Pete Ashooh is about as old school as an FBI agent gets. From the buzz cut to the thin smile to the sensible black shoes, he’s the archetypal gumshoe—Dragnet’s Jack Webb. With one difference: Ashooh is of Lebanese descent.

He drives the streets of the capital in a silver Dodge. The trunk usually holds an MP-5 submachine gun and a few bulletproof vests. “I keep my baby Glock in my gear bag,” he says one day as we cruise across the Potomac River.

In early 2002, Ashooh was summoned to a meeting at the US Attorney’s office in Alexandria. The interview room had bare walls, no windows, a conference table. Seated there was a young man who also traces his origins to the Middle East. He was wearing an orange prison jumpsuit, serving time on an embezzlement rap.

For his protection, we’ll call him Youssef.

The inmate had asked to meet with Ashooh. A prisonmate was one of the men who had helped the 9/11 hijackers get fake driver’s licenses. Ashooh had investigated them as accessories to the hijackings and gathered evidence to jail them. His affidavits on the case became part of the 9/11 Commission report.

Now Youssef told Ashooh he remembered seeing his prisonmate at a mosque in Arlington. He had seen him again at a Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles office. He suspected that the DMV agent had helped the man get licenses. Could his tips be useful?

Ashooh and Youssef talked for an hour and a half. Both had grown up in Northern Virginia. They chatted about Middle Eastern dishes at their favorite restaurants. They talked about high schools and people they might both know.

“We hit it off,” Ashooh says.

Youssef said he was racked with guilt about the embezzlement scheme that had landed him in prison. A youthful mistake, he called it.

“When I get out, I want to work with you,” he told Ashooh. “I want to make up for what I did.”

Ashooh took notes. At the end of the interview, he placed them in a manila folder and shook hands with the inmate.

“I’ll call you,” Youssef told him.

Ashooh filed away Youssef’s name. He had heard similar offers during his 25 years with the FBI.

The FBI has always relied on informants to make cases, but they have become more important in its new mission of stopping the next terrorist attack.

For decades, the FBI has made its reputation investigating clear-cut crimes—kidnappings, espionage, bank robberies, white-collar fraud, drugs, organized crime. Agents are often able to finish a case and clearly state what the crime is, what the damage was, and prove that something bad happened. Now, more than eight years after the 9/11 attacks reoriented the agency toward national security and counterterrorism, many of its cases are murkier.

Most of the FBI’s arrests in terrorism cases now come long before the attack itself, meaning the ultimate intent of the plot or the suspect isn’t always clear—and it’s not even always clear that a crime has occurred.

“The FBI has changed its policy—it’s trying to intervene much earlier,” says Gary LaFree, director of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, based at the University of Maryland. “That creates a paradox. The public wants law enforcement to get involved earlier, but the farther you get up the threat chain, the less crime there may be to report and the less convincing it might be to a jury.”

This fall, in what US attorney general Eric Holder said is perhaps the most dangerous plot uncovered since 9/11, agents working in New York and Denver arrested an airport-shuttle driver, Najibullah Zazi, for conspiracy to use weapons of mass destruction (explosive bombs) against persons or property in the United States. We may never know what his ultimate target was.

In many cases, the line between aggressive talk and terrorist plots constantly worries agents on the front lines of the threat.

“In terrorism cases,” LaFree adds, “the majority of suspects are convicted of other offenses, like firearms trafficking or money laundering. The charges are much less serious.”

Someone convicted of plotting a terrorist attack might get life in prison; a person who might be a terrorist but has been convicted only of selling guns could get a year or more.

Those parameters make cases hard for the FBI—and harder still to explain to the public.

LaFree asks: “What would have happened if the 9/11 hijackers had been arrested before the attacks? They had committed immigration violations and were carrying fake licenses. They hadn’t done that much, and they might not have done much time.”

The arrest of Mohamed Atta in 1999 or 2000 might not have merited much notice in the press, and certainly his name would be lost to the public consciousness by now.

Which raises a dilemma.

“When do you make the arrests?” LaFree asks. “If you make early arrests, you might have thin charges; if you wait too long, the plot can be hatched.”

