David Gregory was driving through the mountains of New Hampshire when he got the call that no TV personality ever wants to answer. It was August 14, 2014, a Thursday. Gregory and his wife were on their way to pick up their kids from summer camp, according to friends. On the line was an executive in NBC’s New York headquarters, telling Gregory once and for all that his run as moderator of Meet the Press was over.

This wasn’t exactly news to the Sunday-morning host. Meet the Press’s ratings had been tanking for several years. And for the last week or so, Gregory and the network had been busy negotiating his exit package.

But the deal wasn’t finished, and Gregory had planned to be back in Washington to host the show that Sunday. So the call from New York took him by surprise.

The executive explained that NBC wouldn’t be able to keep his departure under wraps much longer. Rumors of Gregory’s demise had been swirling for several months. Navel-gazers in the Washington and New York press corps had been gleefully printing every last shred of gossip they could forage. Now reporters were circling once again, and it looked like the network was about to lose control of the story. The announcement would have to come today.

Gregory and his bosses wanted to break the news themselves, and they had to scramble to finalize the official line on his exit.

They were too late.

Before they could get their stories straight—and before they finally sewed up Gregory’s severance—CNN reported that he was out and that his chief rival, NBC White House correspondent Chuck Todd, would take over as moderator.

After being scooped, Gregory was compelled to take to Twitter to put his own spin on the ouster. “I leave NBC as I came—humbled and grateful,” he tweeted. “I love journalism and serving as moderator of MTP was the highest honor there is.”

It was the final indignity in a chaotic and embarrassing fall from the top.

For six years, David Gregory had owned the most coveted job in political journalism. Meet the Press first aired in 1947 and is now the longest-running show on network television. It started as a half-hour press conference and evolved into the place where Presidents came to make news—John F. Kennedy called it “the 51st state.”

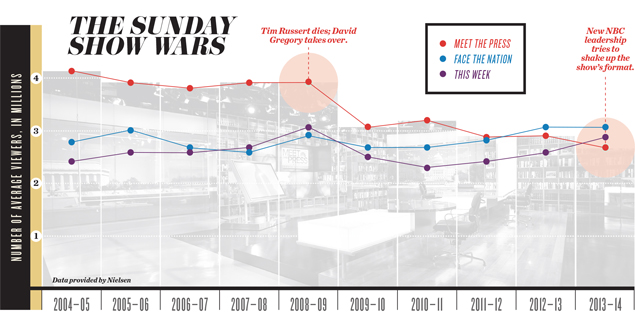

But under Gregory, the most prestigious political franchise in Washington media had collapsed. Although he took over at a time when eyeballs were declining across the board because of 24-hour cable news networks and a constant stream of internet talking heads, no Sunday show plunged further than his. Between 2008, when Gregory took over, and last summer, just before he left, Meet the Press lost 43 percent of its viewers and dropped from first to third place in the ratings.

It would be easy to write off Gregory’s ouster as a garden-variety network-talent hit job. No one in TV can hide from the numbers, and Gregory’s record had made him a clear target for NBC executives. But there was more to his downfall than Nielsen data. Nasty internal sabotage, TV-size egos clawing for his job, and a new NBC News boss looking to blow up convention all contributed to Gregory’s demise.

For Comcast, NBC’s new corporate owner, there was more at stake. The fight wasn’t just about saving a national treasure. A strong Meet the Press helps more than the bottom line—it provides instant credibility in Washington for a notoriously despised company looking to control both the shows we watch and the pipes that deliver them.

As such, a close look at the clash is also a chance to get a close-up on the present and future of TV news.

Meet the Press was never David Gregory’s dream job—nor was he the network’s first pick after Tim Russert died.

America loved Russert. The plump, rumpled newsman was a consummate Washington operator. Yet he projected himself as the folksy son of a garbage collector who’d never lost touch with his roots. The show, which predated its CBS and ABC competitors, was a third-place backwater when Russert took over in 1991. Within six years, it was on top. Critics moaned that Russert wasn’t the inquisitor he pretended to be, but on his watch the show turned into a cash machine that reportedly earned a $60-million annual profit.

