A newly declassified issue of a technical journal published by the National Security Agency opens a fascinating window into how the United States first started to grapple with the complexities, the risks, and the potential advantages of cyber warfare.

The journal was published in the spring of 1997, shortly after the NSA was delegated by the Defense Secretary to develop new computer network attack techniques, defined then as “operations to disrupt, deny, degrate, or destroy information resident in computers or computer networks, or the computers and networks themselves.” This was “information warfare ” as practitioners then called it. And NSA’s earliest cyber warriors saw themselves on the cusp of a momentous undertaking, one for which even the agency’s own technology savvy workforce was not completely prepared.

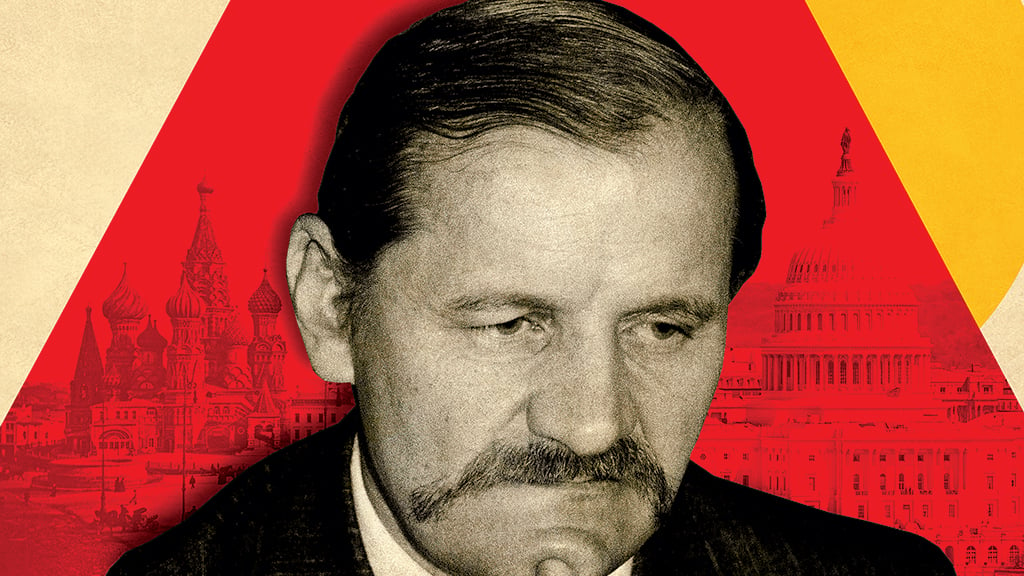

“We are on the edge of a new age, called the ‘Information Age,'” writes Bill Black, then the NSA Director’s special assistant for information warfare. It was “engulfing almost every aspect of society, including the very nature of our business”–spying on other governments’ and intercepting electronic communications.

This didn’t exactly catch the NSA by surprise; it was, and still is, the home to some of the most brilliant computer scientists the world has ever known. But perhaps because the agency understood so well the potential of technology, it knew better than most how computer networks and the increasingly integrated digital world could be exploited for strategic advantage, both by the United States and its adversaries.

In one especially prescient article in the journal, the author (his or her name has been redacted) writes about the potential of computer network attacks for “destroying enemy power facilities.”

“In previous conflicts, if you wished to destroy or disable an economic/industrial target, you needed to place ordnance on it.” But information warfare was “making possible infinitely scalable, infinitely accurate strikes on infrastructure targets by means of cyber-attacks on the information infrastructure needed to operate it.”

This wasn’t theoretical speculation. According to former military intelligence officers I spoke to when researching my book, by the late 1990s the Army was practicing for information warfare in military operations, and researchers were actively looking, as one former officer put it, “for ways to knock out the lights in Tehran,” meaning a cyber attack on electrical power facilites in Iran.

Today, a cyber attack on a US power facility is the nightmare scenario many officials use to highlight the urgency of raising America’s cyber defenses. “We know that cyber intruders have probed our electrical grid and that in other countries cyber attacks have plunged entire cities into darkness,” President Obama said in May 2009, when he announced that his administration would devote more attention to securing cyberspace.

The NSA journal also shows that America’s early cyber warriors were building up an arsenal of sorts. Any cyber attack must be directed at a vulnerability in a network, a piece of software, or a device. These are the back doors and security gaps that allow a cyber intruder to get into a system, preferably undetected. The NSA was tracking these vulnerabilities, and apparently hoarding them in secret.

“One unofficial survey within NSA listed some eighteen separate organizations who were collecting vulnerability information in one form or another!” writes one anonymous author, who seems exasperated at the lack of a more unified, coherent approach to keeping track of this valuable information. “Intelligence operatives wish to protect their sources and methods” for collecting, the author writes. “No one really knows how much knowledge exists in each sector.” And without that knowledge, there could be no “large-scale national” approach to cyber war, which, the journal makes clear, is not only something NSA wanted, but was directed to do by the Pentagon.

The journal also shows the extent to which the NSA feared that US networks were vulnerable to the very kinds of attacks the agency was imagining. Yet then, as now, there was insufficient understanding of just how much risk private networks faced, because makers and users of technology were reluctant to disclose their own vulnerabilities.

“Companies wish to maintain consumer confidence and their competitive advantage,” one author writes. The NSA’s efforts weren’t helped by poor public relations. “The public sees the government as the bad guy,” writes Bill Black, who later became the NSA’s deputy director. “Specifically, the focus is on the potential abuse of the Government’s applications of this new information technology that will result inan invasion of personal privacy.” This was hardly news even in 1997. And though it’s still true today, there is perhaps greater concern by companies and technology manufacturers that they will be held legally liable when their vulnerable products enable a cyber attack or an intrusion.

The whole journal makes for fascinating reading. It’s infused with both respect for and anxiety about the power of technology, and its rapid, unyielding proliferation in the world. The opportunities and the threats of a global network are presented as complex, risky, and yet impossible to ignore. In this respect, it is striking how little has changed.