This tension has played out hundreds of times across the country since September 11. How do you know if you’re investigating a full-blown terrorist or just a shady underworld character? How do you know how far to push an investigation? How do you talk about that case once it goes public with indictments, arrests, and prosecutions?

Agents across the national-security spectrum know that the ground rules have changed and that their margin of error is thin.

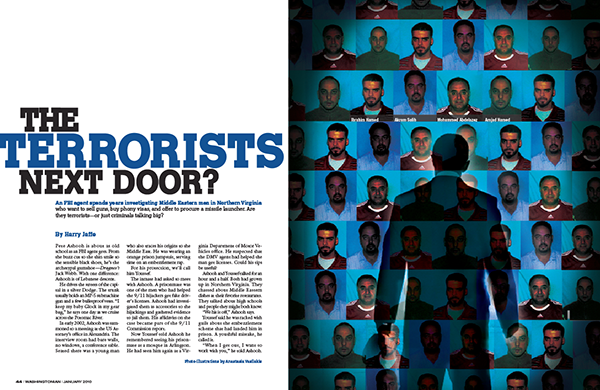

For Pete Ashooh, this national debate and discussion played out locally in an investigation of a group of men from Jordan, Egypt, and Palestine who were involved in criminal activities: bribery, extortion, drug use. Yet some were also selling guns, trying to get counterfeit passports, and promising to supply missiles capable of hitting the Pentagon.

Was Ashooh tracking common criminals? Terrorists next door? Operatives with connections to Hezbollah and Hamas? Did they really have access to the promised missiles? Should we have waited to find out?

Besides being a quintessential FBI agent, Ashooh is an ideal investigator of would-be terrorists from the Middle East. One of the few agents who can trace his roots to the Levant, Ashooh is second-generation American. His grandfather came to the United States in 1910 and served in World War I. Ashooh doesn’t speak much Arabic, though he has a natural kinship with Middle Easterners.

His kinship with the feds goes back to his father, Joseph, who worked for the FBI and retired as an agent in the Washington Field Office. Ashooh grew up in the Franconia area of Northern Virginia with a dad who came home from work with a revolver strapped to his leg.

Ashooh has an older brother and a younger sister. At Edison High, he played baseball, soccer, and tennis. He did well enough academically to graduate from the College of William & Mary.

With designs on going to law school, he took a job as an analyst at FBI headquarters on DC’s Pennsylvania Avenue. One of his first assignments was to help then-director William Webster gather evidence in the ABSCAM investigation of congressmen charged with taking bribes. He interviewed witnesses and wrote reports. “I got the bug to get out and do the real thing,” he says. “I wanted my own cases.”

In 1984, Ashooh became an agent. So much for law school.

Detailed first to New Orleans, he worked the basics: drugs, gambling, bank robberies. He tracked down a pilot who had been flying drugs into New Orleans from Tampa. FBI agents met the pilot and arrested him on the tarmac. The pilot looked at Ashooh. “I know you,” he said. They had been in the same karate school. The pilot became one of Ashooh’s first undercover sources. Wired with a recording device, he helped Ashooh bring down a big narcotics network.

“To me, that was what the FBI did,” Ashooh says. “Take down large criminal enterprises.”

From New Orleans, Ashooh went to the FBI’s Newark office. He worked with a team of agents to dismantle a conspiracy in which cops protected drug dealers. “You couldn’t tell the difference between the cops and the wise guys,” he says.

Ashooh had found his calling: using wiretaps and informants to infiltrate old-school organized-crime networks—“Mustache Pete” mobsters, he calls them.

In April 2000, Ashooh got a transfer to the Washington Field Office. He was home, operating from the office his dad had worked in, living with his wife and children in Northern Virginia, working cold cases.

A year and a half later, hijackers crashed passenger jets into the World Trade Towers, the Pentagon, and a field in Pennsylvania. The FBI ordered Ashooh to join the new national calling: ferreting out terrorism networks to make sure the United States wasn’t attacked again.

Ashooh didn’t warm to the task. He had spent nearly two decades working complicated, long-term investigations that usually resulted in putting thugs in jail for more traditional crimes. He discovered that investigating and proving terrorism could take him into uncertain legal terrain.