Because the program reached an affluent, educated, and influential audience—and consistently beat CBS’s Face the Nation and ABC’s This Week—it could charge higher advertising rates than other news shows. “It was always a profit center,” says Bill Wheatley, a former executive vice president of NBC News.

All that changed on a Friday the 13th in June 2008. Early that afternoon, Russert stepped out of his office in NBC’s Washington bureau, greeted a colleague with his customary “What’s happening?,” and entered a sound booth to record voice-overs for that Sunday’s show. Minutes later, his heart gave out.

Russert’s sudden death traumatized the network. After Tom Brokaw interrupted afternoon programming to share the news, bouquets piled up outside the bureau and condolences poured in from Bill Clinton, Conan O’Brien, politicians and celebrities alike. Meanwhile, Russert’s coworkers wrestled with the shock of having watched the country’s most beloved political journalist die on the job.

The situation looked equally devastating from a commercial standpoint. Russert was only 58—and NBC executives had never drawn up succession plans for Meet the Press. Nor was there an obvious heir. How would they replace an irreplaceable figure?

Their first thought was Brokaw. The former Nightly News anchor was the only on-air figure with the standing to follow Russert, according to a former senior NBC executive. But Brokaw, then 68, declined the offer because he didn’t want to be tied down on a weekly basis.

PBS’s Gwen Ifill was considered, as was NBC’s Andrea Mitchell. Also in the running: Chuck Todd, the NBC News political director whom Russert had hired shortly before his death.

Like his former boss, Todd had sources all over Capitol Hill, compulsive work habits, and a fascination with Washington’s machinery. “He reads The Almanac of American Politics for fun,” says Reid Wilson, a Washington Post reporter who once served as Todd’s assistant.

Todd also pined for the moderator’s chair—and lobbied aggressively for it. “He saw himself as the heir,” says the former senior NBC executive, and “let it be known that he was the one that Tim Russert wanted.”

But choosing Todd had drawbacks. He was 36 then and had been on the air only a short time. Despite all Todd’s jockeying, the former executive says the network only briefly considered him—the brass believed he was simply too raw for such a high-profile position.

Gregory, the network’s chief White House correspondent, on the other hand, was a solid, safe choice. Silver-haired and striking, he was an accomplished broadcaster who had a rapport with the officials he covered—George W. Bush nicknamed him “Stretch,” on account of his six-foot-five frame—but who was also known for his confrontational exchanges with White House spokesmen.

And, no small consideration, he had long been the show’s principal guest host. “It made a lot of sense,” says Domenico Montanaro, who was then a political reporter for NBC News.

Meet the Press had never been Gregory’s biggest ambition, according to people close to him, simply because he figured Russert would never leave. He knew the high-stakes job would come with added pressure: The host of a show is on the hook for ratings in a way that even a senior correspondent never is. And Russert was an impossible act to follow. “He felt the prestige but also the burden of carrying on that show and that legacy,” says a close friend.

But Gregory pounced, and from the moment his promotion was announced, political elites eager to get exposure on the show treated him differently. “All of a sudden he was everybody’s best friend,” says a close friend. “I joked, ‘Wow, you’ve gotten so much more handsome.’ ”

The network, meanwhile, gave his old White House job to Chuck Todd.

• • •

NBC was owned by General Electric at that time, and the network was the oddball of the conglomerate’s industrial empire, accounting for only a tenth of its revenue. Although corporate leaders at GE knew little about broadcasting, they thought of Meet the Press as a hot property, former NBC executives say, and occasionally summoned Russert and other on-air personalities to GE board meetings to impress investors.

That was about the extent of their involvement, though. So long as NBC’s news division hit its quarterly financial targets, GE left the journalists alone. “There was no interference whatsoever,” says a person close to Gregory.

