When Weingarten is working on a big story, the world around him just about ceases to exist. He becomes, in his words, “the machine.” Photograph by Stephen Voss

The son asks the father why he’s not wearing a seat belt. The father says it’s because long ago the father’s sister drowned. She backed her car into a swimming pool and, because she was strapped in, was unable to free herself. Her lungs filled with water and she died. The seat belt, the very device meant to protect her, sealed her doom.

The son believes the story. Why wouldn’t he? What kind of horrible person would make up a story like that?

Gene Weingarten is not a horrible person. If anything, according to those who know him, he’s empathetic, even sweet, if also obsessive, slovenly, and slightly nuts. Maybe more than slightly. He regrets fooling his son, who only found out the truth about the dead fictional sister years later.

Weingarten told me that anecdote knowing it would end up in print. It’s the kind of story that, depending on your point of view, you might find either darkly funny or deeply repugnant. It is comedy and tragedy with a side of self-flagellation. It is Gene Weingarten, abridged.

Read Some of Weingarten’s Best Work:

You probably know Weingarten. He writes a humor column that runs in the back of the Washington Post Magazine. He helps run the Post Hunt, the paper’s annual urban-puzzle contest. Perhaps you’ve noticed his byline atop stories like the one about the famous violinist who played during morning rush hour at a Metro station and was more or less ignored. Or maybe you’ve seen the comic strip, Barney & Clyde, that he writes with his son, who didn’t let that morbid joke-gone-wrong ruin their relationship.

Weingarten may also be the best writer in American journalism. He’s the only person to have won the Pulitzer Prize for feature writing twice, once for the violinist story and once for a story about parents who accidentally leave their children in hot cars. And as amazing as those articles are, neither is generally considered his finest. That story, about a children’s entertainer, is as good a piece of writing as you’ll ever find tossed on your front lawn.

You might wonder why the best writer in American journalism would have fake poop as his Twitter icon. Or spend an inordinate amount of time making prank phone calls. Or concern himself with monkey sex, fake sneezes, or bacon taped to cats. As he once put it in a column, “I mostly write about underpants.”

Weingarten is not a horrible person, but there may be something wrong with him.

Next: “I wanted to be great at something.”

When I meet Weingarten for lunch at the Tastee Diner in Silver Spring, he shows up wearing a Bronx High School of Science hoodie. Weingarten graduated from that highly touted magnet school in 1968. He’s one of a half dozen Pulitzer winners who spent their teenage years roaming its halls. He’s not, for the record, one of the seven Nobel laureates. Weingarten describes Bronx Science, as it’s known, in this semi-fond manner: “The school was entirely filled with Jews wearing eyeglasses as thick as Sealy Posturepedic mattresses.”

He then enrolled a half hour south at New York University. He majored in psychology, but he preferred the newsroom to the classroom.

“It is possible to spend 80 hours a week editing a paper, which is what I did,” he says.

Three credits shy of that psychology degree, he abandoned higher education to hang out with Puerto Rican street gangs in the South Bronx. He freelanced a piece about the gangs to New York magazine, which put it on the cover. The story is strong and gutsy, but reading it now is like listening to Bob Dylan’s first album—enjoyable enough, but he doesn’t sound like himself yet.

With one doozie of a clip in hand, Weingarten next got a job reporting for the Albany Knickerbocker News, where he wrote about city-hall corruption for four years. In 1977, he went to Lansing to cover state government for the Detroit Free Press. Then his career took a strange turn: He accepted an editing job at the National Law Journal in New York. Why leave a daily paper to be an editor at a publication for lawyers? Because he wanted to be closer to his then girlfriend—or, in Weingarten’s words, so he could have sex on a regular basis. He ended up marrying that girlfriend, whom he refers to as “The Rib” in his columns so she can keep her identity private. They have two kids, Molly and Dan.

But that wasn’t the only reason for the switch from reporter to editor. “I felt like I was never going to be a great writer,” he says. “I felt like I was going to be a good writer at best. I wanted to be great at something.”

In 1981, he became associate editor at Tropic, the Miami Herald’s Sunday magazine. The magazine had earned a writerly reputation, but when Weingarten took over as the top editor a few years later, he worried that readers were ignoring Tropic and he wanted to “snap their heads back.” According to David Von Drehle, then a staff writer at the Herald, Tropic became “the most ambitious newspaper magazine going.”

