Washington drivers spend more than twice the national average time in bumper-to-bumper traffic. Aerial Photograph by Cameron Davidson for the Washingtonian

Last August, a 911 operator took a desperate early-morning call. A man, on the way to Washington Hospital Center with his pregnant daughter, was trapped on DC’s New York Avenue by a complete traffic lockup following a fatal collision between a tractor-trailer and a dirt bike. “My daughter is having a baby!” the man shouted. The operator tried in vain to direct the gridlocked minivan to a fire station. By the time emergency crews reached the vehicle, working their way through the obstacle course of idled cars, the baby had been born in the passenger seat.

Mother and newborn daughter turned out to be fine. But surviving the great roulette wheel that’s set spinning every day by the Washington traffic Fates can be a soul-sapping experience for anyone. With painful frequency, drivers are cast into the First Circle of Hell, which is where those who have committed the sin of hoping they’ll journey uncontested spend what seems like an eternity. It can happen for no discernible reason. It can happen when someone texting clips another car. It can happen when there’s an act of God, such as last year’s Snowmageddon or August’s “just reminding you the East Coast has tectonic plates, too” earthquake.

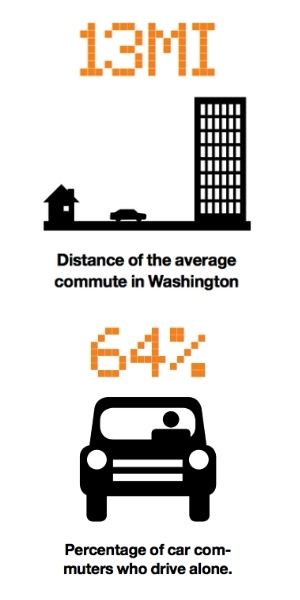

The reason is simple: There are way too many cars on the roads. There are a zillion unsurprising reasons this is true—a growing population, too many car commuters (64 percent of them solo), too many jobs located where workers don’t live (more people in Virginia and Maryland commute to work in another county than residents of any other place in the country), a lack of long-range planning and coordination among the local governments involved, and inadequate transit options, to name just a few. Or, as Dorn McGrath Jr.—professor emeritus of geography and urban and regional planning at George Washington University and a longtime denizen of the area’s transportation planning wars—sums it up: “It is pure foolishness aggravated by governmental fragmentation and, occasionally, political indifference.”

As a result, Washington has been elevated to a dubious status: a regular presence at the top of national traffic-congestion rankings. Telling drivers this is like telling a person standing in a downpour that weather statistics indicate the area is prone to rain. But the ugly numbers are worth a quick review.

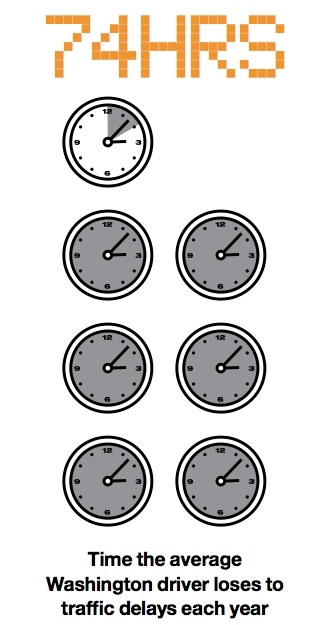

In September, Washington topped the charts—yep, numero uno—in the 2011 Texas Transportation Institute Urban Mobility Report. The data showed that the average Washington driver loses 74 hours a year to traffic congestion (in 1982, Washingtonians were delayed only 20 hours a year). That’s almost two work weeks vaporized behind the wheel, a waste that costs us an average of almost $1,500 a year in fuel and lost earnings potential. It also means that the time we spend in bumper-to-bumper conditions is more than twice the national average. Those whiny Los Angeles drivers who always think they have it the worst? They lose a mere 64 hours a year to traffic delays.

The misery of watching life slip away while parked on the Beltway has predictable society-fraying effects. In the past five years, the number of Washington drivers who say they frequently feel uncontrollable anger toward other drivers has doubled. It’s not that hard to imagine we’re heading for a post-apocalyptic nightmare involving, say, a mass brawl of unhinged federal workers on I-95 South in Virginia, the most congested stretch of road in the region and a place that, according to the Texas Transportation Institute, transforms a 23-minute commute into an 86-minute rush-hour death crawl.

