Justin Bunce struggles into the conference room dragging his left leg, using a cane, and looking as if he’d rather be somewhere else. He sits at a long table with members of a Traumatic Brain Injury medical team at National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, awaiting their questions as part of his intake evaluation.

Bunce, 27, appears distracted. Despite lots of medications, he’s often unable to concentrate. He has had short-term-memory loss ever since an improvised explosive device (IED) planted in the wall of a cemetery detonated while he was on foot patrol in the Iraqi city of Husayba, near the Syrian border, in March 2004.

Shrapnel riddled his body, broke his leg, and ripped into the right frontal lobe of his brain and his right eye, leaving him effectively blind in that eye. At the time, he was a lance corporal in the Marine Corps, which he had wanted to join since his freshman year at Centreville High School in Fairfax County.

“What’s the toughest branch of the service?” he had asked his father, Peter, an Air Force colonel and career military man.

“Physically, it’s the Marines,” his father said. “There’s not even a close second.”

From then on, Justin Bunce never wavered. He became a workout fanatic and played rugby in high school so he could become a great Marine. Part of an elite unit in Iraq, he was one of the first Marines to engage in night fighting. “When I was in combat in Iraq, I was on cloud nine,” he says. “I was where I wanted to be.”

Following his first Iraq tour, during which he survived many firefights, he was called up for a second—which turned out to be his last.

After his injury, Bunce wound up at National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda. When he learned that the commandant of the Marine Corps was coming to pin a Purple Heart on him, he resolved to be at his best.

He asked his dad to shave him and put a Marine Corps uniform shirt on him. When the commandant entered Bunce’s room, Bunce shifted his legs off the edge of his bed, pulled himself up, and, straining to maintain his balance, stood at attention as the commandant pinned on his medal.

• • •

His hair trimmed short, wearing a robe, and with a black patch covering his right eye, Bunce asks for a cigarette as he sits down at the table for his intake evaluation in March of this year. He knows his request won’t be granted.

He looks up when Dr. David Williamson, a neuropsychiatrist and director of the Inpatient Traumatic Brain Injury Program, enters the room. Bunce reaches over with his right hand to clasp the doctor’s hand and says, “Aye, laddie,” mimicking Williamson’s Scottish accent. Williamson, a civilian, smiles and withdraws from the room.

The initial impetus to create the Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) unit—usually referred to simply as 7 East, for its location in the medical center—arose in 2005 after the Marines entered Fallujah and suffered some traumatic brain injuries during the intense fighting there. Four years in development, the unit opened in early 2009. The 7 East team has experts in neuropsychiatry and neuropsychology as well as speech, physical, recreational, and occupational therapy. The unit is the only one of its kind anywhere; with just six beds, it can accommodate only a small percentage of those in need of it.

This troubles Cheryl Lynch, founder and executive director of American Veterans With Brain Injuries. Her son Chris, an Army paratrooper, suffered a near-fatal brain injury when he fell 26 feet in a training accident in 2000. Since then, Chris has seen countless doctors in his search for treatment for his mood swings, violent outbursts, and bouts of bizarre behavior, which sometimes grew destructive when he was prescribed the wrong medication. His mother says her son’s treatment at 7 East has significantly improved his behavior.

“The expertise Dr. Williamson and the staff at 7 East provides is unique—they are making a big difference with Chris,” she says. “But this level of care should be available in all our Department of Defense health-care systems for all returning servicepeople with TBIs. The country owes them that.”

TBIs have been called the “signature” injury of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. They frequently happen when metal fragments from high-energy explosions penetrate brain tissue or when blast waves traveling at 1,600 feet per second hit the brain, rupturing blood vessels and tearing tissue. Bunce likely suffered from both.

A 2008 RAND Corporation study found that 20 percent of the 1.6 million US military personnel who had served in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2001—320,000 in all—had suffered some form of combat-related brain injury, including TBIs, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These numbers make clear that the cost of the wars will continue long after they have ended.

