The killing of Osama bin Laden this week by US Navy SEALs in Pakistan has raised questions about what might have happened if bin Laden had been captured alive. Would he have ended up in Guantanamo? Would he have stood trial in the United States? These questions aren't entirely new—in fact, after the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, few officials expected dictator Saddam Hussein to be taken alive. He, however, gave up meekly, crawling out of an underground hole and announcing to the US troops, "My name is Saddam Hussein. I am the president of Iraq and I want to negotiate."

In his new book The Threat Matrix: The FBI at War in the Age of Global Terror, Washingtonian editor Garrett M. Graff describes how the U.S. reacted to the capture of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein in December 2003. And in this excerpt from the April issue of The Washingtonian, he tells the incredible story of the relationship between the FBI interrogator and the Iraqi dictator that developed while he was in U.S. custody.

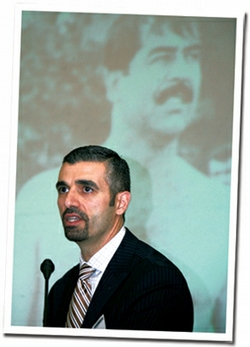

FBI agent George Piro was driving south on the Fairfax County Parkway when his cell phone rang on Christmas Eve 2003. He knew immediately it was something big: "It was my section chief—my boss's boss," Piro says. The mission was quickly explained: Just months after returning from his first wartime deployment to Iraq, he was being ordered back. He had a new assignment: to interrogate Saddam Hussein.

Piro's path to Iraq had begun two years earlier, on September 11, 2001. Then the sole Arabic speaker in the FBI's Phoenix field office, he had watched the attacks on the television in the office gym. Piro's knowledge of Islamic extremism was unparalleled in the bureau. Born in Lebanon, he and his family lived through years of the civil war there before moving to California's San Joaquin Valley when he was 12. He already had a deeper understanding of the threat of groups such as Hezbollah and Hamas than most counterterrorism experts. Drawn from the start to law enforcement—Air Force security police, then a police detective in California—he became an FBI agent in 1999.

On 9/11, the Phoenix field office had a single squad working all the various threads of international terror. Piro worked with Kenneth Williams, a more experienced agent, and they'd made some good cases in just two years, including the bureau's first prosecution of an Iranian agent for violating sanctions against Iran. In the summer of 2001, Williams, after his work with Piro, had sent FBI headquarters an "electronic communication" warning of Arab students taking flight lessons; the so-called "Phoenix memo" would be held up later as a missed opportunity before 9/11.

Starting just after 7 am in Phoenix on September 11, Piro watched the attacks unfold on TV. He quickly showered and headed upstairs to meet Williams, who had been through big cases before—he'd helped work the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Williams began to tell Piro what the coming days were likely to hold for the Phoenix office. As the attacks continued on the East Coast, the partners decided they didn't want to sit around waiting for an order. They knew Phoenix had the nation's second-highest concentration of flight schools. Piro opened the Yellow Pages and scanned the listings until he found three programs that offered commercial licenses. The two men set out.

Next: "I've Identified one of the hijackers."

Just then, Piro's cell phone rang. On the line was an agent at Boston's Logan Airport with a name from the flight manifest for the Phoenix team to check out: Hani Hanjour. I"'m holding his file in my hands right now," Piro said.

They raced back to the field office. "I've identified one of the hijackers," Piro told his squad leader.

"Get out of here—I don't have time for jokes today," his supervisor said.

Hanjour's file was just the beginning: A second hijacker also had trained nearby. And there were other suspicious individuals who hadn't been on the planes—were they lying in wait for a second wave? Warning bells went off as they examined the file of Faisal al-Salmi. He was Saudi, matched the age range of the other hijackers, had signed up for flight lessons along with Hanjour, but hadn't performed well. "If this guy ran into a cloud, he'd be dead," one flight instructor said of him.

On September 18, Piro and Williams knocked on al-Salmi's door. Over the next eight hours, the agents interrogated him, first at his apartment and then at the FBI field office.

