About Restaurant Openings Around DC

A guide to the newest places to eat and drink.

A Rake’s Progress in Adams Morgan wasn’t even officially open when it got the ultimate VIP visit: Michelle and Barack Obama celebrating the former First Lady’s birthday.

Chef/owner Spike Gjerde served the Obamas a few times before at his Baltimore restaurant Woodberry Kitchen, which prides itself on a hardcore devotion to Mid-Atlantic farmers and purveyors. At his first DC spot, Gjerde put together a spread of snacks, including Virginia hams and catfish steam buns. Then, both Obamas opted for hearth-grilled steaks (medium-rare for her, medium-well for him) with West Virginia truffle butter (yes, there are truffles in West Virginia). The former President drank a vodka Gibson.

“Their last words as they went out the door was, ‘We’ll be back,'” Gjerde says.

Needless to say, we expect tables will be in high demand. Here’s what to look for at now-open Line Hotel restaurant.

An all-local, game-centric menu fueled by a wood-fired hearth

A Rake’s Progress is named after a series of English paintings from the 18th century, which depicts a man’s journey from excess to destruction. Perhaps fittingly, the project—housed in a former church—has been a work in progress for four years.

The first thing Gjerde knew would be on the menu was a simple piece of toast to start every meal. Or at least seemingly simple. The grilled slice is made in-house from locally-grown-and-milled white spelt and whole wheat, slathered in butter and West Virginia sea salt, and served on an elegant silver platter.

“I wanted bread that was representative of this approach but was also a great complement to the meal,” Gjerde says.

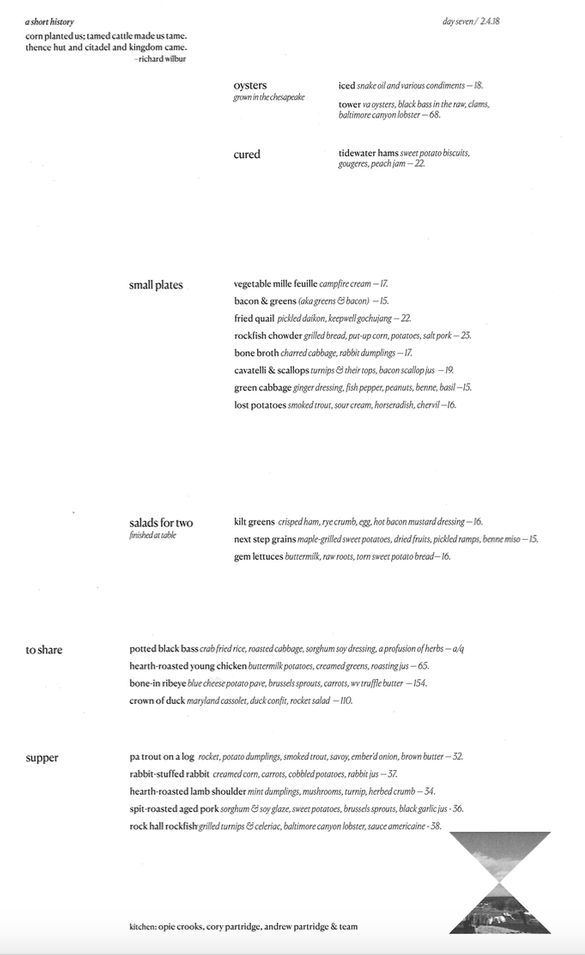

That approach is similar to Woodberry Kitchen “but with a little more polish.” A wood-fired hearth is the backbone of a game-heavy menu, but you’ll also find tableside salads for two and a “Chesapeake salt bar” supplying briny goodness from the region (oysters and Virginia hams).

Among the selection of small plates is a chawanmushi-style egg custard topped with kale, house-cured pork belly, and clarified pot liquor. The dish is inspired by a poem Gjerde read in David Shields’ Southern Provisions: The Creation and Revival of a Cuisine about the perfect pairing of bacon and greens.