“Our mandate and area of expertise is to understand and treat these injuries,” says Williamson, who received his psychiatric training at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and the University of London. “The sad fact is that the wars are driving an increased knowledge of brain injury. Because of the body armor they wear and the rapid intervention and evacuation, many soldiers who would have died in earlier wars now survive potentially lethal brain injuries.”

In response to questions from Army captain David Lee, a psychiatric intern, Bunce, slouching in his chair, describes his family and background. As he talks, his head sometimes slumps forward and he nods off.

“How well are you sleeping?” Dr. Lee asks.

“I hardly sleep at all,” Bunce says. He reports pain in his head, neck, back, and limbs and can’t sleep at night.

Even when he doesn’t nod off, Bunce’s short-term memory is so compromised that he often forgets the questions Lee poses.

“Could you repeat that?” he asks several times.

One day in October 2004, seven months after his injury in Iraq, Bunce was driving to Gettysburg to meet members of his Marine unit home on leave when he lost control of his car. Knocked unconscious in the one-car accident, he suffered additional brain damage. Doctors asked his father to be ready to make a decision about taking him off life support because they held out little hope for his recovery. Justin has no memory of the accident. It’s possible he suffered a seizure.

His father didn’t know that Justin, despite the brain injury and only one functioning eye, had gotten behind the wheel to drive. He thinks his son was motivated to see his Marine buddies because, like many injured servicemembers, he wanted to rejoin his unit and redeploy to Iraq, an impossibility given his combat injury. For a time, Justin refused to take prescribed drugs because he felt doing so would diminish his chances of returning to duty.

At the Hershey Medical Center after the accident, Justin suffered a severe infection that antibiotics eventually brought under control, but not before it had caused additional loss of brain tissue, especially in the right hemisphere. When Williamson examined Bunce’s brain scans from before and after the car accident, he concluded that the accident and infection had caused more extensive damage than the IED explosion.

Before coming to 7 East, Bunce lived for more than a year in a group home in the Shenandoah Valley for people with disabilities, but he says the place did him no good: “There was no therapy there—everything was outsourced.”

Besides short-term memory loss, the trauma to Bunce’s brain caused paralysis in his left arm and leg and produced personality changes that remain unresolved.

“Most of Justin’s right frontal lobe is gone, and part of his left frontal lobe is gone as well,” Williamson says. “This is a very severe traumatic brain injury that causes him to have chronic problems with attention, memory, impulsivity, organization, and, on top of that, bad judgment as well as personality and behavior changes.”

His father says that on many occasions Justin has stepped into the street without looking for oncoming cars. He often acts as if the normal restraints that govern social behavior have been stripped away.

• • •

During his intake interview, Bunce fixates on an attractive medical student sitting across the table from him. He stares at her and asks if she’s available. She politely fends off his advance. After more edgy banter, Bunce realizes that his efforts are going nowhere.

“You’re very distracting and I can’t stop looking at you,” he tells her. “Could you please move from that chair so you won’t be in my line of vision?” She moves a few seats away.

His approach to women remains unchanged. A few days later, he tries to hit on a female chaplain in an elevator.

Later in the interview, he asks for the numerical code that opens the exit door from 7 East, presumably to get out to buy cigarettes. Dr. Lee refuses.

“I will haunt your dreams,” Bunce tells him in a heavy voice leavened with a trace of humor. He seems to enjoy making idle threats. A few days later, agitated after again being denied a cigarette, he tells members of the staff that he plans to stage a “bloody coup” and take over 7 East. He’s joking, but there’s an edge to his humor. He really wants cigarettes, he says, “because I need the stimulation of nicotine to wake up.”

As the intake interview proceeds, Bunce’s head droops again; he struggles to stay awake and remember the questions. Then, toward the end of the interview, the subject of movies comes up and he begins quoting lines from his favorite movie, The Big Lebowski.

Suddenly alert and animated, he laughs and repeats more dialogue from the film. It’s almost as if he’s a different person.

As Bunce leaves the conference room, someone mentions a line from the movie. Bunce turns and corrects him, then proceeds to recite the dialogue from an entire scene.