Everything changed after GE decided to get out of the news business.

In 2009, it announced it would sell a controlling stake in NBC Universal to Comcast, the Philadelphia-based cable behemoth. NBC was struggling at the time: The network had dropped to fourth place in the ratings overall, behind CBS, ABC, and even Fox. But Comcast CEO Brian Roberts believed that to succeed in the 21st-century media landscape, the cable company needed to do more than control the distribution of TV—it needed to control the making of the content, too. Comcast already owned E!, the Style network, and a couple of cable sports stations. NBC was to be its biggest prize yet.

Before that could happen, there was a hurdle to clear: Washington.

The Comcast/NBC deal faced intense scrutiny from lawmakers and regulators who worried that this kind of industry consolidation and vertical integration would squelch competition. Minority advocates weren’t thrilled about the idea, either. They were concerned the merger might reduce diversity throughout the industry.

Meanwhile, Comcast’s terrible reputation—its poor customer service regularly lands it on lists of America’s most hated companies—wasn’t likely to help it make its case. The company had previously hired a Washington research firm, Penn Schoen Berland, to gauge perceptions of the cable giant among influencers in DC and across the country. The results were ugly. That made the outlook for regulatory approval even trickier.

What Comcast did have was a super-connected political fixer named David L. Cohen.

Cohen, whose legendary stint as chief of staff to Philadelphia mayor Ed Rendell in the 1990s was chronicled in Buzz Bissinger’s book A Prayer for the City, is plugged in all over DC. “I have been here so much,” President Obama joked during one of two fundraisers at Cohen’s Philadelphia home, “the only thing I haven’t done in this house is have Seder dinner.”

Cohen knew about the money and shoe leather required to win friends in Washington. After taking over Comcast’s government-affairs office in 2002, he had steadily beefed up the company’s presence in the capital. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, Cohen expanded its lobbying team from 31 bodies in 2002 to 103 in 2009, when the merger was announced, and increased its lobbying spending more than five-fold over the same period.

To rally political support for the merger, Comcast’s political-action committee handed out campaign cash, and Cohen worked to head off the concerns over diversity. Between 2008 and 2010, Comcast’s corporate foundation donated more than $3 million to 39 minority groups that wrote letters to federal regulators in support of the NBC deal. Comcast and NBC Universal also worked out an agreement with advocacy groups guaranteeing increased “minority participation in news and public affairs programming”—so long as the deal went through. And in 2009 and 2010, Comcast gave $155,000 to an organization founded by the Reverend Al Sharpton, who ended up endorsing the merger.

The campaign paid off. In January 2011, Washington approved the deal. One week later, NBC signed Cohen’s old boss, Ed Rendell, to an on-air contract. At MSNBC, which Comcast also owns, Sharpton landed a talk show. A spokeswoman for Comcast says the company is a “long-standing supporter” of minority groups and had nothing to do with Sharpton’s hiring. She also says Cohen played “little to no role” in securing Rendell’s contract.

Shortly after the merger went through, Roberts, Comcast’s CEO, went on MSNBC’s Morning Joe and talked up how excited he was to take over NBC. Roberts had special praise for the news division.

It was, he said, the cable company’s new “crown jewel.”

• • •

From the start, it was clear the Comcast regime was going to take a more hands-on approach with NBC than GE had. The innocent, even positive, explanation for this is that Comcast knew more about making good television than its industrial predecessor did. The more worrying interpretation—especially to some in the news division—was that the company saw the Washington bureau as a way to win goodwill among the Beltway powers who might green-light its continued expansion.

Among the first new Comcast faces to show up at the bureau after the merger was none other than Cohen, who had smoothed the way for the deal. Cohen didn’t involve himself in the news agenda. But as Comcast’s chief political operator, he became the most visible emissary of the company’s soft-power initiative. (The company declined Washingtonian’s request to interview him.) NBC staff watched him cozy up to the network’s top celebrities at high-profile social functions. And when it came time for the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, the network’s new leadership made room at the tables for Comcast executives and the public officials they needed to influence.

