One of my earliest memories is from a spring evening when I was four. My older brother, Jerry, and I sit on one end of the couch in our living room. Something is wrong with Peter, our younger brother. Our parents are rushing around making phone calls. A doctor who lives down the street comes over to examine him. He lays Peter on the pale-green carpet. Mom is screaming. They speed off to the hospital.

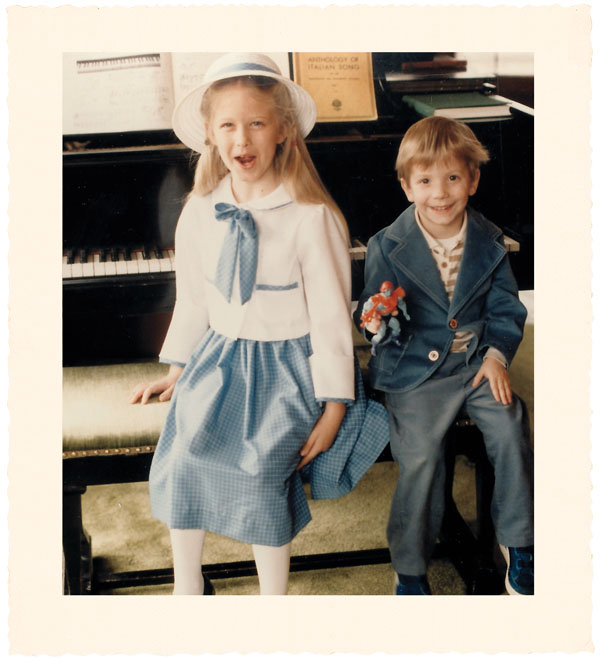

My parents wanted five or six kids. When they learned they couldn’t conceive, they decided to adopt. They had to wait four years before they got Jerry; a year and a half later, I came along.

Then, because they already had two healthy children, the agency told them they wouldn’t receive priority for additional adoptions and asked whether they’d consider a hard-to-place child.

They said yes and got a phone call almost immediately. There was a baby with cystic fibrosis; did they want to see him?

“We didn’t know what CF was,” Dad told me recently. “We were told that it was serious and that Pete might not live very long. We went to visit him at the foster home, and Pete was the most charismatic little baby.” He paused. “You all were, of course, but there was just something special about Pete.”

“He had the biggest eyes,” Mom said. “He wasn’t smiling, but he looked right at you and you could tell he was happy.”

It must have seemed to Mom and Dad on that spring evening in 1981 that the warnings were coming true too fast. Peter—who had been part of our family for just a year—had an intestinal problem caused by cystic fibrosis.

If Peter had been born a few decades earlier, we might have known him only as the baby with big eyes. In the 1950s, most children born with cystic fibrosis lived just a few years before they died from digestive and respiratory problems.

But the remarkable thing about Peter’s first medical emergency— and perhaps the reason my memory of it is so vivid—is how rare such episodes were during his childhood.

Peter was growing up at a time when doctors and researchers were making big strides in treating CF, transforming it from a disease that doomed toddlers to one that affected teens and young adults.

When Peter was ten years old, scientists located the gene that causes cystic fibrosis. Within a year, they cured the disease in a petri dish.

I grew up expecting to hear any day that the cure was ready for humans. I tried not to think about what would happen if the scientists failed. Until recently, I couldn’t explain what CF was or even say with certainty how my brother dealt with his disease.

Last year I decided to find out.

Peter wasn’t a child anymore—he had a law degree and a serious girlfriend. I decided I couldn’t ignore his illness any longer.

I had never thought of Peter as a sick kid. The outward signs of his disease—the drugs, the medical equipment, his constant, rumbling cough—were so familiar that I barely noticed them.

There didn’t seem to be anything Peter wasn’t allowed to do because of cystic fibrosis. He joined the middle-school football team and, despite his tiny size, was assigned to play tight end—a fact that continues to amuse Dad.

But every now and then, I would read or hear something that knocked the wind out of me. Being reminded of CF’s harsh realities was like having one of those nightmares in which you realize the semester’s almost over and you forgot to study.