"I was very uncomfortable with his statement," recalls Piro, who alternated between Arabic and English in his questioning. Initially al-Salmi denied any ties to Hanjour. By night's end, he admitted having had conversations with Hanjour. Al-Salmi, indicted for lying to federal agents, became the first arrest directly tied to the 9/11 investigation.

September was the beginning of a whirlwind for Piro and Williams, neither of whom took a day off until Thanksgiving—and got going again as soon as the turkey was eaten. By February, Piro was in the United Arab Emirates as the FBI's temporary legal attache tracing the money and hijackers' schedules. August found him in Amman, Jordan, running leads and investigating the assassination of US diplomat Laurence Foley, who was killed by al-Qaeda sympathizers. Then came a transfer to the Washington Fly Team, the elite FBI unit tasked with responding to terrorist incidents overseas.

In the spring of 2003, weeks after the United States invaded Iraq, Piro arrived as part of the first FBI team to help occupy the country. The 16-member team settled into a two-room shack on the edge of the Baghdad airport.

Piro had flown commercially from DC to Qatar and then on to Baghdad by "milair," the teeth-rattling military transport flights that were shuttling millions of pounds of supplies and material into the captured Iraqi capital. Wary of shoulder-fired missiles, the pilots came in high and then dove, corkscrewing in sharp turns down to the runway. "You go from staying the night before at the Ritz-Carlton in Doha to locking and loading your M4 as you hit the ground," Piro recalls. Baghdad was a shock to his senses, even though the Lebanese-American agent had lived just 500 miles away in Lebanon as a child.

For Piro and the other agents, the tasks ahead were manifold—training Iraqi police, investigating crimes of the deposed regime, searching for weapons of mass destruction, helping US forces pacify the country. The American military leadership only gradually realized how hard it was going to be.

The commander of the Joint Special Operations Command, General Stanley McChrystal, first asked for FBI agents to be embedded with the military in Iraq, thinking they could help find fugitive members of the Iraqi regime.

"We saw it as a chance to get on the battlefield and find links to the United States," says FBI agent James Davis.

The FBI had sent agents mostly drawn from the elite Hostage Rescue Team, but then it got a clarifying message from McChrystal explaining his desire for men like the street cop on NYPD Blue. "I got shooters. I appreciate that," he said. "I need Sipowicz. I need investigators. We can take care of killing people."

Next: The evolution of the FBI presence in Iraq

The next FBI wave was heavy on case agents, analysts, and evidence-collection teams' people not focused on making arrests but on ensuring actionable, evidence-based intelligence. Over the coming years, some 1,500 FBI personnel would serve in Iraq, hundreds more in Afghanistan.

Piro and the 16 members of the FBI's Iraq deployment slept in one big room and worked in the other. At night, to break up the monotony of military MREs (Meals Ready to Eat), Piro and his teammates would zip into downtown Baghdad to buy groceries, fresh-baked bread, or takeout dinners. He recalls, "That was the happy time in Iraq. Being an Arabic speaker gave me a chance to be involved in all sorts of projects." By the time Piro returned to Baghdad in early 2004, that freedom no longer existed.

During the brief period when there was some safety and a stable environment in Baghdad, the FBI ended up operating as a default police force—a very small one. The Army and Marines had little experience policing urban areas, and the Iraqi police were mostly absent. "All the investigative techniques we use on fugitives cases work the same," Piro says. "Baghdad was a large, secure metropolitan area—we had a ton of experience operating under those conditions in the US; the military didn't."

Agents helped train the Iraqi police force; worked kidnapping, money-laundering, and terrorist-financing cases; and established fingerprinting and biometric services for the occupying forces. As the FBI presence in Iraq evolved—and billions in poorly monitored money flooded into Iraq—one of the agents in Baghdad was assigned solely to investigating government corruption.

Piro's Arabic fluency was in demand, and at odd hours he received calls from the military with requests to accompany troops on missions. One night in June, he found himself helping capture Saddam Hussein's personal secretary, Abid Hamid Mahmud al-Tikriti, the highest-ranking Iraqi official caught to that point.