Despite the extent of his brain injury, Bunce is oriented to time and place and is aware of his surroundings. He comes across as an intelligent person with a sharp sense of humor and excellent verbal skills. Williamson attributes Bunce’s ability to verbalize so well to the fact that he’s right-handed, which means his language abilities reside in his left brain. If he had the same amount of damage to his left brain as to his right, Williamson says, he would have lost most of the language ability he now has. The fact that Bunce thinks, talks, and functions as well as he does is a testament to his and his brain’s resiliency.

“Considering what has happened to him, I got a lot more of Justin back than I ever thought I would,” says his father. “His judgment is lacking, but he can still love and laugh.”

In the days following his admission to 7 East, it becomes clear that Bunce’s refusal to do much of anything will be an obstacle to treating him. Williamson says many soldiers with traumatic brain injury suffer from a condition called amotivational syndrome. One soldier who had been shot in the head did virtually nothing voluntarily—he once stood still for 45 minutes holding a glass of water in his hand until someone told him to put it down.

Before his brain injury, Bunce relished challenges, but he now resists them. When a staff member offers a helpful suggestion, he answers: “You can’t tell me what to do.” Once proud to wear his Marine dress blues, he scuttles disheveled down the hall in a robe. He submits to showers only under duress and never wants to brush his teeth. The lack of self-motivation is a mystery to Williamson.

“Justin has spent at least five years in residential placement trying to make his way forward, but he’s been stuck and we’re trying to discover why he’s stuck. We need to find out if his poor performance on daily tasks such as personal grooming, his lack of motivation, his inability to sleep normal hours or keep his therapy appointments is caused by his impairment or is volitional.

“He is a very complex patient, one of the most challenging cases I’ve ever seen,” says Williamson, who has been treating traumatic brain injury for more than 20 years. “It’s much easier to deal with someone who has lost a limb than with someone who has suffered severe emotional or cognitive deficits because of a traumatic brain injury.”

• • •

The human brain is the most complicated organ, and arguably the least understood. Despite decades of research, the physiology of the brain—its role in reasoning, writing poetry, composing music, solving mathematical problems—remains a mystery.

From neurobiology we know that the brain’s frontal lobe, the part of Bunce’s brain struck by shrapnel, is where decision-making and judgment and other so-called executive functions are carried out. In all likelihood, this is why Bunce is so impulsive and unable to make sound judgments.

But why and how certain brain injuries alter brain chemistry and structure to trigger changes in personality and character isn’t clear. No two brain injuries are the same or produce the same results, and no brain scan definitively explains why someone behaves the way he does following a TBI.

“You cannot look at someone’s brain scan and determine how an injury will impact a patient’s personality or behavior,” Williamson says. “You can only determine that when you fully assess the patient.”

The case of Phineas Gage provided the earliest clues about the relationship between brain injury and personality changes. Gage had been working as a railroad-construction foreman near Cavendish, Vermont, in September 1848 when an explosion drove a tamping iron measuring more than three feet long and 1¼ inches in diameter into Gage’s cheek, up into his forebrain, and through the top of his head.

By some miracle, Gage survived. After recovering, he wanted to return to his job, but the contractors refused to rehire him because he had undergone a personality change. Once the company’s most capable and efficient worker, he had become impatient, rude, obstinate, and profane.

Gage went on to take odd jobs—appearing for a time at Barnum’s American Museum in New York City—until his death in 1860. The details of his case were published by Dr. John M. Harlow, his treating physician, in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal.

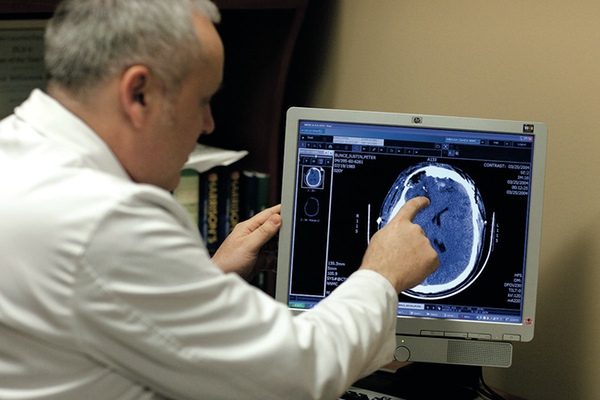

On an MRI scan of Bunce’s brain, Dr. David Williamson, director of the Inpatient Traumatic Brain Injury Unit at Bethesda’s National Naval Medical Center, points out that most of the right frontal lobe and part of the left frontal lobe are destroyed, resulting in problems with attention, memory, organization, judgment, and more. Photograph by Chris Gavin Jone.