Youssef called Ashooh in 2004. “Remember me?” he asked. “I said I would call. I have been out of jail for about six months.”

Youssef was a member of a prominent family in Northern Virginia’s Middle Eastern community. He was thought to have connections to politicians and businessmen in the Middle East. After his release, friends had taken him in. Members of the Middle Eastern community in Annandale had loaned him money so he could get back on his feet.

One of his benefactors was Akram Salih, known in the community as a successful contractor. He was born in Puerto Rico but moved with his family to Palestine when he was about four years old. Ten years later, after his parents divorced, he moved to Annandale to live with his father. He attended Annandale High, worked for his father’s remodeling business, and started his own firm, Palis General Contracting. Salih remodeled many old homes on Capitol Hill.

Salih lived with his wife and three children in a tan-brick home on Hirst Drive, off Little River Turnpike.

Amjad Hamed, Salih’s younger brother, lived in the basement. Amjad had grown up in Palestine; he had come to the United States in 1978 as a permanent resident but traveled back and forth to the Middle East. He was in his early thirties. He liked to smoke, drink coffee, and talk about his connections with Fatah, the Palestinian political organization headed by the late Yasir Arafat.

Youssef started spending time with Amjad at the Salih home.

At Ashooh’s first meeting with Youssef, they made a pact. “I am getting to know the Middle Eastern community in this area,” Youssef told him. “Some of my old friends have become radicalized. I want to be your listening post.”

He added, “The younger brother of one of my friends has approached me to do a few things.”

His name was Amjad Hamed.

Youssef and Ashooh would check in with each other about once a month. In the spring of 2006, Youssef left a message: “I think I have something.”

Amjad Hamed had asked Youssef if he could get counterfeit US visas for six of his “associates” who wanted to emigrate from Jordan and the West Bank. He explained that his friends were in danger of being arrested by the Israelis and needed illegal entry to the United States.

Youssef and Amjad had been talking for months about politics and money. They would meet in the parking lot of Pinecrest Plaza on Little River Turnpike in Annandale, not far from Akram Salih’s house. It had a Staples, a Hollywood Video, a Quiznos. The Starbucks was always hopping. Youssef and Amjad would grab a cup, sit in their car in the parking lot, smoke cigarettes, and plot.

When Youssef told Ashooh that Amjad had asked for fake visas, the FBI agent realized it was time to wire up his source. They worked out a routine: They would meet at a pair of blue Dumpsters in an alley near the shopping center. Ashooh would fit Youssef with a device that would both record and beam the conversations to listening devices. Ashooh and other federal agents would watch the meetings and listen to the conversations.

Ashooh also started paying Youssef as if he were a government contractor.

Before Youssef could get the fake visas, Amjad would have to produce passports for the people he wanted to get into the country. For weeks there was much talk but little action. Amjad took Youssef to the basement of his brother’s house and gave him a lie-detector test.

In early April, Amjad called Youssef: “I have what we’ve been talking about.”

On the day Youssef was scheduled to pick up the passports, Ashooh met him at Pinecrest Plaza, wired him up, and gave him last-minute instructions.

Ashooh was a bit woozy. He had gotten a concussion the night before at a karate class.

Youssef waited in the parking lot. Amjad called and asked him to come to the house. He drove down the road and walked into Amjad’s basement apartment. Amjad handed over six Palestinian Authority passports.

“How did you get them?” Youssef asked.

“A passport just as this one has never left the country and was never stamped,” Amjad said. “We got everything organized, and a decision was made. When we got the okay, they sent it to us. I came and found it at the front door.”

Youssef said his source for the fake visas wanted to know if Amjad was serious about the scheme and powerful enough to pull it off.

“As far as being powerful,” Amjad said, “I can bring you the entire universe if you want. Anything you want in the area. If you want him to go to Lebanon to bomb everyone, he will go to Lebanon.”

Amjad said that procuring visas was crucial for his associates. If Youssef could produce more visas, Amjad said the fees would “make you a millionaire.”