People with CF—there are 30,000 in the United States—gradually lose breathing capacity. Their airways lack a thin lining of water and thus get clogged with mucus, which invites infection, which causes inflammation, which leads to more mucus—causing slow suffocation. Lung transplants are a last resort; only half of patients survive five years after the surgery.

I remember a seventh-grade science lesson on genetics. The textbook said most people with CF died before they reached adulthood, something my parents had never told me.

My teacher interrupted whoever was reading out loud so she could elaborate on the disease’s horrors. I got up to go to the restroom, where I took deep breaths as tears streamed down my checks.

In our house, “clapping” referred to the hour each day Mom spent pounding on Peter’s back and chest to clear his airways. He had two daily 20-minute sessions of “doing his breathing”—inhaling aerosolized antibiotics through a machine that made his exhalations sound like Darth Vader’s. “Meds” were the enzymes he needed every time he ate. “Cultures” were samples of what was in his lungs.

Peter used to tell me about the “pinch doctors.” He was a pale kid with a distended stomach, and I pictured him standing in a white room encircled by scientists wielding long needles.

When I asked Mom about it this year, she said they were just drawing blood for his routine tests; they had to pinch him to find a vein in his tiny arms.

Waiting for Peter’s next checkup was the hardest part for Mom. She listened to his cough, trying to discern from the pitch and tone whether the mucus had loosened (good) or tightened (bad). She was on guard for signs of a cold or flu and tried to coax him into eating more. He subsisted primarily on Fruity Pebbles, Count Chocula, and other sugary cereals, plus hot dogs and the Fruit Roll-Ups he hoarded under his bed.

Last year I started reading about the disease and suddenly wanted to know everything. I spent days poring over medical books and journals at the Library of Congress. I filled a three-inch binder with my research.

Cystic fibrosis wasn’t identified until 1938, when a Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center pathologist published an analysis of autopsies on infants and children who had cysts and scarring on the pancreas.

In 1955, a group of parents and doctors organized the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. They opened clinics, funded research, and tracked patient outcomes. By 1981, two years after Peter was born, life expectancy hit 20 years.

When scientists found the cystic-fibrosis gene in 1989, many of those working in gene therapy—in which researchers insert modified DNA into patients’ cells—turned their attention to CF.

I remember as a teenager hearing Rosie O’Donnell, who has a nephew with CF, say on her talk show that the disease was so close to being cured.

The speaker at my high-school graduation in 1995 was a geneticist, and when I told him I hoped to join the fight against CF, he said not to bother—there would be a cure before I could finish medical school.

I started my freshman year at Georgetown as a biochemistry major but switched to English. That was 12 years ago.

Peter and I sat in his room in our parents’ Milwaukee house just before dusk on a spring evening in 2006. In Washington the cherry blossoms had already covered the sidewalks with their pink confetti, but in Wisconsin the trees were still bare.

Peter had moved back in with Mom and Dad a few days earlier, after working for nine months as an attorney in a small town. It had been a lonely winter, and he was relieved to be home.

I wanted to ask Peter all the questions I’d avoided out of fear of upsetting him or, worse, showing him how much his disease upset me: Did he dwell on his illness or try not to think about it? What had he told his girlfriend? How did people react? Did he think of himself as a sick person?

“I feel good,” Peter said. “I mean, I’m really healthy, so I don’t think about it that much.”

I asked if he’d thought there would be a cure by now.

He stared at the carpet, then looked up. “Yeah,” he said, “I guess I thought there would.”

At 28, Peter doesn’t look sick. He has ruddy cheeks, a big smile, and bright hazel eyes. He’s no linebacker, but he can launch a golf ball 300 yards down the center of a fairway.

The only sign of his illness is his cough, which makes him sound like a pack-a-day smoker.

Peter has a droll sense of humor and can be a clown. When he likes something—a sandwich from Subway or takeout Chinese—he’ll act as though it’s a gourmet meal, patting the corners of his lips with a napkin and declaring it “very fine” or “delightful.”