Weingarten became an editor in part, he says, because he felt he would never be a great writer.

Von Drehle recalls Weingarten chewing ballpoint pens, paper clips, and whatever other office supplies he could gnaw into submission. “I remember him going over stories again and again,” he says. “It was scary and inspiring and instructive to fall under his spell as a young journalist because it opened your eyes to what it takes to be good.”

One of those young journalists was Marc Fisher. “He’s superficially messy,” says Fisher, a former Metro columnist who’s now a senior editor at the Post. “He’s at once frivolous and fun and on the other hand deeply serious about doing top-quality work and meaningful work with every at-bat.”

Tropic’s content mirrored its editor’s dual personality. It could be doleful one week and spit-take irreverent the next.

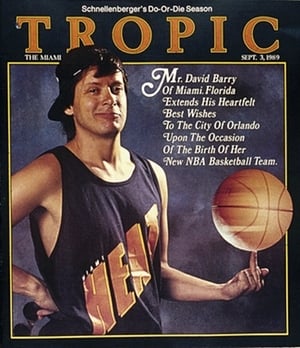

In September 1989, Weingarten and company published a cover story about the new Orlando Magic basketball team in which they mocked the city of Orlando and referred to its team’s general manager as a weenie. The article was written by Dave Barry, whom Weingarten had hired in 1984, thereby launching the career of perhaps the most famous humor columnist of the late 20th century. The article’s stated purpose was to “whip up a mindless hatred on the part of our readership in hopes of creating a classic sports rivalry.” Below a photograph of Magic cheerleaders, rather than printing their actual names, Weingarten made up monikers like Flunky, Poobles, and Spaz.

What may be most memorable about the issue is the cover photo. Pictured is Barry spinning a basketball on his middle finger. The cover line extends “heartfelt best wishes” to Orlando on the arrival of its new team.

Weingarten somehow convinced the then executive editor of the Herald that flipping the bird “isn’t really offensive to people.” Turns out it really is offensive to people, and the paper got letters, lots of letters, including one from a mother who asked what she should tell her son when he asked why his hero, the great Dave Barry, was making an obscene gesture on the cover of a magazine. The executive editor later said running the photo was the only decision she ever regretted.

Another up-and-coming writer on that staff was Joel Achenbach, who later also made the leap to the Post. One day in Miami, Achenbach turned to Weingarten and said, “We will never have better jobs than this.” More than two decades later, Weingarten says he can’t disagree.

But Weingarten then quit that dream gig over a staple. The Herald management told him it was planning to stop stapling the magazine and start printing it on lesser-quality paper. Weingarten said if they did that he would resign. When management made good on its threat, Weingarten made good on his. “I had to leave or I had no credibility for the rest of my life,” he says, “at least in my own mind.”

So in 1990 he wrote to the Washington Post and asked for a job. Mary Hadar, then the assistant managing editor for Style, got the letter. She knew Tropic because her parents lived in Fort Lauderdale and she read it when she visited. And she was a fan of the magazine—enough of one to tell Weingarten that if the Post didn’t hire him, she would jump out a window to create a slot.

The Post hired Weingarten.

Next: Witty and neurotic on page and in person

Weingarten and his wife, a lawyer, have two kids, who are now grown. Photograph of family by Michele McDonald, courtesy of Gene Weingarten

Weingarten in person is a lot like Weingarten on the page—witty, inquisitive, neurotic. The only difference I notice is that his language is saltier in conversation, though if you follow him on Twitter you’ve already had a taste of Weingarten uncensored. For instance, he called Buzz Bissinger—author of Friday Night Lights and, more recently, a goofily bellicose Tweeter—a “pussy.”

Bissinger replied by tweeting that Weingarten laughs at his own jokes and bears an uncanny resemblance to bow-tied film critic Gene Shalit, two assertions I don’t think anyone, including Weingarten, would dispute.

It took several months of e-mails to get Weingarten to sit for an interview. His hesitation is understandable. Why let someone do a job you could do better yourself? And it’s a job he’s already doing. There are autobiographical morsels strewn throughout his many columns and online chats. He’s written about his father’s failing health and his daughter’s departure for college. He’s written about a long-ago flirtation with heroin. He’s revealed that he suffers from a mild form of prosopagnosia, a condition that makes it hard if not impossible to recognize faces. He recently admitted in a column that he’s extremely freaked out when people rub their palms against fabric.