At the 2012 dinner, for instance, Cohen sat with Chuck Todd, Today hosts Al Roker and Savannah Guthrie, and Republican congressman Eric Cantor, who was then House majority leader. Afterward, deejay Funkmaster Flex spun records and Rachel Maddow mixed cocktails at an MSNBC-sponsored party where Comcast execs mingled with lawmakers, Capitol Hill aides, and media muckety-mucks. This was a significant change from the GE era, when corporate executives rarely attended the festivities.

The merger was felt inside the newsroom, too. Staffers in the Washington bureau were under pressure to book minorities on their shows so Comcast and NBC could make good on their promises to civil-rights groups. Employees compiled data on the ethnic makeup of on-air guests to ensure they were in compliance, according to a person familiar with this research. While more diversity on television is, of course, a good thing, this corporate edict had less to do with making high-quality TV than with pleasing the institutions journalists are supposed to be out covering.

Comcast also had an even more personal way of sucking up to Washington. Its government-affairs team carried around “We’ll make it right” cards stamped with “priority assistance” codes for fast-tracking help and handed them out to congressional staffers, journalists, and other influential Washingtonians who complained about their service.

A Comcast spokeswoman says this practice isn’t exclusive to DC; every Comcast employee receives the cards, which they can distribute to any customer with cable or internet trouble. Nevertheless, efforts like this one have surely helped Comcast boost its standing inside the Beltway and improve its chances of winning regulatory approval for its next big conquest: merging with the second-largest cable provider in the country, Time Warner Cable.

Announced in February 2014, the $45-billion deal could become the most consequential corporate transaction in a generation. If it goes through, it would put Comcast in control of 35 percent of the nation’s broadband internet coverage. Combined with its robust cable penetration and its ownership of NBC content, that’s unparalleled reach into America’s living rooms.

All Comcast needs, once again, is Washington’s blessing. Which is why Meet the Press, the company’s marquee Beltway property, is not just another show.

Before Comcast came along in 2011, David Gregory thrived at Meet the Press. Top White House officials returned his phone calls and took the time to explain complicated policy matters, Gregory’s friends say. Leading figures in business and politics helped him craft questions. “He loved it,” says a close friend.

For three straight years, Gregory kept Meet the Press in the number-one slot. Every six months or so, GE’s CEO, Jeff Immelt, would call to say, “You’re doing a great job,” according to Gregory’s friends.

But even while the show remained on top, viewers were leaving the network, and its lead over CBS and ABC gradually shrank. The slow bleed eventually became a crisis. By late 2012, Meet the Press had lost a quarter of its viewers and, after 16 years, surrendered its ratings crown to Face the Nation. Gregory took the blame.

Though he was a master of the technical aspects of broadcasting—crisp, polished, with the ability to turn the garbled instructions that entered his earpiece into lucid questions or commentary—many of his talents were largely invisible to viewers. When it came to on-screen presence, some thought Gregory lacked the basic DNA to connect with the die-hards who made up his audience. Unlike Russert, he wasn’t a classic political animal. Gregory didn’t spend his days working Capitol Hill sources, he treated research like a chore, and he rarely broke news—a high priority in a saturated media environment.

To some, it began to seem as if he saw Meet the Press as just another job. They took umbrage at how much time Gregory spent hobnobbing at his vacation home on Nantucket, where other NBC big shots like Russert and Chris Matthews also liked to “summer.” Gregory sometimes spent the bulk of his work week on the island, according to a person familiar with his travels, and returned to DC with only a couple of days to prepare for Sunday’s show. Other times, he was inexplicably absent from the Washington bureau and couldn’t be located. A person close to him disputes this, arguing that Gregory, who had worked the White House beat for eight years, loved politics. “His life was in Washington,” the source says. “He was not an absentee executive.”

