Jeffrey Goldberg is a natural and irrepressible funnyman. Drop

a name, a topic into the conversation and the deadpan ripostes are

immediate and unceasing.

On his editor at the Atlantic, James Bennet,

known for being taciturn: “A man of many words.”

On dropping out of the University of Pennsylvania in the

mid-1980s: “I’m on an extended leave of absence.”

On how he would describe his (somewhat heavyset) physical

appearance: “You mean fat?” A first stab: “Omar Sharifian.” A second, more

realistic attempt: “Somewhere between Polish peasant and Wisconsin dairy

farmer.”

On the slight Long Island accent detectable in his voice: “Are

you calling me Jewish?”

Well, yes. But the word comes to mind not because of his

accent, and not even because Goldberg is, ethnically and religiously,

Jewish. It’s because Goldberg, as a matter of personal and professional

identity, is proudly and insistently Jewish. This is, after all, a fellow

who used to hang a paper on his office door at the Atlantic with

the words the misunderstood jew, a sly reference to what certain

irreverent wags call Jesus.

“I think journalism is a very Jewish profession,” he says in a

podcast, “Life as a Jewish Journalist,” recorded for the Partnership for

Jewish Life & Learning. “Jews are very interesting. I think pound for

pound we are the most interesting people in the world. There’s 12 million

of us, and we make so much noise. And we’re so controversial and everybody

is in everything and it’s absolutely fascinating. What’s the famous

expression? We’re like everyone else but more so.”

It has been a long, hard climb, but Goldberg, who is nothing if

not noisy, has made himself the most influential journalist in

Washington—indeed in America—writing on Israel and the broader Middle

East. Nobody gets bigger “gets” when it comes to newsmaking interviews—he

has scored exclusives with both President Obama and Israeli prime minister

Benjamin Netanyahu. Goldberg’s frequent pronouncements on whether Israel

will attack Iran to keep the mullahs from obtaining a nuclear bomb are

tracked at the White House and beyond. His reportage and commentary on

such subjects are everywhere—in long pieces for the Atlantic; in

Goldblog, his Atlantic.com blog; in a regular column for the opinion site

Bloomberg View; and on news shows such as Meet the

Press.

“In terms of people who really specialize in the Middle East,

Jeff probably is in a class by himself,” says David Rothkopf, a close

friend of Goldberg’s who is CEO of the FP Group, publisher of Foreign

Policy magazine.

Goldberg’s influence derives in part from the perception that

he has many close sources in Israel, where he’s well known and generally

esteemed by decision makers. He moved there in his twenties, becoming an

Israeli citizen (while retaining his American citizenship) and serving a

stint in the military.

“He has put himself at risk for his beliefs” in the Jewish

state, and that makes him one of a kind—“sui generis”—among Washington

journalists, says Michael Oren, the American-born Israeli ambassador to

the United States.

Oren, too, is a good friend of Goldberg’s. “We just schmooze

about things,” the ambassador says, especially when “I need a good laugh.”

Goldberg, he notes, has a gift for attracting friends by being

“exceedingly, almost excruciatingly funny.”

Another friend is David Gregory, host of Meet the

Press. Goldberg and Gregory are part of an informal Jewish-studies

group that includes other Goldberg buddies such as Franklin Foer, editor

of the New Republic; David Brooks, the New York Times

columnist; and Martin Indyk, a former US ambassador to Israel.

Goldberg is not only hilarious but also warm-hearted—“an

exceptionally menschy guy” who “enjoys playing a rabbinic role” as a

counselor to his friends, says Foer, who consulted Goldberg last year

while debating whether to return to the editor’s seat at the New

Republic.

Bennet, Goldberg’s Atlantic editor, is an old friend

whom Goldberg helped show the ropes years ago when Bennet became Jerusalem

bureau chief for the New York Times. (Goldberg was offered the

job to succeed Bennet but turned it down, in part for family reasons, he

says.) And the Atlantic’s owner, David Bradley, swears unending

devotion: “If Jeff ever leaves me, I will be wherever Jeff

goes.”

Bradley wooed Goldberg to the Atlantic by sending

ponies to Goldberg’s home in DC’s American University Park neighborhood

for his three young children to ride in their back yard. (The family has

since moved to the District’s Forest Hills.) It took Goldberg a few years

to make up his mind, but in 2007 he finally left the New Yorker,

where he was a staff writer. Goldberg’s wife, Pamela, proved the key. “She

and I effectively decided, and then she told Jeff,” Bradley

says.

