One May night two years ago, Sean Bryant’s friends thought he might be dead.

Sean had just finished his third year at the University of Virginia and was spending a week relaxing with friends at a South Carolina beach condo. They were building a bonfire one night when someone realized that Sean wasn’t there; the last anyone remembered, he said he was headed for a late-night swim.

No one thought much of it at the time. Sean’s penchant for flights of physical fancy was part of his charm. He would scamper up trees at the slightest provocation and would bike the 100 miles from Charlottesville back home to Reston on a whim. He never saw a body of water he could resist jumping into. As a kid, he once licked a slug on a dare. Typical Sean, everyone would say, shrugging their shoulders. That’s just the way he is.

But on that night in South Carolina, Sean’s friends began to wonder if he’d finally gone too far. He’d been gone a long time. Uneasiness gave way to panic. His friends split up and scoured the beach. Someone called 911.

“There was a half hour where all of us really entertained the idea he had drowned,” says Ian Kim.

It seemed inconceivable that Sean could be dead. He was one of those people who sucked the marrow out of life. He was what everyone meant when they used that cliché “he had so much to live for.”

“If something had happened to him that night,” says Joel Young, who was on the beach trip, “we would have all said, ‘Look at this life cut short. He had so much potential. He had so much life in him.’ “

There would have been a story in the Washington Post,where Sean had already been profiled while he was still in high school: UVa Student Leader Missing, Presumed Drowned. They would have run Sean’s yearbook picture and trotted out a list of his accomplishments and honors–from his term on the Fairfax County School Board while a high-school senior to his appointment to the University of Virginia’s Board of Visitors.

They’d report that he was a National Merit Scholarship semifinalist out of Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, the magnet school in Annandale; that he had won a prestigious Jefferson Scholarship that gave him a free ride to Virginia. They’d probably mention that he was in the university’s elite government honors program and was slated to live in one of the 54 coveted rooms on the Lawn designed by Thomas Jefferson, an honor reserved for students who’d made outstanding contributions to the university. Somebody might describe Sean Bryant as Rhodes-scholar material. Somebody might say he was destined to be President of the United States.

And Sean probably would have hated it. He wasn’t one of those striving automatons who seem to flourish at Virginia, the kind one professor describes as having a kind of “transparent instrumentality” to their motives, the kind so focused on doing whatever it takes to land a Lawn room that other students belittle them as “pre-Lawn.”

That newspaper story wouldn’t have mentioned that Sean Bryant was goofy and spontaneous or that his nickname was Sugar. That he liked to fussily serve his friends tea and that he drove his Volvo like a maniac and had a knack for getting dirty. That he ate like a horse and could be moved to tears by Mozart and wasn’t afraid to be seen flying kites. They certainly wouldn’t say anything about how proudly he wore his bright yellow galoshes, described by his friend Elizabeth Kim as “the ugliest things I’d ever seen.”

It was that Sean Bryant–the tea-drinking, dirt-covered, kite-flying Sean Bryant–who turned out to be very much alive that night in South Carolina. Just as everyone was ready to give up on him, he came strolling back to the campfire, flushed from a run, completely mystified by his friends’ concern. I decided to go running when I got out of the water. What’s the big deal?

Until a breathtakingly beautiful morning that December, when Sean Bryant was found dead in his Lawn room. “UVa Student Leader Hangs Himself in Dormitory, School Says” read the headline in the Washington Post.

The article described Sean Bryant as “a superb student with unlimited potential.” He was, the newspaper explained, a “bright, articulate, hard-working student who was just a shining star.”

Nobody said anything about the yellow galoshes.

• • •

“Afterwards, no one was able to say, ‘I should have noticed back in November that that’s what he was trying to tell me.’ Usually, people come up with these kinds of things, even if there’s no validity to them. I was unable to find anyone who was even able to say something like that.”

–Jimmy Wright, director of the Jefferson Scholars Program

Trying to understand what happened to Sean Bryant is like sifting through the rubble left behind when an apparently stable wall collapses. Solid walls don’t fall down of their own accord, we reason, so we scrutinize each piece of debris, thinking we’ll zero in on one flawed brick: Behold! the failed relationship, the academic stress, the gnawing depression.

The truth about suicide is that it is rarely as simple as one flawed brick. Like Sean Bryant, some 20 percent of people who commit suicide display no obvious signs. Some, like him, not only seem free of obvious problems but have the kind of productive, successful lives that we assume inoculates them against suicide.

Sean left no note. But experts caution that the signs are always there, either hidden or overlooked. Solid walls, in other words, don’t just fall down.

Even if we find the suspect bricks, they often seem wanting. We cannot make things like academic stress and failed relation-ships logically add up to suicide because committing suicide is a seemingly illogical act. The answers, if there are any, are not just in the bricks we can see but in the mortar that binds them together. Certainly, no one on the outside could come to the conclusion that Sean Bryant–a healthy young man whose promise and talent radiated off him like sunshine–had reason to die.

“Whatever it was was not worth cutting his finger over, much less taking his life,” says anguished professor Larry Sabato, echoing a sentiment voiced by many. “But that’s easy for me to say. I wasn’t in his position.”