In another instance, as the FBI was tracking a bomb maker across Baghdad, Piro dressed as an Iraqi and was dropped off a few blocks from the suspect's apartment. He walked through the crowds, made his way into the suspect's building, and surreptitiously photographed the doors and locks in preparation for a raid. At 3 am, the military and the FBI came back in full force, just missing the suspect.

As he rotated out after his 90-day stint in mid-2003, Piro wondered whether he'd return and, if so, under what conditions.

Next: No one had expected Saddam to be taken alive.

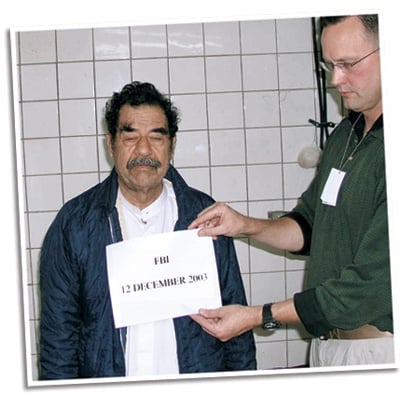

On December 13, 2003, James Davis, deputy commander of the FBI's Baghdad team, awoke to a wildfire of rumors that Saddam Hussein had been located. Such stories were common, so at first it seemed like nothing more than the usual scuttlebutt. Then Davis's boss, on-scene commander Ed Worthington, called from the US military's headquarters in the Green Zone: I can't tell you anything, but round up a fingerprint expert. "It was pretty clear to me what he's saying," Davis remembers.

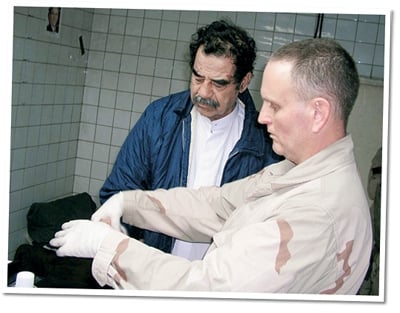

The FBI found itself taking custody of the most wanted man in Iraq. Davis held the dictator while agents took his fingerprints and mug shot (pictured below), as they would do with any other fugitive from justice. Coalition forces didn't immediately start interrogating Saddam Hussein, as the dictator was in dire physical shape following his months on the run; efforts focused first on ensuring his health. The United States couldn't afford to have him die on its watch.

Saddam was granted enemy-prisoner-of-‘war status, which meant he was protected by the Geneva Conventions against some of the "enhanced interrogation" methods the United States had used on al-Qaeda detainees. In addition to being charged with atrocities against his own citizens, Saddam was still the object of a US investigation into the foiled plot to assassinate former President George H.W. Bush in Kuwait in April 1993.

Until a special cell could be built, Saddam was held in the coalition's high-value-detainee facility known as Camp Cropper. Located near the airport, Camp Cropper had started out as the central booking facility for Iraqi prisoners and morphed into a high-profile prison for regime members such as Tariq Aziz and the man known as Chemical Ali. On one wall of Saddam's tiled cell, photos of Donald Rumsfeld and George W. Bush stood watch. On the facing wall, a poster of the US military's "deck of cards" tracked the capture of the Iraqi regime, so Saddam—the ace of spades—could watch each day as the net circled more tightly around members of his government.

No one had expected Saddam to be taken alive, so there was only the barest outline of a plan to deal with him. The CIA wanted to be the only agency to question the Iraqi leader, though it quickly allowed in the FBI when it was told that whoever questioned Saddam might later have to testify in court proceedings. Saddam Hussein, the US government decided, would be the FBI's show to run.

For days after getting the Christmas Eve call while driving on the Fairfax County Parkway, Piro spent long hours holed up at the FBI's Washington field office near Judiciary Square with an intelligence analyst developing a framework for an interrogation strategy. Piro met with other government agencies to discuss some of the topics but was mostly on his own. It was standard procedure in a way: Investigate a case. Break the suspect. Get the confession. But what was the case? And how would the suspect react?

