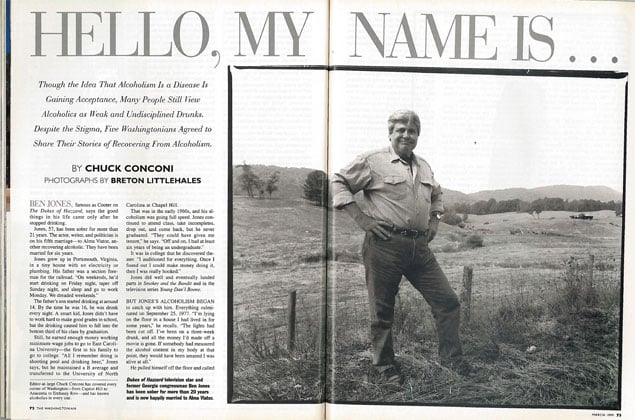

Ben Jones, famous as Cooter on The Dukes of Hazzard, says the good things in his life came only after he stopped drinking.

Jones, 57, has been sober for more than 21 years. The actor, writer, and politician is on his fifth marriage–to Alma Viator, another recovering alcoholic. They have been married for six years.

Jones grew up in Portsmouth, Virginia, in a tiny house with no electricity or plumbing. His father was a section foreman for the railroad. “On weekends, he’d start drinking on Friday night, taper off Sunday night, and sleep and go to work Monday. We dreaded weekends.”

The father’s son started drinking at around 14. By the time he was 16, he was drunk every night. A smart kid, Jones didn’t have to work hard to make good grades in school, but the drinking caused him to fall into the bottom third of his class by graduation.

Still, he earned enough money working minimum-wage jobs to go to East Carolina University–the first in his family to go to college. “All I remember doing is shooting pool and drinking beer,” Jones says, but he maintained a B average and transferred to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

That was in the early 1960s, and his alcoholism was going full speed. Jones continued to attend class, take incompletes, drop out, and come back, but he never graduated. “They could have given me tenure,” he says. “Off and on, I had at least six years of being an undergraduate.”

It was in college that he discovered theater. “I auditioned for everything. Once I found out I could make money doing it, then I was really hooked.”

Jones did well and eventually landed parts in Smokey and the Bandit and in the television series Young Dan’l Boone.

But Jones’s alcoholism began to catch up with him. Everything culminated on September 25, 1977. “I’m lying on the floor in a house I had lived in for some years,” he recalls. “The lights had been cut off. I’ve been on a three-week drunk, and all the money I’d made off a movie is gone. If somebody had measured the alcohol content in my body at that point, they would have been amazed I was alive at all.”

He pulled himself off the floor and called a friend, a recovering alcoholic, and pleaded for help. “He took me to a clubhouse in Atlanta, a recovery center,” Jones explains. “I just went cold turkey.”

Jones had tried to quit before, but this time it took. When he stopped drinking, Jones’s life changed dramatically. “A year and a half later,” he says, “I was on the number-one show on television, and 11 years later I was elected to Congress.”

The hit show was The Dukes of Hazzard, which ran from 1979 to 1985. And though Jones lost his first run for Congress in 1986, he won two years later. By 1994, Jones’s district had been redrawn and he faced the formidable Newt Gingrich. Jones lost.

Since returning to acting, he’s had a part in the movie Primary Colors and a role in Meet Joe Black. He was in an episode of the television series Sliders and April 1997’s The Dukes of Hazzard: Reunion!

He argues that alcoholism is a disease and is treatable, although he admits that the success rate is not great. “If you have the disease,” he says, “you have to deal with it one way or another. You either find abstinence or you die from it. Usually you take a lot of people down with you.”

• • •

Adam Laxalt is 20 years old, the son of Washington lobbyist Michelle Laxalt and grandson of former Senator Paul Laxalt. With his shy smile, he is very much a younger version of his highly respected grandfather. Already he has been treated for alcoholism at the Hazelden Foundation near Minneapolis.

Laxalt quit drinking January 13, 1997. He was at Hazelden trying to lie his way out of the 28-day program when the counselors confronted him with the fact that he is an alcoholic.

Laxalt began drinking heavily as a freshman at St. Stephen’s and St. Agnes School in Alexandria, where he lived with his mother. “Parents would be away for the weekend and we would have your traditional high-school party, call all the friends and everyone comes over,” he says.

“When I look back on it now, I never drank just to have a few beers and unwind. If I was going to start drinking, I wanted to get drunk. The summer going into my junior year, I partied every night.”

Though drinking dominated his social life, Laxalt, still goal-oriented, did well his junior year and the first semester of his senior year, the time most important for college acceptances.