Gregory could be prickly: condescending to lower-level staff and arrogant to others, traits that didn’t make him terribly popular at the bureau. And he wasn’t a good ambassador for Meet the Press on NBC’s other platforms. While Russert had regularly provided political analysis on Today and Nightly News, Gregory appeared on those shows less frequently. He had long been seen as a top contender to replace Matt Lauer as host of Today, and some saw network rivalries as the problem. “Brian Williams and Matt Lauer didn’t put [Gregory] on their shows because they were threatened by him and didn’t like him,” says a former senior NBC executive. Another source familiar with the situation contends that NBC shows didn’t book Gregory because he was rarely around. A person close to Gregory disputes this, saying he was “always around.”

By early 2013, NBC—which had now been under Comcast’s control for two years—began a concerted effort to revive Meet the Press. The network hired a New York branding firm, Elastic Strategy, to organize a series of focus groups to help diagnose the show’s problems, according to people familiar with the research. There was one key finding: Viewers liked Gregory well enough; they just didn’t feel they really knew him.

NBC executives zeroed in on this disconnect. Even Gregory’s critics admit that—when he’s off camera—he brims with charm and charisma; his dead-on impersonation of Tom Brokaw puts colleagues in stitches. Yet this vibrant personality somehow disappeared when the camera turned on.

The network decided it needed to learn more about Gregory to help him establish a stronger connection with his audience. So it had the branding consultants interview his wife, friends, and colleagues, according to people familiar with the research. Producers later encouraged Gregory to mention his family and his Jewish faith on the air to help viewers get to know him better.

Nothing worked. In August 2013, Meet the Press’s ratings plummeted to 21-year lows. That was just one of several big problems at the network.

Meet the Press Timeline

A Short History of the Longest-Running Show on Television

November 6, 1947

The first “Meet the Press” airs on NBC, with co-creator and radio producer Martha Rountree as host. The 30-minute format includes one guest and a panel of questioners.

November 1, 1953

Rountree steps down, and journalist Ned Brooks (far right)becomes host.

November 7, 1954

“Meet the Press” gets a rival when CBS debuts its Sunday show, “Face the Nation.”

January 3, 1960

Senator John F. Kennedy appears a day after announcing his run for President.

January 1, 1966

Lawrence E. Spivak, original co-creator of the show with Rountree, becomes host following Brooks’s retirement.

November 9, 1975

Gerald Ford is a guest—a first for a sitting President. After the broadcast, Spivak departs and Bill Monroe, a former NBC Washington bureau chief, takes over.

November 15, 1981

“Meet the Press” gets even more competition on Sundays when ABC launches “This Week With David Brinkley.”

September 16, 1984

Former CBS reporters Roger Mudd and Marvin Kalb become moderators, a move meant to shake things up now that ABC’s “This Week” has become a serious rival.

May 10, 1987

NBC chief White House correspondent Chris Wallace becomes host but stays only through the end of 1988.

January 29, 1989

Another change: Garrick Utley, NBC’s “Sunday Today” anchor, takes over for the next three years.

December 8, 1991

Tim Russert becomes the show’s ninth host. The next year, it expands to an hour. By 1997, Russert brings up ratings by a total of 40 percent.

December 11, 2001

Viewers have risen to an average 4.1 million a week. NBC signs Russert to a 12-year contract, believed to be the longest in TV history.

September 8, 2002

Russert interviews Vice President Dick Cheney about alleged weapons of mass destruction in Iraq the same day that administration-planted stories about WMD appear in the New York Times. Later, Russert is criticized for going too easy on Cheney and giving him a platform to drum up support for the war.

November 28, 2004

Three weeks after an election in which moral values factored heavily into President George W. Bush’s reelection, Russert does a segment on morality and religion with reverends Jerry Falwell, Richard Land, Al Sharpton, and Jim Wallis. Afterward, Gloria Steinem and leaders of Planned Parenthood and other groups criticize the show for bias, given the absence of a female and the pro-life position of three of the guests.