At a certain point, there’s nothing left to divulge.

The man wrote an entire book about his own hypochondria. He had trouble selling the proposal at first. Then publishers learned that he had hepatitis C and probably had five years left. The notion of a funny book by a person facing imminent demise was appealing to the suits at Simon & Schuster. He writes in the book that “there is a pretty good chance that I will be dead before you will.” The book ends by scolding readers for expecting him to send a message back once he arrives in the hereafter. “What are you—stupid? I’ll be dead.”

That was more than a dozen years ago, and Weingarten is now disease-free, or at least free of that specific disease.

He used his grim prognosis not only to get a book published but also to finagle a better position at the Post. His request to be put in charge of the Sunday Style section in the early ’90s was granted. (“Who could say no to a dying man?” he says.) That move was about trying to create a mini-Tropic within the pages of the Post, and he mostly succeeded, founding the Style Invitational, a humor contest that still maintains the silly/smart DNA of Weingarten’s time at Tropic.

In the late ’90s, he transmogrified from editor back to writer. He had stopped being a writer because he thought he would never be a great one. All those years of fixing other people’s copy had made him a student of narrative assembly. He had developed theories, including a grand philosophy of storytelling. All good stories, Weingarten had come to believe, are about the meaning of life.

In his introduction to his collection, The Fiddler in the Subway, Weingarten writes that a feature story “will never be better than pedestrian unless it can use the subject at hand to address a more universal truth.” Those universal truths always come around to a favorite maxim of Weingarten’s, one that he cribbed from fellow neurotic Franz Kafka: “The meaning of life is that it ends.”

I called a bunch of Weingarten aficionados. Most are people who have worked with him; a few have followed his career from afar. I asked each to name his or her favorite Weingarten story.

Ben Montgomery is more an admirer than a buddy of Weingarten’s. An enterprise reporter for the St. Petersburg Times, Montgomery runs Gangrey.com, a Web site whose tongue-in-cheek tagline is “prolonging the slow death of newspapers.” It’s where practitioners of narrative journalism debate their craft. Whenever Montgomery reads Weingarten’s stories, he’s overcome by feelings of inadequacy. “Because his best stuff—I know I’ll never do that,” he says. “It’s paralyzing.”

The story he names as his favorite is “Tears for Audrey,” about a mother whose three-year-old daughter is left in a vegetative state after nearly drowning in a back-yard swimming pool. The mother, who is Catholic, believes that God is causing miracles to happen because of her daughter, that her daughter is a “victim soul” who can absorb the pain and sickness of the faithful. The most tangible proof is the curious fact that oil flows from the religious figurines in her daughter’s room. Believers make pilgrimages to witness the dripping oil and to gaze upon her unresponsive daughter.

If you’re a skeptic, you want Weingarten to uncover the hoax. He doesn’t. What he does instead is persuade you to empathize with the mother. You never learn what Weingarten actually thinks. If you know he’s an atheist who once said in an online chat that he’d made a chart titled “Mathematical Proof That the Likelihood of a Deity and/or Other Supernatural Explanations for Life and/or Afterlife Declines to a Probability Approaching Zero,” then you know he probably doesn’t think Jesus is making liquids dribble from curios. But he doesn’t say that in the story. What he says is “Linda Santo has defied conventional wisdom and kept her child alive through heroic love. . . . It’s a miracle, says the Washington Post.”

Madeleine Blais, who worked with Weingarten at Tropic and is now a professor of journalism at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, says her favorite Weingarten piece is “The Ghost of the Hardy Boys.” It’s an unusual choice because it’s not one of Weingarten’s scene-driven, exhaustively reported tours de force. It’s an essay about Leslie McFarlane, the ghostwriter of the Hardy Boys series of children’s books. Really, though, it’s about worthy versus lousy writing and about the compromises you make in life, the dreams you give up to get by.

“Sometimes,” Weingarten writes, “homely things are done for the best reasons in the world, and thus achieve a beauty of their own.”

Next: Weingarten’s toxic workspace

I mention those two stories because they’re exceptions. Almost everybody I ask names the 2006 article on the Great Zucchini.

It’s not an immediately promising premise. The story is about a local children’s entertainer who is successful but disheveled. Forgettable fluff? Weingarten acknowledges as much in the story by including a conversation he had with a woman at one of the Great Zucchini’s shows. “You’re writing a story about him?” she says. “I mean, are you that desperate?”