An ongoing problem with brain-injury patients is the large number of prescription drugs they acquire over time. This happens because they’re prescribed one or more to address whatever complaint they have when they visit a veterans’ hospital or see a physician.

To get a clearer picture of an injury’s impact and to separate that from the influence of medications, Williamson and his 7 East team often take his patients off all pharmaceuticals. That’s what he does with Justin Bunce.

“We need to get a baseline to see what is there,” Williamson explains.

Bunce showed “unquestioned improvement” soon after he came off the drugs, his father says. He began to think more clearly and his humor lightened. This was likely a result of getting off some pain medications that are known to dull thinking. Williamson also discovered that Bunce’s antidepressants, which he had been taking for years, caused him to become agitated and intrusive.

Williamson sees modest improvement in Bunce’s short-term memory since he stopped some of the drugs, but he says a difficult road lies ahead. “Unfortunately, there is no good drug to enhance memory,” he says, “so I don’t know how much more his short-term memory can improve. But I think the real key to Justin is unlocking the motivation that we know was once there.”

The question is how to do that. What combination of behavioral programs and medications might get Bunce unstuck?

Williamson tried Bunce on a low dose of the amphetamine-like stimulant Adderall, often prescribed for hyperactivity, to treat his problems with focus and concentration. He detected some improvement and gradually increased the dosage. At the same time, neuropsychologist Jennifer Lundmark organized Bunce’s daily life into a “behavior contract.” For every hour of Bunce’s day, the 7 East staff audits his compliance with certain goals that include personal hygiene, attending all his therapy sessions, being courteous, and avoiding sexually inappropriate talk or touching.

Every hour, the staff asks Bunce to grade himself on his compliance. If he doesn’t fully comply, he receives demerits and loses privileges. If he does comply, he’s rewarded. After some fits and starts, Bunce is following the program with reasonable success.

One reward for Bunce is allowing him to smoke. “I hate to make smoking a reward for compliance,” Williamson says, “but sometimes we need ways to get him to do things we want him to do for his own benefit.” Another reward is allowing him to go off campus to see a movie.

After Bunce has been an inpatient for nearly a month, the behavior contract appears to be working. He is doing “much, much better,” says Williamson. “Justin is now tidying up his room, he’s taking care of his personal hygiene, and he’s going to bed on time. He used to stay awake until 3 AM, but now it’s lights out at 10 PM. One of his rewards for compliance with the behavior contract is to let him keep his light on until 11. We’ve also had no problems in the past few weeks with social or sexual improprieties, and he’s developed a social life on 7 East. He’s more awake and alert and very much engaged in the behavior contract.”

• • •

Peter Bunce sees dramatic improvement in his son’s alertness and awareness.

“Justin has become much more cheerful and less impulsive—even his posture has improved,” his father says. “He also interacts a lot with people on the unit, and he did not do that when he first arrived. In fact, he makes it his mission to make the other guys laugh. One young man there who suffered a severe brain injury from a gunshot to the head does not say much at all, but when Justin gets with him he can get him laughing. It’s a wonderful thing to see.”

Bunce’s pain has been reduced through medication and biofeedback, and there are ongoing attempts to improve his walking ability. He has visited the gait laboratory at Walter Reed, where computers analyzed his gait. Besides finding ways to improve Bunce’s balance and walking, the gait lab also revealed that he didn’t need further surgery on his foot, as had been recommended by some doctors.

Williamson says Bunce had been a “gifted artist” before his injury, and he wants to engage him more fully in that. Bunce’s artistic gifts apparently weren’t lost with his brain injuries, and they may someday open a door for him to do graphic-design work.