"I was just hoping he'd talk to me,"Piro says. "I don't lack for confidence, but this guy—from a distance he's larger than life. He's brought us to two wars. He's manipulated the world stage, kept the only true superpower at bay. He was an icon. Holy crap—what am I doing?"

Piro devoured books and reports on Saddam and the Iraqi regime, building on the knowledge he'd acquired during his first rotation in Iraq the summer before. He watched Dan Rather's 2003 CBS News interview with the Iraqi leader, read reports by Human Rights Watch about atrocities committed by the regime, and paged through then-classified reports on Iraq's supposed WMD programs.

Next: Saddam wouldn't be able to communicate with anyone but Piro.

When he left Washington in January 2004, Piro was told to prepare to be gone for a year. He said an emotional goodbye to his family at Dulles International Airport. A thousand logistical challenges and questions awaited him. He had to understand Saddam's physical and psychological state, establish the interrogation setting, and prepare for months of intense interviewing.

To assist him, Piro had one other agent, two intelligence analysts, a profiler from the bureau's Behavioral Analysis Unit, and a handful of linguists. Midway through the project, the second agent—who, because of the sensitive nature of his ongoing work, hasn't been publicly named—rotated out, and Piro was asked to help select another partner. He called Todd Irinaga. While Piro was a police officer in Ceres, California, the two men had worked bank robberies and carjackings, and Irinaga had recruited Piro into the FBI in the late 1990s. Piro considered him a solid, well-rounded agent. Irinaga, then head of the FBI's Modesto office, didn't believe Piro's offer at first, but once he realized it wasn't a prank, he jumped at the chance.

While more than 100 CIA and FBI personnel were conducting interrogations in Camp Cropper, where high-value detainees were held in what came to be known as the "petting zoo," the Saddam unit was single-minded. Though its reports were shared with the CIA and other agencies, only the FBI was involved in the interrogations.

"The primary purpose was intelligence, yet we also had to be aware of his history," Piro recalls. "You couldn't ignore the atrocities that Saddam committed, and it was clear that he might face prosecution for them." The question of jurisdiction hadn't been settled—whether Saddam could face a US trial, an international trial, or an Iraqi trial. That meant that the whole team had to be able to testify in a variety of settings. Agents also interrogated other high-value detainees, such as Chemical Ali and Tariq Aziz, to gather insights into Saddam and, as Piro says, "other information that could either corroborate or contradict what Saddam was telling us."

First the team needed to take control. Because Saddam was believed to speak some English, his guards were replaced by Puerto Rican National Guard troops who were told to talk only in Spanish. Saddam wouldn't be able to communicate with anyone but Piro. "Every interaction had to be controlled," Piro says. "All of these things were imposed on him slowly, forcing him to ask me for things."

Piro had every clock removed from Saddam's view, then walked into the interrogations wearing the biggest watch he could find. "When you're in prison, robbed of all sense of time, day or night, you're desperate to know the time," he says. "I wanted him to know that it was easy for me to know the time. For him, it was impossible. It was all about establishing dominance."

While Piro had little say over what ultimately happened to Saddam, he projected a sense that he did.

Next: High Value Detainee #1

When Piro began, Saddam sat on a metal chair with his back against the far wall of the room. Piro sat in front of the door, physically between Saddam and freedom. The process was designed to keep Saddam off balance over the coming months. "If they get too comfortable, they're able to control their resistance," Piro says. Over time, as the interrogation moved into more serious topics—war crimes, atrocities, weapons of mass destruction—Piro showed the leader more deference. "We wanted to show we respected his authority," Piro says.

At the first meeting, Piro introduced himself as "George." Although the men would spend hundreds of hours together over the next seven months, the Iraqi dictator would never know Piro's full name or what his position was. Piro existed only as a shadowy US government representative. "I told him that I was taking charge of his situation. We were going to be spending a lot of time together," Piro recalls. "He said he knew what I was there for. Every part of him said he shouldn't talk to me, but he couldn't help it."