Youssef drove back to Pinecrest Plaza. Ashooh was waiting. They met by the blue Dumpsters. Youssef handed over the passports and his wire. “I can’t believe I actually got them,” he said.

Youssef described in detail what Amjad had said. If he remembered a snippet of conversation later that night, he would call Ashooh and relate it. They had to wait weeks for FBI analysts to translate the tapes from Arabic for a complete transcript.

Why did Amjad Hamed trust Youssef and believe he could produce fraudulent visas? Ashooh has a few theories.

Youssef was well known in the Middle Eastern community. His family was thought to be well connected in the diplomatic community in the States and abroad.

He had committed a crime and done time, so he wasn’t afraid of walking on the criminal side. When he’d returned from prison, Amjad’s family had helped Youssef. He owed them.

In Amjad’s small circle, it was believed that Youssef had wasta, an Arabic word that denotes the use of powerbrokers to manipulate political situations. Youssef, they believed, had juice—he could make things happen.

Ashooh delivered the passports to the State Department’s diplomatic-security service; investigators confirmed their authenticity. The Israelis were aware of the people they identified—some had been in and out of Israeli jails.

A few weeks later, Youssef returned to Amjad’s place; Amjad handed over $2,500 in partial payment for the visas.

Ashooh could have arrested Amjad Hamed at that point. By conspiring to procure falsified visas, he had committed a federal crime—but just getting the arrest isn’t the point of these FBI national-security investigations anymore. Ashooh believed Amjad had the potential to lead him to a broader conspiracy; they needed to figure out the extent of the organization before they moved.

Amjad Hamed liked to pump up his terrorist credentials. The feds had him on tape saying he had been a member of Force 17, Fatah’s elite commando unit and later Arafat’s personal security detail. He talked often about his days in Fatah. Long before Hamas and Hezbollah adopted terrorist tactics, he said, Fatah had been using them to attack Israel. “We were the first,” he told Youssef.

Fatah, Hamas, and Hezbollah “are one,” he said: “We all work together. We all do operations together. Don’t let people fool you.”

Amjad told Youssef he admired Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah. He gave Youssef tapes of Nasrallah’s sermons.

In assembling the pieces of the investigation, Ashooh had to assess whether Amjad was a thug out for money or a terrorist capable of taking part in an attack.

“He wasn’t just making up stuff,” Ashooh says. “He could smuggle passports from the West Bank and Israel. To us, he was an intelligence officer for a terrorist group.”

A few weeks after he paid $2,500 for the visas, Amjad started hassling Youssef for the documents. By summer, he said his associates in Palestine were concerned.

“They called yesterday and the day before yesterday,” he said. “I did not answer. They pressure me: ‘We can’t wait. We need to work, we need to make money.’ ”

Ashooh had no intention of creating fake visas. He had confirmed the authenticity of the passports and lured Amjad into paying for the visas up front.

In July, Amjad summoned Youssef again. “These passports are the biggest responsibility of my whole life,” he said. “They are calling me saying one, two weeks. I want one request from you. Call your people and tell them if they can’t get the visas in two days, return the passports.”

Youssef gave the passports back in August. He said the war in Lebanon between Israel and Hezbollah had prevented his contacts from getting the visas. Beirut was under attack, and they had been forced to leave.

Amjad said he understood.

Youssef kept meeting with Amjad, but he had little to report for many months.

In early 2007, Amjad contacted Youssef about another deal. A Palestinian diplomat was trying to unload untaxed cigarettes. Could Youssef come up with $4,500?

Just to stay in the game, Ashooh wanted to buy the cigarettes. He had to go through bureaucratic hoops before the FBI would sanction the deal and supply the cash. In the time it took to get the money, Amjad found another way to unload the cigarettes.

Ashooh was disappointed. The FBI agent took his family to downtown Fredericksburg one weekend in May to attend a sports banquet for one of his sons. They were in the middle of lunch when his cell phone rang. He saw that it was Youssef. He rarely called on weekends. Ashooh excused himself, walked out to the street, and took the call.