Williamson says Bunce’s progress has been so remarkable that the unit is now trying to figure out the next two years of his life—what he’ll do and where he can live. Bunce expresses a desire to marry and have a family, and the 7 East staff uses that as a carrot to motivate him toward a more independent life.

“We’re linking what we do here to Justin’s leading a better life for himself,” Williamson says. “That’s a lofty goal, and we remind him of that.”

Bunce remained at 7 East for several weeks of evaluation and therapy to provide him with structure and consistency unavailable outside. The real test, Williamson says, comes now that he has been discharged.

“That is when you face real life with all the stresses and challenges you did not face in the hospital,” the doctor says. “That’s where you see the real impact of a brain injury.”

Neither Williamson nor Bunce’s family members think he’ll be able to live independently, but Williamson believes he’ll be able to lead a much more productive and fulfilling life than he does now.

NIGHTMARE IN RAMADI

Nearly five years after the ambush, a Marine still battles the demons of PTSD

• • •

K.C. Schuring is alone, lying on his back in the heat and dust of a street in Ramadi, Iraq. Blood streams down his forehead into his eyes from a bullet that pierced his Kevlar helmet. It felt as if he’d been beaned with a fastball, but he remained conscious and upright until more automatic fire shattered his left femur, or thigh bone, and slammed into an armor plate on his back and broke two ribs. The bullet that tore through his helmet pierced the skin on his skull before exiting but didn’t penetrate his brain.

It’s late morning. Lying on a dirt road, Schuring moves his eyes and realizes the street is deserted. He doesn’t know where his men—19 Iraqi soldiers and two US Marines under his command—have gone. They were on foot patrol when they rounded a corner of a city square and walked into a blaze of gunfire.

He knows the insurgents who ambushed his platoon are watching. He knows if he moves they’ll shoot at him again. More than death, he fears capture and imagines being paraded before the media, appearing on the Al Jazeera network, or his wife seeing him beheaded on television. So he remains still. And waits.

Looking through a narrow opening in the corner of his helmet, Schuring sees a man with a short beard peeking around a corner of a building some 50 yards away. One of the ambushers. Schuring knows that the man wants to strip him of his gear and weapons.

After a quick glance, the man ducks back behind the building. When he does, Schuring slowly maneuvers his rifle into firing position. A few minutes later the man, wearing sandals and carrying an AK-47, steps out into the street and edges toward Schuring.

The insurgent realizes too late that Schuring’s M-16 is aimed at him. Schuring stares into the man’s surprised eyes as he fires. Bullets rip into the Iraqi’s head and he drops like a marionette whose strings have been cut.

A few moments later, a second insurgent runs out to aid his compatriot. He fires his AK-47 wildly, spattering shells against an adobe wall behind Schuring, who stitches him with bullets to the chest and head. The man falls dead. Schuring keeps firing to dissuade any other insurgents from coming after him, emptying a magazine and a half of 40 rounds. He thinks of tossing a hand grenade but doesn’t have the strength to remove it from his bag. If he had, he realizes later, he might have blown himself up. He takes out his 9-millimeter handgun and holds still. He looks at his watch—he always looks at his watch so he can call the incident in to headquarters. He’s been down less than ten minutes.

Schuring is unable to move, the pain in his leg and head nearly unbearable. But he’s at peace when he tells himself: I did my job here, and now it’s time for me to die.

• • •

Schuring wakes up sweating, his heart pounding as his wife, Lynn, struggles to free herself from the chokehold he has on her neck. He’s back home in Michigan, thousands of miles from that dusty street in Ramadi, but in this recurring nightmare he never left.

Schuring suffers from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), one of the most florid cases Dr. David Williamson has ever seen. Schuring has been treated by the 7 East team before, and in March of this year—4½ years after being evacuated from Ramadi—he traveled from his Michigan home to see if the doctors in Bethesda could help him again.

Now 42 and a lieutenant colonel on active duty in the Marine Corps, Schuring grew up near Kalamazoo, where his family ran a bedding-plant business. A star football player in high school, he earned his BA from Hope College in Holland, Michigan, where he majored in art history and biology, was on the football, lacrosse, and track teams, and met his wife, a special-education teacher. They married in 1992, the year after they graduated.