She wants to know if there’s a hook. Weingarten assures her, and readers, that there is but that “it’s going to take some time” for the hook to be revealed. As the story unspools, we learn that the Great Zucchini, also known as Eric Knaus, is a troubled genius, a man with a nearly magical ability to connect with children, but also a man who is, by most adult standards, a complete mess. He earns six figures but has no idea where the money goes. His apartment is a wreck—the only food he has is a jumbo box of raisin bran. He’s afraid of commitment. His driver’s license has been suspended. All his appointments are in one book that, if lost, would likely ruin his career.

Weingarten writes: “I’ve known other men who approach Eric’s level of dysfunction, including myself.”

That last line is included casually, but it’s a confession. Weingarten sees himself in the Great Zucchini even though the Great Zucchini is barely able to cope with day-to-day life. And the more you know about Weingarten, the more that comparison makes sense.

Tom Shroder, Weingarten’s close friend and the former editor of the Washington Post Magazine, tells the story of when he met Weingarten back in the ’80s and had to scoop trash out of Weingarten’s car in order to sit down. He also remembers when Post employees had to move Weingarten’s desk to a different floor. When the workers saw the state it was in, with teetering piles of ratty notebooks and chewed-up pens, according to Shroder, they refused. The word “toxic” was used more than once.

Weingarten worries that he’s not funny. He once wrote, in reference to Dave Barry, “I simply do what he does, only worse.”

During our lunch, Weingarten keeps tearing off little pieces of his dirty napkin, balling them up with his thumb and forefinger, and dropping them onto his plate amid the mashed remains of his mostly eaten lunch. It’s gross.

“Have you noticed what I’m doing as I’m talking?” he says, gesturing toward the mess. “Who does this? And I’m doing it as I’m telling you that I’m neurotic!” He then points to my pad of paper and says, “If I were writing this, I would note that.”

When Weingarten is reporting a story, according to everyone, he’s focused on that and nothing else. He ceases to be a human being—he becomes, in his own words, “the machine.” He hoovers up information and that’s it. Maybe he sleeps. Maybe he eats a sandwich. But mostly he does what he does until it’s done.

“He’s worthless when he’s reporting a story,” says Shroder, who considers Weingarten “hugely intelligent and hugely insane.”

Dave Barry writes the following in his introduction to Weingarten’s book The Hypochondriac’s Guide to Life. And Death: “Ask the many people who know and love Gene Weingarten if they think he is sane, and they will say, laughingly: ‘No!’ And then, after reflecting for a moment, they will say, seriously: ‘No.’ ”

So the messy, crazy, brilliant reporter profiles the messy, crazy, brilliant children’s entertainer. It turns out to be a weirdly ideal marriage of writer and subject.

Von Drehle, now an editor-at-large for Time, is the one who gave Weingarten the tip that led to the story. He had hired the Great Zucchini for a party and suspected the guy had issues. He didn’t know much more than that, but somehow it seemed like a Weingarten piece in the making. Like a lot of people I talked to, Von Drehle thinks Zucchini should have won a Pulitzer.

I’ve read the Great Zucchini piece ten times. Maybe more. But I’m at a loss when I try to explain why it works so well. There are awesome details, such as the fact that the Great Zucchini keeps his father’s ashes in a shoebox on the floor of his closet. There’s a road trip to Atlantic City, where the Great Zucchini gambles all night. There are startling scenes, including the conversation Weingarten has with the Great Zucchini’s mother about the death of the baby across the hall.

The sentences are pitch-perfect but not flashy enough to excerpt. Washington Post writer Hank Stuever refers to Weingarten’s writing as “almost devoid of lyricism,” a comment meant as a compliment. Each section of the article feels like a chapter in a novella. It’s about comedy, kind of. It’s about parenting, in a way. It’s about the lifelong reverberations of childhood trauma. It’s about forgetting to grow up.

But none of that captures it.

In the final scene, a little girl approaches the Great Zucchini and sticks out her finger, and the Great Zucchini grabs it. “Something indefinable passes between them,” Weingarten writes. Maybe the same can be said about what passes between the writer and the reader.

Next: The story that made his readers cry

Weingarten’s first Pulitzer-winning story was titled “Pearls Before Breakfast” when it ran in the Post and was renamed “The Fiddler in the Subway” for his collection. According to Weingarten, the story got “the largest and most global response of anything I have ever written.” Some people really loved it. Other people really did not.