“Amjad told me he was sorry he had to sell the cigarettes to someone else,” Youssef said. “He didn’t want to let me down. He said he wanted to make it up to me. He said he could get me guns.”

Ashooh had two thoughts: I’ll take guns over cigarettes any day, and let’s see if Amjad can actually make good on his offer.

Youssef told Amjad he was in the market for any type of weapon he could find. Money wasn’t an issue.

In the first deal, Amjad told Youssef he could get him a semiautomatic pistol for $750. On May 23, Youssef showed up with the cash at Akram Salih’s house. Two days later, Amjad rolled into Pinecrest Plaza in a small truck. Youssef got into the passenger’s side. Amjad handed over a Smith & Wesson 9-millimeter semiautomatic pistol. The serial number had been rubbed off. Amjad was wearing latex gloves to keep his prints off the gun.

“You know I am a convicted felon,” Youssef said, “and I can’t buy a weapon legally.”

Amjad said he understood. “This doesn’t have a number,” he said. “I got it for you with the numbers erased.”

Amjad gave Youssef a handwritten list of guns and prices. It said Amjad could provide an AR-15 semiautomatic rifle for $2,400 to $2,800, a fully automatic M-16 for $3,500, and a shotgun for $1,400 to $1,600. “I can get as many as ten M-16 fully automatic rifles from my supplier,” he said.

Youssef asked if Amjad had connections “to transport the weapons from one state to another or one area to another.”

“Yes,” Amjad responded. “I have connections to transport from America directly to the middle of Lebanon.”

The second deal went down a month later. As they had done more than 100 times, Ashooh met Youssef at the blue Dumpsters. He fit Youssef with a wire and gave him an envelope with cash. Minutes later, they drove separately to a parking lot behind a Kmart off Little River Turnpike, just east of Pinecrest Plaza.

Amjad arrived in a white van. Youssef reached into the window and gave him an envelope containing $2,600. Less than 15 minutes later, Amjad returned in the van. He gave Youssef an SKS sniper rifle outfitted with a scope, a bipod stand, and a laser finder. He also handed over an 8-millimeter semiautomatic handgun.

Amjad said he expected another shipment of guns the next month—plus a higher level of weaponry.

“Are you still interested?” Amjad asked.

“I want it,” Youssef said.

“A missile,” Amjad said.

“Don’t play with me,” Youssef said. “Is it true?”

“It is true.”

“What is it? Rocket? Missile?

“A missile.”

“Does it come—pay attention!—does it come with equipment to shoot it out or only the missile?”

“No, no, no,” Amjad said. “When I say missile, it is with everything—with the controls if you want to hit the Pentagon.”

“With the controls? What? You want to hit the Pentagon?”

Amjad replied: “You can put the bottle on it, the blue bottle, and hit the Pentagon.”

Later in June, Amjad contacted Youssef to discuss the M-16s and the missile launcher. Youssef said he needed two weeks to get the money.

What happened next surprised Ashooh—and deepened his suspicion that a terrorist network might be showing its hand.

Youssef contacted Amjad Hamed’s cousin Ibrahim Hamed and asked to meet him for coffee. They agreed to meet at the Starbucks in Pinecrest Plaza.

They got their coffees and sat at a table. Ibrahim said he had supplied all the guns. “Everything he gave you came from me,” he told Youssef. “I’m the one that gave him everything, the 9 and the 11. Yes, it came from me. He begged me to give him some. Do you think Amjad knows anything? Amjad is the dumbest one in Virginia.”

Amjad had no connections, Ibrahim said; Ibrahim had brought the guns in from Florida. He was angry with Amjad. He said he had an opportunity to buy 39 AK-47s but Amjad had screwed up the deal.

If he had known Youssef was shipping the guns to Hezbollah, he would have gotten him “the newest shit” that could “turn it from a handgun to a machine gun.”

Ibrahim said he was aware that Youssef was in the market for a missile. He wanted to deal directly with Youssef and cut Amjad out.

Whether Ibrahim was all bluster or for real, his conversation with Youssef was further confirmation that both Amjad and his cousin believed Youssef was connected to the Lebanese terrorist group Hezbollah.