Schuring had undergone training at officer’s-candidate school for two summers during college and graduated as a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps. He chose the Marines, he says, “because it was harder, a way to prove myself.”

He reported for active duty after college, but during the military downsizing in the 1990s he transferred to the reserves and found a job in quality control in the auto industry. He earned an MBA from Madonna University in Livonia, Michigan, in 2001.

With the 9/11 attacks, he knew his unit was likely to be called to active duty, so he trained it for combat. After the invasion of Iraq, he used the Rosetta Stone method to learn Arabic before deploying in 2006. Though not fluent, he knew enough to ask questions and to get the gist of what Arabic speakers told him.

In Iraq, then-Major Schuring helped train Iraqi soldiers, whom he still considers “the bravest people I met,” noting that they and their families lived under constant threat from al-Qaeda. He was stationed at an Iraqi army base called Camp Defender in Ramadi, a place he likens to the Wild West. He led regular foot patrols and once found a cache packed with two tons of plastique explosive, detonators, artillery rounds, and other weaponry.

“We were attacked virtually every day,” he says. “You never felt safe. You could never relax your guard, not for a minute.”

On November 14, 2006, the day he was shot, the Iraqi and American troops under his command scattered when the ambush began, and they assumed Schuring had fled with them. When they realized he hadn’t, they returned and pulled him into a walled courtyard to avoid more gunfire. A Navy corpsman bandaged his head and called in Humvees to transport him to a base hospital.

Despite the fairly rapid medical interventions, Schuring came close to losing both his left leg and his life—he had a near-death experience when he suffered cardiac arrest from blood loss. His PTSD began soon after he returned to the United States.

“I starting having terrible nightmares of what happened to me in Ramadi and of all the death and devastation I saw over there,” he says. “It seemed so real to me.” More than once he awoke and got into a combat stance, yelled, and slammed his fist into the headboard. “One time I punched Lynn while I was asleep,” he says. “It became risky for her to sleep in the same bed with me, so we agreed it was best for her not to.”

Schuring’s Iraq experiences invaded his waking life as well as his dreams. He sometimes experiences what he calls “daymares,” when something triggers a violent memory. He starts to sweat, his heart races, and he’s transported back to that street in Ramadi.

“One moment I’m bored, and the next I’m in the middle of a firefight,” he says.

With the PTSD, Schuring was gripped by chronic anxiety—he sensed danger everywhere, even in suburban Farmington Hills. He lived in the same state of hypervigilance as he had in Iraq, where he made rapid life-and-death assessments, often deciding on the spot whether an Iraqi on a street was friend or foe.

At home, he continued to mentally profile people to decide whether they meant him harm. Even now, when he hears a loud noise his body prepares to fight. At restaurants, he insists on sitting with his back to the wall so he can see people who enter.

Schuring descended into a major depression. He withdrew from people—his wife, children, parents, and brothers. He didn’t want to leave home except to go to work. Some days he didn’t want to get out of bed.

• • •

Part of Schuring’s depression stemmed from his feeling that he’d let down the men in his unit by getting shot, a feeling shared by many wounded warriors. It pains him that he won’t be allowed to join them when they deploy to Afghanistan later this year.

To date, he’s undergone 27 surgeries, including having steel rods inserted in his leg to stabilize his femur. Injuries to his pelvis required that he get an artificial hip.

Williamson believes Schuring’s chronic pain and disability are interrelated with his depression. Schuring agrees. “I had been a triathlete and had run marathons,” he says, “and now I was using a walker. It has been very hard to for me to deal with.” He says that during some low points he thought he might be better off if his leg had been amputated.

Schuring also suffers short-term memory problems and mild aphasia caused by the concussive head injury he suffered when the shell struck his helmet. This frustrated him; he sometimes lashed out when his children—son Christian, born in 1998, and daughter Carolynn, born in 2001—corrected him.