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for college students and claims more lives amongst people of all ages than homicide. Studies suggest that the kind of college student who commits suicide is most often the quiet, unassuming loner who falls through the cracks, not the kind of student whose death merits a story in the Washington Post.Although their deaths are no less painful, they are not usually students who have been nominated for Rhodes scholarships. They are not usually students on a first-name basis with scores of administrators trained to hone in on signs of crisis. They are not usually students so memorable that high-school cafeteria workers send condolence cards to their families.

• • •

“His was a life of such enormous promise. We fully expected him to do great, great things, not just for himself but for the commonwealth and, it’s not a stretch to say, for this country.”

–Kristen Amundson, a Fairfax County School Board member

In the personal statement he enclosed with law-school applications not long before he died, Sean Bryant made a confession. “Until this past year,” he wrote, “I suffered no greater permanent loss than that of my pet dog in third grade.”

Sean’s parents, Sallie and Stephen, were college sweethearts, transplanted Texans who moved to Reston in the 1970s so Steve, who had earned a PhD in political science, could begin work as a career bureaucrat while Sallie taught community college part-time and stayed at home with Sean and his older sister, Stephanie. They were the kind of good people who could believe unironically in the liberal promise of a planned community like Reston. They happily sent Sean to public schools, schlepped him to the Smithsonian and soccer practice, turned him on to hiking and camping, and packed him off for summers at camp in New Hampshire.

“I swear to God that we just had this ridiculously idyllic childhood and nothing bad ever happened,” laughs Stephanie Bryant, now 28 and a graduate student in history at Oxford.

Sean was an academically talented child, a voracious reader whose slug-licking élan kept him from crossing the line into geekdom.

In 1989, he started ninth grade at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology. There, Sean gravitated toward student government and earned a reputation as an effective politician who seemed idealistically committed to advancing causes rather than plumping up his résumé. As junior-class president, he delivered an impassioned speech about how even a white Christian like himself could feel compelled to take a stand against racism and anti-Semitism. His history teacher, Garfield Lindo, who is black, was so overcome that he had to leave class.

“I have said to students, ‘I’ve taught a student who I thought would one day be President of the United States,” says Lindo, who remained in touch with Sean after his graduation. “I said that in earnest. I believedhe would one day be President.”

Sean had his lighter moments, like the time he tried to adopt a groundhog while on a class trip to London’s Hyde Park–he had snuck the groundhog back into the hotel and asked to keep it.

While at Jefferson, Sean aspired to greater things than dealing with the prom committee and trying to get soda machines in the lobby. So in the spring of his junior year, he ran for–and won–the nonvoting student seat on the Fairfax County School Board. At his first board meeting, Sean opened a hornet’s nest by moving to amend the school district’s policy against verbal harassment to protect gay students, an issue a classmate had brought to his attention.

The board unanimously agreed to amend the policy but within weeks was facing heat. By protecting gays and restricting speech, 16-year-old Sean Bryant had managed to infuriate both the religious right and the ACLU. The flap merited stories in both the Post and the New York Times, although he missed his chance to be interviewed by the Times because he was out kayaking.

Sean was an island of calm in the midst of the storm. He dug in his heels and, as he later wrote of the incident, vowed to stay true to the pledge he’d made on accepting his seat on the board–a pledge to represent “all the students in allour schools, the actors, the debaters, the scholars, the kids in the auto-mechanics shops, the ones out learning construction trades, the would-be beauticians and the would-be lawyers, the computer buffs and the poets, the kid on parole and the unmarried girl who’s pregnant, the Boy Scout and the biker, the bops and the nerds.

“Students in our schools, both gay and straight, are the objects of verbal abuse about their sexuality,” he explained in one of his college-admission essays. “Some kids are made miserable by these comments, and that’s not right.” The incident encapsulated Sean Bryant’s political sensibilities: a sense of responsibility to those who were marginalized–he also fought on behalf of special-ed students–and a strong sense of what he believed in and what was worth fighting for.

Despite the potential for embarrassment over the gay issue–this was high school, after all–Sean, who by all accounts was interested in girls, never felt the urge to make clear that he was not going to be personally affected by the decision one way or another. That wasn’t the point. The point was that it was wrong, and he could do something to change it. The policy was amended.

When he was not generating national headlines, Sean maintained a fairly normal profile. He lettered in cross-country and track, although he did have a curious penchant for pushing himself to the limits of his endurance and usually vomited after finishing a race. He made friends with ease and, unlike most teenagers, moved from clique to clique without getting locked into any one social niche. He fell deeply in love with his first serious girlfriend and, like many teenagers, took their breakup hard. And while Sean had a way of comporting himself admirably with adults, he was not obnoxiously precocious.

“Sometimes there are kids who get along real well with adults but other students look at them and say ‘Oh, yeah,’ ” says school board member Kristen Amundson, delivering the last two words with the kind of dismissiveness high schoolers have for such a kid. “That was not Sean. He was extraordinarily well liked and respected.”

Before he graduated, Sean took another shot at making history, trying to change the state law that forbade student members of school boards from voting.

“It’s crucial that we not only have a voice but the power to change our education for the better,” Sean told the Washington Post, which wrote a story on the matter. This time Sean’s efforts failed, but he seemed to like using government as an agent for change.