In January 2008, Youssef met with Amjad in the Pinecrest Plaza parking lot. Amjad apologized for not coming across with the missile.

Ashooh was three years into his investigation. He had gathered evidence that seemed to indicate Amjad Hamed might be involved in terrorist activities.

Amjad had tried to buy fake visas to give Middle Eastern associates illegal entry into the United States. He had sold firearms to a man he knew was a convicted felon. He had talked about shipping weapons to Lebanon. He had said he could supply a missile that could hit the Pentagon. He had described himself as a member of Fatah.

Amjad was dealing guns from his brother’s house; his cousin Ibrahim Hamed was supplying the weapons.

Ashooh was reporting his investigative breakthroughs up through the FBI ranks. His bosses didn’t seem impressed—shady, sure; the next world-class terrorist cell, unlikely.

Ashooh figured that might have something to do with the US relationship with Fatah. When Amjad Hamed was a member of Force 17, Fatah was considered a terrorist organization. But by the time Amjad was promising to sell missiles to a confidential FBI source, Fatah was considered an ally.

What about the taped conversations about sending weapons to Lebanon? Ibrahim’s offer of the best stuff for Hezbollah?

Were the juiciest offers—for a missile—a legitimate threat or just the equivalent of barroom bluster?

Some members of Youssef’s circle in Annandale were in the automobile business. They bought and sold cars, shipped many to the Middle East.

Akram Salih, Amjad’s older brother, summoned Youssef to his house near Pinecrest Plaza on May 23, 2007. He wanted Youssef to fly to Chicago and collect a debt.

Akram said a Jordanian man owed his friend Mohammed Abdelazez $38,000. Mohammed in turn owed Akram money. If Mohammed could get his cash, he could pay Akram.

The Jordanian was scheduled to be in Chicago to attend a car auction. Akram gave Youssef the Jordanian’s itinerary, his cell-phone number, and his description. He asked Youssef to “beat up” the man to collect the money.

Youssef related the information to Ashooh.

Working with FBI agents in Chicago, Ashooh located the man Youssef was supposed to rough up. The man said he did business with Mohammed and they’d had a dispute over the shipment of two cars. The amount in question was $38,000. FBI agents told the Jordanian of the plan to collect the money by force.

Youssef then accepted the job from Akram Salih to fly to Chicago, beat up the Jordanian, and get the $38,000. In the ruse, he never actually went to Chicago.

On June 20, 2007, Ashooh gave Youssef $10,000 in cash from the FBI. Youssef arranged to meet Akram in a shopping-center parking lot on Little River Turnpike. He said the Chicago trip was a success: He had beaten the victim bloody, but the Jordanian could give him only $12,000. Youssef said he had kept $2,000 as payment, and he handed over $10,000 to Akram Salih.

Though Salih was disappointed that Youssef wasn’t able to shake the Jordanian down for $38,000, he saw it as a win. They would do something similar and “make up for it next time.”

Word that Youssef had busted up a man in Chicago and returned with $10,000 raised his profile. In April 2008, Mohammed connected him to a man named Sameh Ibrahim. He asked Youssef to get him out of a jam with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Sameh had arranged a marriage of convenience with an American woman but had botched his filings and was about to be deported. He wanted Youssef to make sure his “wife” didn’t spill the beans to the feds; he also wanted Youssef to bribe an ICE agent.

Sameh also asked Youssef to get fake driver’s licenses for his two sons. Youssef said it all could be done for $4,500. Sameh gave him a $500 down payment and promised to raise the rest.

On the night of September 29, 2008, Ashooh donned his tactical gear, body armor, and baseball cap and drove to the Kmart parking lot on Little River Turnpike. Ashooh’s FBI bosses had told him to end his investigation and take down the subjects. The plan was to arrest the seven suspects in various locations, but the main event played out behind the Kmart.

The bait was a simple buy-bust. Mohammed, the car dealer, had a green card but wanted a passport. He had agreed to pay Youssef $5,000 for the fake document. On the night of the arrests, Mohammed was supposed to pay the cash and get the passport. Akram Salih was supposed to be with him in the parking lot.