To the concern of both his grandfather, now a lobbyist, and his mother, Laxalt chose to attend Tulane in New Orleans, a good university but one with a reputation as a party school. “I assured them I was going to be serious,” Laxalt says. “I wanted to do well in school.”

He taps his foot nervously against his coffee table and says in a quiet voice, “I got down there and it was just too much fun, too many women, and too much booze. Campus bars were open until 6 AM, and Bourbon Street was open until 6 or 7 AM.”

Laxalt convinced himself that he could handle the partying, but when grades arrived during Christmas break, he had “something in the one points.” He was determined to go back in January and “get serious.”

One night during that semester break, after drinking with friends, he broke the rule he had against driving drunk. “I was going to spend the night at my friend’s house,” he says, “but it turned out his girlfriend was staying over. It was 1:30, and I didn’t think I was so trashed.”

Laxalt seems vague about what happened next. Heading down the George Washington Parkway, he was pulled over and taken to the Alexandria police station, where he was found to have a high blood-alcohol content.

His mother was so angry she didn’t speak to him for two days. A few days later, he went to visit a friend at James Madison University and continued drinking.

On the day Laxalt was to return to Tulane, his mother took him to talk with a lawyer about his DUI arrest. “That was a tough meeting,” he says. “To have a lawyer telling me I’m up a creek. He was worried about my drinking with my level being so high. He said there was no way he could get me out of this and that I would have to undergo some kind of treatment.”

Adam and his mother cried as they rode downtown to his grandfather’s office. There they talked about alcoholism in the family and the ordeal his grandmother, a recovering alcoholic, went through when she was drinking.

“Looking at my grandfather, whom I respect more than anyone with the exception of my mother, and to see how disappointed I made them was real rough,” he says.

They told Adam his bags were packed and that he would be leaving in an hour for Hazelden.

Laxalt arrived angry and upset and told the counselor he didn’t belong there. He convinced himself that he would be out within a week. But a week later he met again with the counselor, who told him he had a drinking problem. “I broke down in tears,” he says. “I probably just sat there for 20 minutes crying.”

That moment was an epiphany. “Really, it was the best thing that’s ever happened to me in my life because at that moment I said, ‘Okay, I have a problem, and I’m going to face it and deal with it.’ Before that it was ‘I’m too young, I can’t stop now, I’ll deal with this later.’

“At that stage I wanted my life to get better. For an 18-year-old, I was as gone as you can get.”

From then on, the drinking was behind him. After finishing the Minnesota program and returning to Washington, he went to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings twice a week for the first few months but sheepishly admits he doesn’t attend them anymore. He still goes out with his old drinking buddies to Georgetown bars but says he has only water and is not tempted to drink: “I’ve been blessed in some way I don’t know. I just had the desire to drink completely lifted from me.”

Laxalt is now attending Georgetown as a government major, minoring in history. His goal after graduation is law school.

He’s still uncomfortable admitting his problem but eventually adds, “Yeah, I’m an alcoholic. I’ll never drink again. I was 18 when all this happened. I want a better life.”

• • •

Alma Viator has been sober for the past 25 years, almost half her life. She now operates Viator Associates, a public-relations firm specializing in theater and political, social, and charitable organizations. Viator is well known in Washington for hosting the premieres of many Broadway productions at the National Theatre and for high-powered opening-night parties at the Old Ebbitt Grill.

Viator remembers clearly the day she decided to stop drinking. It was a Saturday in August 1973 at her house in Bethesda. “I got up, and I spent the day cleaning the house, doing all those normal things. My husband was outside building a patio, and the kids were in the backyard playing.”

At four in the afternoon, she went to the grocery store. “I remember walking in,” she says, “getting bloody-mary mix, putting it in the cart, and going to the liquor store to buy vodka.”

At home she mixed her drink and poured it into a Coke can so her family couldn’t tell she was drinking. She was drunk by dinnertime. Her husband was tired, so he and the children were in bed by nine.

“I then tiptoed down to the basement to have a little party all by myself,” she says. “I went through the bloody-mary mix; I went through the grape Kool-Aid. Then I was drinking it straight while sitting on the basement floor cutting out Family Circle magazine recipes and watching some stupid movie. And I passed out.”

Somewhere around two in the morning, her four-year-old son, Wesley, came looking for his mother. “He found me passed out on the floor. He kept trying to wake me,” she says. “He thought I had died.”

She started to stir, saw Wesley’s frightened face, and said, “God, please help me.” It was her turning point. “I just felt peaceful. I hugged Wesley and took him upstairs and put him to bed. I woke my husband and told him everything. I made him promise to get me some help the next day.”