Next: Ron Kirby is the man who can see our traffic future

Given the level of pain that congestion is inflicting on drivers, it seems reasonable to ask what’s being done about it. Luckily, tucked away in a bland and quiet office on 777 North Capitol Street in DC is a man who can actually see the future. He’s a mild-mannered, middle-aged, Australian transplant with a number cruncher’s assured demeanor and a soft voice that carries vestiges of his native twang. His name is Ron Kirby, and he’s director of the Department of Transportation Planning at the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments.

COG, as it’s known, was created more than 50 years ago to develop coherent planning for Maryland, Virginia, and DC. A lot of COG’s work involves the 16,000 miles of roads and transit networks that crisscross state and city lines in a complex jurisdictional web that partly explains why traffic is such a mess. Kirby is the guy whose job it is to try to sort all that out, and he spends much of his time immersed in transportation data, analysis, and projections. To the extent that anyone knows what traffic in Washington will look like in coming decades, he seems to be the guy.

Kirby meets me in the COG reception area, where I’m perusing earnest brochures with titles like “Commuter Connections (A Smarter Way to Work)” and “Region Forward (Our Region. Our Choice).” I’ve already armed myself with a decent-size cup of COG coffee, and we make our way to a conference room.

Kirby started his journey toward traffic-guru status as a PhD who built mathematical models to forecast traffic. He’s been at COG since 1987. He’s guided by numbers and rationality yet somehow maintains his equanimity in the face of local politics and planning that are often oblivious or maybe even hostile to the sensible strategies his carefully calibrated models spit out.

“The biggest issue we are facing is a total refusal to raise the gas tax,” he says, pointing out that in addition to providing funding for road and public-transit improvements, it would help spur energy efficiency and reduce our reliance on foreign oil. But local congestion isn’t just a funding problem. “Building without restraint of use is hopeless,” Kirby says, alluding to the need to get cars off the roads. “Instead of four lanes of gridlock, you end up with six.”

I ask Kirby what The Plan is. He starts to summarize a strategy for the region, known as the Financially Constrained Long-Range Plan (CLRP in COG-ese). The CLRP looks at the next 30 years and lays out what we can expect if current plans and budgets continue. It includes all the major projects expected to be built over that period, such as the Dulles Rail line, Maryland’s Purple Line, and the Intercounty Connector, which top a long list of transportation upgrades. The “financially constrained” part means that if a project or transportation idea—no matter how worthy—is unfunded, it doesn’t get included. So the CLRP is a good snapshot of how Maryland, Virginia, DC, and the federal government plan to respond to the transport needs of our region.

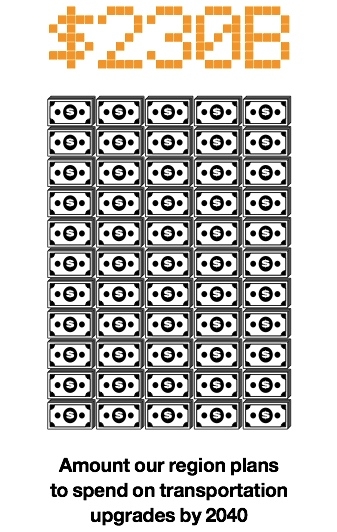

Kirby runs through the details. The amount of money spent in the CLRP scenario (from federal, state, and local sources) is far from negligible: $5.4 billion a year on average over the next 29 years, or a total of $229.9 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars, for transit, roads, and highways as well as maintenance and operations. That sounds like a lot of transpo-bang. And the CLRP numbers indicate that by 2040 the average Washingtonian will be driving a little less (4 percent), partly because more people will be using public transit to get to work (and partly because they hate the traffic).

There’s a big hitch, though. Thanks to the region’s resilient economy, its population is expected to increase by 30 percent by 2040. That’s another 1.65 million people on top of the 2010 population of 5.5 million. So even if each person drives a little less, there will still be a lot more vehicles on the roads. The result is that congestion will get a lot worse. In fact, Kirby and his team expect that by 2030 the number of hours commuters lose to traffic delays will increase by 20 percent.