June 13, 2008

Russert, the show’s longest-serving moderator, dies of a heart attack at NBC’s Washington bureau. Tom Brokaw begins filling in while NBC scrambles to replace Russert.

December 7, 2008

David Gregory becomes the new moderator.

May 6, 2012

Vice President Joe Biden appears and voices support for same-sex marriage.

December 23, 2012

After the Newtown massacre, Gregory interviews National Rifle Association head Wayne LaPierre and holds up a 30-round magazine— illegal in DC. Prosecutors decline to charge Gregory.

August 14, 2014

“Meet the Press” has hit record lows and conceded its top slot in the ratings to “Face the Nation.” Gregory exits, and NBC announces Chuck Todd as the next host.

September 7, 2014

Todd’s debut—an interview with President Obama—has 2.98 million viewers, vaulting “Meet the Press” to the top of the ratings for the first time in many months. The victory will be short-lived.

NBC’s three most prestigious news franchises—Nightly News, Today, and Meet the Press—underpinned its credibility and its revenue for decades. But now the country’s most venerable broadcast-news network was falling apart.

ABC’s Good Morning America had toppled Today in the war for morning viewers, and its evening newscast was cutting into NBC’s lead among the key 25-to-54-year-old audience. Meet the Press was faring the worst of all—it was now in third place on Sundays.

To turn things around, NBC hired an executive named Deborah Turness as its new president, making her the first-ever woman to run a network news division in America. Turness had been the editor of the news unit at the British network ITV, but she wasn’t your average television suit. The Englishwoman “renowned for ripping up the rule book,” according to the Guardian, had been married to a former roadie for the Clash and once competed in the “Peking to Paris” off-road car race. She had swagger.

As soon as she arrived, Turness was repeatedly asked if she was going to can Gregory.

According to executives, she did have a mandate to “transform” the whole news division. As she told the New York Times, “NBC News hadn’t kept up with the times in all sorts of ways, for maybe 15 years.” It had, she said, “gone to sleep.”

But Meet the Press wasn’t her first priority, and besides, Turness was fond of Gregory. She’d met him three months earlier at a secret get-together, when, wary of leaks during the hiring process, NBC had furtively checked her into a hotel and had on-air talent and executives come to her room for one-on-one meetings. Turness found Gregory funny and likable. Moreover, the two shared a similar enthusiasm to shake up the show’s format. So she decided to back him while she first went about fixing Today, the network’s most lucrative property.

Turness finally turned her attention to Meet the Press in January of 2014. Right away, it was clear that she was tired of the status quo. Like a lot of people, Turness considered contemporary Sunday shows a snooze. Every week, they put the same talking heads on air to rehash the same stories that cable TV and the internet had been chewing on all week. Turness didn’t see much value in that, and she told colleagues she thought NBC had treated Meet the Press like a Fabergé egg—too precious to touch.

After weeks of focus groups and ratings analysis, Turness and the Meet the Press team identified three areas for improvement, according to NBC executives. First, the show needed to book higher-profile newsmakers instead of trotting out washed-up ex-officials and overexposed senators. Second, Gregory’s interviews had to produce something buzzy—a comment, an exchange—that would propel the next day’s news cycle. Turness often joked with Gregory about how British journalists treated their politicians with less reverence than the American media did, and she wanted Gregory to get more aggressive, according to sources familiar with these conversations.

While these ideas weren’t radical, the third one sparked controversy.

Turness told colleagues that the show should retain its intellectual bent but there was no reason for it to be so stuffy. Watching Meet the Press felt like work, and she told the staff she wanted a program that was fun and surprising. A guilty pleasure. Something that might even make you laugh. The country’s most esteemed political talk show, she concluded, needed to loosen up.

Turness had all kinds of ideas for how to pull this off. She considered bringing in a studio audience, as you’d see on Ellen or Saturday Night Live. She thought about moving the show to New York City, where the number-two-rated This Week sometimes filmed. She suggested that Gregory stack newspapers on his desk to give the set an intimate, coffeehouse feel. She insisted on quickening the show’s pace with shorter interviews and more pretaped segments to mix things up.