When she woke up later that morning, Viator panicked. “I really couldn’t imagine wanting to live without drinking. To me it represented all the fun, all the excitement, all the good,” she remembers. “I felt good when I drank, and did not feel good when I wasn’t drinking.”

Viator comes from a family of alcoholics. Her father and six of his seven brothers and sisters were alcoholics. One became sober after getting help, but all the rest, including her father, died of alcoholism.

Viator began drinking in high school while in a play in Augusta, Georgia. “It was a local theater group, and I was hanging out with older people, and I started drinking beer. I loved it right away. It made me feel so smart and so pretty. The first time I went out drinking, I got drunk. I just loved it.”

She left her parents’ home at 16, moving in with a school counselor, and graduated from high school with straight A’s. She says she was drinking only on weekends but always to get drunk.

Viator had dreams of going to college as a theater major. She tells about going to Chicago to audition for a scholarship as a drama major at Carnegie Tech.

“A friend gave me a bottle of wine to take with me, and I drank half the bottle before the audition because I had heard drinking makes you relax, and I thought I’d do better at the audition. Of course I didn’t get the part. They probably smelled it, for heaven’s sake!”

By 17, Viator was married to her first husband, a radio announcer. She put aside a four-year scholarship to Boston University, where she had auditioned sober.

Her husband was not an alcoholic, but he drank with her. “I drank all the way through my first pregnancy. I didn’t smoke, but I drank,” she says.

In 1967, when she was 19, Viator and her husband moved to Bethesda, and she got a job with the phone company. Her drinking became heavier. She soon had another child and by the following year was spending more time with an older woman friend drinking every day and into the evenings, often leaving the children with her husband or a sitter.

The drinking was compounded by prescribed amphetamines and tranquilizers. She would complain to physicians about being depressed and, without asking questions, they would prescribe the drugs.

She believes her children were too young to understand her drinking, but “they did understand that Mommy cried a lot, Mommy was unhappy a lot.”

As Viator looks back on the momentum of her alcoholism, she explains that for years it was possible to get away with things. But then “bad things happened and started piling up and piling up. And things got so out of control, I would decide to cut down on my drinking. I’d quit and was so irritable. I’d say, ‘This is a stupid idea.’ I’d come to town, have lunch with somebody, and start right up again.”

By 1973, Viator says, she realized that her plans of becoming a famous actress or writer, of marrying a politician or an ambassador, had been destroyed.

To get help for her drinking, her husband put her in contact with what she will only call a “self-help program.” At first she admits to being embarrassed at seeking help because she thought she couldn’t be an alcoholic. But in going to meetings, she was faced with the reality that she had all the symptoms of alcoholism.

“I hadn’t gone down nearly as far as a lot of people have to go,” she says. “But I was told that alcoholism is like an elevator. You can get off at any floor. I didn’t have to go down in degradation or kill somebody or end up in jail or a mental institution.”

Being sober was at first frightening, especially at business functions where she had previously been the life of the party. Viator’s life slowly began to move back up the elevator shaft, and she went to work in publicity for Ford’s Theatre.

She remembers a party at the Polish Embassy where she had brought the actress Celeste Holm, who was starring at Ford’s. Viator was not drinking when the cultural attaché came over to ask what he could get for her. Then he said he had something special he knew she would love.

Viator, laughing again, relates, “I’m 26 years old and I’m thinking, ‘Oh my God, I’m going to cause an international incident. I’m going to embarrass Ford’s Theatre by refusing this drink. What am I going to do? He’ll never understand. I can’t tell him I’m an alcoholic.’

“So I just left. I didn’t know how to handle it. I didn’t know what to do.”

Now divorced from her first husband, Viator is married to Ben Jones. She remains active in her alcoholism self-help program and makes herself available to help other alcoholics. She says nearly half her friends are recovering. “Alcoholism knows no gender or race or occupation or social status,” she explains. “It cuts across just like any disease. If you’ve got it, you’ve got it.”

• • •

Morton Kondracke hasn’t had a drink in 12 years. There were moments during his drinking phase when he was convinced he would quit, but the turning point came while he was watching television with his teenage daughter. She heard one of the performers say borracho, Spanish for drunk. “She pointed to me and said, ‘Esta hombre es borracho,‘ ” Kondracke says. “That was like a poker through me. I was humiliated.”

Kondracke is one of Washington’s more recognized journalists, with some 16 years as a panelist on The McLaughlin Group. While he was drinking, he thought he had everything under control. He went to work each day and made his deadlines and television appearances. He drank only in the evenings and on weekends.