“So the net result of existing plans to spend more than $200 billion,” I say to Kirby, just to be sure I have it right, “is a major increase in congestion?” He nods.

The numbers are the numbers, and I guess staying neutral about them is the only way to stay sane in his job.

Next: What is the Aspirations Scenario?

As I absorb this, Kirby throws me a little hope. “There is another scenario,” he says, no doubt eager to wipe the perturbed look off my face. “We call it the Aspirations Scenario.”

This scenario, he says, is what might be achieved if some additional elements—all of which might be considered “within reach”—are layered onto the CLRP. In other words, Kirby is about to explain what would happen to congestion with additional funding, a little political courage, and some common sense.

The CLRP Aspirations (or is it desperation?) Scenario sounds promising. The first component is for state and local governments to be smarter about land use and to create rules and incentives that concentrate growth in communities that mix residential and business zones and are located near existing or planned mass-transit centers. COG has identified 58 locations throughout the region where people do business or live—in some cases both—and the idea is to transform them into livable, workable, walkable, bikable communities that have easy access to public transportation.

This isn’t a new idea, but changing patterns of land use is hard. “We started in the 1960s with a highway-oriented policy and encouraged suburban development,” Kirby says. “Then we shifted to emphasizing transit instead of highways, but suburban growth has continued and highway capacity hasn’t.” Even if local governments, zoning boards, and developers would do the right thing on land use, it’s not a silver bullet. “Eighty-five percent of what will be on the ground in 2040 is already there or approved,” Kirby says. “Only 15 percent could change.”

Happily, the Aspirations Scenario has two more bullets. One is perhaps more radioactive than silver, but it could transform the way we drive: using E-ZPass transponders on cars to charge variable tolls for access to congestion-free lanes. High-occupancy vehicles travel free in the lanes, while low-occupancy vehicles (fewer than three people—which is the way most Americans, including Washington drivers, tend to roll) would have to pay for access to the lanes if they want to enjoy the peace and quiet of a nearly empty car.

The idea is simple and powerful. We have too many drivers competing for limited road space. If drivers had to pay for that commodity, and pay a premium for traveling at peak times, they would be more likely to carpool, take mass transit, telecommute, bike, or walk. Demand would go down. Congestion on key roads would be reduced. Traffic would start to flow again. Put aside the howls of driver outrage for a minute. The theory is already being proved in places such as London, which imposes a congestion fee on cars traveling into central parts of the city and has reduced congestion by about 30 percent.

And consider the beauty of opening up a major new revenue source, which could help pay for the aspirations plan’s third bullet: the creation of a 500-mile bus rapid-transit system that would flow along the less congested roadways and give everyone a good transportation alternative to cars.

It should be noted that the non-aspirational CLRP takes a very tentative step into the scary new world of priced lanes. It takes some 150 miles of highway and either transforms high-occupancy-vehicle (HOV) lanes into high-occupancy-toll (HOT) lanes (you travel free if you’re high occupancy or pay to use the lane if you’re not) or simply adds a HOT-lane option to the existing roadway. Drivers who carpool would be rewarded with a free, or reduced-price, fast lane, and low-occupancy drivers would have the option of paying for access to a faster lane or twiddling their thumbs and smartphones from the slow lane for free.

It’s a bit haphazard, with most of the HOT action taking place on a section of the Beltway west of DC and on 95 South. The segment of 395 between the Beltway and the Potomac River has been dropped from the plan thanks to objections from Arlington. That just happens to be one of the most congested routes in the area, and it will only get worse as 6,400 workers are dumped into the mix at a new office complex on 395 called the Mark Center, courtesy of the Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission, which is reducing the number of military bases in the area and consolidating their workforce.

Next: Traffic congestion will still get worse

The reason the CLRP is so underwhelming when it comes to priced lanes is—naturally—a reluctance to make drivers angry (even though they’re already angry about the congestion). So HOT lanes are being built only where they can either be converted from HOV lanes or added to the existing roadway without taking away free lanes. In other words, no carpool-averse driver will lose the option of enjoying the bumper-to-bumper experience in a free lane.

