>> This article first appeared in the September 2010 edition of The Washingtonian. To hear first-hand from other notable Washingtonians, click here.

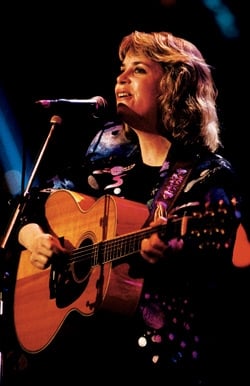

For nearly 30 years, Mary Chapin Carpenter called Washington home. She lived in Chevy Chase, Alexandria, Georgetown, and Takoma Park. “Every time was just a different time in my life,” she says, “and every place was home for a while.”

Although the five-time Grammy Award winner now lives on an 82-acre farm near Charlottesville, her father and one of her sisters still live in Washington, making it “home to me, too—it’s always like I was just there.”

Carpenter, 52, was born in Princeton and moved to Tokyo in 1969 when her father, Chapin Carpenter, a Life executive, was sent to the Asia bureau. The family relocated to Washington when she was 15, and she returned here after graduating from Brown in 1981.

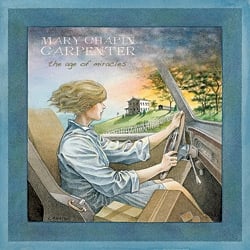

In the mid-1980s, after becoming a fixture on the local music scene, she signed with Columbia Records. Her first few albums yielded modest country hits, but in 1990 she scored a smash—and her first Grammy—with the Cajun-flavored “Down at the Twist and Shout.” With her fourth CD, 1992’s Come On Come On—whose hits included “I Feel Lucky” and “He Thinks He’ll Keep Her”—Carpenter became a star. In April, Carpenter released The Age of Miracles.

These days, Carpenter is finding touring miraculous. In 2007, she was diagnosed with a pulmonary embolism, a condition that was life-threatening—and life-changing. Forced to cancel her tour, she wondered if she’d ever write another album. Of her current tour, which ended August 19 at Wolf Trap, she says: “It’s been very celebratory.”

At home during a break from her travels, she talked about what she’s learned.

You immortalized Bethesda’s old Twist & Shout club in a song. But what’s the first one you think of when you remember Washington clubs?

Oh, gosh—of course there’s Food for Thought. It was this fabulous vegetarian restaurant in Dupont Circle that was known for its chili. Every kind of person of any color, any stripe, any orientation would go there, and it was pass the hat for the music.

When I was in my late twenties, my friend Jeff Deitchman had a longstanding night there, and my friend Reuben Musgrave and I went down to see him. Then Reuben got a gig there and let me sing a song on his set, and he introduced me to Bobby Ferrando, the owner. [Ferrando’s son, Dante, owns the Black Cat.] It was all word of mouth—friends helping friends.

So I got this gig on Friday nights from 6 until midnight. I’d play in half-hour sets and pass the hat—actually, it was a basket. I’d recognize people, and I wouldn’t pass them the basket because I didn’t want them to feel like they had to give again.

I lived in a group house in DC. My rent was probably $400, and I used to make the rent in an evening there. Well, maybe two evenings. People were extraordinarily generous. They really listened, and they made you feel welcome.

Food for Thought was a real important place for me. It helped me pay my rent and justify what I was doing, and I made a lot of friends.

What came before Food for Thought?

My first open-mike night was at the Red Fox Inn in Bethesda. I took off a year between high school and college, and I worked the cash register at Brentano’s in Chevy Chase and as a waitress at the Foundry in Georgetown. I wasn’t old enough to be a cocktail waitress, so I worked the oyster bar and cut my hands up. Anyway, I became best friends with a girl who also worked at Brentano’s, and she dragged me to the Red Fox Inn.

But I only played there once because then I discovered Nanny O’Briens in Cleveland Park. In those days, it was called Gallagher’s Pub. I think I made more friends there than anywhere else, and Sunday nights became a real gathering place. You’d listen to your friends and wait your turn.

In the beginning I was so nervous, I couldn’t even say anything—I’d just play. And then after a while I sort of timidly asked the host if I could audition for a job. He said, “Well, the owner’s right there.” And Jenny Gallagher said, “All right, I’ll hire you.”

I played Tuesday and Thursday nights in the summer and got $40 per night, and it was the greatest gig I ever had. I got asked to host the open-mike night eventually, and that was so much fun.

What made it so great?

You were background music, but you’d throw in an original here and there and nobody would notice, went the joke—and they didn’t. So you’d be working on being a better guitar player or trying out something you’d just learned.

I had a day job being an administrative assistant at a foundation in Dupont Circle, and I had this great job on the side—hosting an open mike and getting paid to hang out with all of my friends. It was like being the camp counselor. It was all about fellowship and community. It sounds corny, but it really was the place where everybody knew your name.

It’s something I miss—something that is so precious. When you play festivals, that’s a version of what I’m talking about—you get to visit with old friends. But usually when you’re out on the road, you’re traveling at night in your own pod. You become really close with the people you’re traveling with, but you don’t really meet anyone new. There’s a reason people get lonely and homesick on the road.

You make playing music in Washington in your twenties sound like so much fun. Did you ever want to give up?

All the time. One night I was playing at a bar in Glover Park. It was called Ireland 32, after the 32 counties of Ireland. In those days, I’d park my car and haul my sound system and play for maybe three people a night, and it was just hard work. But that bar had a sound system, so I hadn’t unloaded mine—I left it in my car. And someone stole it and smashed up my car, and I was thinking: How am I ever going to afford to replace this?

You question your sanity when night after night you’re playing for one person.

What kept you going?

