They ruled the scene with no less authority than the President. Diners flocked to their restaurants, attracted in large measure by their power and allure.

Not chefs—maître d’s.

Five decades ago, the idea that chefs could be celebrities was unthinkable. Almost without exception, they were rarely seen or heard, commanding their large, brigade-like operations behind closed doors. It was the maître d’—sometimes the restaurateur, sometimes not—who was the face of the restaurant. The defining features of Washington’s best dining rooms were that they were French—Sans Souci, Rive Gauche, La Bagatelle, La Niçoise—and they were fronted by charismatic men who commanded the host stand as if it were their fiefdom.

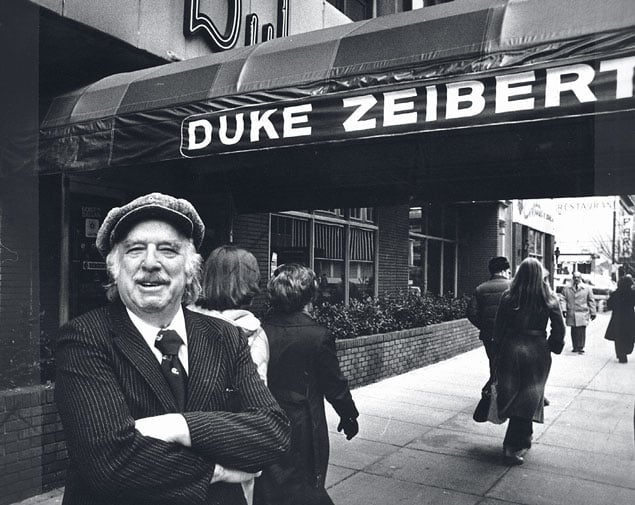

The scene today is full of TV-dreaming chefs who veneer their teeth and submit to media training, but none rivals the spirit of Duke Zeibert, a gregarious figure who for more than 40 years welcomed politicos, entertainers, and athletes into his restaurant as if it were a nightclub. At full tilt, Duke Zeibert’s was a buzzing hive of dealmaking, networking, and excess, an irresistible combination of Elaine’s and Sardi’s but livelier, somehow, than either.

If Zeibert was the backslapper, Paul DeLisle was the gatekeeper—and the unofficial dean of maître d’s. A former British Embassy dishwasher, DeLisle rose through the ranks, eventually landing at Sans Souci, near the White House, where in his 16 years as maître d’ he earned the title “second most powerful” man in Washington from the Washington Post. Among those he barred from entry were Mick and Bianca Jagger—they showed up without a reservation, and Mick was tieless. DeLisle was devoted to his regulars, including Art Buchwald, George McGovern, and Ethel Kennedy. He let Henry Kissinger into the kitchen to take phone calls.

After Watergate, the mood became more subdued, and by 1979 a man named Jean-Louis Palladin had arrived from France and the ground began to shift. Palladin was every bit the presence that DeLisle was, if not more so. He was also something new: a chef who, with his impish smile, rock-star mane, and revolutionary ideas of local and seasonal, dared to stand out, giving the area its first celebrity chef and setting the stage for the next three decades.

This article appears in the November 2013 issue of Washingtonian.