By contrast, the Aspirations Scenario would create a 1,650-mile network of priced lanes. Now we’re deep into Kirby’s “if only” world. You can sense how happy it would make him if the region would take such a bold and transformative step. To get to that big number, you’d start with the 150 miles of HOT lanes already planned; layer on an additional 350 miles of lanes converted from HOV; stripe in 650 miles of new, priced lanes; and convert 500 miles of “general purpose” (that is, free) lanes in the District and on national parkways. The political grenade is that this plan would take over lots of miles of free roadway. Other than that, the technology and planning are all teed up. “If the political decision could be made, this could be done,” Kirby says.

It’s bold. It’s big. It’s brave. I’m excited. “So what impact would this scenario have on congestion?” I ask.

“It would be major,” Kirby says. According to his models, by 2030 this trifecta of strategies would deliver a 6.1-percent increase in average speeds, a 13.8-percent decrease in rush-hour traffic delays for the average commuter, and a savings for commuters of about $200 a year in time.

That sounds impressive. But perhaps the COG coffee is doing its job. My brain slowly starts to process the fact that these are improvements over what the lame old CLRP will deliver, which is to say improvements compared with a dramatically deteriorating traffic picture. If instead you compare the impact the Aspirations Scenario would have with the conditions that actually exist today, suddenly it doesn’t look like something to aspire to. In fact, the hours of delay the average rush-hour commuter loses to congestion would go up by about 3 percent over today. Which means that the Aspirations Scenario—the best Kirby believes we can hope for—achieves the following: Traffic congestion will still get worse; it just won’t get orders-of-magnitude worse.

Awesome.

It’s 5:40 am on a summer Monday, and the traffic on the inner loop of the Beltway near Connecticut Avenue is in the early stages of its slow congeal toward rush-hour stasis. Summer is usually a time of lighter traffic, but cars and trucks on the racetrack curves near I-270 are already betraying a skittish urgency. Drivers, most of them alone, are veering from lane to lane in search of open road, and every exit that rolls past dumps a stream of new vehicles into the mix. You can almost feel the stress rising.

A black Ford Expedition pulls up within about six inches from my bumper, its driver jabbering on a cell phone as he waits for me to pay tribute to his vehicular mass and move out of the way. I don’t mind, because I don’t have to deal with this every day. Plus I’m on my way to Metro Networks, which has a hardened team of traffic reporters who feed traffic news to radio and TV stations throughout the Mid-Atlantic. In about 20 minutes, maybe I’ll get to watch as the Expedition’s battering-ram progress across Maryland is slammed to a stop by a full-on snarl.

Metro Networks scans the region’s roads from a bland corporate aerie on the 15th floor of an office building in Silver Spring. I’m greeted by director of operations Jim Russ, a middle-aged traffic-reporting vet who’s wearing chinos, a blue oxford shirt, and loafers without socks. He looks like a guy who just came back from a vacation on Block Island—which he did—except that he has the weary demeanor of a man who has spent 25 years ladling out bad news.

Next: What a typical day is like working for Metro Networks

Julie Wright and her colleagues feed traffic updates to some 100 radio stations and nine TV stations. Photograph by Kevin Koski

When he started at WTOP in 1986, he did traffic updates from 7 to 9 am and 4 to 6 pm. But traffic just kept getting worse, congestion spread into outer areas along with development, and now traffic is a 24-hour business.

On this morning, Metro Networks has more than a dozen reporters at work, some in offices and some in open cubicles around a central open space. All are chattering away, feeding some 100 radio and nine TV stations with traffic updates from Washington, Baltimore, Richmond, Raleigh, Greensboro, Virginia Beach, and Norfolk. The TV reporters have cardboard backgrounds behind them and remote cameras fixed to the furniture nearby, so they’re always on-air-ready. Everyone is tapped into a multitude of traffic-information sources, such as state Department of Transportation cameras, the Web site TrafficLand.com, emergency-scanner frequencies, and a traffic-tip hotline fed by drivers with cell phones. It’s a tsunami of information compared with the days when traffic reporting relied on fixed-wing aircraft circling the Beltway.

