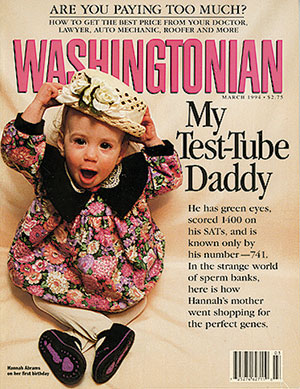

Nineteen years ago, my daughter, Hannah, appeared on the cover of this magazine.

The photograph was taken just after her first birthday. It shows her in a fussy Laura Ashley dress, bought by a stylist who shunned the overalls and T-shirts on tiny hangers in Hannah’s closet. The photographer’s assistant stuck a girly hat on her head, and in the picture Hannah is in the process of removing it. Inside the issue is my admission that Hannah was the child of a single mother.

Today the idea of writing a cover story on becoming a single mother “by choice” sounds mildly ridiculous. But in 1994 it bordered on scandalous.

As soon as the story came out, my phone began ringing. Mostly it was women from around the country who were intrigued by the idea of using a sperm donor to become mothers. Sometimes it was media outlets wanting to visit our little house in North Arlington. Once it was a woman who was pregnant by the same donor I had used. Her son and my daughter have grown up calling each other half siblings.

But the article also made me a target. The conservative Family Research Council went on TV to denounce me as “tearing the fiber of American families.” I got hate mail and middle-of-the-night phone calls, including one from a man so angry it sounded like he was dry-heaving. He called me names I’d never heard before and said he prayed that my daughter and I would die a rather unusual and painful death.

I prefer to remember the nine women who told me they decided to use donor insemination or adopt after reading my article. I was in baby heaven, so when women asked me what it was like to be a single mom, I gushed, I bragged, I kvelled. Occasionally I urged them to consider the negative side of raising a child on their own, but mostly I told them how happy we were.

The first hint of trouble came when Hannah was four. We were driving somewhere and she was strapped in her car seat in the back of the minivan. “Mommy, I know who my daddy is,” she said.

Hannah and I had talked about how she was conceived and what a donor was, but I had never referred to him as a “daddy.” She was prone to announcing she had a mommy and a “doughnut.” So this was new.

“Who?” I asked.

“It’s Peter Pan!” she trilled. “He can’t come be with me because he’s in Never Never Land! He’s never going to grow up, and he’s always going to play with the Lost Boys.”

That described some of the men I’d dated, but I knew she was thinking more literally. I also realized she was creating a backstory to explain the absence in her life.

• • •

In the beginning, the story belonged to me.

I had moved here a year after graduating from Washington University in St. Louis. The next ten years were a blur of apartments, jobs, and relationships. It wasn’t until my early thirties that I turned into one of those cartoon drawings on a cocktail napkin: Oops! I forgot to have a baby.

A daytime talk show introduced me to the concept of sperm banks. I could find only three clinics in Washington that offered donor insemination, and one of them refused to treat single women. My gynecologist sent me to DC’s old Columbia Hospital for Women, where, after a psychological exam, I began trying to conceive. It took six months.

My friends and I would gather in the living room of my Capitol Hill condo to pore over my picks from the sperm bank. Glasses of wine in hand, we rejected the donor who listed his favorite food as tuna casserole. I couldn’t give that DNA to a child I would spend at least 18 years feeding. The forms were in the donors’ handwriting, so we would try to figure out what that looped “d” or slanted “j” said about each one’s character.

I’d chart my basal body temperature and head over to my doctor’s M Street office on insemination days, clutching a candle or framed photo of Mel Gibson. (That was before his anti-Semitic rants and drunken rages.) I bonded with my doctor and the nurse in charge of the insemination program. We laughed a lot.

After trying a string of donors who were tall and blond, I hit pay dirt on my first try with a short, redheaded Jewish donor with sky-high SAT scores. I didn’t actually choose him; staff at the clinic were convinced that I should give him a try. They were right.

Hannah Lily Abrams was born at 3:38 am on Tuesday, December 1, 1992. Tuesday’s child is full of grace, and Hannah means “grace.”

She was still in the nursery when I was wheeled into a private room at the hospital. I watched the minutes tick by on the clock. Finally, after 45 minutes, I called down to the nursery. “This is Tamar Abrams,” I said. “I would like to have my . . .” and I choked on the word “daughter.” I had imagined saying it for so many years that when the time arrived, I was unable to get it out. I finally managed to croak, “I would like to have my Hannah, please.”

My parents and several friends were at the hospital that night, and it didn’t occur to me that giving birth as a single mom required any special accommodation until the nurse brought me the birth-certificate form. All these years later, the line for “father” is still filled with asterisks, as though Hannah were the product of a woman and the stars. Perhaps a nod to Peter Pan?

• • •

Three weeks later, on the day after Christmas, I awoke to an icy wonderland outside our Arlington home and . . . silence. Hannah hadn’t nursed since 3 am, more than five hours earlier. I ran to her crib and found her looking pale and drowsy. Her skin was scaly, and she seemed uninterested in nursing. I called the pediatrician and asked if there was a special moisturizer for newborn skin. That set off alarm bells, and the nurse insisted we immediately go to the pediatrics office attached to Arlington Hospital (now Virginia Hospital Center).

