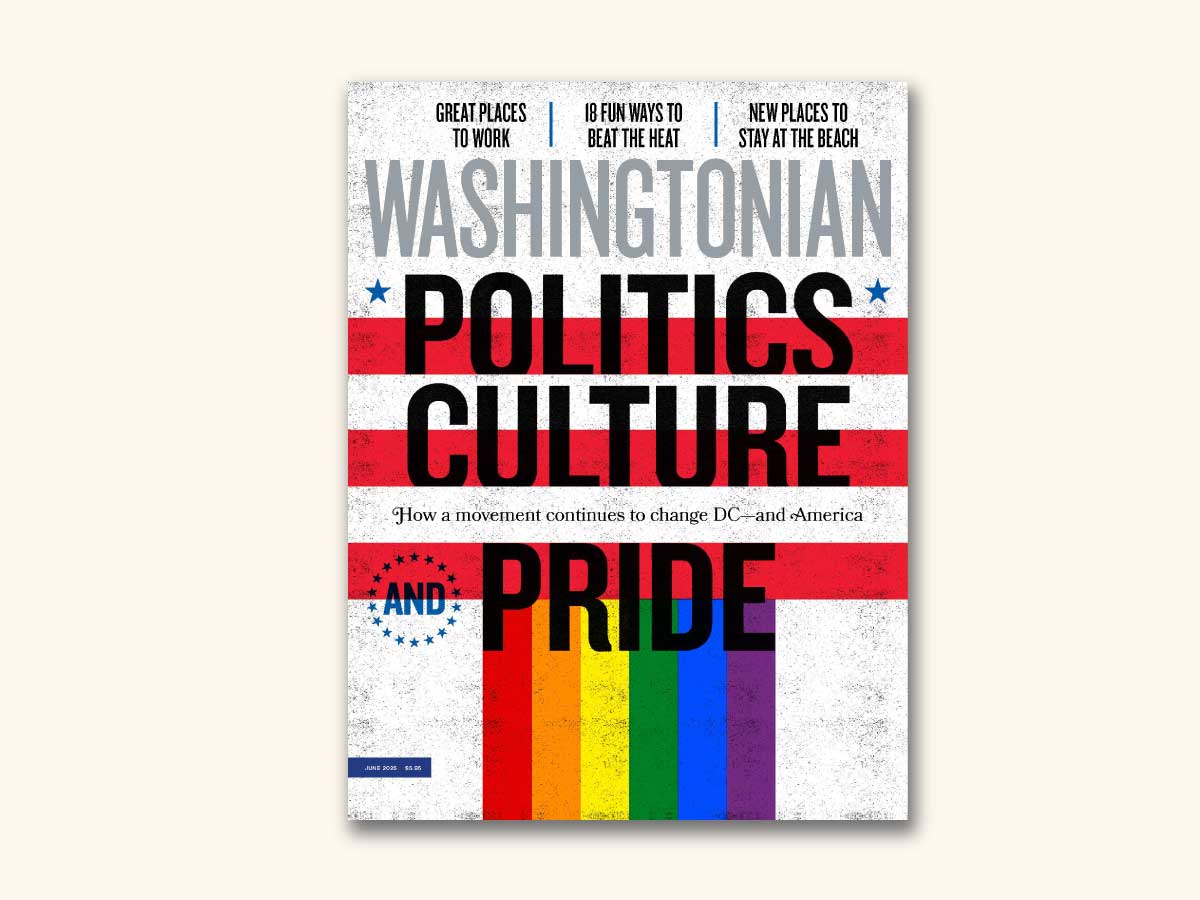

A window seat at Pearl Dive is one of the best perches on DC’s 14th Street. Photograph by Scott Suchman

>> See More Photos of Pearl Dive and Black Jack

In their first decade as restaurateurs, Jeff and Barbara Black opened three restaurants, all in Montgomery County, all comfortably low-key, all appealing to as broad a swath of the dining public as possible.

They launched Addie’s in 1995, enticing diners with a porch-fronted house set back from Rockville Pike and a menu rife with the comforts of fried oysters and shrimp ’n’ grits. (Jeff Black had just come from a nearly five-year tour of duty with Bob Kinkead of the downtown DC seafood destination Kinkead’s.) Black’s Bar and Kitchen followed three years later in Bethesda, serving first-rate seafood in a setting that didn’t feel like a splurge. With Black Market Bistro, which debuted in 2004 in Garrett Park, the Blacks cemented their status as masters of mood and place. You went to Black Market Bistro not just to eat, good as the food was—you went to be there. The space summoned the grand old houses of Charleston or New Orleans and had the curative effect of a weekend getaway.

