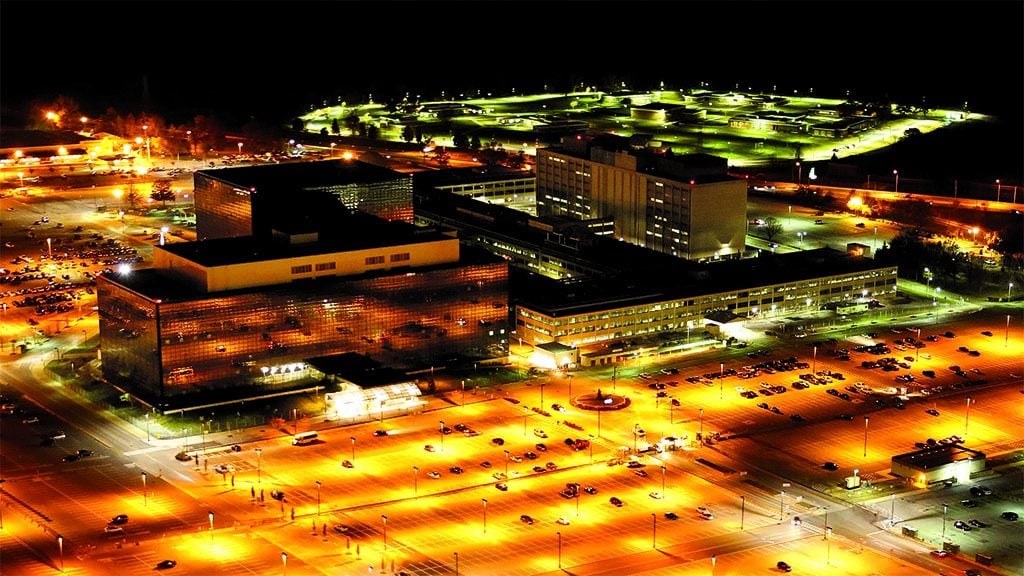

Even before Edward Snowden, the National Security Agency—the super-secret electronic spy outfit at Fort Meade—had started showing signs of thaw. Locally, NSA employees were acknowledging to friends and neighbors where they worked, while increasing links to Silicon Valley opened NSA to the outside world. Then in June 2013 came Snowden’s leak of documents demonstrating the level of surveillance aimed at US citizens, and the Agency That Would Not Be Named made headlines. In the scrutiny from the press and Congress that followed, one quip had it that NSA stood for Not Secret Anymore.

At the time, Deborah Frincke, a computer scientist and cyberresearcher, was still settling in as the agency’s research director, taking charge of developing cutting-edge tools for protecting the government’s computer systems and cracking those of our enemies. Frincke had spent most of her career as a specialist in computer security, first at the University of Idaho, then at the federal Pacific Northwest National Lab in Seattle. A relative outsider at NSA and the first woman to head the research directorate, Frincke found herself uniquely disposed to explain NSA to the world, and the world to NSA. We talked to her recently for an update.

So NSA has been making news.

Once or twice!

How did the Snowden controversy affect people inside the walls?

It was certainly very hard in the early days. It was hurtful to people who work so hard to save lives and obey the Constitution, and now the country doesn’t trust them. As one whose role is outwardly leaning, I’ve tried to explain how people outside the agency could have such a misunderstanding. I think we’ve rebounded now, and I think we understand why people got an impression that they did.

Has the controversy made it harder to attract good people to the agency?

We haven’t had trouble attracting candidates. Most people have had a chance to think about the revelations and what intelligence communities mean in general. If you ask those who’ve been here 20, 30 years, many had no idea what the agency was when they interviewed. That would be true of few of our new hires. They know what they signed up for.

What about other players in the cyber-security world—in academia and the private sector? How have you tended to those crucial relationships?

I show I’m willing to have a dialogue. At [the technology conference] Black Hat, I wore a badge that said NSA—usually they very politely put DoD [Department of Defense] under my name. I changed it to NSA so everyone would know exactly who they were talking to. What’s important at this stage is that people ask questions, raise concerns.

Speaking of how you’re received, it’s no secret that women are a minority in technical fields. What’s it like working in a male-dominated environment?

NSA does pretty well with women advancing through the ranks. It’s when I go to conferences that I see how comfortable they are with a female leader. Sometimes I turn my badge around to get a sense of what it’s like to show up as a female in the crowd, as opposed to NSA’s research director. It’s different.

It’s getting better, though. Forbes recently named you a “cool” role model for high-school girls.