And she pressed the staff to book more politically active celebrities that non-white, non-male, non-senior citizens—the people who aren’t watching Meet the Press—might be drawn in by.

Gregory chafed at these changes, people close to him say, fearing they were too radical and would cheapen the brand. But he complied. On one show, rapper will.i.am joined former White House communications director Anita Dunn, Utah congressman Jason Chaffetz, columnist Kathleen Parker, and Chuck Todd for the roundtable segment. Instead of loose, as Turness wanted, the result was utterly stiff.

“I’ve just got to get you to tweet that you were going to be on in the morning, which you did,” Gregory said to will.i.am.

“I hooked it up,” the rap star replied.

“Yeah, you hooked it up,” Gregory said.

At one point, Turness suggested that Gregory have a live band close out the show to commemorate the death of Nelson Mandela. Gregory was appalled, people close to him say. Although he recognized the need to broaden the program’s appeal to a younger, more diverse audience, he worried that Turness’s approach was about to turn Meet the Press into a political gong show.

• • •

The new boss wasn’t Gregory’s only problem. Suddenly, stories about the palace intrigue at Meet the Press began appearing with suspicious frequency. By March 2014, only two months into Turness’s turnaround effort, rumors that Gregory was on the chopping block had gained so much traction that he asked NBC to respond and quell them.

“I cannot be more declarative about David—[he] is our guy, is going to be our guy, and we are really happy with him,” Turness’s top lieutenant told the Huffington Post.

But after that, the drums only beat louder. On April 20, the Washington Post reported that the Meet the Press research conducted back in 2013 to beef up Gregory’s personal narrative had included “commissioning a psychological consultant to interview [Gregory’s] friends and even his wife.”

NBC denied that allegation, insisting that the person in question had been a branding—not psychological—consultant. But the story exploded on the internet, turning Gregory into a laughingstock and precipitating a fresh round of speculation about his job security.

Once again, Gregory demanded that NBC executives make a show of support, and Turness obliged. In a memo quickly leaked to media writers, she called the press reports “vindictive, personal and above all—untrue” and reiterated her “support for the show and for David, now and into the future, as we work together to evolve the format.”

Gregory was becoming a spectacle, and it was clear to him, friends say, that this was no accident—someone was planting these stories in the press to discredit him. The question was who.

Gregory had no shortage of rivals at NBC, and speculation centered on the two who were represented by powerful and media-savvy agents: Joe Scarborough, a client of Ari Emanuel, the Hollywood superagent and the inspiration for Ari Gold on HBO’s Entourage, and Todd, a client of Jay Sures at United Talent Agency.

Scarborough, the Republican congressman turned MSNBC talking head and host of Morning Joe, had been after Gregory’s job for years, according to former NBC employees. And inside MSNBC’s New York offices, Scarborough is known as a prima donna who doesn’t respond well to “no.”

“He constantly clashes with [MSNBC president] Phil Griffin,” says a former NBC employee. “There are times when he would just not even talk to [Griffin].”

When Gregory was in the hot seat, some thought Scarborough reached for the knives. And the staff wouldn’t have welcomed him in the moderator’s chair. In 2012, NBC executives had given Scarborough a shot at guest-hosting Meet the Press in Gregory’s absence, according to sources. But the network’s news division protested. Republican presidential hopeful Rick Santorum was booked for that week’s show, and letting Scarborough interview a fellow conservative would undercut the franchise’s nonpartisan bona fides. As a compromise, Savannah Guthrie moderated and Scarborough led the roundtable.

In 2013, the New York Post had reported that Scarborough was in discussions with NBC about taking over the Sunday edition of Today, which airs before Meet the Press in some markets. The move would have put Scarborough and Gregory in direct competition for guests and provided the MSNBC host with a springboard to take over Gregory’s show. NBC declined to have Scarborough comment; in a July tweet, he denied having angled for the job.