Schuring’s irritability sometimes escalated into rage. “Anger started seeping into me, and I had not been that way before I went to Iraq,” he says. “I was a happy-go-lucky person. But when I drove to work, I’d see people in luxury cars and I’d tell myself they did not appreciate those of us who served. Look what we did for our country, look at what we sacrificed, I’d tell myself as I began to boil inside, and you people just don’t care, do you?

“If someone cut me off, I’d get so enraged I’d follow the car until the driver stopped, and then I’d get out of my car and confront him. One time when I thought some guy made a crude gesture to my wife in a parking lot, I stormed over and grabbed him by the lapels. My wife got me away from him before I did anything that might have landed me in jail.”

At six-foot-three and 220 pounds, Schuring is a formidable man. Fortunately, no one he confronted took up his challenge to fight.

In the two years after his injuries, Schuring, ever the Marine, kept telling himself he could “get over” his PTSD and other psychological problems even as they became more intractable. Prescribed narcotics for his leg and hip pain, he sometimes took an extra dose to dull the emotional pain.

During treatment at the naval medical center, Schuring and ten-year-old daughter Carolynn spend time at a computer in one of the rehabilitation rooms. Photograph by Chris Gavin Jones

Schuring arrived at Bethesda’s National Naval Medical Center in the fall of 2008 for more orthopedic surgeries on his injured leg and hip and met neuropsychiatrist David Williamson. As part of a hospital policy, Dr. Williamson’s team routinely consulted with wounded warriors who came to the hospital to determine if they had psychological issues. A man with a warm smile, quick laugh, and firm handshake, Schuring professed to be fine. But as the two men talked, Williamson realized Schuring suffered from PTSD as well as anxiety and depression. He prescribed medications.

That Schuring suffers from an anxiety disorder and depression isn’t surprising, says Williamson: “There is a strong linkage between the two and with PTSD as well. We think all three are biochemically linked in the brain. We also know depression is the mental disorder most associated with anger and violence.”

Schuring at first refused to take antidepressants. “You’ve got to take them,” Lynn Schuring told her husband, “because you’re not the same guy who left for Iraq two years ago.” He relented, and in time his depression lightened, as did his anger and anxiety, but his PTSD didn’t respond as well.

“PTSD is a very misunderstood condition,” says Williamson. “The biochemistry of PTSD is a very old evolutionary phenomenon that is vital for our survival. It allows us to learn from experiences and recognize a dangerous situation if and when we confront it again. Essentially, PTSD is tied into the system in the brain involved in learning and is basically a corruption of something normal that happens in the brain.

“When we confront something that evokes fear in us, a fight-or-flight response triggers a physiological reaction that is anatomically linked to the brain’s memory system. When fully activated—as it is in combat situations—what triggers it is so powerfully imprinted on the mind it becomes almost indelible. These kinds of experiences remain far more vivid and persistent memories than something that happens in the ordinary course of life.”

The brain’s response to extreme stress is a critical part of the imprinting and alters how we record stressful events, Williamson says: “The heightened emotional coloring of events makes for much more ingrained memories.”

That’s why many of us have such vivid recollections of where we were and what we were doing when a traumatic event occurred such as the loss of a loved one, the terrorist attacks of 9/11, or, for those old enough, the assassination of President Kennedy.

• • •

With Schuring and many other combat veterans and servicemembers, these powerfully imprinted memories spring into consciousness from stimuli that might go unnoticed by other people—a loud noise or a scene in a war movie. For some veterans, seeing a plastic garbage bag on the side of the road evokes fearful memories of IED explosions. Many become alarmed driving under a highway overpass. For Schuring and other PTSD sufferers, vivid and disturbing memories, whether in dreams or when fully awake, reengage the fight-or-flight response and emotionally transports them back to the combat theater.

“They sense the same danger and go back to that time and place, and there’s a big arousal of their nervous system and physical changes,” Williamson says. “They begin to breathe rapidly, their heart pounds 150 times a minute, their muscles are tense and tremulous and ready for maximum exertion as epinephrine breaks down carbohydrate stored in the muscles. It activates areas of the brain to allow them to reach peak performance and speed up their reflexes and cognitive process.