Russ is working the Baltimore region this morning, feeding his stations live and recorded updates every 15 minutes. He’s trolling his traffic sources via the bank of computers and radios before him, calling in to his police sources, and talking cogently to me all at the same time. Every few minutes, he breaks off practically mid-sentence to switch into a well-honed traffic-reporter voice of God and rip off another concise update. The multitasking ability, especially in the morning, is staggering.

Every day reliably delivers its own mini-crisis. And every once in a while—whether it’s snow, a chemical tanker, or some crazy guy on a tractor in the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pool—all hell breaks loose. When that happens, the traffic reporter is the most important reporter in town. “It’s like putting together a puzzle every day,” Russ says. “You don’t know what, when, or where. You just know it’s going to be something.”

I spend a few hours hanging out with the Metro Networks team. It’s a hyper-caffeinated frenzy of traffic buzz, with a war-room atmosphere. In the office next to Russ’s, a smell of hairspray wafts through the air. Inside, Julie Wright is feeding updates to Fox 5 TV, tweeting, Facebooking, doing her own makeup, working her own equipment and lighting, and gesturing energetically at a blank green wall which, by the time it hits TV screens at home, magically has road and traffic graphics superimposed on it. Almost anything can trip the chaos switch, she cheerfully explains—weather, sunrise and sunset, even the end of daylight-savings time, which makes the commute home darker and somehow unleashes the crazy-driver gene.

Out in the main bullpen, Lisa Baden—who, with her short, dark hair and careful speaking style has the manner and looks of a schoolteacher—reels off her TV and radio updates, trying hard to sound upbeat. She started in radio as a DJ and took what she thought would be a temporary job in traffic reporting when that gig ended. “Here I am after 20 years,” she says. “It’s the most secure job I’ve ever had in broadcasting because the traffic keeps getting worse.”

In addition to all the standard Web and electronic sources, Baden takes cell-phone updates from drivers she trusts (including a guy she refers to as Trucker Bob) and who routinely travel the routes she’s interested in.

I ask her what major transportation projects over the years seemed to make a difference. She pauses as she runs through a list in her head. “The Wilson Bridge,” she finally says. “That made a difference.” Then she giggles at the absurdity of coming up with only one example. “I commend them for trying, though,” she adds, no longer laughing.

As they swap tales of traffic disasters between updates, there’s a camaraderie among the Metro Networks team—likely born of ridiculous hours and the stress of absorbing a firehose of complex data points and translating them under metronomic deadline pressure into coherent and concise updates. Perhaps there’s also a bond that comes from working in a business built on bad news. It can’t be easy to be a routine purveyor of disappointment and frustration. Jamee Whitten, another Metro Networks reporter, once got so depressed sitting in her car and listening to a traffic update reporting congestion on road after road that she decided to always find at least one open road to include in her updates. “So I can say something like ‘Route 7 is wide open!’ ” she says.

I wonder whether drivers entombed in gridlock really take pleasure in knowing that someone somewhere is enjoying a fast ride, but I keep my cynical view of human nature to myself. In any case, it’s touching that she cares.

Next: Technology’s roll in avoiding traffic purgatory

One sunny afternoon, I hit the Beltway again, this time heading toward College Park. No one seems to have any plausible ideas about how to reverse the tide of vehicles inundating the road system. But I keep hearing about a guy named Michael Pack, who runs the Center for Advanced Transportation Technology (CATT) at the University of Maryland. I’m told he’s engaged in high-tech damage control, and if there’s anything that can help us avoid total traffic purgatory as Washington keeps growing, maybe it’s technology.

Pack has blond hair, rimless glasses, and the pale skin of a man who probably spends a lot of time bathed in the light of fluorescent bulbs and computer monitors. He ushers me into the CATT Lab, where he’s doing his damnedest to help the region create what he calls an “intelligent transport system.” We start in a large, open space that has screens all over the walls pulsing with traffic data and images. Students man consoles, slouched in chairs and focused intently on their computers. It has a situation-room feel, full of purpose and energy, and I feel a brief shiver of hope.

“You can’t build your way out of congestion,” Pack says. “So you have to be smarter about how you use what you’ve got.” He has a computer-science background and came to College Park in 2002 from the University of Virginia’s Smart Travel Lab. Maryland wanted to start something similar and gave Pack the freedom he wanted to go well beyond exposing students to transportation issues.