• • •

“A Hell of a Lot of Fun”

Thinking that military service might be a prerequisite for a political career, Sean won an appointment to the US Naval Academy but turned it down to accept the Jefferson Scholarship to the University of Virginia, where he was accepted into the honors program and enrolled in the Naval ROTC. Sean’s sister attributes his brief stint in the military–he had dropped out of ROTC by his second year–to the fact that he was an adrenaline junkie. “I believe he joined ROTC because he thought they’d let him jump out of a helicopter,” she says.

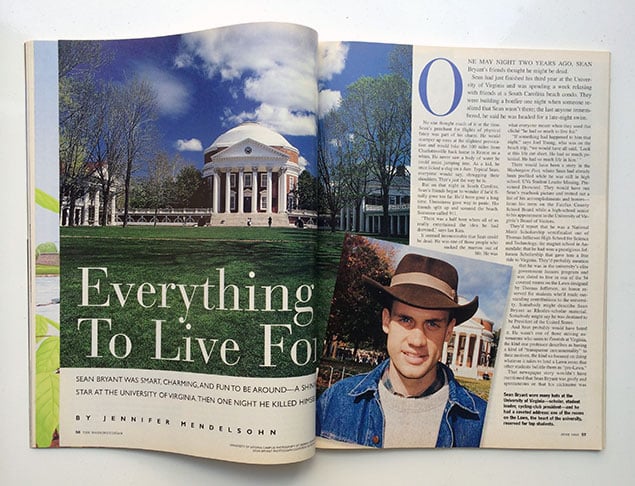

Sean Bryant could not have been more perfectly suited to UVa, a place whose “primary business,” according to a recent report for the Jefferson Scholars program, has always been that of “producing leaders for a self-governing people.” Founder Thomas Jefferson, the report says, envisioned the university as a “training ground for those who would take on the burdens of responsibility in a free society.”

Nearly 175 years have done little to dilute the Jeffersonian legacy. Students enjoy a degree of self-governance rare on other college campuses. The newspapers operate without faculty advisers, and the honor and judiciary committees, both of which have expulsion authority, are student-run.

The prevalence of self-government may be responsible for a UVa subculture in which talented students try to outdo one another in their service to the university. Students compete for unglamorous jobs that other universities have to pay people to do–at UVa it is a privilege to be selected as a resident adviser or a campus tour guide.

And people joke that only at Virginia would it be considered the ultimate honor to land one of the 54 tiny rooms on the Lawn, where residents have to walk outside to a separate building to use a bathroom.

Sean Bryant took to this scene like the proverbial fish. By the end of his freshman year, having served on the First-Year Council, Sean won a schoolwide student-council election and set his sights on becoming the student member on the Board of Visitors, arguably the top political position for a student. He was selected to live in Monroe Hill residential college, which attracts interesting and accomplished students.

Sean settled into a comfortable existence at UVa. He was accepted into the high-minded if slightly eggheady Jefferson Literary and Debating Society. He managed the Student Union building and raced with the cycling club, eventually becoming its president. In the spring of second year, Sean was elected a vice president of the student council.

Sean was one of five students picked for the prestigious–and rigorous–honors program for government majors, modeled after the Oxford tutorial system. Entrance into the program is highly competitive, requiring a minimum grade point average of 3.7.

Despite all his accomplishments, Sean “had a good way of being ambitious without people getting turned off by it,” says his friend Alvar Soosaar, who served on the student council with Sean.

It wasn’t that Sean didn’t understand the power of government and how to use it. It’s that nobody ever questioned his motives or dedication. He ambled earnestly through student political circles like Jimmy Stewart’s Jefferson Smith, with a sincere passion for unsexy causes like the Libraries Committee and the Asian Student Union, of which he was actually a member. His pet project was creating a course-evaluation guidebook so students could give their feedback to professors.

Throughout his college career, Sean continued to champion the rights of those outside the mainstream–gay students, people of color, poor people–while avoiding strident identity-based politics.

“If there were people who were disadvantaged, left out, or locked out,” says Carlos Brown, president of the student council when Sean was a vice president, “he wanted them to have the opportunity to get in.”

Although he was intense and focused, Sean maintained a robust social life and always found ways to deal with stress. Ever the outdoorsman, he would often take off on long bike rides or hikes or runs. Once or twice, Sean–still sporting hair short enough to pass muster for ROTC–shaved his head bald to blow off steam. Typical Sean, his friends would say.

Sean had a way of never taking his student-leader role too seriously, of not allowing his buttoned-down side to suppress his goofier side, the one that flew kites and climbed trees and served tea. He often wore bow ties to student-council meetings, but he also would show up at social events in sweaty biking clothes. He once went to a party dressed head to toe in leather.

“Initially, I was surprised he was as successful as he was,” admits government professor Michael Smith, who developed a close relationship with Sean. “He had none of the politician glad-handedness about him. He was a quiet presence that grew on you as opposed to someone who comes in and dominates the room. In some way, it was a tribute to the students’ discernment that they elected him. They responded to something in him that was not a guy with a big smile and a lot of posters up around.”