Charles Pierce is one of those other people. In a comment on Gangrey.com, Pierce said he hated that story “with the hate of a thousand white-hot suns.” Pierce is a longtime magazine writer and author of the bestseller Idiot America. When I call him to find out why he needed that much solar power to express his dislike of the story, he demurs. Then he changes his mind, calls me back, and says he didn’t like it because it was “classist” and that it wasn’t surprising that people had to hurry to work during morning rush hour. The story “didn’t say anything about anything,” according to Pierce.

Some commenters said the story was “pretentious,” “condescending,” and a “waste of space.” Another complaint was that having a classical musician play in a Metro station seemed contrived, a cheap stunt.

But what’s most striking about the response from readers, if you scroll through the online chat the Post conducted after the story was published, is the number of people who said it made them cry. How many newspaper stories do that?

Journalism is going through a transition. People who worry about such things worry especially about the survival of long-form journalism—the sort of stuff Gene Weingarten is known for.

In the Washington Post Magazine, where most of Weingarten’s best writing has appeared, the length of stories has been slashed. A Post editor told me that the Great Zucchini piece wouldn’t be published today, at least not at the length it ran. In 2009, a story by a freelancer about a quadruple amputee was killed, allegedly because Katharine Weymouth, the Post’s publisher, said she wanted happy stories, not depressing ones. I’m guessing Weingarten’s 2005 piece about the epidemic of suicides on a tiny island off the coast of Alaska would be deemed insufficiently cheery.

Also, the kind of journalism Weingarten does—the kind that takes months to report—is expensive. And many newspapers currently have what might be described as cash-flow issues.

But there are new outlets and financial models for long-form journalism, some of which, like Kindle Singles and Byliner, charge by the article. Plus there are Web sites, such as Longform.org, that serve as clearinghouses for exceptional nonfiction. The doomsayers may be too quick to assume that the journalism of the future will be produced solely in 140-character snippets.

Weingarten technically retired from the Post in June 2009, staying on contract to write his humor column, and he doesn’t plan on writing any more long features—though he doesn’t entirely rule it out. Perhaps after two Pulitzers he doesn’t have anything else to prove. Then again, after two Pulitzers, you’d think Post management would be beseeching him to whip out his notebook and try for the three-peat.

Weingarten does have some projects cooking, including a film script he describes as a “dark, dark comedy based on something that happened 40 years ago,” cowritten with David Simon, creator of The Wire, the HBO series that some consider the best television show ever. Tom Shroder, his buddy and editor, would like to see Weingarten return to narrative nonfiction, though not necessarily for the Post.

“I think he has a masterpiece book in him,” says Shroder, though he also wonders whether, considering Weingarten’s manic reporting-and-writing process, churning out his opus might kill him.

Most Weingarten fans say his finest story is a 2006 piece about a children’s entertainer. It’s a weirdly ideal marriage of writer and subject.

Weingarten is best known for his humor column, but he’s most praised for his feature writing. I didn’t find people who doubted Weingarten’s chops as a feature writer—even those who complain about a particular story are quick to add that he’s an excellent writer.

The humor column has lots of fans. But some readers hate it. An undiplomatic friend of mine who knew I was working on this article wondered: “Are you going to ask him why his column isn’t funny?”

Weingarten worries that he’s not funny. I don’t think he admits that to sound humble. I think he really worries about it. When he sends ideas to Shroder, who still edits the column, Shroder sometimes shoots them down. I happened across a comment Weingarten left for a random blogger who complained that he was funnier in a radio interview than he is in his weekly column. “I’ll happily admit to being old and unfunny,” Weingarten shrugged to the blogger, though I bet the “happily” was a lie.

Weingarten once wrote, in reference to Dave Barry, “I simply do what he does, only worse.” That, of course, is part of the challenge: He followed Dave freakin’ Barry, whose column used to run in the Post and everywhere else. And no one understands that fact better than Weingarten, who recognized Barry’s talent before the rest of the country, based on a guest column Barry wrote for the Philadelphia Inquirer. Weingarten is responsible for advancing the career of the legendary humorist whose shadow he’s still under.

I asked everyone I interviewed to explain the connection between Weingarten the writer of long, thoughtful, moving stories and Weingarten the writer of absurd, often scatological humor pieces. I didn’t get any decent answers. Except from Hank Stuever.