He figured that students who wanted to enter the field would be much better prepared if they were engaged in actually helping develop solutions. So Pack’s CATT Lab started to build systems that could be used by states and industry to confront the traffic beast. To do that, he opened the lab’s doors to computer scientists and transportation specialists but also to students specializing in everything from geography to digital entertainment to graphic design. He’s even got an archaeologist. It’s the sort of multitalented team used to create hyperrealistic video games like World of Warcraft, only Pack wants his users to battle epic traffic.

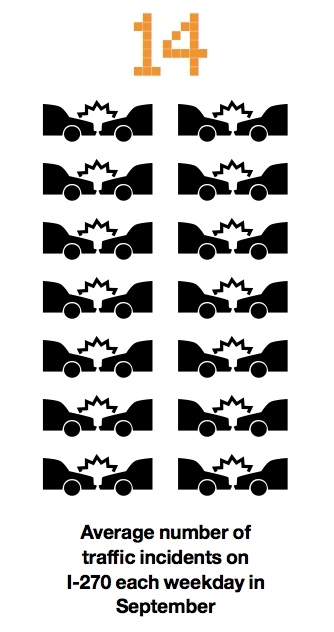

Pack’s approach starts with the fact that about half of congestion is a result of too many cars on the road and bad road design. He can’t do much about that. But he notes that the rest of congestion comes from “abnormal” or “nonrecurring” events—such as fender-benders, overturned tankers, road construction, police- and fire-department activity, and weather. Even the littlest thing, like a tire or dead deer on the roadway, can have a massive impact, particularly when lanes get closed down. I-270 alone averaged 14 incidents per weekday in September (and the region as a whole often experiences hundreds on a weekday).

According to Pack, every minute a lane is blocked, the chances of an accident go up by about 3 percent, a chain reaction that can quickly lead to paralysis on the roads. And each minute of lane closure can cause anywhere from four to ten minutes of congestion, depending on traffic volume. “It’s really important to get accidents off the road quickly and to pay more attention to how we manage incidents,” he says.

That’s the insight that gave birth to Pack’s evolving masterwork: the Regional Integrated Transportation Information System, known as RITIS. The core idea of RITIS is to hoover up the gigabytes of real-time data about major roadways that’s pumped out every second by a multitude of agencies and transform that into an intensely detailed picture of what’s happening in Traffic Land at any given moment.

This may seem like an obvious idea—the best ones always do. Yet when Pack came along, the departments of transportation in Maryland, Virginia, and DC had detailed pictures of their own traffic but there was no unified view of the region. Each state’s traffic picture would more or less go black when it reached a border. Anything over a state or district line was another DOT’s problem. Everyone used different software and protocols. Coordination across jurisdictions among police and emergency services was ad hoc.

Getting agencies to give their info streams to him wasn’t easy, but in exchange Pack offered access to RITIS. The system is now tapped into speed sensors; traffic cams; signal timing; weather forecasts; computer-aided dispatch for law enforcement, fire and EMS; and more. If it’s about traffic, or affects traffic, chances are RITIS is assimilating it. Already RITIS extends from New York City down to North Carolina.

Pack taps a keyboard and pulls up an image of the regional road network on a big screen in front of us. It’s alive with information, using color-coding and visual cues to convey what’s moving and what isn’t. Pack can drill down into any incident on the display—to find out what occurred, what agencies are on the scene, and what actions are being taken.

Next: Grand Theft Auto for the good guys

There’s a weird feeling of omniscience as we stare at what’s happening across a vast area of roads. Pack scrolls up and down the East Coast from Raleigh to the New Jersey Turnpike, which is in flashing red gridlock.

He then picks an incident from a previous day and shows me how RITIS can replay it in granular detail. Moving through the timeline, we start with a bad accident, we see responders arrive, we see lanes getting shut down for emergency services and a Medevac helicopter arrive. And then we see everyone . . . waiting and traffic backing up by the mile. The reason: The accident can’t be cleared until the accident investigator shows up to do an analysis, and the investigator takes an hour to arrive. It’s a perfect example of how poor incident management can screw up the world. “Now you know why not every agency is happy to share their data,” Pack says.