People may have responded to the fact that Sean Bryant was an original, right down to his yellow galoshes. Only Sean would wade into a pond to catch frogs in the middle of the night or could talk you into canoeing when you had tons of work to do. Only Sean would make you late for class because he insisted on photographing you in a field of tulips that caught his eye out a bus window. Only Sean would dance with you in the middle of a crowded restaurant.

Everyone assumed he would someday be President of the United States. But Sean Bryant was also a hell of a lot of fun.

• • •

In the spring of 1995, when Sean was in his second year at Virginia, he was forced to come to terms with a loss more devastating than that of his dog. After almost 30 years of a picture-perfect marriage, Steve and Sallie Bryant came to Charlottesville on Easter weekend to tell Sean they were splitting up. According to Sallie Bryant, the news was unexpected: Her husband came home one day and announced that the marriage was over. (Steve Bryant chose not to be interviewed for this article.) “I know it seems impossible, but I really had no clue,” she says.

Sean took the news hard, not only in the first few months after his parents separated but throughout the next year. His mother offered more than once to pay for counseling, a suggestion to which he was politely indifferent, even though she made clear that both she and his sister, Stephanie, were trying it.

In May 1996, Sean was dealt another emotional blow when his mother’s father, to whom he had been very close, passed away. He was the first person Sean knew well who had died, and the experience–Sean left school and went to Texas so he could hold his grandfather’s hand and sing hymns to him in the days before his death–shook him.

During the summer of 1996, when his parents’ divorce was finalized and Steve Bryant remarried, Sean continued to talk about the breakup with professor Michael Smith. Smith also suggested that Sean seek counseling, saying that he’d found it helpful in working through his own divorce. To the best of anyone’s knowledge, Sean never went.

He was apparently most unnerved by the idea that his parents’ relationship may not have been as perfect as he’d thought. He seemed “distracted” by how suddenly it all came apart, according to his roommate Erik Su, and told several people that he was angry with his father. He found himself wondering whether his happy family had been nothing more than a façade–whether his parents had actually ever wanted children. He often expressed fears that he was never going to find a fully satisfying romantic relationship.

Nobody felt that Sean’s reaction was inappropriate or excessive: It was a difficult situation, but he was dealing as best he could.

“He had times that I had been concerned about him, but there was never a time that I didn’t think he was probably more emotionally secure and emotionally healthy than just about anyone I knew,” says Sallie Bryant. “He seemed to be working through things in a logical way.”

• • •

“Where Do You Go From Here?”

By that fall, it appeared that Sean was coming to terms with a hard year and going about his business as usual. Now in his fourth year, Sean was living on the Lawn, which many see as the quintessential UVa experience. With its two colonnaded rows of student rooms, one on either side of the domed Rotunda, the Lawn is the heart of the university–you can almost feel the weight of Jefferson’s presence. Competition is fierce for the rooms, most of which have a fireplace.

Life on other fronts seemed promising for Sean that fall. He was apparently happy over his deepening relationship with third-year student Megan Thunder, a student-council vice president, and was thrilled to be the student member on the Board of Visitors. Once again, he set himself apart.

“He had the ability to distill a problem to its essence better than most people I’ve ever met,” says board member Wick McNeely, a Charlottesville businessman. “He was a star among stars. And I’m not comparing him to students, I’m comparing him to other board members.”

But as the semester wore on, Sean faced disappointments in arenas in which he had never seriously faltered before: He was competing for things and having trouble coming out on top.

He began the arduous process of applying for the Rhodes scholarship he had always coveted. In typical fashion, Sean had no trouble impressing the members of the Rhodes committee at UVa.

“Sometimes you see people of his age come into that kind of interview full of talent and ideas but given to fairly simple ways of thinking or assessing the world or problems,” explains English professor Jahan Ramazani, a former Rhodes scholar who sat on the committee. “There was a keen, analytical subtlety that really impressed you. He was able to see shades of meaning and shades of difficulty in attacking a problem.”

Sean won one of several endorsements from the UVa committee, but he was not invited by the state committee to move forward to the next round of interviews, although other UVa students were.

Sean got the news and smashed a bottle of rubber cement against the wall of his Lawn room. “Yeah, I’m okay,” he told his mother over the phone. “But I’ve got a big mess to clean up.”

He seemed to agree with professor Larry Sabato about what a crapshoot the whole thing was. But he was disappointed and confused.

“He really had wanted to be a Rhodes scholar, and when he didn’t get that, he was kind of at a loss as to what would happen in lieu of that because he had always really planned ahead,” explains Elizabeth Semancik, who dated Sean in first and second year and remained close friends with him. “When he was first year, he was making out lists of what his life was going to be three years, four years, five years down the road. I think the Rhodes scholarship was a big chunk of that, one he assumed would always be there–and when it wasn’t there, he didn’t know how to fill in those years.”

For perhaps the first time, Sean was uncertain about what came next. He was applying to law school but was said to be struggling with the personal statement on the applications. He was toying with going on to graduate study in public policy and was preparing to take the GRE the second week in December. He tried his hand at the campus recruiting process, knowing that prestigious consulting firms often dangled high-paying offers at hotshot undergrads. But the interviews apparently didn’t go well, and he hadn’t been getting any offers. By late November, after botching an interview with McKinsey, an international consulting powerhouse, Sean told his mother–now an executive with a Big Six accounting firm–that he had no idea how to navigate the Byzantine world of business, and he worried about his prospects.

