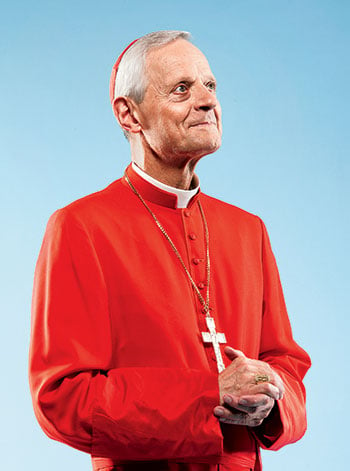

Three years ago, Cardinal Donald Wuerl, the Roman Catholic archbishop of Washington, tapped Monsignor John Enzler to take over Catholic Charities, the primary social-welfare arm of the archdiocese. The move took many by surprise. Catholic Charities helps not only Catholics but anyone in need, which last year meant treating more than 15,000 patients at its clinics and in physicians’ offices (200-plus doctors donated some $6.7 million worth of medical services to the poor last year), serving 5.5 million meals to the needy, and making more than 1,800 beds available every night, from shelters for the homeless to permanent housing for adults with disabilities.

Enzler is a beloved priest who has used his people skills to make his name as a successful pastor—and fundraiser—at two of Washington’s most prestigious parishes: Our Lady of Mercy in Potomac and Blessed Sacrament in Chevy Chase DC. Administration of a multifaceted social-welfare agency wasn’t on his résumé; he was more accustomed to baptisms and confessions than budgets and conference calls.

But Wuerl didn’t want a bureaucrat. He was looking for a “pastor to the poor,” Enzler explains: “Cardinal Wuerl says that we have a moral obligation to take care of the poor. At the macro level, he looks for people who can do the work.”

• • •

Ever since Pope Francis walked out on the balcony of St. Peter’s Basilica for the first time last March, Catholics and non-Catholics have been intrigued by his simple lifestyle, his frankness, and his exhortations to care for those in need. But as his papacy has progressed, the question for Vaticanologists has become how the new pontiff will give organizational heft to his rhetoric.

An answer came in December, when Francis named Wuerl to the Congregation for Bishops, a committee that recommends candidates to fill bishoprics in more than 5,000 dioceses around the world. The position—which he’ll fill while continuing as archbishop of Washington—gives Wuerl a crucial voice in determining the next generation of Church leaders.

Just as the College of Cardinals had picked Francis, an Argentinean bishop known for his pastoral approach to diocesan management, the pope has entrusted the scouting of new bishops to Wuerl, the man who chose a pastor like Monsignor Enzler to run Catholic Charities. The key to advancement, insiders understood, would be to infuse even administrative functions with pastoral zeal.

That’s not what the wider world took from Wuerl’s appointment. The American whom Wuerl is replacing on the Congregation for Bishops is the ultraconservative former archbishop of St. Louis, Cardinal Raymond Burke. In that city, Burke built a reputation as the US church’s most prominent culture warrior. He made front-page news during the 2004 presidential campaign by saying that Senator John Kerry—the Democratic candidate and a Catholic—should be refused Holy Communion at Mass because of his pro-choice stance on abortion.

In the mainstream press, the switch was reported as a significant shift and a rebuke of Burke by Pope Francis, who wrote in his first official teaching document, Evangelii Gaudium, that the sacrament of Communion “is not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak.”

But Burke and Wuerl have a history on the issue that gives Wuerl’s selection a personal tinge. Like most bishops, he counters Burke’s arguments about Communion that it’s not a priest’s job to arbitrate political positions through the Eucharist. Wuerl has said he discerns two approaches to reaching out to people: “One is the pastoral, teaching mode, and the other is the canonical [or legal] approach. . . . I believe if we teach our people, we will not have a problem with our politicians.”

But most bishops don’t have nearly as many Catholic politicians coming to their Communion rails, and Wuerl’s stance has made him a target for Burke’s criticism.

In March 2009, Burke gave a video interview to the pro-life activist Randall Terry. When Terry criticized Wuerl and Arlington’s bishop, Paul Loverde, for not denying Communion to pro-choice politicians, Burke said nothing in their defense.

Wuerl responded in an interview with AOL’s Politics Daily that withholding the Eucharist “wasn’t a way we convinced Catholic politicians to appropriate the faith and live it and apply it.” He dismissed politicizing the scarament as “the new way now to make your point.”

More than a year later, when Pope Benedict XVI made both Burke and Wuerl cardinals at the same consistory at the Vatican, Wuerl reportedly reached out to Burke, suggesting that, whatever problems they’d had in the past, it was time they became friends. Burke, according to someone who observed the scene, rebuffed the overture.