As soon as Piro began to speak, Saddam knew the agent was Lebanese and Christian—a good background for the interrogation: Lebanese in the Middle East are generally neutral, and being a Christian meant that Piro didn't have a bone in Iraq's intense Sunni/Shiite Muslim rivalry. Saddam tried to be helpful by speaking Arabic with a Lebanese accent, even as, month after month, Piro's Arabic acquired an Iraqi inflection.

"It was a historic, unique opportunity to interview Saddam," Piro says. "That feeling lasted a week. Then it became work. It was incredibly intense. Every day you had to prepare yourself to interact with these people. You had to prepare to listen to their crap. Tariq Aziz loved to name-drop—he was always talking about meeting US leaders, kings, or the pope. I was thinking, 'Dude, just stop with the name-dropping. It's not going to help you.' "

Piro's days began at 6 am. At 7 am, he and the doctor monitoring Hussein would examine the dictator. There was also a daily evening medical exam, meaning that Piro was the first and last person Saddam saw nearly every day. "We could have easily made the linguist serve in that capacity," Piro says, "but I wanted that role—I needed to have nonthreatening interactions with Saddam and be able to see all sides of him."

After the morning exam, Piro would return to his office in the CIA's camp and prepare for the day's interviews. Nearly every day, the team would interview one or another of the high-value detainees. As the lead agent, he never wrote anything down in the interrogations. His partner took notes and jotted observations.

During the interrogation of Saddam, Piro conducted only 20 formal interviews; most of their daily interactions were casual. They talked politics, history, sports, arts, the Middle East, women, and family. "For me, it was important just to get to know him," Piro says. "I wanted to be able to understand his thought processes. It was an investment for those 20 interviews."

The hundreds of pages of interview notes marked "high value detainee #1", declassified five years later, provide fascinating reading. The conversations ranged across all aspects of life in Iraq: Saddam's rise to power, the Iraqi people and culture, the Iran/Iraq War of the 1980s, the invasion of Kuwait in 1990, the power of the ruling Ba'ath Party, Iraq's relationship with its neighbors, Saddam's views of Osama bin Laden.

The men discussed war strategy and geopolitics. Piro listened to an intimate, previously untold history of Iraq offered by the man who, more than anyone else, had created the modern country. Saddam explained that he had lived in fear of US attacks; he'd used the telephone himself just twice since March 1990 and moved locations daily among a variety of settings—including his 20 palaces—to make it harder to target him.

Contrary to the beliefs of Western intelligence, Saddam claimed to have never used body doubles, feeling it was too hard to mimic another person. Perhaps of most immediate interest, Saddam told Piro that while the Iraqi regime had had some contact with Osama bin Laden, he felt the al-Qaeda leader was a fanatic and not to be trusted.

Next: "If I had such weapons, I would have used them in the fight against the United States."

The Iraqi dictator remained defiant. When Piro asked him a question and referred to him as the ex-president, Saddam interjected: "I'm not the ex-president of Iraq. I am still the president of Iraq." As Hussein felt his power slipping away in the interrogations, he threatened a hunger strike. Several times, he refused to answer questions that he felt involved Iraqi "state secrets." He blamed the 1991 Gulf War on two causes: oil and Israel.

By March 2004, it was clear to Piro and the head of the Iraq Survey Group, Charles Duelfer, that the country didn't possess active weapons-of-mass-destruction programs. Piro recalls: "As it became clear to Charles that the Iraqis didn't have WMD, it became a mission to understand why we believed they did. Why were we mistaken? What had been the intentions of the regime? What were Saddam's long-term ambitions?" They began working through the historical record, asking about specific statements, overtures, and programs to see what the regime had been trying to accomplish.

Saddam explained that it was important to national pride and national security that his neighbors believed Iraq still had weapons of mass destruction. "We destroyed them. We told you, by documents," he said to Piro in one interview. "By God, if I had such weapons, I would have used them in the fight against the United States."

Saddam's WMD bluffs were, according to Piro, "basically a calculated, deliberate effort on his part to keep Iran, whom he considered to be his biggest threat, at bay. He planned to restart the program when sanctions were lifted, which would have been in 2002 if not for 9/11."