Goldberg, in turn, has played to Bradley’s admitted appetite

for “journalism tourism.” Last May, at Goldberg’s invitation, Bradley

joined him for a trip to the Middle East highlighted by a luncheon

interview with King Abdullah II of Jordan and a sit-down with Prime

Minister Netanyahu of Israel. (A lowlight was watching Netanyahu and an

aide fumble trying to get a remote control to turn on a wall-unit air

conditioner. “And this is the country that is going to stop the Iranian

nuclear project,” Goldberg stage-whispered to Bradley.) It’s remarkable,

Bradley says, how well Goldberg knows all the top players.

“I love David Bradley,” Goldberg returns in kind. “He’s a

gentleman, a deeply moral person.” Besides, Goldberg says, unable to

resist, “some of my best friends are gentiles.”

• • •

Yet even with all these important friendships—and many

more—Goldberg is chronically embroiled in disputes. He’s quite possibly

Washington’s most polarizing journalist—no easy feat. “You write about the

Middle East, you’re just going to get it in the neck,” he says. “The

emotions run so hot, the stakes are so high, and the various hatreds are

so deep.”

In part, Goldberg generates heat because of his background—in

particular, his past service in the Israeli Defense Forces as a military

policeman at a prison housing Palestinians arrested in an uprising against

Israel. Although he can be quite critical of Israel, his reflex is to take

its side when Israeli lives are on the line.

“The media is biased against Israel,” he declared in a blog

post in November as Hamas fired rockets at Israeli cities while the

Israeli Air Force targeted Hamas sites in the crowded Gaza Strip. With his

prominent media platforms and his resolute support for the primacy of the

US/Israel friendship, he’s a lightning rod for anti-Zionists as well as

for out-and-out haters of Jews.

Much of his unsolicited e-mail is anti-Semitic, he says: “You

can always tell the real Nazis because they can’t spell.”

But it’s also true that Goldberg has a gift for generating

controversy. He’s naturally contentious, like the onetime king of

Washington polemicists, Christopher Hitchens, who died a year ago.

“Hitchens loved to fight all the time,” Goldberg says. “I can’t fight all

the time.” Maybe not, but he does have prodigious energy for

conflict.

He stirs controversy partly because of his effort to play a

role as a kind of umpire on sensitive matters involving Jewish politics

and culture. One aspect of this self-appointed office is to determine

which players and US policies can be deemed genuinely in Israel’s favor.

Goldberg acts as “the keeper” of “the admission gate to the pro-Israel

tent,” says Jeremy Ben-Ami, head of J Street, a left-of-center pro-Israel

group in Washington.

At first, Goldberg was reluctant to admit J Street, founded in

2008, to the tent, but after some sniffing and baring of teeth on

Goldblog, he opened the flap and helped legitimate a role for the

organization in the Israel debate as a competitor to the right-leaning

American Israel Public Affairs Committee, known as AIPAC and generally

considered the most powerful pro-Israel group in Washington. In his 2011

book, A New Voice for Israel, Ben-Ami wrote that in 2009 Goldberg

subjected him to “kind of an interrogation to determine if I passed

pro-Israel muster according to Goldberg’s moderate brand of Israel

boosterism.”

Goldberg supports an Israeli/Palestinian pact to establish an

independent Palestinian state, with East Jerusalem as its capital. He

doesn’t want to see Israel’s founding ideal as a democratic Jewish state

undermined by permanent rule of a Palestinian population that could become

a majority in a “Greater Israel” if current demographic trends

continue.

That position puts him to the left of pro-Israel hawks who

believe that all of Jerusalem should remain in Israel’s hands and who

favor expanding Israel’s already extensive settlements on the West

Bank—the heart of any future Palestinian state. At the same time, Goldberg

is to the right of Israel critics who support tactics such as boycotting

products made by Jewish West Bank settlers.

Ben-Ami more or less accepts Goldberg as a gatekeeper, but

others bridle at what’s viewed as a heavy-handed attempt to police the

discourse. There’s Goldberg’s penchant, for example, for calling out

prominent people—including bigwig journalists—for, as he sees it,

scapegoating Jews or using anti-Semitic tropes. Maureen Dowd received this

treatment for a New York Times column in September in which she

referred to an adviser to Mitt Romney as a “neocon puppet master.” (The

adviser, Dan Senor, is Jewish, although Dowd didn’t mention

that.)

Dowd’s column was published on the eve of Rosh Hashanah, the

Jewish New Year, and Goldberg titled his blog post happy new year, puppet

masters. “Maureen may not know this, but she is peddling an old

stereotype, that gentile leaders are dolts unable to resist the

machinations and manipulations of clever and snake-like Jews,” he wrote.