“He’s interested in human beings,” Stuever says. “Visible panty lines, farts, turds—all of that is desperately human. It’s horrifying, but it’s interesting. It’s gross, but it’s interesting.”

Weingarten himself doesn’t see comedy and tragedy as all that different, and so to him the link between the column and the stories seems obvious: “The world is nuts and you can either laugh or you can cry about it.” Besides, he says, it would be too depressing to write only about children mistakenly left to die in the back seats of cars, a reference to the Pulitzer-winning “Fatal Distraction,” a story that hurt to read and must have hurt much more to report.

Next: Acting in a ethically questionable manner

Weingarten is the only person who has twice won the Pulitzer Prize for feature writing. Photograph courtesy of the Pulitzer Prizes

I traveled to Dallas this summer to hear Weingarten speak at the Mayborn Literary Nonfiction Conference, one of those events where journalists gather to commiserate, encourage, and envy.

Weingarten had told organizers he wanted to do a Q&A session rather than give a speech. But he changed his mind, e-mailing the Mayborn folks a few days before that he had something to say after all. What he did was tell two stories, both of them about times when he’d acted in an ethically questionable manner.

The first instance occurred in 2004 when he was reporting the article “None of the Above.” In that story, Weingarten locates a guy who never votes and tries to figure out why. When he pitched the story, Post higher-ups wanted to do a survey-based, big-picture investigation. Weingarten wanted to write about one person. He prefers the microcosm.

After he spent two days with the nonvoter he chose to follow, the story wasn’t working out. Not a bust, but not a barnburner either. So he’s standing around with the nonvoter and the nonvoter’s friends when somebody pulls out a marijuana pipe. The nonvoter lights it and passes it to Weingarten.

“I was not at that point in my life taking drugs,” Weingarten tells the conference audience, “but I had in the past—no more so than your average touring funk reggae band.”

He knows that taking the pipe would violate Post policy, that he might even be fired. But he believes that turning it down would brand him as an outsider and end whatever chance he has of establishing a rapport with the nonvoter in whom he has already invested a lot of time and energy.

He takes the pipe. He smokes the pot. He gets the story—a portrait of a guy who has “willed himself into a certain protective ignorance about the way life works.”

But he doesn’t tell the Post what he’s done. He waits until years later, just before the Mayborn speech, to call Leonard Downie, former executive editor of the Post. Downie doesn’t say for sure what he would have done if he’d known at the time, but dismissal would apparently not have been out of the question.

In the second instance, Weingarten is a 23-year-old reporter working for the Albany Knickerbocker News. There’s a bribery scandal brewing, and the businessman at the center of an allegation is in the hospital. The man is ill, probably not long for this world. During the official investigation of the possible bribery, a notebook emerged with the names of city officials alongside cryptic markings. What do the markings mean?

Weingarten goes to the hospital room of the sick, perhaps crooked businessman. The man is only semi-lucid. Weingarten gets him to reveal that the markings are actually an old retailer’s code. Officials have been bribed. The paper runs a front-page story about breaking the code—Weingarten’s first big scoop.

The kicker is that, before Weingarten introduced himself, the semi-lucid man said “Doctor?” and Weingarten—rather than saying, “I’m a reporter, not your doctor”—walked over and took the man’s pulse. He did identify himself as a reporter after that, though whether the man ever understood whom he was talking to remained uncertain.

Driving home after that speech, I wondered why Weingarten chose to tell these two stories. They were funny, but some people might get the wrong idea. And some people did: There was a mini-furor among news-media types, including this from a Dallas Morning News editorial writer: “So two-time Pulitzer winner Gene Weingarten thinks it might sometimes be OK to violate those pesky ethics if it means getting a good story.”

That’s an unfair summary of Weingarten’s talk from someone who wasn’t there. For his part, Weingarten offered a vigorous defense of his actions, except for taking the guy’s pulse. That, he says, was without a doubt the most unethical thing he ever did.

But why go there? Why risk besmirching your own reputation? My theory is that this is consistent with his tendency toward self-flagellation. He reveals his faults in his columns. He writes stories about people whose mistakes and quirks mirror his own. So it makes sense that when he gives a speech in front of admiring journalists, he admits to bending the rules. It seems like a meaningful trend to me, perhaps even a profound insight.

I test this theory out on Weingarten. He doesn’t buy it. He was, he says, just trying to entertain the audience.

This article appears in the December 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.