Given their history, Wuerl’s appointment, the conservative political journal the American Spectator said, “deserves a special place in the annals of in-your-face papal politics.”

One can make too much of the politics of Wuerl’s new assignment. Popes don’t normally use staff decisions to settle personal scores. Nor should Wuerl’s promotion be interpreted as a triumph for Catholic progressives. He’s no firebrand, and only the most arch of archconservatives would consider him a liberal. Instead, he has a track record as a moderate intent on managing staff, reconciling budgets, and seeking compromise in a pastoral manner.

In May 2012, Georgetown University invited Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius to speak at graduation just as Catholic hospitals and other religious institutions were fighting a provision of the Affordable Care Act mandating health-insurance coverage for birth control for all employees. Wuerl issued a statement criticizing the decision to select “a featured speaker whose actions as a public official present the most direct challenge to religious liberty in recent history.” But the kerfuffle didn’t prevent him from appearing last October at the kickoff of the school’s new Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life beside Georgetown president John DeGioia.

“Now, with Pope Francis, [the initiative] looks like an easy step,” says John Carr, director of the center. “But in the beginning, when prospects were uncertain, Cardinal Wuerl offered personal support for its mission and its location at Georgetown.”

Says Stephen Schneck, director of the Institute for Policy Research & Catholic Studies, a think tank at Catholic University: “Cardinal Wuerl is not afraid to criticize, but he’s more likely to simply roll up his sleeves and work for whatever good can be achieved.”

If Wuerl is a signal to the Church, then, it may be that Francis is hoping the cardinal’s tenure will be one of steadiness and seasoned decision-making. “It would be hard to name someone in our country who has a broader experience of the life of the Church,” says Bishop Blase Cupich of Spokane. “His opinion is held in high regard by his brother bishops because he has consistently shown that he has the capacity to prudently and objectively reflect on his experience.”

• • •

It’s a part Wuerl has played before. As a young priest, he studied in Rome and returned there to a post in the curia—the Church’s central administration—after a stint as a parish priest in Pittsburgh, his hometown. But when Pope John Paul II wanted to rein in a provocatively liberal bishop of Seattle in 1985, he appointed Wuerl auxiliary, with the difficult job of acting as the bishop’s Vatican minder.

As bishop of Pittsburgh, a seat he held from 1988 until coming to Washington in 2006, Wuerl was one of the first bishops to announce a “zero tolerance” policy for clergy sex abuse, even successfully battling a Vatican decision that ordered him to reinstate a priest he had suspended after the cleric was arrested for molesting a minor.

A moderate like Wuerl, and the bishops he chooses, may signal a change in how the Church relates to the nation. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, headquartered in Washington, has long been a prominent voice in politics. For most of its history, the group steered clear of partisanship, advocating for the poor, a move that aligned them with Democrats, but against abortion, which aligned them with Republicans. In the past ten years, however, the bishops have tilted to the right, insisting that issues such as abortion and same-sex marriage had priority over other subjects. Their partisan edge cost the bishops some of their cachet, especially among their natural allies in social-justice circles.

Wuerl—though he may not have Enzler’s experience with rank-and-file parishioners—may restore some of the American Church’s profile in terms of putting the disadvantaged first.

In Washington, from his relative remove as cardinal, Enzler says, Wuerl has already shown his concern: “He guarantees we have the resources we need, giving more than $1 million from the annual Cardinal’s Appeal. There is no micromanagement, just great commitment, great trust. He really supports our work.”

Enzler adds that Wuerl is proving himself more adept at hands-on ministry. “A year ago, we began a weekly program to serve dinner to homeless men and women who don’t get a lot of food at the shelters,” he says. The cardinal, who attends board meetings at Enzler’s headquarters on G Street, Northwest, across from the Martin Luther King Jr. library, has mingled with the 250 or so people who come to eat each week.

“Watching Cardinal Wuerl, seeing him greet the people, not dressed up in any regalia but as a simple priest, listening to them, wanting to be a part of their situation, it’s really impressive,” Enzler says. “He’s completely comfortable with the people who come for dinner.”

Now the cardinal wants to visit Food & Friends, the program that assists people with HIV and other illnesses. “He always asks me, ‘What’s next?’ ” Enzler says. “He wants to be a part of our work.”

Even as Wuerl moves higher in the Vatican’s sometimes remote hierarchy, he seems to have acquired, in Pope Francis’s phrase, the “smell of the sheep.”

Michael Sean Winters (mswkna@aol.com) is a visiting fellow at Catholic University’s Institute for Policy Research & Catholic Studies and author of the National Catholic Reporter blog Distinctly Catholic. This article appears in the March 2014 issue of Washingtonian.