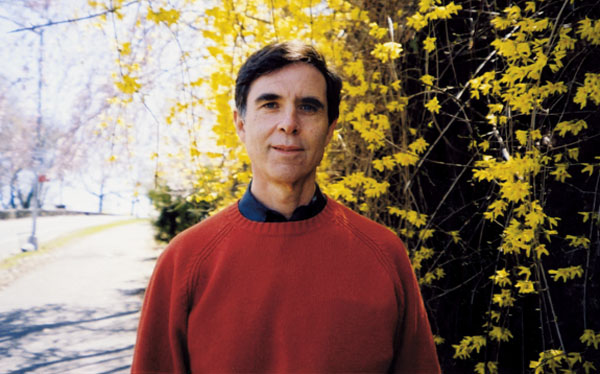

Ken Gorelick is a psychiatrist who believes in the therapeutic power of literature. He sometimes asks patients to read poetry and to write their own. In doing so, he says, people “find the truth of their own experience reflected back in a way they can recognize.”

Gorelick has also used literature in his teaching at George Washington University medical school. He asked students on psychiatric rotation to read a Raymond Carver story, “A Small, Good Thing,” because it deals with feelings of helplessness, an emotion that both doctors and patients experience—and that doctors often handle badly.

Gorelick knows how it feels on both sides of the examination table. Two years ago, at age 65, he was diagnosed with a brain tumor that turned out to be malignant. As his symptoms increased, the balance of his life changed: He became a patient more than a doctor. But he also realized that the experience offered a chance to teach new lessons to medical students—how to humanely acknowledge the impact of a bad diagnosis and how to connect with patients they couldn’t cure.

Gorelick grew up in Paterson, New Jersey. He graduated from Rutgers, then Harvard Medical School, where he also did his psychiatric residency. He joined the US Public Health Service in 1971 and was assigned to train psychiatric residents at St. Elizabeths Hospital in DC.

At the time, 4,000 patients were living at St. E’s, and there was an effort, Gorelick says, to create as normal and enriching an environment as possible. One of his mentors there knew he loved literature and introduced him to the idea of poetry as therapy.

After surgery to remove part of his brain tumor in 2007, Gorelick wrote in a poem:

Looking back I feel my life has been right.

No second-guessing that this or that might

have been better,

No ache that I might have climbed higher

mountains.

I am in a generous leisurely mood with

myself,

Filled with gratitude and awe for what

has been,

The gifts, the luck, the love.

Gorelick and I met twice at his house near DC’s Dupont Circle, where he lives with his wife, Cheryl Opacinch, a retired Department of Defense international-policy expert.

The first time, he greeted me warmly but had a hard time expressing himself. He realized something was wrong but hoped his mind would clear if we kept talking. When it didn’t, I asked his wife to join us. She recognized that he was having a seizure; it had happened before and is a symptom of brain tumors. There were no physical signs—no tremors or loss of consciousness—but he needed medical attention.

He went to George Washington University Medical Center and was treated with steroids to ease swelling in his brain. A week later, he was back home and called to resume the interview.

Why did you study medicine?

I came from Jewish-immigrant roots. My father worked in a shoe factory, but it was his dream for me to study medicine. When I was four years old, he had a heart attack and the doctor came to the house every day. I was very impressed by what he did for my father.

Why psychiatry?

I was fascinated by the idea that Freud had developed a way to understand the invisible parts of life. What an amazing miracle—to understand life stories.

You talk to students about your experience of being a patient. What was your first inkling that something was wrong?

In 2007, I realized I was having problems with my memory. It was simple things—I would go to urinate and discover later that I had forgotten to zip up. It was happening too often. I decided to go for an MRI, thinking there was a possibility my brain would come back looking like Swiss cheese. I was worried about early-onset Alzheimer’s disease or blood-pressure-related dementia. Even if there was nothing that could be done, I needed to know.

The morning after the MRI, my phone rang. My internist said, “Ken, where are you? What are you doing?” I told him I was driving to the dentist. He said, “Forget the dentist—this is a lot more important. It looks like you might have cancer. Can you come right down?”

This was over the phone?

Yes. It put me into panic mode. My first thought was that the dentist charges for missed appointments. Then I started thinking: Am I going to tell my friends, my patients? I decided to be as transparent as I could be. I called Cheryl right away.

How did she react?

She was dismayed but immediately turned positive: “We’re going to beat this.”

How did you select a doctor?