Saddam's ego pushed him into an arrogant form of cooperation. "Let me ask a direct question," Saddam began one interview in February. "I want to ask where, from the beginning of this interview process until now, has the information been going?" Piro explained that his reports were being passed up to senior US officials, probably including President George W. Bush.

"Baghdad is moving forward without you."

"Going in, I had a very good understanding of Saddam the dictator," Piro says. "I was prepared for that Saddam. I then got to see a side of Saddam that very few people ever saw—the personal, human side. You don't expect to have someone like Saddam be, for lack of a better term, normal."

Throughout his months in prison, Saddam was desperate for news of the outside world. He asked Piro about what was happening in Iraq, how the rest of the world was changing, what Russia was up to. One day, he referred to A Tale of Two Cities, in which Charles Dickens sympathetically portrays an English prisoner in a French jail from whom news of the world is kept. Piro replied, "Over time, some things have changed; others have not."

Saddam raised topics of Western culture and literature, explaining that he'd watched many American movies to gain an understanding of the American people. The two men watched documentaries about the Iraqi regime, which Saddam protested carried a Western bias. Piro forced him to watch video of Iraq's fall to US troops and of Saddam's citizens pulling down his statue. "Iraq's the cradle of civilization, and in his mind he was the next great leader of Iraq, in the same category as great historical leaders," Piro says.

The dictator was concerned about how history would remember him. He had been offered safe passage to Saudi Arabia before the invasion if he left his position as Iraq's leader, but he had refused based on how such a move would affect his legacy.

"I hope you will be just in what history you write," the dictator told Piro. The agent replied, "Fortunately or unfortunately, I will have a major impact on your history."

Over many months, Piro worked to break Saddam's spirit. One night, as the Iraqi leader was being helicoptered to a hospital for a checkup, Piro had Saddam's blindfold removed. "I allowed him to look out, and the lights were on," he recalls. "There was traffic. And it looked like any other major metropolitan city around the world." He told Saddam, "Baghdad is moving forward without you."

The dictator kept busy scribbling, in his nearly unintelligible handwriting, poems and journals that the FBI secretly read. He tended a small flower garden during his exercise time outside, working with his bare hands because he wasn't allowed access to tools.

