Among the many revelations about bungled White House security laid out in recent days by the Washington Post’s Carol Leonnig, few are as jarring as the tidbit about the Secret Service’s initial assessment of the November 2011 incident in which a gunman fired a semiautomatic rifle at the presidential residence:

“By the end of that Friday night, the agency had confirmed a shooting had occurred but wrongly insisted the gunfire was never aimed at the White House. Instead, Secret Service supervisors theorized, gang members in separate cars got in a gunfight near the White House’s front lawn — an unlikely scenario in a relatively quiet, touristy part of the nation’s capital.”

During a week when the Secret Service has been flayed by public officials and the media, it’s worth adding this to the bill of complaints: This theory betrays a baffling ignorance of the city where the agents work. To note this isn’t to make another one of those poor-pitiful-me hometown gripes about how federal types ignore the locals. If you’re in charge of protecting a guy who lives on Pennsylvania Avenue and periodically moves around the city, being an ignoramus about the environs represents a professional breach.

A gunfight near the front lawn would be where, exactly? The steps outside of DAR Constitution Hall? Not impossible, but highly implausible. As Leonnig notes in the same story, the Secret Service can’t depend on the Metropolitan Police Department’s ShotSpotter technology—the nearest gunshot monitor is about a mile away—but of the parts of the District that are observed for weapons fire, the four plots closest to the White House complex each recorded one incident between 2009 and 2013.

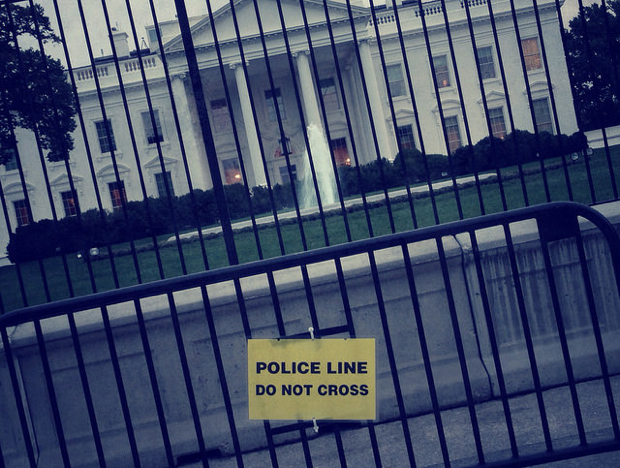

The area immediately surrounding the White House—historic hotels, museums, other heavily fortified government buildings—is one of the lowest-crime parts of the city. The area would, on paper, get even safer if the response to last month’s White House invasion by a man who climbed over the fence and managed to dash deep into the building before being stopped, is to fatten up the security bubble. Ironically, the security bubble itself may be part of the problem when it comes to agents being able to ignore their surroundings. Alas, the Secret Service’s first reaction to the latest revelations would make that worse.

Every instance of the White House restricting more turf from the public only exacerbates the nettlesome relationship between the presidential bubble and the city that surrounds it. Pennsylvania Avenue was closed off in 1995 after the Oklahoma City bombing; E Street, Northwest, followed after 9/11. The Secret Service actually staged a public forum in July 2013 raising the possibility of re-opening the two blocks of E Street south of the White House to bicycle traffic, but the matter hasn’t been touched since.

The biggest lesson the Secret Service struggles to latch onto in the District is that federal government police agencies need to be more cognizant of the fact they operate inside a city with 645,000 non-term-limited people. While veteran MPD officers tell Washingtonian that DC cops and officers working for the Secret Service or US Park Police share lots of information, there’s a fundamental difference in the types of police work they perform. Local cops patrol street corners and walk beats, federal cops—especially Secret Service officers on presidential detail—secure perimeters. Delroy Burton, the head of the union representing MPD’s rank-and-file officers, says expanding the buffer around the White House would be the wrong response.

Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton amplified Burton’s caution in her testimony Tuesday at a House Oversight hearing on the September 19 incident in which suspected intruder Omar Gonzalez made his way over the fence and into the White House. “Particularly troubling in light of such unanswered questions would be a rush to quick fixes such as suppression of public access to the area around the White House without a thorough investigation,” she said.

Yet the White House’s misunderstanding of its neighborhood runs deeper than just the past few years. In 1989, President George H.W. Bush gave a now-infamous press conference in which he amped up the “War on Drugs” by holding up a bag of crack cocaine purchased by Drug Enforcement Administration agents in Lafayette Park. But even at the height of DC’s crack epidemic, Lafayette Park was no drug market, and it took some manipulation to get a dealer there. When the DEA called the dealer it would eventually nab for Bush’s prop, the suspect’s response was “Where the [expletive] is the White House?” the Post reported at the time. The police union scolded the White House and the DEA for mixing politics with law enforcement.

Burton is hardly insensitive to the White House’s concerns, though. District police are responsible for all presidential movements within city limits. The Secret Service works closely with MPD, but the partnership is tighter in the special operations division than it is with officers on street patrols.

The Secret Service clearly has issues to work out, as shown in Leonnig’s reporting this week, but its exposed faults seem more the results of human error. Responding by suddenly expanding the security bubble again—whether it’s more fences and Jersey barriers or bag checks on 15th Street—will only make the White House more alienated from the rest of Washington.

“They key is to educate the public,” says Burton. “When people understand what you’re doing and why you’re doing, it’s easier for them to accept some difficulty. But when they don’t know what you’re doing, it creates anxiety.”

Find Benjamin Freed on Twitter at @brfreed.