“To share” dishes for two to four include a classic hearth-roasted whole chicken with buttermilk potatoes and creamed greens, as well as a larger version of the ribeye the Obamas ate. The meats are sliced at a carving station in the middle of the 132-seat dining room and served on osage orange wood platters made by a Baltimore woodworker.

Entrees (remember those?) are available for those less inclined to share. “Trout on a log” is cooked and served still-smoking on a ring of wood that’s thrown on the fire until it starts to burn. Meanwhile, “rabbit stuffed rabbit” is the Thumper version of porchetta.

Gjerde was listing local farms and heirloom varietals on his menus long before it was cool, but “pretty soon, every plate was a little novel.” Instead, Gjerde opted for a brief and poetic agricultural update for diners: “A warmer week allowed Heinz and Gabrielle to harvest kale again,” he writes on the opening menu. “Tony Conrad has let us know that the yellow perch will soon start their yearly run in the Bush River.”

The dessert menu reads even more… artistically. Rather than listing the components of each dish, it’s written with the stream-of-consciousness notes of pastry chefs Amanda Cook and Beth Bosmeny—exclamation marks, parentheticals, strikethroughs, and all. (It may be the wackiest menu we’ve ever seen.) All you really need to know, though, is that there’s a baked Alaska with buttered popcorn ice cream.

The South meets the North at the 12-seat, citrus-free bar

That’s right, you won’t find lemons and limes at A Rake’s Bar. Gjerde and co-owner/barman Corey Polyoka decided to eliminate citrus at their restaurants in 2015 as part of their intense focus on Mid-Atlantic sourcing. Instead, they now go through 900 gallons of the verjus (acidic grape juice) each year.

The cocktail menu at A Rake’s Bar is divided along the Mason Dixie line with drinks representing Northern and Southern drinking traditions. On the Southern end, you’ll find juleps and smashes using herbs from a planter built into the bar, as well as low-alcohol iced teas served in pitchers.

There’s also “bourbon & branch,” which is essentially whiskey and water—but like everything else at A Rake’s Progress, there’s a complex attention to detail behind the simplest things. The libation is based off a “branch water” tradition of adding spring water that fed a distillery back into a barrel-proof bourbon. Polyoka and his team personally collected water from the public Berkley Springs in West Virginia, which is famous for its supposed healing properties. It’s presented in mini glass pitchers (made in West Virginia, of course) alongside a pour of bourbon. “It will change the mouthfeel of the whiskey, and make it a little sweeter,” he says.

The Northern section of the menu centers around rum cocktails, shrubs, and vinegar-based “switzels.” For rum service, bartenders juice cane sorghum grown for the restaurant in Southern Maryland. That’s added to a sipping rum with little bit of verjus.

Another section of the cocktail menu dubbed “Progress” is where “we get to play outside of the pages,” Polyoka says—no historical references necessary.

You won’t find any European cordials spirits in the cocktails. Polyoka says they use a couple bottles from Chicago, but everything else is produced from South Carolina up to Maine. In fact, the bar bought barrels from a number of local distilleries so they could have input on them.

“That will be our house rail, and things we mix a lot with,” Polyoka says. “So when that barrel runs out, we’ll go pick another one from their rickhouse and that will become our new rye, rum, or brandy.”

Meanwhile, the draft list is devoted to local ciders and farm beers, meaning beers produced on farms in Maryland and Virginia.

By now you’re probably wondering: Is there anything at this place that’s not local?

Yes, in fact: wine. Polyoka says he tried an all-local approach at Baltimore sister restaurant Parts & Labor a few years ago, but it didn’t sell very well. That said, there are Virginia wines on the menu, including several by the glass. And Polyoka is quick to point out that list focuses on organic and biodynamic wineries. “They farming in the same way that we want out farmers to grow carrots here,” he says.

Plus, the wine booklets are local. If you hadn’t guessed, they’re made by a bookbinder in Baltimore.

A Rake’s Progress. 1770 Euclid St., NW.