While he expressed concern about all of these things, no one detected any behavior that would have suggested he was in crisis.

“Sean still seemed like Sean. He had the same concerns a lot of us shared–realizing he’d done a lot at UVa and thinking ‘where do you want to go from here?’ ” says Bryan Hancock, also a Lawn resident and a Rhodes nominee that December. “I saw somebody with things they wanted to talk through, like everybody else. Probably more thoughtful, probably more concerned than everybody else, but still somebody going through the same fourth-year problems like everybody else.”

“Sean, like everybody else, had ups and downs,” agrees his mother. “I always felt like as long as he was talking about them, and he wasn’t despairing, and his activities weren’t dropping off–all those sorts of things–that that’s just life, that’s what life’s all about.”

A few days before Thanksgiving, Sean wrote a column in a student newspaper in which he seemed to be saying just that. He wrote of the difficult year he’d had and of preparing for his first Thanksgiving since his parents’ divorce and his grandfather’s death.

“These changes make me think a lot about giving thanks for the joys I have had,” he wrote. “Countless chess games lost to my grandfather after dinner at the kitchen table while he drank coffee and ate Gran’s cookies; eating Cheetos and pears with my parents and sister while hiking by a waterfall in the Blue Ridge.

“This Thursday at dinner I will remember that dear to me which I have lost,” he went on, “give thanks to God for granting something precious to lose, and pray for friends and family that I can give thanks for again and again, year after year.”

• • •

The first Saturday in December, Sean and his good friend John Stambaugh, a fellow cyclist and a UVa grad, got together to watch a movie before Sean hunkered down for exam week. Stambaugh can’t help but recall that the film–Manon des Sources, the sequel to the French hit Jean de Florette–includes a scene in which a man distraught over unrequited love hangs himself from a tree. He remembers that Sean indifferently agreed with his comment that the suicide note was well written.

As the week wore on, nobody who came into contact with Sean appears to have seen anything out of the ordinary, not even the kind of marked improvement in mood that sometimes precedes a suicide. He was “friendly and outgoing” Sunday night, playing charades at an honors-program spaghetti dinner. On Monday he seemed “loose and happy” during dinner at Monroe Hill.

Elizabeth Semancik’s last memory of seeing Sean alive was at about one o’clock Wednesday morning, December 11, when he roused her, still in her pajamas, out onto the Lawn so that he could take her picture. Typical Sean, she thought. He said he wanted to use up a roll of film, which she saw him leave out to be mailed for developing. Later that day, he also remembered to mail a birthday gift to his father. It would arrive two days after Sean’s death.

At around six o’clock Wednesday evening, Sean sent an e-mail to his uncle in Thailand, apparently in response to a question about whether he was job hunting. “Yeah, I thought it would be a good idea to try the working world for a little while before hitting the books again,” he wrote. “Unfortunately, I am doing rather poorly at securing prospects. Some of my friends have spent several months unemployed after graduating–I hope not to be in their shoes come May, but I am beginning to worry.”

The e-mail closes with a question: “Will you be visiting Texas anytime soon?” he asked. “Yours, Sean.”

Sometime thereafter, Sean headed to a pizza study break for Jefferson Scholars with Ian Kim, his good friend and next-door neighbor on the Lawn. Ian recalls that Sean was a bit down–he mentioned his disappointment over the Rhodes competition and that he was having a problem getting professors to take his beloved course-evaluation book seriously–but that nothing seemed out of the ordinary.

• • •

No Answer

Later that night, Sean’s girlfriend Megan Thunder came to see him in his Lawn room. Although Megan declined to be interviewed for this article, she told several people that she and Sean argued that night. Megan told Sallie Bryant that they had been fighting over the fact that they hadn’t been spending enough time together. (Sean had previously told his mother that Megan thought he was too overextended to make their relationship a priority.) Megan told Sallie that Sean was “upset” when she left his room sometime after 9 PM and that he didn’t answer her when she asked if he was going to be okay.

Not long after, Sean’s neighbors began to hear an earsplitting medley of thumping music–starting with alternative rocker Beck’s Mellow Gold,according to Ian. When Megan returned to talk to Sean about a half hour after she’d left, the music was blaring and he would not answer the door. She prevailed on Ian to help her, but despite their repeated knocking and their attempts to peer through the mail slot, they could not coax him out. They gave up, deciding that he must have left the room and forgotten about the stereo.

After returning to her off-campus apartment, Megan called Sean, but he didn’t answer the phone. She left an apologetic message on his voice mail.

By about nine o’clock Thursday morning, Ian Kim had had enough. He’d barely slept, had an exam to study for, and Sean’s stereo was still going full force, skipping on the same annoying clip of Sheryl Crow. Ian asked the head resident on the Lawn if she could unlock Sean’s door and turn the stereo off. He waited beside her as she opened but then quickly shut the door. Ian opened the door himself and saw just enough to know what had happened.

Sean’s body was hanging from the bookshelves over his bed, suspended by a belt from his bicycle hook.

It’s likely that Sean was already dead by the time Megan came back to see him.