The joke is funnier because he’s such a picky eater.

He still loves sugary cereals, but his new food obsessions include bacon and steak.

“I can still remember the day I almost met my match—a 20 oz. filet,” he wrote in a recent e-mail. “I prevailed in the end.” Most people with CF don’t absorb much of the fat they consume, so normal diet rules don’t apply. As his doctor says, “Any calorie is a good calorie.”

Our CF vocabulary has expanded to include TOBI and Pulmozyme, the first drugs designed for his disease, and the Flutter, a kazoolike gadget that makes Peter’s airways vibrate when he exhales through it, giving Mom a permanent break from “clapping.”

I told Peter a fact I had recently learned: The amount of water he’s missing in each lung—the difference between CF and health—is less than half a teaspoon.

He raised his eyebrows, then shook his head. I could tell what he was thinking. Half a teaspoon? Why can’t they fix it?

Peter was surprised when I told him I’d arranged an interview with Robert Beall, president of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, headquartered in Bethesda. His e-mailed response—“Holy S—!”—reminded me that my family was waiting to hear what I could find out.

I wanted to know where the scientific community stood: Should I keep hoping a breakthrough would arrive in time?

Beall’s favorite prop is a multicolored bar chart he calls “the pipeline.” It shows 33 treatments in various stages of development, from basic research to market availability.

I asked him to put the chart into perspective. Are there more possibilities now than in the past?

“There are more drugs in the pipeline now than in the 50-year cumulative history of the foundation,” he said.

Beall was upbeat as he described the treatments, including a handful that would correct CF’s basic defect instead of just moderating its symptoms. He showed me headlines from articles highlighting the foundation’s success.

His manner hardened when I asked if he had expected there to be a cure by now.

“I don’t know what you’re defining as a cure,” he said. “If you mean a one-time therapy, that’s not going to happen.” Instead, there will be repeatable treatments to minimize the damage, allowing patients to live longer and better.

The cure that was supposed to be right around the corner hadn’t panned out, but according to Beall, researchers are on the cusp of several major breakthroughs. All Peter had to do was stick to his treatment regimen.

I went home again shortly after my interview with Beall, and Dad and I sat in the sunroom one morning. He wanted to hear about the meeting.

I told him how impressive the foundation seemed; it invests more in drug research than any other disease foundation in the country. I told him how many new treatments were being tested and how important it was for Peter to stay in shape so he could benefit from the new drugs. In the last four years, median CF life expectancy had risen from 32 years to 37.

“What about gene therapy?” Dad asked. “Did you get the sense that they’re close to a cure?”

As I answered, I saw a flash of vulnerability in his face. When I finished, he exhaled, squared his shoulders, and was off to work.

“Well, it’s in God’s hands”—I can’t remember whether he actually said that or if I could just tell he was silently repeating the mantra that enables him to remain unfailingly optimistic.

When I had first told Mom that I planned to research cystic fibrosis, she was wary. “You’re not going to like it,” she said.

But learning about the disease was encouraging: The researchers and other experts I spoke with echoed Beall’s optimism. Then I interviewed Peter’s doctor, Julie Biller. Peter had given her permission to talk about his condition.

“Looking at the notes here, it’s been a long time since I’ve seen him,” she said. “Pretty soon he’s going to be on the naughty list.”

CF patients are supposed to have checkups every three months; Peter hadn’t had one in more than a year. I wanted to know if he was on hypertonic saline, a treatment that Beall and others had praised, but she hadn’t seen her patient since it had come on the market.

When I asked about his health, she sounded cautious. “I have been encouraging him to increase the amount of treatment he does,” she said.

Biller’s records showed that while Peter is supposed to clear his airways with the Flutter twice a day, he uses it at most twice a week. His lung function back in March 2005 was 51 percent, lower than I had imagined.

“I thought he had a mild case of CF,” I said. “How would you characterize his condition?”

“He’s actually pretty average,” she said. But he doesn’t believe that he needs to spend two or three hours a day on treatments. “He’s a guy who views himself as healthy. There’s a part of him that knows he has CF, but it’s in a compartment.”