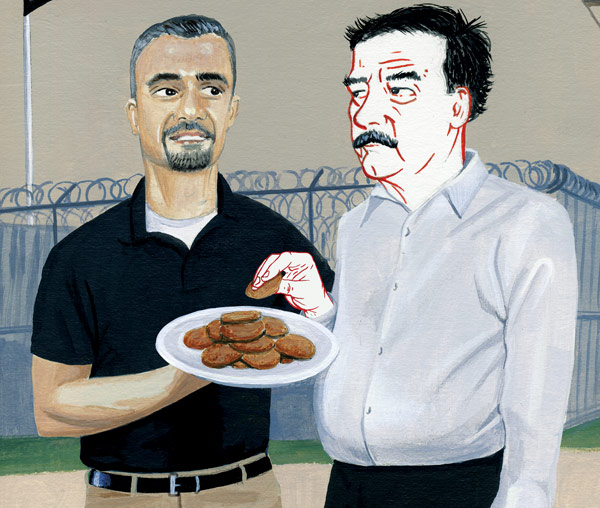

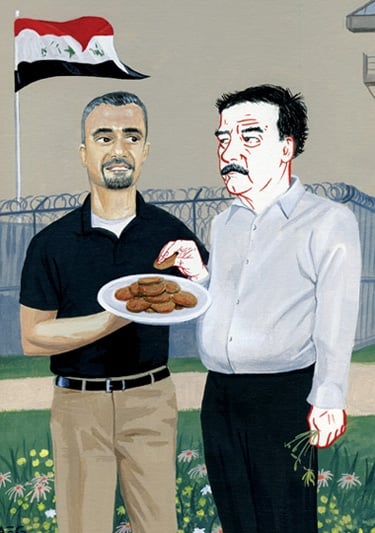

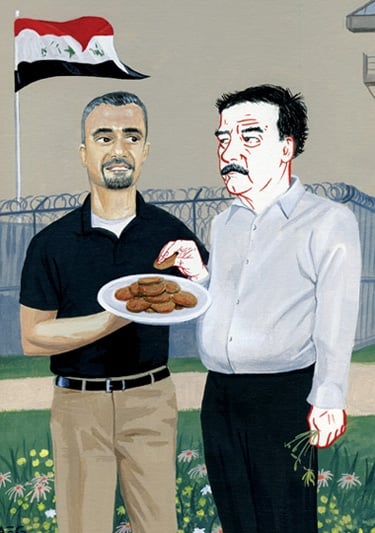

On Saddam's birthday, April 28—previously an Iraqi national holiday—only Piro noted the event, presenting the onetime ruler with a plate of traditional Lebanese cookies baked by Piro's mother in California. The Iraqi loved the cookies. Piro's mother was less pleased to find out that Saddam had been the beneficiary of her baking.

Next: Completing the first FBI interview of a foreign head of state.

The sparse surroundings meant there were few escapes for Piro. "There were two things to do—drink or work out—and I don't drink that much," he says. So every afternoon, Piro put on his MP3 player and set out through the dusty landscape of the sprawling US compound around the Baghdad airport to a soundtrack of Evanescence and Van Halen. "It was the only time I didn't have to be on—watching what I was saying, trying to interpret others— movements, reactions, and responses," he says. "I could just clear my mind." Even then, he couldn't forget where he was. Piro had to run with his handgun strapped to his waist: "You always had to be aware of your surroundings. You didn't want to be kidnapped."

Work continued until 10 pm most days and, depending on the interview schedule, sometimes as late as 3 am. The FBI team wrote weekly reports distributed to President Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, CIA director George Tenet, and other officials, yet for the most part was left alone.

In June, the interrogation process came to an abrupt end—the new Iraqi government issued an arrest warrant for the dictator, changing his status from prisoner of war to criminal fugitive and stopping the FBI interviews. "There was no room for negotiation," Piro says.

For Saddam's first court appearance, Piro procured a new suit for the deposed dictator, and an FBI intelligence analyst cut his hair. As their time together wound down, Saddam knew his end was near. On June 11, the Iraqi leader said his future was in God's hands. Piro replied that God was very busy and had more important things to deal with than Saddam or Piro. Saddam quietly agreed.

At their final meeting, the dictator teared up. Piro had brought two Cuban cigars, and the men sat in Saddam's tiny prison garden for a final chat. Then, when Piro stood to leave, Saddam wished him goodbye in the traditional Arab manner—three kisses on alternating cheeks. It was a tender gesture that left Piro feeling awkward.

"I never forgot what an evil man he was," Piro says. "As I would prepare for my interrogations, I would read over all the available intelligence and study the atrocities. They served as a daily reminder of who he was and what my task was."

Piro was happy to be done. In seven months, he'd never had a day off. Yet he'd made bureau history: completing the first FBI interview of a foreign head of state and, within the bureau, setting a record for the longest interrogation.

Looking back, Piro says he feels he obtained as much valuable intelligence information as he could, but he wishes he'd had time to ask questions of historical value.

"In hindsight, I would like to have asked more about the political landscape—Iran's role in the Middle East, Syria's role—his view of leadership, how he saw himself, his fears."

Two years later, on New Year's Eve 2006, Piro was home in Washington watching a Chicago Bears/Green Bay Packers football game on TV when news came of Saddam's execution. While the agent says he believed that Saddam deserved his fate, he didn't take any pleasure in it.

"I only watched it once," says Piro, who was appalled by the atmosphere surrounding the hanging. Iraqi officials had shouted, "Go to hell!" and chanted anti-Saddam slogans. "When the most dignified person at an execution is the person being executed," Piro says, "it does not speak well of the event."

This article first appeared in the April 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.

Subscribe to Washingtonian

Follow Washingtonian on Twitter

More>> Capital Comment Blog | News & Politics | Party Photos