I went to see Arthur Kobrine, the doctor who had treated former White House press secretary James Brady after his brain injury during the assassination attempt on President Reagan. Dr. Kobrine said that the films showed a mass in my brain, that it was not necessarily cancer and didn’t demand action except to keep an eye on it. It was a big relief. He suggested we repeat the MRI in four weeks and again in seven weeks.

Cheryl felt it was important to get another opinion. I spoke to doctors at Johns Hopkins, who concurred with the “wait and watch” approach. I also went up to Harvard. First a neurosurgeon examined me. Then the tumor board at Harvard met about my case and decided we needed a tissue sample to confirm a diagnosis, but not a lot would happen after that. If they discovered it was cancer, they couldn’t offer any cure.

What did you decide to do?

We were about to leave for the Chautauqua Institution in New York for the summer. The doctors weren’t telling me anything I could grab onto. So we went at the beginning of June, and it was a terrific summer. I was feeling very well. But I noticed that I had a tingling sensation in my left hand. By August, I started getting headaches when I lay down to go to sleep.

What were you thinking?

That I could still function. I was still enjoying myself. I didn’t think there was any cure I was missing out on. But I realized I needed to have another MRI sooner than expected.

I managed to get an appointment at Johns Hopkins with Dr. Henry Brem. I liked him instantly—he was very caring. He showed me the latest MRI. It had cancer lesions all over it. I asked if he could remove all of the malignancy—remove half of my brain if necessary. He said unfortunately not. But he did want to do some surgery to remove part of the tumor.

What was it you liked about Dr. Brem?

He knew how upsetting this diagnosis was, and he said, “I’m very sorry.” It is such a simple thing, but oddly enough very few doctors say that. They express medical knowledge and professional concern. But it’s not the same thing.

Did you have your surgery at Hopkins?

No. After I saw Dr. Brem, I was told he was not going to be available for at least three weeks. Cheryl said, “Can’t you plead the Harvard connection?” That moved it up to two weeks. As it turned out, my sister in New York wanted me to get another opinion. I went to see a brain surgeon at New York University Medical Center and had a partial seizure en route to his office. I had my surgery there because it could be scheduled immediately.

After surgery, what were your options?

I knew the prognosis was terrible. I asked the surgeon at NYU if there were any experimental treatments under way, and he said no. He was a surgeon—oncology wasn’t his field. I’ve since learned that there were brain-vaccine studies just beginning at UCLA and UCSF.

Then I went back to Johns Hopkins and saw an oncologist. His message was basically the same: “There is no cure. Don’t do anything that will mess up your quality of life.” He could only offer me the standard chemotherapy treatment. I had the standard treatment, and I had the standard response—continued growth of the tumor.

I began to look into programs at all of the major cancer centers. When my symptoms returned in July 2008, I decided to go to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center at UCLA, one of only four centers doing vaccine trials on recurrent brain tumors.

Why do you think the doctors you saw were so unwilling to consider other options?

As a physician, if you can’t offer something curative, you have a feeling of helplessness. That is difficult to handle. Nobody likes to feel helpless. Under these circumstances, doctors want to feel they’ve offered you all that they can, and then they want to get out.

Is that why you ask your students to read “A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver?

Carver writes about helplessness. The story is about a couple whose child is hit by a car and dies in the hospital. Before the boy was hurt, his mother had ordered a birthday cake. The baker keeps calling about a birthday cake that they never picked up. The parents get so angry that they go to the shop to confront the baker about the harassing calls. When they tell him why they didn’t pick up the cake, the baker stands there in limbo. He tells them how sorry he is about their son. He really listens, and he empathizes with their grief. Then he opens up the oven and takes out cinnamon rolls and convinces them to sit down in the shop for hot rolls and coffee.

The couple and the baker have a real exchange. It becomes a way to transcend anger. Doctors hate feeling helpless. But it doesn’t matter that the baker doesn’t have all of the answers. He offers what he can—empathy.

How are you doing now?

My MRIs are showing more cancer and more swelling of the brain. I’ve been on a chemotherapy regimen directed by Dr. Ingo Mellinghoff at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Through Mellinghoff, I was also able to get into an experimental trial of a new type of drug at a research institute in Nashville.

I am feeling fatigued. I don’t want to feel like I’ve been cheated by life. It’s my job to have the best possible life. There are some patients who have lived a long time with this, and I hope I’m one of them.

Why are you still teaching medical students?

I want them to know that they should acknowledge patients with serious illness. It is not an admission of fault or hopelessness. I want them to make the human connection. Teaching is a way for me to make that connection and, perhaps, to make a small piece of myself immortal.

This article first appeared in the May 2009 issue of The Washingtonian. For more articles from that issue, click here.