Because RITIS is so flexible, only about 40 percent of its 800 subscribers are from departments of transportation. The rest are agencies related to law enforcement, the military, and federal entities such as the National Security Agency, the Office of Personnel Management, the Secret Service, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Maryland governor Martin O’Malley is also a user. I ask Pack how far he plans to extend RITIS’s reach. “I would like us to be the national data integrators,” he says. Then he starts zooming out, so we can see not only the United States but other continents, too.

He doesn’t say a word, but you just know what he’s thinking.

Despite Pack’s sedate and earnest demeanor, he’s concocting ever more elaborate tools to worm his way deep into the DNA of traffic incidents. For example, he’s polishing a virtual-reality game that allows incident responders—fire, police, ambulance, tow-truck drivers, everyone who might show up in the real world—to assume their roles in his custom-engineered virtual reality. Wearing communication headsets and using a game controller or keyboard, they work their way through a variety of scenarios.

Pack leads me into a darkened room next to the main lab, where one wall is covered by a huge screen, and asks a student to cue a scene up. It’s eerie to watch Pack’s avatar move and talk at his direction. In a full-up recreation—which Pack describes as Grand Theft Auto for the good guys—multiple players walk, talk, put down traffic cones, and do all the stuff they would normally do, and it’s all replicated on the screen. For playback and review, every action of every person is recorded against a timeline.

Pack uses this Virtual Incident Management Training game to run trainings for first responders so they can improve speed, communication, safety, and traffic management. Participants can see the impact of every decision they make, and it can all be deconstructed afterward to analyze how things could have been done better. Did that police cruiser need to turn on all its roof lights (which slows traffic going the other way)? Did that fire truck need to be parked across that lane? Why was that cop standing in a place where motorists squeezing by either had to slow or risk hitting him?

Pack, I realize, is like Willy Wonka for transportation nerds, and the CATT Lab is a factory where wild ideas get transformed into technology that’s irresistibly fun. He’s even working on a “3-D virtual helicopter” version of RITIS that allows the user to fly over an uncannily realistic recreation of traffic on the ground. A few clicks and we’re airborne over the Mall, looking down on vehicles going every which way. We’re “flying” yet also sitting in chairs. My brain races to process what I’m seeing and its potential. One thing’s for sure. Pack and his ragtag, whiz-kid posse are on the verge of retiring the most recognizable icon of modern traffic reporting: the clattering helicopter, manned by a reporter who’s breathless over the sight of a six-lane pileup.

I ask Pack whether he thinks there’s a technological solution to traffic congestion.

“Oh, sure,” he says. “Completely automated cars that take the driver out of the equation, communicate with one another, and can travel at high speeds within six inches of one another.”

It’s a cool idea. Not even the Jetsons had cars like that, but with wireless, autopilot, and GPS technologies it seems doable. You could imagine our existing roadways being able to handle huge volumes of traffic, incident-free, if only the cars—not impulsive, distracted, unpredictable humanoids—were doing the driving.

By now, I half expect Pack to say, “Do you want to see one? We’re building a car like that right next door.” But he doesn’t—though he does mention that Google is experimenting with an automatic car. I ask how long before we can all stop driving and let the cars do the work. “Oh, a while,” he says. “Maybe 30 years.”

In the meantime, Pack is in favor of much more aggressive incident-clearance laws and procedures, including putting special bumpers on law-enforcement and responder vehicles and allowing them to push crashed or broken-down vehicles off the road quickly. “It would make a huge difference,” he says.

Next: Can Washington endure 30 more years of traffic hell?

It seems unlikely that Washington can endure 30 more years of traffic hell while waiting for the Google car or some other miracle.

I think back to my meeting with Ron Kirby. Toward the end, discouraged by the growing congestion he was predicting, I veered into fantasy. I asked what it would take to actually solve the problem. “Take politics completely out of the equation,” I said. “Can it be done?”

That’s the sort of question a transportation planner like Kirby lives to answer. “Yes, there is a way,” he said, with the aura of a traffic Yoda. “It would be a paradigm shift, but you could actually resolve this problem if you could price every roadway across the region.”