James Fallows, whose office is next to Goldberg’s at the Atlantic,

sped to Dowd’s defense. MAUREEN DOWD IS NOT AN ANTI-SEMITE, Fallows

wrote in the headline to a post on his own Atlantic blog.

“My basic theory of life places a lower emphasis on what are

essentially tribal loyalties than Jeff’s does,” Fallows told me a few

weeks after the dustup.

“I love Maureen,” Goldberg says. “I was just taken aback [by

the column]. I read it, I reacted, I wrote about it.”

Invited to comment on Goldberg’s remarks, Dowd replied by

e-mail: “Nah.”

But Goldberg can be more forgiving. In a Bloomberg View column

in early January on the question of whether President Obama’s nominee for

Defense Secretary, Chuck Hagel, was anti-Semitic, as suggested by some

critics, Goldberg declared: “The short answer is no. The long answer is

also no. Which is not to say that Hagel will soon win the American Jewish

Committee’s Man of the Year Award.” He noted that some of Hagel’s views on

Iran and Israel were shared by “left of center” Israeli

politicians.

A frequent Goldberg target is his former Atlantic

colleague Andrew Sullivan—a friend with whom he’s perpetually fighting and

making up. Sullivan, who runs the blog the Dish, credits Goldberg with

making him understand how important it was to the peace process for Israel

to stop building settlements on the West Bank.

But Sullivan has since become an increasingly vocal critic of

Netanyahu’s government for failing to confront the settlers and make peace

with the Palestinians—a posture that in Goldberg’s view amounts to a

blame-the-Jews mindset. “He thinks I’m a terrible Netanyahu apologist, and

I think he’s a scapegoater of Jews,” Goldberg wrote of Sullivan on

Goldblog in March.

When I call Sullivan, he starts by ladling praise on Goldberg:

“An absolutely delightful and sweet human being. I love the guy.” Then he

slices and dices, accusing Goldberg of reverting to “foul” tactics, aiming

to control the public conversation on Israel and consigning to the

sidelines non-Jews like Sullivan who have a less accepting line on

Israel.

“Jeffrey really believes that there is a high-priest caste of

journalists at a certain elite level, whose job it is to tell people what

they need to know,” Sullivan says. “That is not being a journalist—that is

being an operator.”

What’s more, he adds, Goldberg “is a Jewish journalist before

he is a journalist.” What Sullivan, who is Catholic, seems to feel

exasperated by is that Goldberg is so unrelenting in asserting a Jewish

identity. Sullivan recalls the misunderstood jew phrase on Goldberg’s door

at the Atlantic: “You can’t even walk into his office without

seeing ‘Jew.’”

As he often does when hearing criticism of his perspective on

Israel, Goldberg says detractors tend to have a simplistic view of an

inherently complex situation. Sullivan, Goldberg says, has flipped from a

“brittle” worldview that was “hyper-pro-Israel” to an “equally brittle”

perspective that “Israel is the devil.”

“He’s trying to police me,” Goldberg says of Sullivan, “who, by

the way, I love.”

• • •

Goldberg was born in Brooklyn in 1965 and grew up on the South

Shore of Long Island, in Malverne, described as a “tribally Catholic,

deeply American town” in his 2006 book, Prisoners. (The book

focuses on his time living in Israel.) “I knew well that Jews were

disliked—I knew this in an uncomfortably personal way,” he wrote of his

childhood. “I didn’t like the dog’s life of the Diaspora. We were a

whipped and boneless people.”

When I meet with him at the Watergate, where the

Atlantic’s offices are located, Goldberg elaborates on the

bullying treatment meted out to him decades ago. He says he was “jumped”

in middle school by “a bunch of little Irish pogromists.” (And “I remember

their names.”) At first he retreated to the library, but eventually he

fought back: “It was the black kids who taught me how to

fight.”

“One of the ways you can create Jewish consciousness,

obviously, is by not being around Jews,” he says. “And somehow my parents

managed to find the one spot on Long Island that was free of

Jews.”

He harbored dreams, nurtured by an experience at a socialist

Zionist summer camp in the Catskills, of being a farmer in Israel. But

once he was in Israel, his actual life there—which began as a grunt-level

agricultural worker on a kibbutz—dispelled those illusions.

“We get the Arabs to clean up the shit” at the chick-en house,

an Israeli foreman told him, as he recounts in Prisoners. “That’s

why we have Arabs.” (Full disclosure: As a Member of the Tribe—an M.O.T.

in Goldblogian vernacular—I performed volunteer duty a few years earlier

at the same chicken shack on the kibbutz, Mishmar Ha Emek, where Goldberg

lived. Also, I formerly was a staff writer at Atlantic Media, owner of the

Atlantic, and have written for that magazine.)