In the car with the two suspects, Youssef was supposed to signal when the deal was done; Ashooh, backed up by federal and local cops, would jump out and make the arrests.

At the same time, police and FBI agents were set up to arrest Amjad Hamed, who had moved to Springfield. Agents were ready to take Sameh Ibrahim and his sons into custody on charges of conspiring to bribe an immigration agent.

Ashooh was conflicted. He was excited about making the arrests but also believed there was potential for expanding his investigation of wrongdoing and, perhaps, terrorism. He was willing to keep dangling Youssef as bait in Annandale’s Middle Eastern community. But his FBI superiors wanted to close out the investigation.

Everything was going as planned in the Kmart lot. Youssef and the two subjects had pulled their car behind a Chevy Chase Bank. They were talking. Ashooh, parked about 30 feet away, was listening.

Youssef had several ways to signal Ashooh that the deal had gone down: He would say, “Are you happy now?” and throw his cigarette out the window. If neither of those worked, he’d flash his brake lights.

Fairfax City cops were stationed in marked cars at the exits; a chopper was ready to be dispatched to light up the lot.

A motorcycle was parked between Ashooh and Youssef’s car. As the deal was coming to a head, the cyclist approached the bike, started to put on his helmet, got a call on his cell phone, and started talking. He blocked Youssef’s car. Youssef tossed the cigarette. He pumped the brakes. Ashooh didn’t want to run over the motorcyclist.

When Mohammed and Akram opened their doors to get out, Ashooh had to move. He gunned his car to block Youssef’s, two other FBI agents hemmed it in, Fairfax police cars raced in with sirens blaring.

Ashooh ordered Youssef and the other two to kneel and said to all three: “You are under arrest.”

The arrests of Amjad and the others went off without a hitch.

Was Amjad Hamed a common criminal trying to raise cash by any means necessary, or was he part of a terrorist network capable of launching a 9/11-type attack on the United States? Was his cousin Ibrahim a gunrunner, a Hezbollah sympathizer, or both?

Was Akram Salih a hard-working contractor who made a mistake by asking Youssef to collect a debt by force? Or was he part of a dangerous network?

If Mohammed Abdelazez could bargain for a fake passport for his personal use, could he also get false papers for potential terrorists? And if Sameh Ibrahim was willing to bribe an immigration agent to keep from getting deported, would he do the same for terrorists?

Ashooh wanted prosecutors to add up Amjad Hamed’s crimes and charge him under terrorism statutes. The legal term is “material support” of terrorism. He wrote a 30-page affidavit supporting his argument.

The case was handled by the US Attorney’s Office in the Eastern District of Virginia, in Alexandria. The prosecutors read Ashooh’s affidavit; they disagreed with his assessment.

The prosecutors declined multiple requests for interviews or comment about the case. They accepted guilty pleas from all seven men arrested. In exchange, none would serve much time behind bars. None went to trial.

The full accounting of their crimes is told here for the first time. But the question remains: Were they terrorists or thugs?

Terrorism cases aren’t easy to prove. Investigators have to gather hard evidence such as weapons or bombs. Prosecutors have the burden of indicting subjects for violating specific crimes and proving beyond a reasonable doubt that a suspect was plotting to perform a terrorist act.

Ashooh wanted to prove the terrorism angle; prosecutors didn’t think they could make the case. Should they have?

Joseph Persichini Jr. was Ashooh’s boss as head of the FBI’s Washington Field Office. He is circumspect. When Akram Salih was sentenced in February, Persichini said in a press release: “The FBI is particularly concerned about activities of those who brag about selling a missile to hit the Pentagon or casually discuss the sale of large quantities of assault rifles. These individuals, some of whom are here illegally, abused the freedoms they were afforded here.”

Persichini declines to address the Amjad Hamed case directly. I asked him about the difficulty of distinguishing between terrorism cases and other criminal cases.

“Agents get a passion for what they do, the voices they hear on tapes, the deals they witness,” he says. “They have to convey that to prosecutors and separate their personal view from the facts. The prosecutors will tell you they can indict with certain evidence; then a jury has to convict.