It’s taken me all this time to get to the point where I’m actually cool. I was a bit of a novelty in graduate school.

Did you ever feel discouraged?

I did when I started, because I was the only one who looked like me. The atmosphere was less accepting, especially when you got into cybercrime. It was acceptable to work on proving things were safe and secure. That was cleaner than the messier world of attacks and defenses, which was more militaristic and not suitable. So I remember getting a fair amount of pushback. But when you are an anomaly and you stick it out, you get a little bit of name recognition.

How did you get into computers?

My dad was a prof, and when I was in third grade, he spent his sabbatical in Crofton [Maryland], helping the Naval Academy set up a computer. He would bring us in, and we would play with the big paper tape. I loved it. When the Radio Shack [home] computers came out, he of course bought them and I of course played with them. You had to write your own games then; otherwise you were stuck, so I got into computers very early on.

Was it your father’s experience that gave you the idea to go into government work?

I would say I grew up on a service orientation. I was really into King Arthur and Tolkien—the strong protecting the weak, the duty that we have to take care of our folks. That was part of our family culture. So it was not unnatural for me to move into a discipline where the goal was to take care of other people, to defend the systems.

But why NSA? You had a long career in academia, you worked on a start-up. There are plenty of places to use your skills.

As a scientist, there are very few places where I can say I’m directly helping the country. It’s harder when you go to a tech company that’s putting out widgets. Those things are important, but it’s not satisfying.

But the private sector is making some important widgets for cybersecurity.

I take nothing away from that. I’m just wired a little differently. It’s a happier place for me to work directly in government and try to take those skills and shape those things.

In a recent article about hackers, an industry insider said, “My concern is that the bad guys are going to out-innovate us.” Is NSA still ahead?

At the moment, yes. [NSA director] Michael Rogers recently announced a reorganization called NSA21 to make sure the same is true in ten years. We want to know what we can do to be easier to work with. Many of the innovative spirits in the industry are one- and two-person companies. How do they begin to bring their great solutions to a behemoth? Which I say with love, but we are.

That’s a huge cultural change for NSA, isn’t it? To go from being the primary producer to being a consumer?

It’s a huge cultural change. It’s a healthy change. There will always be things we’ll know how to do best. The things we buy from the outside actually allow us to focus on that. The important thing will be to maintain that focus. To farm out all of our brains, that would be a problem. But to be a savvy consumer who’s also a producer, you can be more nimble that way.

Half of NSA’s job is “signals intelligence”—spying on others. The other half is defense, protecting our computers. When you lie awake at night, are you thinking about defense or offense?

I’ll probably always think more about defense because I was raised that way. It’s also in many ways a harder problem. You have to get the defense right all the time. Offense can be successful if it gets in and gets out. Defense touches every US citizen every single day.

The vulnerability is continually widening. It’s the electrical grid, the food supply. Everything has been technologized to the point that it’s a concern.

Not all of that is NSA’s concern necessarily. It may affect Silicon Valley more. The “internet of things” means we’re bringing critical cybertechnologies literally right next to us—Fitbit, GPS, all the devices embedded in my home. That’s very personal. Yet our devices are not designed secure. Every year, more and more, so much of our lives is dependent on a fragile infrastructure. We will see breaks. If US citizens want to worry about one, it’s defense they should focus on.

What can they do?

If you don’t want GPS tracking to be on, turn it off. Have your e-mail set up so you have password protection. Think through: How did I protect my bank account today? And as political consumers, we should be asking: How do we devise our next culture? We should demand safety in our devices just as we demand seat belts.

Can you give an example?

I’m a breast-cancer survivor. Should I have a recurrence, chances are it will be at a point when the technology will enable doctors to monitor how my cancer is progressing from their office. What should be designed into those sensors so I don’t have to worry that someone else will hack that information? These devices that help regulate bodily processes—how can we make sure those are hacker-proof?

What’s the balance, though? After the San Bernardino shootings, many said our phones should be locked up tight. Given the threat we’re facing, do you say, “This isn’t about protecting your Snapchats”?

I’m not going to weigh the value of someone’s photos, whether of their cat or something I might consider important. That’s precious to them. What I ask is that as a nation we have thoughtful dialogue, think through where we do want to share information.

What if we said you can never share information about a cancer patient? What if we never share information that would help catch lawbreakers? Where do we create that balance between maximizing civil liberties and maximizing the safety and security? If you don’t get them both right, then you are not safer and more secure. We have to get them both right.

This article appears in our September 2016 issue of Washingtonian.