“There are changes in the body’s blood-flow patterns,” Williamson says. “No blood goes to the GI tract, because you don’t need to be digesting food when you are about to fight—you need to get the blood to your brain and muscles. [PTSD sufferers] hyperventilate, feel nauseated, and sweat heavily.

“It’s one thing for this to happen in a combat situation, but it’s another when it happens while they’re in their living room holding a two-year-old on their lap or driving in a car with their family. Some people become so gripped by these PTSD episodes and depression that they become social hermits, which is what happened to Lieutenant Colonel Schuring for a while.”

Statistics vary on how many soldiers fall victim to PTSD. A study published in the June 2010 Archives of General Psychiatry found that, of 18,000 Army and National Guard soldiers contacted between 2004 and 2007, 8.5 to 14 percent had PTSD or serious depression and 23 to 31 percent experienced some impairment from these disorders. The Department of Justice has awarded the University of Connecticut a $750,000 grant to study more than 13,000 soldiers from Connecticut who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. The researchers project that 40 percent of those who served will develop PTSD and at least 50 percent of those will have anger issues.

Combat isn’t the only cause of PTSD. Some servicemembers who treat the wounded or are detailed to prepare dead soldiers to return home also fall victim. The Justice Department funded the study to see if there were ways to decrease dysfunctional behavior and lawbreaking among veterans with PTSD.

Williamson suspects that the actual number of soldiers suffering from PTSD may be higher than studies show because many returning servicemembers don’t recognize the symptoms and don’t admit having it: “If you ask these veterans how they’re doing, they say, ‘I’m fine, Doc,’ just as Lieutenant Colonel Schuring did at first. Only when you continue questioning them do you find out they are having difficulty with PTSD symptoms.”

A RAND Corporation study of combat-related brain injuries in the war on terror noted that many servicemembers don’t seek treatment for psychological illnesses because they fear it will harm their careers.

Outside of the expert care rendered at 7 East, the treatment for PTSD in the military appears hit-or-miss, according to the RAND study. Only half of the servicemembers who asked to be treated for PTSD or major depression received what the study considered “minimally adequate” care.

By some estimates, the military medical system has failed to diagnose brain injuries in tens of thousands of US soldiers who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. This may in part explain why in 2009 and 2010 more US servicemembers and veterans killed themselves than were killed in combat in both wars.

• • •

Schuring will return to Washington and continue treatment. Williamson has gotten him into two intensive three-week pain-treatment programs at the National Intrepid Center of Excellence for the care of critical brain injuries, which opened last year on the campus of National Naval Medical Center. It treats and houses 20 patients at a time.

Schuring will undergo an intensive round of acupuncture for pain relief. He received five successful treatments at Navy Med on his last visit. The acupuncture worked so well, he says, that he was able to go off the narcotics he’d been taking for four years. “On a scale of one to ten,” he says, “my pain was a seven, and now it’s a three.”

Reducing the pain has allowed Schuring to resume exercising, which in turn lets him sleep better and be more alert during the day.

To try to reduce his PTSD episodes, Schuring also will take part in a newly developed holistic approach to PTSD treatment at Walter Reed Army Medical Center this spring. The three-week program involves diet, exercise, meditation, and other non-drug approaches.

Williamson hopes the two programs will help Schuring get his pain under better control and “achieve a level of serenity that he does not yet have.”

Schuring says even members of his family don’t understand what he’s been through or the effect it’s had on him: “The military people I work with understand what combat can do to you, but not civilians. We used to have friends who were the parents of kids at the same school our kids attended. We went out to dinner together and did things like that, but we don’t have those friends anymore. They don’t understand what happened to me there. They just know I now have issues they would rather avoid. It’s painful for my wife and me not to have them as friends any longer.”

Because of his injuries, Schuring soon will leave the Marine Corps and return to civilian life. “In the years ahead, I hope to live with my demons and function better,” he says. “I function pretty well now. I’m no longer a shut-in, and I’m on active duty. I have a security clearance, and I would like to do intelligence analysis and stay in tune with the military.

“I want my work to serve a larger purpose than making widgets. I want to complete my mission. I want to help this country remain free and maintain our way of life. I still have something to offer.”

This article appears in the September 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.