“My knowledge of Sean tells me that if he had been there and alive, he would have opened the door, because he’s not a sulker,” says Sallie Bryant. “He would have wanted nothing more than to have her standing there, and he would have opened the door.”

It is possible that Sean was still alive when his friends came by–either he really had left his room, as they suspected at the time, or he was ignoring them. There was one report of a student who thought she saw someone fitting Sean’s description studying in the library in the wee hours of Thursday morning. Elizabeth Semancik, who lived two doors down from Sean, thinks someone knocked on her door in the middle of the night but admits she may have dreamed it. And Sean’s next-door neighbor Mary Fader was reported to have heard a thump or movement in his room at 2 or 3 in the morning.

Because the medical examiner could not pinpoint the time of death, the uncertainty will always remain.

In the days after Sean died and his dazed family came to pack up his belongings, Ian Kim remembers going into Sean’s room and flipping through the stack of CDs that had been playing that night. He came across Mellow Gold,which contains the angst anthem “Loser.” (“I’m a loser, baby, so why don’t you kill me?”) The CD insert has a picture of a figure hanging by the neck.

• • •

“I Can Totally See Him Doing It”

The mystery of Sean’s suicide will forever lie in that gap between external appearances–he had so much to live for, nothing was out of the ordinary–and the reality of his death, which the university police and medical examiner deemed a straightforward suicide. There were no signs of foul play, although several friends and faculty members entertained notions that Sean had been murdered.

There are as many explanations of that gap as there are people who have looked for one. The dry assertions of mental-health experts, full of statistics and risk factors, may ring false to the Bryants, who’ve lost a vital, adored member of their family. What makes sense to Sean’s professors may still baffle his girlfriend. What his sister can easily see her little brother doing may not add up in his grandparents’ eyes.

And while the rumor that Sean killed himself because he was stressed about writing his senior thesis may have satisfied those who only knew Sean from the story in the newspaper, it seemed absurd to friends like John Stambaugh. “It was a college campus during exam week,” says Stambaugh. “If you’re notstressed, you feel detached and alienated.”

Sallie Bryant was put in the position of having to deny to the Reston Timesthat Sean’s death had anything to do with a rejection from medical school, to which he had never applied. A story made the rounds in Northern Virginia that a UVa student had hanged himself because he got a question wrong on the Law School Admissions Test.

• • •

No one knows the extent to which Sean may have been harboring suicidal thoughts in the weeks before his death. Many of those who knew him well say that Sean wasn’t hiding anything; his death, in their eyes, was not the culmination of some long crisis but rather a spike of much the same impulsivity that made him so much fun to be around.

There is something comforting about hearing Sean’s sister, Stephanie, talk about it this way, as if Sean had died in a hang-gliding accident or had drowned that night on the beach in South Carolina.

“It seems sort of strange, but when my mother told me, I wasn’t even really surprised,” she says. “I was horrified and angry, but my response was more like, ‘Sean. No! Big mistake! What were you thinking?’ It wasn’t, ‘Oh my God, why did you do such a thing like that?’ Because I can totally see him doing it.”

She sees Sean sitting in his room after Megan left, feeling angry and frustrated. She thinks he was probably overwhelmed by all the balls he had in the air and upset that another relationship was not perfect. She pictures Sean, goaded on by the throbbing blare of the stereo, killing himself in a trancelike flash–an impulsive, irrational burst that happened too quickly for him to think better of it.

“When he felt intensely happy, he picked us up to dance around. When he was intensely in love, he’d write beautiful love poetry. When he felt intensely angry, especially at himself, I can see him thinking self-destructive acts,” Stephanie explains.

• • •

For Stephanie and others, Sean’s death is consistent with his life. He thrived on the kinds of physical challenges that require a person to override rational fears and act quickly, to narrow the gap between thought and action. He died, they say, much the same way.

Experts concede that “behavioral impulsivity” is associated with increased risk of suicide but say this is different than thrill seeking or spontaneity. The impulsivity they cite is a reckless inability to control one’s urges, regardless of consequence. This kind of impulsivity often will take a toll prior to suicide–in drug abuse and explosive violence, in truancy and stints in jail.

It certainly doesn’t apply to the Sean Bryant who had trained to be an emergency medical technician with the local rescue squad, who always wore a bike helmet, and who was notorious for always having the right tool on hand to do any job. It doesn’t fit with the Sean so focused on the future that he had been known to leave a party if he spotted drugs, worried that it might come back to haunt him in his political career. But what about the Sean Bryant who rock-climbed with abandon and was always the first to jump off a cliff into water?

“If there are signs he engaged in those activities without any fear of danger when there was danger, that moves more toward the threshold,” says Dr. Lanny Berman, executive director of the American Association of Suicidology.

Like when he climbed under a barbed-wire fence so he could shimmy up a radio tower that caught his eye? Like when he drove off the road after convincing himself that he could climb into the back seat of his station wagon to retrieve something while he was still driving?

Regardless of where we set that threshold, something made Sean Bryant cross the line from cheating death to pursuing it, a sign that some basic self-preservation instinct had given way. Healthy people do not kill themselves, says the literature from one suicide-awareness group. Solid walls just don’t fall down. Impulsivity may have been one of the flawed bricks that led to the collapse, but experts insist that it alone could not have been enough to kill him.

