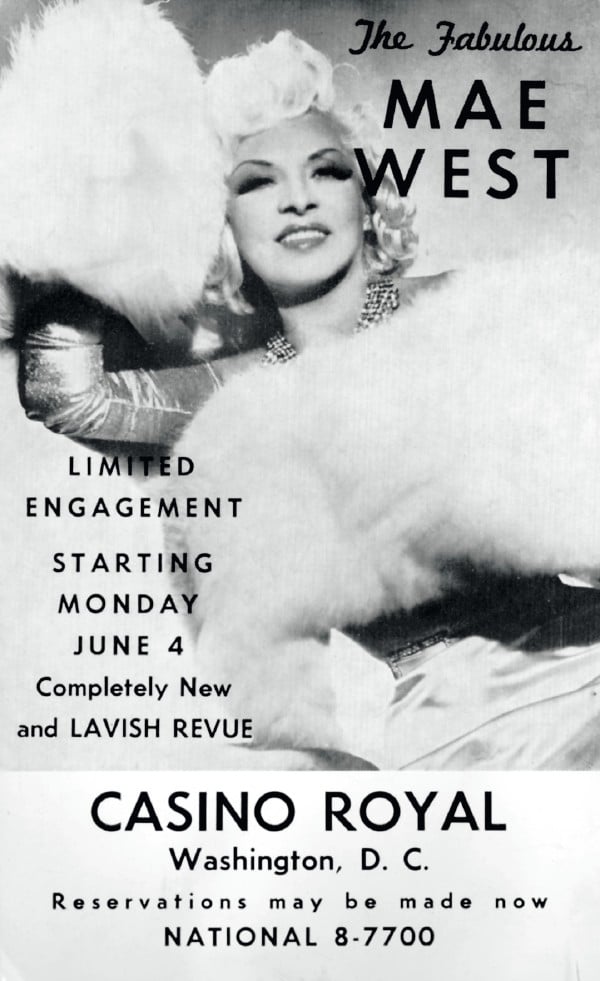

Mae West stood on stage, surrounded by muscle men. Her blond hair curled around her face. Her curvy body threatened to spill out of her dress.

As she joked and flirted through her act, men in suits and women in cocktail dresses sat at white-clothed tables that surrounded the stage. They were there for dinner, drinks, dancing, and a show.

The club owner’s secretary, a girl trying to make a good impression on her first day at the job, kept trying to catch a glimpse of the act from the office.

“I was kind of scared because I thought someone might yell if they saw me peeking,” says Doris Fortune, who lasted at the job for more than 19 years. “I thought they might make me pay for the show.”

It was spring 1956 at the Casino Royal, a nightclub in downtown DC. The city moved at a slower pace. Neither the Beltway nor the Metro yet existed to lure residents beyond the downtown area of shops and offices. Broadway tours stopped at the National Theatre, but there was no Kennedy Center, and the Warner showed movies. Charlie Byrd mesmerized jazz fans at the Showboat Lounge at 18th and Columbia, but Adams Morgan was pretty sleepy. The area now known as Penn Quarter boomed with retail, but there was no Verizon Center, and the area quieted down by dusk. So the Casino Royal, which took up the second story of 1401 H Street, Northwest, shone as a beacon of entertainment in the city.

“When you came across the 14th Street Bridge, you could see the glare from the lights,” says Ted Curtis, who did handyman work at the club and lined the roof with six-foot-high plywood horseshoes covered in 6,000 light bulbs.

The Casino Royal wasn’t the only club on the stretch of 14th known as “the Block” or “the Strip.” Across the street from the Casino was the Lotus, and down the block was the Blue Mirror. By 1960 two speakeasies would open on the first floor of the Casino. But the 600-seat Casino Royal was the largest and most popular, and it commanded the best performers. Leon Zeiger—owner of the Casino, Blue Mirror, and both speakeasies—was the man behind the area’s thriving nightlife.

Leon Zeiger was born in Philadelphia in 1918 to Jewish parents who had immigrated in the early part of the century. Zeiger’s father, Theodore, owned a dry-goods store.

“We were the only Jewish family surrounded by Irish Catholics,” says Barbara Gershkow, Zeiger’s sister. “I would go to my friends and help trim the Christmas tree.”

Early on, Zeiger showed signs of the charm and business acumen that would make him a successful club owner. Each day he delivered the Bulletin throughout Philadelphia on his bike, a job that during the summer kept him from going to the public swimming pools, which were open to kids only during certain hours.

“Well, he went to City Hall, talked to the mayor, and got a letter saying he could go to the pools whenever he wanted,” says Gershkow. “He always knew there was another way, that he could get what he wanted. But he always did it in a very nice way.”

In the early 1940s, Zeiger moved to Washington, working jobs in the federal government. Unsatisfied with the money he was making, he decided to open his own business as well. He eventually bought the Casablanca, a bar that was popular with servicemen. The Kit Mar, Gaslight Club, Blue Mirror, and other clubs followed.