It seemed to me we’d all been coasting as though nothing were wrong, and now my brother had lost half of his breathing capacity.

Biller didn’t sound overly concerned, but I knew that Peter wasn’t even close to following the full treatment regimen. How could he neglect things that would help him live longer?

I thought of his time as a competitive golfer. Peter had dreaming of winning state tournaments, but he never put in the hours on the driving range. Whatever success he had came mostly through natural ability, but in the big competitions there was always someone better prepared.

His health seemed similar. Peter wanted to be well but wasn’t willing to take the necessary steps toward that goal.

In 2005, Newsweek ran an article that said, “People with cystic fibrosis now have adulthoods they could never have imagined.”

It told of a 32-year-old Minnesota man with cystic fibrosis who smoked, drank, and accumulated debt. “I didn’t expect to live,” he said, “so I figured, why not go out and enjoy every minute I can?”

Another patient, a 33-year-old mother of three from Florida, said, “I can’t remember a time when I didn’t know I was supposed to die.”

Peter never doubted he would have a future. We talked about the careers we wanted—he planned to be a lawyer like Dad or play golf on the PGA tour. We talked about what our spouses would be like, what kind of homes we’d buy, how we’d raise our kids; his would eat whatever they wanted.

Biller warned me not to come down hard on Peter. “His attitude is typical of patients who are able to lead relatively normal lives despite their illness,” she said. “He’s used to living with diminished breathing capacity and doesn’t want CF to dominate his life. A certain part of that mindset is good.”

The day after Peter and I sat in his room talking about CF, I asked if we could chat again. This time I called on my inner coach: He should see Biller because there are new treatments; he should do everything he can to fight CF for the next few years—even if he needs to spend two or three hours a day on his health—until there are drugs that will make his treatments less time-consuming.

Peter listened. I rarely appreciate unsolicited advice, so I was surprised that he seemed receptive even as I danced across the line between concern and nagging. I wondered if he felt relieved I was acknowledging his disease instead of pretending it didn’t exist.

Not that Peter agreed with everything I said. There are things he doesn’t want to do, like use a vibrating vest that shakes loose the mucus in his lungs; it makes him cough more and feel tired.

I could tell I wasn’t going to change his mind, even though one expert I’d interviewed—Richard Boucher, director of the CF center at the University of North Carolina—told me that patients adjust to the vest’s effects. The hypertonic-saline therapy—a mist of strong saltwater that one inhales—tastes bad and causes irritation. It could add years to Peter’s life, but will he think it’s worthwhile?

“If I were him, I’d do the vest and hypertonic saline simultaneously,” Boucher said. “More is better.” He told me Peter could probably get his lung function back up to 60 percent and keep it there indefinitely.

I liked Boucher’s intensity. The mantra of my college rowing team was “If it’s worth doing, it’s worth overdoing.” But Peter didn’t share this attitude.

I tried another tack. Boucher had described a new drug he’d helped develop that’s now in the last phase of clinical trials. It mimics a hormone that hydrates the lungs as the patient exercises; the drug keeps this process turned on all the time to clear mucus from CF airways. Boucher had explained that even without the drug, CF patients can hydrate their lungs through exercise, especially jogging.

“While you’re running,” I told Peter, “it’s like you don’t have CF.”

This got his attention. Peter had always assumed he couldn’t run because of his breathing problems. But we went to the store together and bought a pair of shoes.

We started out on a jog, and I coached him: Relax your arms. Run as slowly as you want. It’ll get easier over time.

It had been a rainy month, and we passed a mallard floating in a pond in our parents’ front yard. We jogged along the main road, past houses set far back from the street. Peter stopped to walk, then started again.

We reached a large park and ran across the grass to the bluff overlooking Lake Michigan. “Try to run all the way to the other end of this field,” I said. He stopped short of the goal, and we walked.