“What kind of tunnel vision had to be there for him to be so focused on using this belt and this hook for this purpose without having any other thoughts, saying, ‘Wait a minute. Stop. Go get drunk. Go talk to a friend. Go beat your fist against the wall’?” asks Dr. Berman. “What makes this thought become the singular focusing and moving thought in his remaining minutes? The healthy mind doesn’t get that unifocal.

“It was an extraordinarily foolish decision that may have been made on the spur of the moment,” he continues, pointing out that he can only speak generally about the situation. “But it had a foundation to it. It didn’t occur out of nothing.”

Hanging oneself also takes some logistical deliberation; Sallie Bryant admits she would have been less surprised if Sean had jumped out a window.

And for Elizabeth Semancik, the inconsistency is too great. How could a young man who would spend a week planning the minute details of a picnic make the most important decision of his life on the spur of the moment?

“Maybe that makes it harder for some people, but I don’t think it does, because I think it means that he still was himself. He was keeping in character,” she says. “It wasn’t like this sudden stroke of madness where he didn’t know what he was doing. I think he did think about it, and he logically had decided why it was what he had to do.”

• • •

Was It an Accident?

Other people, including Sean’s best friend since childhood, Bliksem Tobey, believe that Sean’s death might have been accidental, a macabre experiment that went awry. Sean always had to try everything once. Could he have been curious about the experience, thinking that he could pull himself upright at the last minute only to find he couldn’t?

“Whether or not it was his first attempt, I don’t think he really intended it to be his last,” says Ian Kim.

“It may well be that there are some places of despair nobody touches. But I am convinced in my bones that this was not intended; I can’t reconcile it with what I know of him,” agrees professor Michael Smith. “Emotionally I see that [the accidental explanation] fills this need for me to not have failed this student whom I loved. But intellectually it still makes more sense than any other explanation.”

The medical examiner who handled Sean’s case says he feels confident about having ruled Sean’s death a suicide.

• • •

Inner Demons

Even if Sean’s crisis had escalated lightning-fast that evening –the fight with Megan was what experts label a “precipitating event” but by no means the actual cause–many people feel that there had to have been more to Sean than met the eye. There had to have been “places of despair” that nobody touched, inner demons buried so deeply and carefully that they never seemed to intrude on his day-to-day functioning.

“We assume one has to be in despair [to commit suicide], and therefore there ought to be symptoms of despair,” explains Dr. Lanny Berman. “But there are lots of very troubled people who lead very quiet lives of very quiet desperation, who have public personas and private torment.”

Professor Smith has wondered if Sean could have been struggling with his sexuality, if his commitment to gay rights had been more personal than he let on. Studies suggest that sexual-identity issues are responsible for as many as 30 percent of adolescent suicides, although the statistics are highly controversial.

Smith ultimately found the explanation “too pat,” given that he’d specifically tried to draw Sean out on the matter–to no avail–as they worked on his Rhodes essay, which detailed Sean’s efforts on behalf of the gay community. The feeling among Sean’s friends and family is that he wasn’t hiding anything, that his interest in gay rights was just another facet of his liberal ideology.

• • •

Some people believe that the answer to Sean’s death must lie in his extraordinary abilities–that his success could have been the source of his downfall. There is evidence, albeit largely anecdotal, of a growing number of suicides among high-achieving young people.

“It used to be that suicide was a function of depression or bad circumstances–that people were either in trouble in school or disabled or had a bad family background,” explains UVa clinical psychologist Peter Sheras, who has studied adolescent suicide. “In the past ten years, we’ve seen a rise in suicide and suicide attempts among people who appear to be models of functioning–captains of football teams, valedictorians, people from intact families without socioeconomic pressures–that don’t seem to fit the previous model.”

In 1995, Sarah Devens, a Dartmouth junior whom Sports Illustrated called “the best female athlete in the school’s history,” took her life with a shotgun. The week before Sean died, 16-year-old Jessica Miller of the District leapt to her death from the Taft Bridge. The Washington Postdescribed her as “the picture of student success.”

In Remembering Denny,Calvin Trillin’s poignant memoir of the suicide of Rhodes scholar Roger Hansen, one of Hansen’s acquaintances says, “The way I see promise is that you have a knapsack, and all the time you’re growing up they keep stuffing promise into the knapsack. Pretty soon, it’s just too heavy to carry. You have to unpack.”

For some high achievers, striving for perfection in the outside world is a coping mechanism, a way to fulfill a deep-seated need–for approval or for love or for feeling special. If this were the case with Sean, it might explain why he sometimes seemed so self-critical, why at times nothing his friends could tell him about how wonderful he was seemed to stick.

“Sean was always interested in embodying excellence. He wanted to be the most quintessentially excellent person he could be,” explains Ian Kim. “I think ultimately, Sean achieved all these respectable things at UVa–the Board of Visitors, the course guide, living on the Lawn–but to him, those accomplishments, in the end, didn’t change the way he felt about himself.”

