him to carry the bill.”

Deeds took the measured approach he was known for, eschewing press conferences and interviews and limiting his remarks mostly to a handful of committee hearings. After his February 10 plea on the Senate floor, the bill passed without a dissenting vote.

“Nobody wanted to tell Deeds no,” says a senator who had reservations but voted in favor of the measure anyway. “I’ve lost a parent—I could only imagine losing a child.”

The House of Delegates was less sympathetic. More emotionally distant from Deeds and controlled by Republicans, the chamber voted the next day on a reform package that mirrored the Deeds bill—except for the custody provision.

That meant Deeds would have to compromise, something he wasn’t ready for.

“He’s got a job to do, and that’s to honor his son and to fix the system,” Joe Abbey, Deeds’s former campaign manager, says. “I will only say this: God help anybody who thinks they can prevent that from happening.”

• • •

A little after 9 am about two weeks later, John Jones was prowling the Capitol building for politicians. “It’s like hunting,” Jones said. “You’ve got to find your game and shoot it.”

The executive director of the Virginia Sheriff’s Association, Jones is one of the building’s regulars. “That man’s famous!” a secretary joked as he walked by. “The master!” said a senator by way of greeting.

Jones represents the state’s roughly 9,000 sheriffs and deputies—an active, influential lobby with roots in every voting district in the Commonwealth. Smart politicians keep their sheriffs happy, and on this day Jones was eager to discuss his most urgent concern: the Deeds bill.

Jones spotted Republican senator Jeff McWaters, who represents the Virginia Beach area. He darted toward him and got right to it: Mental-health reform was desperately needed in Virginia, and the Deeds bill just about nailed it. There was only one problem. By extending the emergency custody orders to 24 hours, as Deeds was insisting, the legislation would make local law enforcement responsible for people in the throes of mental breakdown for up to a full day.

Sheriffs can’t lock detainees in a cell because they haven’t broken any laws, Jones explained, yet their agencies had neither the staff nor the training to watch over the patients. In rural parts of the state, some counties had only two deputies on duty at a time, and if one had to babysit a mental patient all day, who was going to protect citizens from crime?

“I call it the ‘granny on the bench’ bill,” Jones told McWaters. “Because you’re going to have old ladies sitting in a sheriff’s office for 24 hours with no food and no water.”

Jones wanted McWaters to push fellow senators to go along with the bill the House had passed. It would increase the limit to eight hours, enough time for officials to find a bed without overburdening sheriffs.

“It’s a valid concern,” McWaters replied. “But is Creigh with you on this? Because he’s the guy.”

Jones explained that Deeds didn’t exactly see things his way. The truth was, Jones says, he had been tiptoeing around Deeds ever since the senator blew his stack at him after a committee hearing during which the lobbyist spoke out against the bill. (Jones says Deeds later wrote him to apologize.)

Jones asked McWaters to pass his concerns along to his colleagues, and the senator promised he would.

The politics of the Deeds bill were as touchy as any Jones could recall in his 37 years lobbying in Richmond. Everyone acknowledged the problem: In 3 percent of the roughly 1,400 adult cases each month, or about 42 cases, officials can’t find beds within the six-hour time limit, according to a 2013 University of Virginia study. While 42 cases a month is no epidemic, and while the majority of mental-illness victims aren’t violent, it takes only one volatile person to cause spectacular damage.

Lawmakers had tried to resolve this conundrum back in 2008, one year after a mentally ill Virginia Tech student shot and killed 32 people in one of the deadliest attacks in US history. In the end, because of opposition from Jones and the American Civil Liberties Union—which argued that lengthy detentions could violate constitutional rights—the legislature added only two hours to the then four-hour window.

In any other year, Jones and the sheriffs probably could have counted on backup from Virginia’s mental-health advocates. Though some had been clamoring for longer emergency custody orders for years, they were stunned by Deeds’s request for 24 hours. In their opinion, that was far too long. Strapping detainees to gurneys in sheriffs’ offices for hours on end “makes them worse,” says Bonnie Neighbour, executive director of the nonprofit VOCAL (Virginia Organization of Consumers Asserting Leadership).

But the advocates felt constrained by the outpouring of sympathy for Deeds in Richmond. Even if his bill was bad policy, opposing it could come off as insensitive and possibly weaken the advocates’ political capital over the long term. So they kept their concerns largely to themselves and left Jones to fight the 24-hour provision by himself.

“All these other groups are sitting back and letting me do this,” Jones told me. “I don’t care for that, but there’s not a lot I can do about it.”

After saying goodbye to Senator Mc-Waters, Jones stalked the building for other ears to bend. In the corridor outside Deeds’s office, young staffers of other lawmakers bounced forward to greet constituents, and secretaries traded jokes with passers-by. Deeds’s door was closed. Jones looked that way and nodded. “Let’s not go in there,” he said.

• • •

For three years, Deeds had worried that Gus would end up homeless or in prison. His ex-wife worried about Gus’s fixation with knives. At one point, Deeds convinced his son to let him hold onto the knife Gus was making. Deeds stowed it under the seat of his truck, never imagining Gus would become violent.

After the attack, Deeds’s second wife urged him to see a counselor. He promised he would, but focusing on his bill felt like the best therapy. As talk of the two chambers having to meet in the middle on the custody provision filled the Capitol in late February, Deeds held his ground.

No one saw the logic in his position. His own proposal, after all, guaranteed that anyone in emergency custody would get a psychiatric bed no matter how many hours had elapsed after a judge issued the order. What was the point of having a sheriff watch over a patient for up to a day beforehand?

Partly, his stance was strategic. Deeds felt the extra time was an important safety net to his other reforms, and he saw no reason to back down unless it looked like he had no other choice.

But his insistence, it seemed, wasn’t just about policy. Gus’s attack on him had been 19 hours after the sheriff picked Gus up. For a long time, Deeds just wasn’t ready to let go of a provision that, if it had been in place last November 18, might have saved his son’s life.

Days before the General Assembly adjourned in early March of this year, the House still wasn’t relenting. Deeds had a decision to make: He could go along with their eight-hour law or keep pressing for 24 hours, potentially killing the whole package.

Deeds knew what it was like to finish second, how it felt to lose. Compromising on the bill wouldn’t amount to the all-out win he’d hoped for, but it wouldn’t be a loss, either. If he gave in, no one in Virginia who needed an emergency psychiatric bed would be denied one like Gus was.

On the last day of the session, a Saturday, Deeds stood again on the Senate floor and asked his colleagues to approve the House’s eight-hour limit. The bill passed both chambers unanimously.

After the final gavel sounded, Deeds slipped downstairs and out of the building. It had been a frigid week in Richmond, but today was springlike. “It’s a good start,” he said, his eyes squinting in the sun.

Deeds followed the crushed-stone path away from the Capitol, waved goodbye to the security guards, and headed back home to the mountains of Bath County.

Staff writer Luke Mullins (lmullins@washingtonian.com) last wrote about the chef who took down former Virginia governor Bob McDonnell.

This article appears in the May 2014 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)