Then the Blacks took an unexpected turn. The dining scene was becoming both more sophisticated and looser and more informal. New places sought to anchor themselves as neighborhood restaurants. The couple capitalized on both trends in 2004 by opening BlackSalt, a fish market/restaurant that residents of DC’s Palisades neighborhood flocked to, grateful that somebody had opened a glitzy restaurant there.

The Blacks followed that with a $2.6-million renovation of Black’s Bar and Kitchen, converting it from a shack where Jimmy Buffett might have drowned his troubles into a minimalist space where young things gather to sip expensive cocktails.

Pearl Dive Oyster Palace, which opened two months ago in Northwest DC’s 14th Street corridor, would appear to complete the transformation. No longer suburban restaurateurs selling an experience akin to a cable-knit sweater from Lands’ End, the Blacks have reinvented themselves as avatars of the new urbanity.

One night, the bar was thronged with thirtysomethings, the sound of laughter spilling out through the open window that fronts 14th Street. Inside, the noise rose to such a din that I had to lean in to hear my waitress rattle off the specials. It was a Monday.

Yet what makes Pearl Dive so good—if it’s not already the couple’s best restaurant, it’s easily the most fully realized—is that the Blacks have consolidated the lessons of restaurants 1 through 4.

If the oxidized sign out front and the weathered gray floorboards attest to a rustic-chic aesthetic, the basket of warm, buttery rolls and jalapeño-cornbread muffins is the embodiment of homey sincerity. The restaurant sits amid a six-block stretch of million-dollar condos, fashionable boutiques, and trendy bars and restaurants, but the early popularity of the place—and the easy banter among the cocktail-drinking, oyster-slurping denizens—suggests that it has connected with its community in a way its competitors haven’t. A neighborhood that would seem to have it all turns out to have been missing something: a neighborhood restaurant.

There’s something new in the mix, too: The Blacks have given us rootsy and sophisticated—now they’ve given us fun.

“Oh, my God, that’s good,” a woman at the table behind me squealed one night. She’d just downed an “angel on horseback”—a grilled bacon-wrapped oyster. I could hardly begrudge her the squeal. Smoky and salty, it had the essence of the fifth, hard-to-define flavor the Japanese call umami.

Even better, and also new to the Black repertoire, were a cocktail of seafood-studded salsa served in a margarita glass alongside fresh tortilla chips and a dish that once served as a staff meal at Addie’s: fried chicken that begins in a braise of chicken stock, ends in a deep fryer, and is that much more delicious for having been twice-treated. I’ve had fried chicken that was fancier and more fussed over, but I haven’t had fried chicken that was better.

The new tastes notwithstanding, the menu reprises dishes that have sustained the Blacks for 15 years. Seafood predominates, and the South, Louisiana in particular, is the reference point for many preparations. There are three kinds of gumbo, none of which you’d feel ashamed to show a New Orleanian; a rich, ruddy crawfish étouffée over buttered rice; an excellent po’ boy; and a Sunday-supper-style plate of crunchy fried shrimp that taste even better dipped in the eggy, house-made tartar sauce. A BLT topped with both fried catfish and a fried egg has no Southern antecedent that I’m aware of, but it sure tastes as if it does.

Danny Wells, the chef de cuisine, is a Blacks lifer, having worked his way up from the line at Addie’s a decade ago, and he understands that his job is closer to technical director than director: Stage a good show and disappear behind the scenes.

That may be why dishes that depend more on careful execution and coordination of multiple elements, like a lightly creamy seafood stew called What Cats Dream Of and several of the grill plates, are the least gratifying.

The star here is exceptionally fresh seafood—a testament to the Blacks’ fishmonger, M.J. Gimbar. His mandate? To combine his discerning eye and gift for tough talk to get good deals for the five restaurants. The ability to leverage high-volume buying into good deals is a benefit not only for the Blacks’ empire but for diners, too. Some may not think that a restaurant where dinner for two costs $75 is a good value, but Pearl Dive is. No dish costs more than $27. At lunch, the chicken goes for ten bucks. The shrimp plate—a full dinner with vegetable and potatoes—costs $19.

The dessert list is made up mostly of pies, including perfect renditions of Derby pie, crunchy with toasted walnuts and trailing whiffs of bourbon, and a tangy-sweet, creamy-light Key-lime pie. At a time when pie at a high-end restaurant often means a tiny, sculpted mound of cream and a pile of pulverized crust, it’s a relief to see a dish not flinch from what it is.

And how great is it to watch a roomful of people who are zealous about going to the gym, detoxing, and counting calories digging into thick wedges of rich, sweet pie?

Trendy space, homey plates. The Blacks have found themselves a new formula.

This article appears in the December 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.