Peter had questions: How often should he run? Should his heel hit the ground first? How far should he go? I felt useful. I’d competed in marathons and triathlons and was married to a former track star. I could turn that knowledge into action; I could do something about Peter’s illness.

We returned on a runner’s high—not from a hard workout, just from the fact that Peter had been out there.

Just a month later, in May 2006, Peter ran out of Pulmozyme, a medication he needs every day. Because of an insurance glitch he went more than a week before refilling his prescription rather than pay for it out of pocket. Then he indefinitely postponed the appointment I had badgered him into making with Biller because, he said, he couldn’t get time away from his job at a large bank.

“He needs to wake up!” I yelled to my parents and sometimes to no one in particular, though not to Peter. I called his cell phone ten times until he answered. I made small talk for two minutes, then pleaded with him to make another appointment. “Promise me,” I said.

“He’s listening,” Dad said. “But you have to stick with it. You’re more effective than Mom and I.” He sounded tired.

“Keep writing,” Mom said. She was counting on this article to change Peter’s perspective, to inspire him to be more aggressive in fighting his disease.

But writing was harder than I’d expected. After finally facing the reality of Peter’s illness, it felt like torture to think about it every day. I lay in bed feeling claustrophobic as I pondered the inevitability of death—Peter’s, my own, my parents’.

That’s why I began to understand how Peter could choose not to do everything possible to improve his health. I can’t think about CF all the time, either.

When I showed a draft of this article to Dad, his secretary e-mailed me three versions with his changes and a new conclusion. He had toned down my conversation with Biller and my frustrations at Peter’s failure to follow her instructions. Dad thought I would embarrass Peter.

I understood his wanting to protect his son and worried that he was right—that my article would hurt Peter.

The next day, I called Peter to talk about what I planned to write.

“Put everything in there,” he said. “I want your article to be real.” He said he hoped his story would help parents understand that kids with CF can have full, happy lives.

“What about the fact that you don’t do all these things that would add years to your life?” I asked.

“There are lots of people with diseases who could do more. But nobody’s perfect.”

I told him how hard that was for me to accept.

“I’ve got to live my life,” he said.

“You’re good at using words good,” Peter joked by e-mail when he read what I’d written about him. Then he said what I most wanted to hear: “I want to do better on medicines. I think I will be able to.”

Peter has gone to see Biller twice in the last year. He still jogs sometimes, and he hits the gym four times a week.

He filled a prescription for hypertonic saline but used it for only a few days. “I’ve been seriously thinking about seriously thinking about doing it, though,” he wrote in an e-mail. “I need a boost.”

I wish I could give him that boost, but I don’t know how.

I’ve pleaded and coaxed so much that it’s driven both of us crazy. We’ve fallen into a pattern: He hears me out and promises to think about it. For a while, it felt like he was avoiding me during my visits to Milwaukee.

I don’t want to miss out on spending time with Peter; it’s one of the best parts of going home. I also don’t want him to see me as someone who always reminds him that he’s sick.

Peter and I sat around a campfire this past summer while on vacation in northern Wisconsin. The stars were out, and it was quiet except for the snapping fire and the loons calling on the lake.

“I was thinking about you the other day,” I said. “About how people always talk about fighting cancer or battling heart disease. That’s how they describe illness—like a war. But with you, it’s more like a compromise. You’re willing to do a certain amount each day, and in turn you expect the disease to let you have a normal life.”

“Yeah,” he said. “That’s true.” His voice had brightened, and I could tell he liked the metaphor.

“I worry it’s a false compromise,” I said, “that CF is not really in on the deal.”

Peter didn’t reply, and we both watched the flames. A motorboat sped past.

“I’m going to leave you alone about it now,” I said. “I won’t nag you anymore.”

We put out the fire and headed inside.

As we climbed the steps to the cabin our family had rented, I put my arm around him. It’s not the sort of thing I normally do, and it felt awkward.

“You’ll always be my little brother,” I said. It was a corny line, and I tried to deliver it in a half-joking way.

“Yeah,” he said. “I know.”

Denise Kersten Wills can be reached at denisekerstenwillsATgmailDOTcom.