Israeli Army training was more to his liking: “I was

exceedingly happy—the rifle was electric with the promise of Jewish

power,” he writes. But again, the reality of his service as a policeman at

Ketziot, a large prison in the Negev desert, proved an affront to his

Americanized liberal sensibility. “You can’t beat them enough,” one of his

Israeli colleagues said of the Palestinian inmates. (Goldberg’s initial

hope was for a career in a branch of Israeli intelligence, but he writes

that he found out he “would never attain the topmost security clearances”

because of his American upbringing.)

After fulfilling his military obligation, Goldberg worked as a

humor columnist for the Jerusalem Post. But his heart was no

longer in a life in Israel. “In Israel, I discovered just how American I

am,” he says, “and I decided to make my life here, where I’m from. I’m

just dispositionally American, patriotically American.” He says he has

decided to give up his Israeli citizenship.

“If Israel goes much further down the road I think it’s on and

becomes more of a theocratic, totalitarian-style state,” he asks, “how

could the liberal-minded American Jew support that?”

It’s a stark question. “Clearly Jeff is still struggling” with

long-held, conflicting feelings about Israel, says Israeli ambassador

Oren, and “that to me is one of the most admirable things about him—that

he is struggling.” Oren adds: “Others have made up their mind” that Israel

“can do no right.”

Goldberg’s Zionism remains intact, though. It represents his

conviction in the necessity of a permanent Jewish homeland as a refuge for

Jews. “I care about the continuity of the Jewish people,” he says. “If

Israel had existed in 1939, there would not have been a

Holocaust.”

Goldberg is a congregant at Adas Israel in DC’s Cleveland Park,

but he isn’t strictly allegiant to Jewish observance or custom, such as

dietary law, confessing, “I eat shellfish between Memorial Day and Labor

Day if I’m within sight of a large body of water.”

• • •

Washington, with its manifold opportunities for a journalist of

Goldberg’s interests and talents, has long been a magnet to him. After

dropping out of Penn in the mid-1980s and before moving to Israel, he

worked as a Washington Post police reporter. Post

business reporter Malcolm Gladwell—soon to be a superstar at the New

Yorker—shared an apartment with Goldberg in DC’s Mount Pleasant

neighborhood and, as Goldberg recalls, “introduced me to the woman who

would become my wife by telling me that he met the woman who would become

my wife.”

But Goldberg’s ascent to his current station as Washington’s

go-to journalist on Israel and the Middle East hasn’t been without bumps.

An example—underscoring the perils and jealousies of journalistic life

here—is his dramatically shifting relationship with Leon Wieseltier,

longtime literary editor of the New Republic.

For years, Wieseltier—a kind of philosopher-king with long

white hair and a daunting pedigree as a student of Jewish history at

Harvard, a member of that university’s august Society of Fellows for

“persons of exceptional ability,” and a reader of the Talmud in

Aramaic—has mentored promising young journalists aiming to establish a

name as commentators on Israel and related themes. Wieseltier and Goldberg

inevitably found each other, and at first admiration was mutual. In

Prisoners, Goldberg thanks Wieseltier for his “learned counsel,”

and Wieseltier praises Goldberg, in a blurb on the same book, for his

“vivacious candor.”

In 2007, Wieseltier invited Goldberg to review The Israel

Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy, a controversial book by John J.

Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt arguing that America’s misguided embrace

of Israel was due to the influence of powerful, pro-Israel pressure groups

in Washington. Goldberg responded with a 7,000-word article, the usual

suspect, that appeared on the New Republic’s cover. The review

called The Israel Lobby “the most sustained attack, the most

mainstream attack, against the political enfranchisement of American Jews

since the era of Father Coughlin.” Wieseltier recalls that he gave

Goldberg the book to “demolish” it, and “he did demolish it.”

But over the past year, a rift has developed between the two.

Wieseltier is taking barbed aim at his protégé, as in criticism of

Goldberg’s contribution to a recently published version of the Haggadah,

the book of prayer and commentary used by Jews at the Passover Seder. “His

comments are delivered in the tone of noisy worldliness, of tough-guy

sentimentality, that marks all his writing. His reliance on cliché is

considerable,” Wieseltier wrote of Goldberg in the spring 2012 edition of

the Jewish Review of Books, adding that Goldberg “knows more

about politics than he knows about Judaism.” (The Haggadah, titled New

American Haggadah, is edited by the writer Jonathan Safran Foer,

brother of New Republic editor Frank Foer.)