Kondracke, 59, is now executive editor and columnist at Roll Call and commentator on the Fox News Channel as well as cohost of the weekly political show The Beltway Boys. He says he drank a little in college, but it really picked up when he covered the Illinois state legislature for the Chicago Sun-Times in the 1960s.

In the state capital, everybody drank a lot: “The state legislators after hours would go and guzzle martinis.” He didn’t start seriously drinking until moving to Washington in 1968 when he came to the Sun-Times bureau, eventually covering the White House.

Kondracke went on to become a columnist for the Wall Street Journal and United Features Syndicate and was briefly Newsweek’s Washington bureau chief before joining the New Republic.

“I think I drank an average of a bottle of wine a day,” he explains, “and on weekends I would drink sometimes six hard drinks before dinner. So by the time we went to the dinner party, I had a buzz on.

“I never drank during the working day. I didn’t start until the day was over and I’d earned the right to let loose. I never had a drink at lunch. I knew a guy at the State Department who carried a cup that had vodka and tea in it, and he had a buzz all day. But I wasn’t that kind of alcoholic.”

Kondracke’s wife, Millie, became concerned about his drinking. “I was functionally not there after about nine o’clock at night,” he explains. “I was not there for her and the kids. And I had a bad temper when I got drunk. I mean I didn’t beat anybody up or throw things around. I was just sullen, and it was too much trouble to help the kids with their homework. It was intolerable for Millie. I wanted to be left alone to sit and watch television.”

Kondracke laughs, “Millie would go on Carry Nation raids and go find all the hidden bottles and dump them out. There were half-gallon jugs of this and that and glug, glug, glug down the drain.”

For a time, he says he even toyed with Antabuse, a chemical that makes a drinker extremely ill if he or she imbibes alcohol. But Kondracke says he only experimented with it to see if he could be a moderate drinker.

When his daughter embarrassed him that night in front of the television, he decided to try AA. He stood up and told his story at the first meeting. “I’m a talker,” he laughs. “And I had sort of a religious experience at the same time.

“I’m an Episcopalian. I think the religiosity of AA helped trigger my conversion, if that’s what you call it–reconversion,” he explains. “There’s something truly profound about the 12 steps. It’s total surrender. It’s self-analysis. It’s making amends to other people. It’s service, but it’s also giving yourself over to a higher power.”

Kondracke had hit his own bottom. It was not the bottom of melodramatic Hollywood movies where the drunk loses his job, his wife walks out on him, and he kills someone in an auto accident. But for him, he had fallen low enough. Kondracke does admit he feels lucky he didn’t kill anyone because “I drove drunk. Coming home from these dinner parties, I would drive through a blur.”

There were no precipitating factors that set off his drinking. “I’m convinced that it’s genetic. My father was an alcoholic,” he explains, “his father was an alcoholic, his brother was an alcoholic. I just think you have a predilection for alcoholism.”

Kondracke is grateful that fortunately his drinking days were over by the time his wife was stricken with Parkinson’s disease. “It would have been terrible during her illness for me to have been a drunk. I wouldn’t have been able to take the kind of care of her that I have been able to.”

Now that drinking is in the past, Kondracke says he can go to parties or be with someone at dinner who is drinking and never feel a craving to drink. Like other recovering alcoholics, Kondracke says he has drinking “beat conditionally.” He might be tempted if something terrible happened in his family or to his job. But, he points out, since quitting, he has changed jobs and his wife became ill, and he survived.

“I’ve thought, suppose I had terminal cancer. Why not go out drinking gin and tonic? I might do that. If there literally were no tomorrow, I might go out drinking. But short of that, I don’t think I will.”

If he’s ever tempted, Kondracke hopes he will call AA, even though he hasn’t attended meetings for a long time. “If I were going to spend money on alcoholism,” he says, “I would spend it proselytizing for AA.”

He swears by the support of the group and believes self-control “with God’s help” is part of the curing process. “The last thing that happens in every AA meeting is that you do the Serenity Prayer,” he says, “and then you say ‘keep coming back.’ It works. It really does work.”

• • •

“Benjamin Schwartz” is a Washington-area doctor who complicated his alcoholism with drug abuse. The 49-year-old physician virtually destroyed his career and is making a painful comeback.

Benjamin Schwartz is not his real name, because even though the employees at the government clinic where he now works know about his alcoholism and drug abuse, he explains that it is dangerous for a doctor to admit he is an alcoholic, even at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.

“If a doctor comes to an AA meeting and says, ‘I was drunk and I didn’t show up at the emergency room and a patient lost his leg,’ they’ll sue me,” he explains. “We have a doctors’ AA meeting for health professionals.”