Given our anti-tax, car-worshipping, freeway-loving culture, asking drivers to pay for the use of roads—and not just the main ones—on a sliding scale that would increase with traffic is a thermonuclear idea. At the time, I had dismissed it because I figured there had to be a more likely solution. But if Kirby says it’s The Solution, then it’s worth considering.

As it happens, the Brookings Institution—a good place to go if you want to indulge in policy fantasies that make sense but that no seemingly sane politician supports—has studied the potential for using a congestion-pricing approach in Washington.

In 1952, economist William Vickrey, who went on to win a Nobel Prize in 1996, proposed charging variable fares on the New York City subway, to reduce rush-hour congestion, exactly as the Washington Metro does today. His insight was that pricing could be used not to reduce traffic flow but to spread it out more evenly through the day. He expanded on that idea by recommending similar variable-pricing plans for roadways, including the Washington region’s. (Vickrey wanted to use radio transmitters to track cars.)

Vickrey’s ideas for Washington’s roads were largely spurned, but they’ve been adopted in a number of cities, including Singapore, London, Stockholm, and Milan, with dramatic results. Vickrey had faith in his logic but understood the fierce debates variable pricing set off. “People see it as a tax increase, which I think is a gut reaction,” he said. “When motorists’ time is considered, it’s really a savings.”

Now Brookings, and Ron Kirby, would love to resurrect—or at least pilot—Vickrey’s prescriptions. COG and Brookings are engaged in a joint project to gauge public attitudes about the possibility of priced roadways, which is another way of saying they want to find out if widespread rioting would ensue.

Unlike in Vickrey’s day, the technology is simple. A GPS transponder would track a vehicle’s use of the roadways. Charges per mile would be assessed according to the time of day and level of congestion (overhead signs would warn drivers what price they’d be paying for the road ahead). The transponder would do all the math to assess the charges, and a regular bill would be issued (for privacy reasons, actual location data would remain secure within the transponder). The revenues could be used for dramatic roadway and mass-transit improvements, possibly replacing the gas tax. Some of the money could be used to subsidize lower-income drivers who would be hit harder by the fees.

These are details that would have to be hammered out, no doubt with blood spilled all over the floor. For now, Brookings proposes an initial pilot for the 1,500-square-mile area covered by the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. Brookings predicts that charges would average 9.3 to 15 cents a mile, though prices could go higher for drivers on the Beltway or 395 at peak rush hour.

The average commute in Washington is about 13 miles each way, so the charges for a rush-hour driver would definitely add up over the course of a year. But before you light your torch and try to crash one of Kirby’s meetings to assess public attitudes, consider the benefits. Only a serious rush-hour commuter would approach the $1,500 in estimated annual costs Washington motorists currently incur by sitting in traffic. And the whole point of congestion pricing is to allow the driver to control the costs. Anyone who adopted a more flexible commute strategy would save time and money.

One study—by Resources for the Future, a DC-based think tank—of comprehensive congestion pricing across the region says it would result in 19.4 million fewer vehicle miles traveled per day, a reduction of about 11 percent. A Federal Highway Administration study found that if traffic on congested highways could be reduced by 10 to 14 percent at peak times, there would be a 75-to-80-percent reduction in travel delays. There are other benefits: less pollution, reduced noise and oil consumption, fewer accidents.

The total estimated revenues from the congestion-pricing strategy would be $2.96 billion to $4.79 billion annually. That’s a lot of money coming out of drivers’ pockets, which is why there would be discussion of using congestion fees to replace some of the gas tax or the portion of local property and sales taxes that go toward local roads. But even if all the revenue from priced lanes were given back through the replacement or reduction of other fees and taxes—instead of going toward transit improvements—congestion pricing would at least give people a powerful incentive to do the right things: to live near work, to find ways to get to work that don’t involve a car, to cut back on driving, gas consumption, and pollution.

For the first time in my peregrinations through the Washington traffic conundrum, we’re looking at a solution that would do more than simply slow the predicted pain. The technology exists. It would open a stream of revenue that could be used to create a world-class mass-transit system. And it would make life on the roads bearable again.

There’s only one question: Is anyone ready to make it happen?

This article appears in the November 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.