Wieseltier’s dig at Goldberg rippled through the overlapping

circles in which the two men move. When I call Wieseltier, he intensifies

his disparagement of Goldberg. “He badgers people in what he writes,” he

says. “He can be haughty, and he can be bullying. What he most aspires to

be is a big shot—capital B and capital S.”

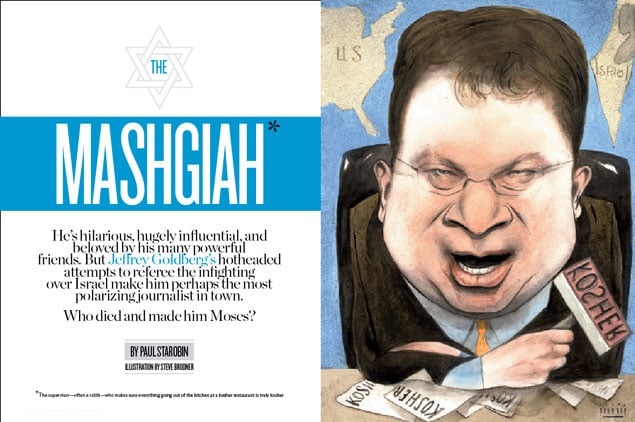

He sees Goldberg not as gatekeeper to the pro-Israel tent but

as a would-be, journalistic equivalent of the mashgiah. That’s the Hebrew

word for the supervisor—a rabbi or someone else of impeccable

credentials—who makes sure everything going out of the kitchen at a kosher

restaurant is truly kosher. “Goldberg is a little bit in the business of

deciding who is kosher and who is not,” Wieseltier says. The problem, he

explains, is that Goldberg fails to qualify for the role: “He’s a blogger.

He’s not an analyst, he’s not a scholar.”

Such comments are wounding to Goldberg if only because of

Wieseltier’s generally conceded brilliance. “Leon is one of the world’s

smartest people,” says the Jewish scholar Erica Brown, who works for the

Jewish Federation of Greater Washington and leads the Jewish study group

in which Goldberg and several of his friends are members.

Still, as Goldberg partisans see it, this is a case of an

insecure and spiteful Wieseltier turning on an acolyte who threatens

Wieseltier’s own standing as a mashgiah. “There’s a lot of

big-Jew-on-campus competition out there,” says a journalist friend of

Goldberg’s.

Even Andrew Sullivan has sympathy for Goldberg’s plight.

“Leon’s opposition to Jeffrey controlling the debate is that Leon should

control the debate,” Sullivan—who has a long history of venomous clashes

with Wieseltier—says with a hearty laugh.

Goldberg, characteristically, has a zinger for his former

mentor: “I’d rather be mashgiah than the Malach Ha Mavet”—Hebrew for angel

of death. “If I had two phone numbers in my phone and I was in serious

trouble, and one was Leon’s and one was Andrew’s, I would go with Andrew

in a heartbeat. And yet Leon and I are obviously closer

ideologically.”

• • •

Trouble for Goldberg most frequently arises from hot-tempered

posts on Goldblog. He credits Sullivan (“I watched Andrew for years”) for

showing how blogging could be done successfully and has described Goldblog

as an “organic extension” of himself and his interests—although it’s

perhaps better thought of as a branch of his id. “He cares passionately

about the things he cares passionately about,” says Frank Foer. “With

blogging, he can be pugnacious because he cares.”

But another friend, New Yorker editor David Remnick,

has encouraged Goldberg to give up the blog. “I would like to see him

write more long pieces,” Remnick says, to showcase Goldberg’s talents as a

magazine writer.

Part of the problem is that Goldberg—once the quarry of

schoolyard bullies—has displayed a taste for punching at targets well

below his weight, and in a no-holds-barred, ad hominem fashion. For

example, he went after the not particularly well-known journalist Allison

Benedikt for an article she wrote for the Awl, an online magazine. The

piece was about Benedikt’s disillusionment, as an American Jew, with

Israel—specifically about how she felt “sick” about a recent trip, with

her non-Jewish husband, to an Israel that felt like a war

zone.

In one post, Goldberg castigated her for her “stunning lack of

curiosity” as to why Israel is besieged and attacked her “dickish husband”

(who likewise blasted Goldberg in a tweet). The battering seemed so out of

proportion to the offense that Goldberg pulled back, quoting a reader who

had been following the episode: “Jeffrey, do you also like to kill little

puppies for fun? Leave this girl alone.”

And yet, as Goldberg noted on his blog, about 60 percent of his

mail was running in support of his assault on Benedikt. “Here’s the real

psychosis,” says a Jewish journalist who knows Goldberg but asked not to

be quoted by name for fear of his ire. “At some level, American Jews want

that level of aggression in a spokesman” because of their history of

oppression. And Goldberg “gets pleasure out of torturing

people.”