Sean’s concern that he might never be able to sustain a relationship–he lamented to friends that he had expected to meet his wife in college–might have been a manifestation of the same phenomenon. He may have been hoping a successful relationship could provide the same kind of external validation that winning awards could. “One thing I want out of a relationship is the feeling that I am loved,” he explained in a letter during his first year at UVa. Sean’s syntax may be coincidental, but it is striking; most people want simply to be loved.

“I think in the end, [the relationship issues were] more a key factor than anything,” says Sallie Bryant, who has searched desperately for any explanation. “He longed for a deep, rich relationship with a woman. He always felt intensely about the person at the moment, and no matter who broke it off, it always hurt him very much. Even if it wasn’t quite working, he so wanted it to work that it really disappointed him when it didn’t.”

When someone accustomed to leaning on external crutches reaches for them and they are not there, the situation can become dangerous.

“When the person relies on perfectionism or having high standards as a source of self-esteem, and it begins to falter, that can feel extremely threatening to one’s sense of oneself,” explains Dr. Ginger Wright, director of UVa’s suicide-prevention program, begun just months before Sean died.

• • •

The theory that Sean was some stereotypical overachiever –one who couldn’t handle losing–doesn’t ring true for most people who knew him, although his drive haunted some of those who came in contact with him.

“At the time, he just looked mature and balanced,” says Sam Miller, assistant to UVa’s vice president for student affairs. “I guess you could also say looking back it was intense and extreme.”

Wayne Cozart of the Alumni Association agrees: “I’m one of the few people who say this, but there was an intensity to Sean that wasn’t fathomable. There was something in his eyes that I couldn’t define. I always used to say that he was going to be President of the United States or he was going to be at the top of the Texas Tower.”

On some unconscious level, the accumulation of perceived defeats large and small–the divorce, the Rhodes, the McKinsey interview, fighting with Megan–could have been disastrous to Sean’s internal balance, the mortar that held him together.

Some, like psychologist Peter Sheras, say that our culture has become desensitized to these kinds of crises, that we are so blinded by our admiration of people like Sean that we tune out their distress calls. Jimmy Wright of the Jefferson Scholars program, however, believes that Sean eluded any radar.

“The standards of expectation that folks like Sean have for themselves are so high that those of us who work with them have to be on guard for a misguided but nonetheless real sense of failure when no failure exists,” says Wright. “The idea that you could view not winning the Rhodes as a failure–it’s very real to the person, but it’s so foreign to the rest of us who aren’t even in the league.”

The matter is clouded by what many see as the most insidious characteristic of high-achievers: They are often skilled at summoning up vast reserves of public polish in the midst of gut-wrenching agony. They have far more to lose by being perceived as floundering and can even deceive themselves into believing they are not.

Although Sean was generally regarded as someone who wasn’t afraid to open up about his problems, some friends felt that underneath his happy-go-lucky exterior, there was a piece of him you couldn’t quite get to.

“With Sean, there were always walls that he didn’t let down,” says Ian Kim.

But Elizabeth Semancik thinks that Sean’s problems were inverse to the high-achiever syndrome. He wasn’t stressed by having so many pressures, she says. If anything, he thrived on it.

“He had reached a peak of feeling like he had done everything there was to do,” she says. “You’re fourth year, you’ve accumulated this incredible résumé, and then you start looking ahead at what you’re doing and you really don’t know where you’re going, and all of the options of where you might be going seem somehow less glorious than where you are at the time. You’re not going to be getting awards, you’re not going to be the person on the front page of the newspaper all the time. I think if anything it was, ‘I can’t believe it’s almost over. And this is as good as it’s going to get.’ “

• • •

“You’re just not given to understand things like this. But it’s not that different from any other tragedy. How do you understand a traffic accident? How do you understand the Holocaust, for God’s sake? . . . Even if you try to place a rational explanation, it doesn’t change it, it doesn’t do anything for you. It’s almost like it’s irrelevant.”

–Sallie Bryant

A lot of people still talk of Sean Bryant in the present tense. A year after his death, his ashes scattered in the places he loved, Sean’s name still graced one of the speed-dial buttons on his mother’s telephone.

“I’m still kind of expecting him to walk in through the door,” admits friend Alvar Soosaar.

Sean’s absence has become a presence of its own. Professors in the government honors program now stand watch like mother hens over students they used to leave to their own devices.

“I find myself calling more frequently,” says Larry Sabato. “I call them out of the blue and say, ‘How are you, okay? What are you doing? Are you feeling pressured? Are you upset about anything?’ “

Some fear that it cheapens Sean’s memory to learn from his death, like looting a graveyard. But others talk of becoming freer, somehow truer to themselves. They’ve learned to be better friends, better children, better lovers. They tell of priorities rearranged, of finding joy in the everyday pleasures they once overlooked in their haste to move forward. Just as everyone always said he would, Sean Bryant left the world a better place.

“What I take away from all of this is that the most important thing is that you have a sense of peace,” says friend Joel Young, who now works for a nonprofit group in Belfast. “Beyond that, you’ll be provided for.” Those lessons, however life-affirming, can be wrenching–bitter pills to be swallowed with a steely resolve.

“Do you learn from it?” Sallie Bryant wonders aloud, her eyes welling with tears. “Yeah, you do.” Her voice is little more than a plaintive whisper.

“It’s not worth it, though.”

This article appears in the June 1998 issue of Washingtonian.