You have to be happy doing it, and for the most part I was. I have moments of doubt even now. Wherever you are in life, you have those moments. It’s a constant process of reevaluation—the dark nights of the soul. You question everything in your life. That’s what my current album is about.

Was the questioning part of recovering from the pulmonary embolism?

Yes. The physical things I had to do were pretty straightforward, but I think recovery is far more emotional and spiritual.

The embolism happened right before a tour, and it sort of torpedoed everything. I’d never been at home for such a long time. I looked at my life, and there’s not a whole lot I threw out. But it made me grateful for what I have—not that I wasn’t grateful before, but newly grateful. It brought things into sharper focus. Anytime there’s a health scare or a life-altering change, unless you’re made of stone it’s going to change you. I think I’m still processing it.

You suddenly had a lot of unplanned time on your hands. What did you do with it?

I taught myself to cook. Before, I was a serviceable cook who could read a recipe, but I really became enamored with cooking. I’d find myself watching the Food Network. Now I love to cook and have dinner parties.

After six months, I started writing songs again. I think what we do is tied up very closely with how we feel about ourselves, and I didn’t know if I’d ever write songs again. But six months later, there I was. It was an act of faith.

What do you take with you out on the road?

I take my pillow and one of my pillowcases. It just feels like home, and it smells like it. I like the idea of something familiar underneath my head.

I take a lot of books. I’m never going to be one of these people who take a Kindle or whatever—when I finish a book, I want to put it on my shelf. And I haven’t been on tour for a few years, so this is new: I can go hurtling up the highways with high-speed Internet.

It’s crazy—I don’t have high-speed Internet here at the farm. Yesterday I was reading in the New York Times about wi-fi at 35,000 feet, and I updated my Facecrap [Facebook] page to say, ‘Yes, folks, but I still can’t get it at my house.’ People say they’re going to send me a file and I’m like, no, please—it will tie up my Internet for days. But on the bus I can stay up and watch YouTube without it constantly buffering.

I read that you write songs only in pencil. Is that still true?

I do only use pencil. To me it’s ritualistic: a yellow legal pad and a pencil with an eraser. I have friends who use pen who are either far more courageous or far more sure of themselves. And I’ll edit myself endlessly.

How do you know a song is done?

Not to be a smart aleck, but you know it’s done when you’ve gotten to the end—when you feel it’s done. I’ve coined the “overnight test” now. A night seems to be enough time to look at it the next morning with fresh eyes and say, “Ugh, not this.” But when it’s a keeper, it’s fairly obvious.

When I was writing songs for the new album, I started thinking about how it all comes about—when I’m in that work mode. I work during the day. I live a half hour from town, so if I’m going to engage with civilization I’ll go to town, go to the gym, go to the market and get groceries. And then I’ll come home and work. My favorite thing is to get in bed early with a book that takes me very far away from the songwriting I’m doing.

You wrote a song and then a children’s book inspired by Eudora Welty, and your new CD has a song called “Mrs. Hemingway”—is that all drawn from your nighttime reading?

Yes. Last summer they released a new edition of Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast. I loved the book in college, but I hadn’t read it since. This version was edited by Hemingway’s second wife’s grandson, and I wondered if it would be more favorable to Pauline, his second wife. The reason his marriage to his first wife, Hadley, broke up is because he fell in love with her best friend, Pauline. I was fascinated by Hadley and what happened to her after he fell in love with her friend. I found myself looking for books about her—tracking down these out-of-print books and devouring them.

It was all very romantic and charming when they were first married and living in Paris, and I wanted to write about that stretch of time. Every day I loved what I was doing. I worked on that song for weeks. That was a song that when I was finished, I knew it was done.

“Mrs. Hemingway” isn’t exactly your standard American Idol fare, is it?

No! It’s never going to appear on American Idol. But I am absolutely into that show. I didn’t watch it much this year, but in the past I’ve gotten kind of sucked in and can’t get out. Last year I’d watch Adam Lambert—I think he’s extraordinarily talented. And it was like, “Let’s see him kill it this week.” But the show is like driving past an accident—you can’t take your eyes off it. I think Americans take a certain pleasure in watching someone cut off at the knees week after week—it’s like the modern-day gladiators or something.

How do you handle celebrity?

Fame and celebrity are bizarre. I’ve always had an uncomfortable relationship with both of them. They can be frightening sometimes, and I wouldn’t wish them on anyone. But to play your music, to follow your passion, that people want to connect with what you do—that’s the upside. It’s a gift, and it’s humbling.

What current artists do you like?

I love Josh Ritter. He writes the most intensive, lyrically beautiful, evocative songs.

The Avett Brothers. Brandi Carlile—I adore her. Anything Neil Finn does.

There is a songwriter named Gregory Alan Isakov. He has an album called This Empty Northern Hemisphere. I discovered him on satellite radio, which I have in my car because you can’t get any radio around here.

I love the band Hem. I don’t even know how to describe them—singer/songwriter, orchestral, pop. They will just transport you.

What songs do you never get tired of listening to?

I really hope you don’t mean of my own—I would never say one of mine.

Anything by Jimmy Webb. He’s a hero of mine, and I got to meet him last year. “Galveston,” “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” “If These Walls Could Speak”—oh, my God, he’s so beautiful singing his own music, not to take anything away from Glen Campbell. I listen to Jimmy Webb and I just sob.

The Wailin’ Jennys, “Heaven When We’re Home.”

An Irish band called Lúnasa opened for me years ago. They’re instrumental, and they have a song called “Stolen Apples”—I could hear that until the day I die. I usually spend that part of my show getting ready, but I’d get ready early just so I could listen to them perform every night.

What have you learned about life?

That to love and to be loved is the greatest thing in the world. It’s the thing from which everything else springs. It’s healing. It builds character and resilience. It’s everything for me.