Even when Goldberg is pursuing weightier figures, he can do so

in a sophomoric style. In Goldblog, Harvard professor Stephen Walt,

coauthor of The Israel Lobby, is baited as “Stevie.” Goldberg

ramped up his campaign against Walt by calling out Washington

Post-owned Foreign Policy, where Walt is a blogger, “for

hosting a Jew-baiting blog,” as he told a reporter for Tablet, an online

Jewish magazine.

Walt says he feels outraged by “this vile smear tactic” that

“has made me somewhat radioactive in policy circles.” Foreign

Policy CEO David Rothkopf says that in this instance Goldberg went

too far. “It’s certainly not a Jew-baiting blog,” Rothkopf, son of a

Holocaust survivor, says of Walt’s FP blog.

Goldberg’s fulminations have contributed to stresses and

strains at the Atlantic—a publication founded by Boston Brahmins

in the mid-19th century and not known for verbal fisticuffs.

Tensions ratcheted up last March upon publication of a book

much anticipated by followers of Israel: The Crisis of Zionism by

Peter Beinart, a former New Republic editor. Beinart called for a

boycott of products produced by Jewish settlers as a means to pressure

Israel to get out of the West Bank.

Goldberg rejected the boycott idea “because I find economic

warfare targeting Jews so distasteful, for obvious historical reasons,” he

said on Goldblog. “And to be completely blunt,” he added, “I’m not that

interested in debating Peter’s new book, which I’ve just finished reading,

because I find his recounting of recent Middle East history one-sided and

filled with errors and omissions. The Middle East crisis is complicated,

except in Peter’s telling.” As for the errors and omissions, Goldberg

didn’t cite any.

Hours later, Robert Wright, a senior editor at the

Atlantic, weighed in on his own blog: “With Peter Beinart’s book

The Crisis of Zionism only days away from publication, the

attempt to marginalize Beinart has begun.” Wright and Goldberg had clashed

before: In Wright’s pre-Atlantic days, Goldberg had branded

Wright, in a Goldblog headline, as a “genocide denier” for allegedly

saying that the Kurds were not victims of genocide at the hands of Saddam

Hussein. Wright, who vehemently disputes Goldberg’s accusation, declined

to comment for this story.

Andrew Sullivan jumped in on his Daily Beast blog with harsh

criticism of Goldberg’s dismissal of Beinart’s book. On Goldblog, Goldberg

shot back: “As we’ve learned over time here at the Atlantic,

there’s no arguing with the guy.” Outraged that Goldberg was now claiming

to speak for the Atlantic, Sullivan complained directly to

Bennet. Goldberg then changed his blog post to make it clear he was

speaking only for himself.

Whew.

Bennet and Goldberg offer a contrast of type—Bennet is cool,

reserved, and laconic, while Goldberg is excitable, disarmingly frank, and

voluble—and the juxtaposition seems to amuse them both.

In Bennet’s corner office at the Watergate, we chat about

Goldberg. “I can imagine he’s a lot to handle,” I say.

Bennet laughs: “You can, huh?” He offers no argument to the

proposition that Goldberg sometimes falls short of the Atlantic’s

standards of editorial fairness—such as when Goldberg dismissed Beinart’s

book as “filled with errors and omissions” without listing any. Bennet

agrees: “If you’re going to call somebody out, you should be able to back

it up.”

At the same time, Bennet disputes the notion that Goldberg

tries to police the discourse on Israel—as does Goldberg himself. All such

commenters, including Leon Wieseltier, Bennet says, are only expressing

their opinions. If Goldberg “has more credibility and more authority, it’s

because he has more credibility and authority, and he’s earned that,”

Bennet says. “The test is the body of work. I would put Jeff’s body of

work on the subject of Israel, the broader Middle East, and Iran up

against anybody, certainly in this country—actually anywhere.” Bennet,

whose mother is a Holocaust survivor, can appreciate the intensity of

Goldberg’s commitment to the survival of the Jewish people.

Bennet makes a good point about Goldberg’s having earned his

authority. It’s fair to note, as Wieseltier acidly does, that Goldberg

isn’t a scholar of Jewish history or of the Jewish spiritual and

philosophical traditions. But it’s also true that Goldberg has personally

immersed himself in the cauldron of the Middle East and has thus acquired

a street-level knowledge of the region superior to Wieseltier’s—and for

that matter Sullivan’s and possibly anyone else’s in

Washington.