Todd’s Meet the Press ambitions made for tension. “It was obvious that Chuck knew a lot more about politics than David did, and so that was uncomfortable,” says a person familiar with their relationship. “And then on Chuck’s end, David had the job he wanted, so that’s uncomfortable.”

Earlier this year, Sures, Todd’s agent, approached the NBC brass in New York, according to a former senior NBC executive, and demanded that Todd be handed Gregory’s job.

“They were very aggressive with the new NBC News leadership,” the former executive says, “and told them that if Chuck didn’t get Meet the Press soon, he was going to leave.” Sures denies this, and NBC declined to make Todd available.

• • •

Under the harsh glare of the press, Gregory’s relationship with Turness crumbled. She told colleagues that the show’s guest lineup still lacked ambition and creativity, and she took more control of the program. Sometimes on Fridays, she would contact the staff to say that the guests booked for Sunday weren’t suitable, forcing Gregory’s team to scramble to find replacements, according to people close to him.

Some were convinced Gregory was still distracted. In the spring, when NBC remodeled the Meet the Press offices, Gregory went on a shopping spree, according to a person familiar with the transaction. Just as the program was in chaos and his job was on the line, he redecorated with a new glass desk, an Hermès leather box, and other extravagant items totaling thousands of dollars, according to the source. A person close to Gregory denies he bought an Hermès box, “as good of a tale as that might be.” The source also says that Gregory worked his contacts hard, particularly when the ratings were struggling, and noted that he personally booked exclusive interviews with Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel and Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson in the first half of 2014.

By late July, NBC had made up its mind, according to people familiar with these discussions. The show’s ratings remained awful, and all the negative press was hurting the brand. Gregory had to go.

But NBC was so worried about more leaks that executives kept the decision a secret from everyone—including Gregory—while they began gaming out a replacement.

Turness looked at candidates inside and outside the network and considered choices both conventional and unconventional. She even met with Jon Stewart, host of Comedy Central’s wildly successful Daily Show, who could have brought with him legions of young viewers and embodied the transformation Turness was hired to engineer. “I’m sure part of them was thinking, ‘Why don’t we just make it a variety show?’ ” Stewart told Rolling Stone.

Turness’s secret didn’t last long. Page Six at the New York Post soon declared: “David Gregory’s time on Meet the Press is almost up.”

This time, when Gregory asked NBC to stick up for him, he didn’t get the response he expected. Instead, the network told his agent the bad news: He was out. Now it just needed to figure out how much the separation was going to cost.

After several days of negotiations, Gregory and NBC still couldn’t agree on their final terms. That’s when Gregory found himself driving through the New Hampshire mountains, suffering one final embarrassment as host of Meet the Press.

As news of his ouster blasted around the internet, Gregory’s phone lit up. Matt Lauer, Secretary of State John Kerry, and JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon called to say how sorry they were, according to a source close to Gregory. And that’s not all. The source says the corporation’s most senior executives—including NBC Universal CEO Steve Burke and Comcast CEO Brian Roberts—called, one by one, to express their regret for how his departure was handled.

“I had a great run hosting Meet the Press,” Gregory said in an e-mail to Washingtonian. His $4-million severance agreement prevents him from discussing the split. “I loved doing it and I am proud of the work we did.”

Only one year after arriving at NBC with plans to overhaul the news division, Turness tossed her ambitions aside and made the safest choice possible. In the end, she installed Chuck Todd, the ultimate incarnation of Washington’s talking-head establishment.

On Sunday, September 7, a slimmed-down and newly tanned Todd interviewed President Obama for his first show as moderator. The program attracted its largest audience in six months, earning NBC a hard-fought ratings win. The following week, Meet the Press fell back to third place. It hasn’t returned to the top since.

Senior writer Luke Mullins can be reached at lmullins@washingtonian.com

This article appears in the January 2015 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)