“It’s a balancing act between investigators and prosecutors,” he says. “But it’s an assessment prosecutors have to make.”

Prosecutors were content to have Amjad Hamed plead guilty to conspiracy to transport illegal firearms and conspiracy to commit visa fraud. In return, Amjad cooperated with prosecutors and they accepted a sentence of 18 months in prison.

On January 30, 2009, Amjad Hamed appeared before Judge Gerald Lee in federal court in Alexandria.

“Does the government want to be heard on sentencing?” Lee asked assistant US Attorney Jeanine Linehan.

“No, your honor,” she said.

Linehan had already negotiated the guilty plea with Amjad’s lawyer, Ashraf Nubani.

In court, Nubani accused the FBI source of “entrapping” Amjad. After Amjad’s arrest, Nubani said, “he’s fully cooperated with the government, has sat down with them in attempts to answer their questions, and I commend the government for looking into that matter and coming to the conclusion they did.”

Nubani pointed out that Amjad’s parents were in court, that he had been working with his brother, that he had gotten married and had a child.

Judge Lee asked Amjad if he wanted to speak.

“Judge,” he said, “I take full responsibility for my action. I am sorry for what I have done. Thank you.”

Lee said he was “nervous about the fact that there are guns involved here and what that means and what was going to be done with those guns, because I don’t think anybody was going hunting for target practice.”

He added: “You have been leading a very productive life thus far, and your letter to me suggests that you are really enjoying working and raising your family and that this is not the way you intend to live your life, by breaking the law, and you have no prior record.”

Lee gave Amjad the 18 months that had been agreed to. It was at the low end of the sentencing guidelines.

Amjad’s cousin Ibrahim pleaded guilty to conspiracy to transport one illegal firearm. He was sentenced to ten months.

Sameh Ibrahim pleaded guilty to conspiracy to bribe a federal agent and to immigration fraud for his fake marriage. He was sentenced to ten months. One son, Ayman, admitted aiding and abetting his father’s fake marriage and was sentenced to four months; another son, Basem, got five months. Both are illegal aliens.

Mohammed Abdelazez pleaded guilty to conspiracy to bribe a federal agent; he got probation.

Akram Salih, Amjad’s older brother, pleaded guilty to paying an FBI source to beat up a car dealer to collect a debt. He was sentenced to 12 months and a day.

Akram Salih was the most surprised and angry when Ashooh arrested him that September night, according to the FBI agent. The only one arrested who was American by birth, he had gone to public schools, built a business, and raised a family. He had spent 20 years making a reputation as a contractor. He says he had never considered cutting a corner, let alone breaking the law. Suddenly he was facing extortion charges.

Once the shock wore off, Akram started to sort out his emotions. There was shame, regret, disappointment, and a boiling sense of betrayal. A friend of two decades had turned out to be spying on him for the FBI.

“For 20 years, I was fine,” Akram says. We met in the office of his lawyer, Christopher Leibig. Akram had just finished serving a year in jail. “I took him into my home. I fed him steak. I trusted the guy.

“My brother had nothing to do with terrorism. If my brother had known anything about US law, he would not have gone that far.”

And all his brother’s talk about contacts in the Middle East?

“All BS.”

The missile that could hit the Pentagon?

“My brother knows nothing about missiles. Blue bottle? What’s a blue bottle?”

What about his sending Youssef to Chicago to collect a debt by force?

“It was his idea to start with,” Akram says. “He was trying to set me up. We were high-school buddies, it was schoolyard talk. I made a mistake—and I paid.”

Akram Salih says he had no idea his brother was trying to get fake visas and selling weapons to Youssef.

When he found out the full scope of the investigation, he says, he asked his brother, “What the hell were you doing?”

His brother will be deported. Of his high-school buddy, Youssef, Salih says: “How can he sleep at night?”

At this writing, all but Amjad have served their time. Except for Akram, each of those arrested faces deportation. Mohammed Abdelazez is still in the car trade. Akram Salih is trying to rebuild his remodeling business.

Ashooh has mixed feelings.

“People need to know what this case is about,” he says. He still believes it was a terrorism case. “We were investigating terrorism—whether we proved it or not.”