For a prescient piece for the New York Times Magazine,

published a year before the 9/11 attacks, Goldberg managed to enroll

himself in a Pakistani madrassah at which a next generation of jihadists

was being groomed. “The only enemy Islam and Christianity have is the

Jews,” the master of the religious school tells him in greeting, to which

Goldberg responds, “I’m Jewish.” There is “a moment’s pause,” and the

master says, “Well, you are most welcome here.” A pair of 11-year-old boys

take to hiding behind trees and surprising him with shrieks of

“Osama!”

Goldberg journeyed to the Kurdish lands of Saddam Hussein’s

Iraq; he once was held hostage by gun-toting Palestinian militants in

Gaza. He could have ended up a Daniel Pearl, the Wall Street Journal

correspondent kidnapped in Karachi in 2002 and beheaded by Islamic

fanatics who released a graphic video of the “slaughter” of a

“Jew.”

“There is a kind of courageous exposure of self” in Goldberg’s

insistence that he’s a Jewish journalist, says an old friend, Jonathan

Rosen, an editor for whom Goldberg wrote back in the 1990s at the

Forward, the New York City-based Jewish newspaper. “It can look like

a natural path to prominence,” Rosen says. “But there are many Jewish

journalists uncomfortable writing about these things. You have to be

willing to brave that proclamation of identity. That’s as dangerous as

walking around the madrassahs of Pakistan.”

Goldberg, who told me he erred in his treatment of Beinart’s

book, takes criticisms offered by his friends to heart. “He’s right,” he

says of Remnick’s point about how his time might be better spent on

long-form articles. “Blogging is in many ways a disaster for journalists,”

Goldberg says, noting that “it’s all glandular.” At the very least, he’d

like to moderate his style. “I used to be hotter. Now I’m trying to be

cooler,” he says, sounding as if he means it.

• • •

Goldberg is mischaracterized, probably willfully, by some of

his fault-finders. A staple reproach is that he’s Benjamin Netanyahu’s

“faithful stenographer,” as Roger Cohen asserted in a 2009 New York

Times column. That perception is sufficiently ingrained in Washington

that Barack Obama himself directed a jest of this sort at Goldberg at an

off-the-record meeting in May at the White House with a crew of

foreign-policy journalists.

When a question about a policy position of Netanyahu’s

government was raised, Obama turned to Goldberg and said, according to a

leaked version of events confirmed by several participants, “You should

ask Jeff. He knows a lot more about this stuff than I do.” Goldberg played

along. “I’m not authorized to talk about that,” he said, one-upping the

President in the kidding-around department.

But Goldberg does pan Netanyahu at times. BIBI: THE MIDDLE

EAST’S WILE E. COYOTE was the headline on Goldblog for a post about

Netanyahu’s speech in September at the United Nations, when Israel’s prime

minister displayed a “cartoonish drawing,” as Goldberg called it, of an

Iranian nuclear bomb. “He insulted the intelligence of his audience” and

“people are laughing at him,” Goldberg declared.

From pro-Israel voices to the right of Goldberg comes the

complaint of “diligent cheerleading” for Obama, as made by Jonathan Tobin

in Commentary. Goldberg does seem to have a soft spot for Obama,

who is reviled by conservative opponents in the US for a supposedly

anti-Israel bias and isn’t especially well liked in Israel itself. Citing

Obama’s “many Jewish mentors, colleagues, and friends,” Goldberg has

praised him on his blog as “the most Jewish president we’ve ever had

(except for Rutherford B. Hayes).”

But Goldberg isn’t a cheerleader. “Obama’s record in the Middle

East suggests that missed opportunities are becoming a White House

specialty,” he wrote in an October Bloomberg View column. “Perhaps Obama

isn’t quite the brilliant foreign-policy strategist his campaign tells us

he is.”

Nor is Goldberg a “neocon,” as he’s been called by Andrew

Sullivan and others. He did support George W. Bush’s war in Iraq—but not

for the standard neocon reason of spreading democracy. Goldberg’s

perspective on the Middle East tends to emphasize its tragic elements.

“Saddam Hussein is uniquely evil, the only ruler in power today—and the

first one since Hitler—to commit chemical genocide,” against the Kurds,

Goldberg wrote in Slate in 2002, before the war. “Is that enough of a

reason to remove him from power? I would say yes, if ‘never again’ is in

fact actually to mean ‘never again.’ ”

Never again. No other phrase packs more power in the

modern Jewish lexicon. Six million Jews died in the Holocaust, and that

was only 70 years ago—not long at all in historical time. Goldberg is

perhaps best understood as a “never again” journalist. IS IT POSSIBLE TO

THINK TOO MUCH ABOUT THE HOLOCAUST?, a Goldblog headline asked. His reply:

“No, the answer is no—it is not possible to think about the Holocaust too

much.”