In 1953 Zeiger bought Bamboo Gardens, a failing Chinese restaurant, and turned it into the Casino Royal. He renovated the interior but kept the staff. The club opened each night at 6 and served up three shows, with dancing in between, as well as both a Chinese and an American menu. Well-heeled patrons could choose items like pork chow mein or Maryland crab cakes, each 85 cents according to a 1956 menu.

It wasn’t the chow mein or crab cakes that drew patrons. From the opening act—Ella Fitzgerald—they came for the entertainers. Tony Bennett, Sophie Tucker, Johnny Mathis, Dinah Washington, Bobby Dar in, Chubby Checker, Peggy Lee, Frankie Avalon, and Nat King Cole all played the Casino Royal—some early in their careers.

“The first time we played Aretha Franklin, she was so nervous and wouldn’t sit on the stage,” says Doris Fortune. “She played piano, and she put it next to the stage and sat with her back to the audience.”

The shows typically featured a combination of acts—singers, dancers, and comics—with a headliner performing for the last 20 minutes of the hour.

During one of Mae West’s appearances, a new comic opened the show playing a preacher.

“Lee was in his office, and Mae West came in stomping mad and said, ‘I play the part of a whore. I can’t have a preacher opening for me,’ ” says Barbara Zeiger, Leon’s second wife. Leon told Mae West he’d replace the comic. “At the end of the week the kid’s still there. Lee was in his office, heard the audience laughing, and went out to see what was going on. Bob Hope had gotten up on stage with this young comedian and was doing a skit with him. The kid that annoyed Mae West was Andy Griffith.”

fortune’s job expanded beyond secretarial duties. She wrote ad copy, found housing for the entertainers, and secured props.

“Jerry Lewis played the Casino,” says Fortune. “Well, we rented a piano for him, and he broke it every single night. He used to stand on it and jump up and down on it. They wouldn’t rent us a piano anymore.”

Occasionally there were run-ins with the law. During fan dancer Sally Rand’s rehearsal, the DC vice squad came in, wondering what she was planning to wear during her act. She responded that she’d be wearing nothing but a Band-Aid and dared them to see it because she was so fast with the fans. The vice squad was just flexing a little muscle; Zeiger and the police got along.

“It was a time when money spoke,” says Ted Curtis. “We always had too many people on the floor. If we’d had a fire, it would have been a disaster. I’d see the officials go into Mr. Zeiger’s office and stay in there about an hour. They’d smoke some cigars, and everything would be okay. They’d all come and get their payoff.”

Things changed in the 1960s. TV made the salaries of entertainers “ridiculous,” Zeiger told the Washington Post in 1972. “We were paying Nat Cole $7,500 a week, our top price. Ed Sullivan started giving them $10,000 a night to do eight minutes.” In 1964 Jayne Mansfield was the last live act at the Casino. The club became a disco.

On April 4, 1968, violence erupted across the city after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

“I was at the Casino Royal, and I heard all this commotion,” says Curtis, who is black. “I went to the window and looked out. Coming down 14th Street were all these people. They were burning everything and taking everything. They threw bottles in some of the stores. My brother took some of the girls out of the Casino Royal and took them to Maryland.”

After two days the police and National Guard restored order. A dozen people died, and the city remained scarred for years. The Casino Royal remained untouched.

“The Casino Royal didn’t try and hold on to the politics of segregation,” says Curtis. “A lot of the clubs skirted the law. They wouldn’t let you in. The Casino Royal was a mixing pot. They didn’t care what color you were as long as you had a good time.”

The Casino Royal was one of the first clubs in the city to feature black people performing for a mixed crowd. It wasn’t a political gesture, says Leon’s son, David Zeiger. “He wanted to make a dollar. He wanted to be a success. He liked the color green.”

After the riots, “The Block” lost much of its luster and became a haven for drug dealers and prostitutes. People would break into the club when it was closed and steal furniture and artwork. Leon Zeiger spent more time at the Varsity Grill, a club he opened in College Park.

“You gave up after a while,” says Fortune.

Zeiger gave up officially in 1972, closing the doors after nearly 20 years. The tenants that followed included an adult bookstore and X-rated clubs. By the late 1970s, more than 30 adult bookstores and 40 bars with nude dancing had opened in DC, with 22 establishments in the area along 14th and H Streets, giving new meaning to “the Strip.”

In 1983, the Franklin Square Association was created and began working with DC officials to clean up the neighborhood. By 1989 they had closed 19 of the 22 sexually oriented businesses.

By 2002, when Leon Zeiger died, the Casino Royal had been demolished. Office buildings replaced what he had claimed to be “the leading club between the Copacabana in New York and the Fountainbleu in Miami.”

Today, activity along what was the Strip is that of people walking to work, not to see Mae West. Few realize what the block was. But for a time, as Zeiger once put it, “We made Broadway out of 14th Street.”