There’s a melancholy and barely suppressed anger in Schwartz as he tells his story. He can quickly recite his sobriety date: May 10, 1989. But he doesn’t claim it as a badge of honor the way most recovering alcoholics do when they stand up at AA meetings.

“It’s really hard to believe that this is an illness you shouldn’t be ashamed of,” he says. “You shouldn’t be ashamed of it? You shouldn’t be ashamed of taking your nice medical-school degree and screwing up and losing your practice that was grossing close to a million dollars a year and instead working as an hourly consultant at a crappy little falling-down military clinic? . . . It took me five years before I could comfortably tell people what I did for a living.”

His drug and alcohol abuse, Schwartz says, embarrassed and humiliated him. “I’ve lost all my friends, my entire peer group. Everybody. I haven’t continued with one of them.”

Schwartz grew up in Montgomery County and, like so many other alcoholics, began drinking in high school. He drank to get drunk. “That was the point,” he adds, surprised anyone would drink for any other reason. He remembers that at his girlfriend’s 18th-birthday party, he thought it was perfectly rational to celebrate by drinking 18 beers. “Can you imagine,” he asks, “drinking 18 beers?”

After high school, Schwartz went to the University of Rochester, where he used marijuana every day for six years. In residencies at the University of Michigan and the Medical University of South Carolina, he moved on to prescription drugs. Eventually, he established a medical practice in the Washington area.

By the time his drug and alcohol problems came to a head in 1989, Schwartz, then 39, was using opiates. “I was using the medications that the salesmen would leave as samples in my office. Things with codeine, like headache medications. I’m sure everyone in the office knew. I guess I thought I was being cagey.”

When asked if he made any serious mistakes as a doctor while under the influence, Schwartz says, “Not that I know of. Clearly you can’t have the right judgment if you’re impaired. There’s no way you didn’t make mistakes. You can’t know what decision you would have made had you been in another state of mind.”

But he does admit that he carelessly overprescribed narcotics to his patients. “I was indiscriminate about that. I really didn’t care if people got habituated to narcotics,” he says, “because I was prepared to keep giving it to them. . . . The DEA got wind of [patients’] selling drugs and looked at the bottle, and it had my name on it, and they went to the pharmacist and said, ‘Does this guy prescribe a lot of this stuff?’ They saw me as a loose cannon, indiscriminately putting narcotics out into the community.”

The DEA’s concern soon became moot. By the time agents confronted Schwartz, he had hit bottom. The medical partnership had fallen apart, and he wasn’t writing any more prescriptions. He had also called out to a physician friend for professional help, asking whether she knew a psychiatrist who handled addiction problems.

She called the Talbott Recovery Campus in Atlanta, which has a recovery program tailored for physicians. He was booked there almost before he knew what was happening. Schwartz went to Atlanta full of rage. “I though it was a railroad job and it was just a way for them to make money for themselves. They tell you it’s going to be a three-day evaluation,” he says, “and everybody’s there for four months. You tell people, ‘I’m just here for three days,’ and everybody goes, ‘Yeah, that’s what they told me.’ ”

During his four months in the program, Schwartz’s partner dismantled the practice and took all the money out without paying the bills, a problem Schwartz discovered when he returned home.

Nonetheless, Schwartz was able to stay sober. He says there is a high recovery rate for physicians with alcohol and drug problems because the medical society in most states requires weekly urine screenings for drug or alcohol usage and a minimum number of AA meetings before a doctor’s license can be restored.

When Schwartz started job hunting, he began to realize how difficult it would be to start over. It wasn’t until he found the government clinic where he works that he could return to medical practice.

As for his family, Schwartz says he hadn’t realized what they went through while he was at Talbott. His wife was left alone, fighting bill collectors and finding that their friends were unsupportive. His daughter, now away in school studying opera, gained a lot of weight.

Schwartz doesn’t know if he’ll ever be able to have a private practice again, but he has become active on the state medical board that handles physicians with drug or alcohol problems. When he confronts doctors with such problems, he tells them he has a list of three places where they can go for treatment. If they refuse, they won’t be practicing tomorrow. That ultimatum, and the treatment doctors can afford, gives physicians a 60- to 70-percent recovery rate, he says. The recovery rate for the general public is less than 10 percent.

Schwartz says he knows he will never drink again, but he’s worried about narcotics he might need for medical purposes. He went to a dentist and was given a painkiller with no dire consequences. “I told the dentist, ‘That’s a really good drug. I took it for years, but I never took it for pain.’ ”

This article appears in the March 1999 issue of The Washingtonian.