This mindset helps account for Goldberg’s fixation on whether

Israel will launch an air strike against Iran’s nuclear facilities. That

country’s president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, has vowed to “wipe the Zionist

entity off the map” and has referred to Israel as a “black and dirty

microbe.”

“I see it as the foremost immediate American foreign-policy

challenge,” Goldberg told me of the Iranian nuclear threat, “and I see it

as the biggest challenge to Israel’s existence.”

That may be right on both counts. But in forecasting, on

multiple occasions, a high degree of likelihood of an Israeli air strike

(which he doesn’t necessarily consider a good idea), Goldberg has

exhibited a degree of certainty that perhaps no outsider can

possess.

In a much-debated Atlantic cover story in September

2010, the point of no return, he reported “a consensus” of Israeli

decision makers and others who believe “that there is a better than

50-percent chance that Israel will launch a strike by next July.” What

Goldberg didn’t know was that at the time he was reporting the likelihood

of an air strike, there was a top-secret US/Israeli initiative, known as

Stuxnet, to attack Iran’s nuclear facilities by means of a

cyberworm.

It’s conceivable that he was deliberately misled by Israeli

policymakers. Or it might be that he placed too much confidence in his

reporting. His most unforgiving critics suggest that he was willing to be

used by Israel to present the bluff in the pages of the Atlantic.

In any case, the story wasn’t quite on target, as conceded even by a

Goldberg admirer, Dennis Ross, the veteran diplomat who at the time of

publication was President Obama’s chief adviser on Middle East issues. “He

drew a conclusion in terms of timing that I thought was overstated,” Ross

says.

“He’s a journalist” who is “not privy” to state secrets in

Israel, Israeli ambassador Oren says in defense of Goldberg, so he can

only do his best to interpret the incomplete information he

has.

But that seemingly chastening experience didn’t stop Goldberg

from writing in his Bloomberg View column last March that “I’m highly

confident that Netanyahu isn’t bluffing—that he is in fact counting down

to the day when he will authorize a strike against a half-dozen or more

Iranian nuclear sites” and still again to predict in his column in July

that Israeli leaders “may very well decide” to launch a strike before the

American election on November 6.

Nope and nope. It could be that the only thing off is his

timing. But he risks sounding like a broken record.

• • •

Philosopher Isaiah Berlin famously divided humankind into

hedgehogs, who know one big thing, and foxes, who know many little things.

In these terms, Goldberg “is clearly a hedgehog,” says his friend Walter

Isaacson, an author and the president of the Aspen Institute. (With his

varied biographies of Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein, and Benjamin Franklin,

Isaacson sees himself as all fox.)

Goldberg, though, pushes back against the hedgehog designation,

and he has a good case. Years ago, he covered the Mafia for New

York magazine. Last summer, he wrote a long article for the

Atlantic, jersey boys, about New Jersey governor Chris Christie’s

eternal love for Bruce Springsteen—and Goldberg’s own. “If the E Street

Band at full throttle doesn’t fill you with joy, you’re probably dead,” he

wrote. And one of his best pieces ever was a globetrotting 16,000-word

opus for the New Yorker on a pair of American elephant

conservationists gone amok. In a riveting narrative that shifted from

Zambia to Idaho, Goldberg more or less solved a murder

mystery.

Nor are his literary tastes as predictable as you might think.

He’s fond of the poetry of T.S. Eliot, he says, even though “Eliot didn’t

like Jews.”

It may be, Goldberg suggests, that he’s a hedgehog in having to

meet an “expectations trap” of his own design for what he’s supposed to

write about. He feels he has in a way led his core readers to expect him

to focus tightly on Israel and the Middle East—and now feels bound to

fulfill that self-imposed obligation.

“The only joy in journalism for me is the stories that have

nothing to do with this,” he says of his specialty in Israel and the

Middle East. “There’s no joy in writing about the Middle East. It’s not a

joyful place.” The subject “is too fraught for me—it’s too serious, too

consequential.”

Beneath the torrent of ready jests is angst that events in the

bloody patch of the planet he covers could get a lot worse. The God of the

Jews is a God who can perform miracles to alter the course of history—as

in parting the Red Sea to let the Israelites escape from bondage in

Egypt—but Goldberg, even though he’s a believer, isn’t expecting any such

feats in today’s time.

“Do I believe in God? Yes, I believe in God,” he says. “I think

he’s busy doing something else right now.”

This article appears in the February 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.