When we arrived, we were whisked into an exam room. A nurse grabbed Hannah and race-walked her out of the office toward the hospital. It turned out she had mastitis—a breast infection that’s rare in newborns—and was very ill. By the time I gathered up the diaper bag and car seat, stopped at a pay phone to call my sister and parents, and made it to the neonatal ward, Hannah had IVs going into her skull and foot.

As a nursing mom, I was admitted, too. That week is a blur of doctor visits and the pain of seeing my baby hooked up to machines. My sister and friends were there a lot. A rabbi visited us once but provided little comfort. He asked where the baby’s father was, and someone ushered him out of the room.

I think it was the morning Hannah was taken away for a spinal tap that the precariousness of her situation began to sink in. But I had faith that she and I were meant to have a life together. After surgery and doses of antibiotics, she was well enough to go home on New Year’s Eve. It was her second hospital homecoming but the more significant one for me.

For a long time afterward, we settled into the bliss that infused my first Washingtonian story, but other challenges were ahead.

At 20 months, Hannah was able to walk down the six steps from our house to the driveway, but she preferred to be carried. One August morning, as I held her on my hip and descended the steps, a car door slammed and Hannah twisted violently. In an instant, she was out of my grasp, plunging headfirst toward the bottom of the stairs. I learned in that moment that I would do anything to save my child. I launched myself from the top step, catching her in midair and twisting so I wouldn’t land on my head. We both ended up on the ground, Hannah unscathed and my legs in agony.

A neighbor came running, and within minutes I was in an ambulance. I recall so clearly the doctor on duty telling me I had broken both my ankles, and my response: “I can’t have two broken legs. I’m a single mother of a toddler.”

The next months were the hardest of my life. My brother hired a woman who came for a few hours every day to help with chores while my family, friends, and neighbors all pitched in. Members of our baby group came every weekend to spirit Hannah off on adventures, and the two of us read many books together. My orthopedist was astonished when he was able to remove one cast after only six weeks, underestimating my determination to regain a leg to stand on.

At some point, the story became hers.

Around the time of Hannah’s Peter Pan declaration, I would ask questions such as “What would you do with a dad if you had one?” She wasn’t sure. Her life was filled with family and friends and school and a mom who worked part-time from home, to be available for bake sales, PTA meetings, school plays, and parties.

When Hannah turned seven, she started asking tougher questions. I decided to show her the 20-page questionnaire her donor had filled out. She read it word for word: his family’s medical history going back several generations, his favorite music and sports, his near-perfect SAT scores. And then she wept. We both did. When she could speak, she said, “I think he would like me.”

I knew that in addition to not having a dad, as an only child Hannah would miss out on the sibling experience. That was part of my motivation for becoming a foster parent. Our first foster child was the only baby abandoned in Arlington County in 27 years. Mary Agnes—named by the priest at the church where she was left as a newborn—became Molly under our roof. I collected her from Arlington Hospital on her third day of life and brought her home to my kindergartner, who was initially ambivalent about this noisy, demanding baby. When Molly was returned to her mother several months later, Hannah and I were both devastated. We had learned there was room in our family for one more.

Over the next 12 years, a procession of about 20 babies and children joined us, some for longer than others. Hannah experienced jealously, frustration, and deep love. One of our favorites was roly-poly Will, who came to us when he was five months and left for an adoptive family around his first birthday. Hannah taught him to clap his hands, play peekaboo, and eat Cheerios. She also yelled at me on several occasions: “You love Will more than you love me!”

One of our foster children was so clingy that she frequently caused Hannah to retreat behind locked doors.

“Why does she want everyone to love her?” eight-year-old Hannah asked.

I said: “Because no one ever has.”

• • •

Around that time, I fell in love. I had been reluctant to bring men into Hannah’s life, but then I met Cliff. He was tall and bearded, a Westerner. So incongruous in Washington with his bolo ties and sun-weathered skin. Divorced and childless, he gathered Hannah and me to him with both arms.

Cliff taught my daughter to play pool and took her whitewater rafting. In New Mexico for Christmas one year, I realized I hadn’t seen Hannah for a while. When I asked Cliff’s sister-in-law, she pointed to the roof. Cliff, his brothers, and Hannah were atop the flat-roofed house lighting candles inside paper bags to serve as luminarias. She grinned wickedly at me, knowing I would never have given her permission to stand on a roof.

We took trips to Grand Teton and Yellowstone, to Amish country and across the East Coast. We talked about marriage, and I began to understand what it was like to not always be in charge. At Hannah’s bat mitzvah, Cliff helped hoist the chair on which she sat and participated in what must have been a totally foreign ritual to him.

And then, five years after he entered our lives, he was gone. Left the country on a government assignment and never came back.

Now we knew what we were missing.

Hannah handled it as well as a middle-schooler handles anything. She chose to write an essay for English class about being the child of a single mother, flouting her differentness when she didn’t have to. As she made her way into high school, several of her friends’ parents divorced. We became close with neighbors—Nelson, a divorced dad, and his daughter, Hillary, four years younger than Hannah—and began taking vacations to Rehoboth with them. As I looked around, fewer families resembled the Cleavers.

I’ve never regretted the decision to have Hannah, but there have been many times when I’ve felt bad that I gave her a life without a dad. I’ve always disliked the term “single mother by choice.” I am a single mother by default. Yet I’m proud that Hannah is okay and that her future is less determined by her lack of a father than by the values and character she has developed with my guidance.

Hannah is heading into her third year at Drexel University in Philadelphia, but our house is still decorated with multicolored Post-it notes Hannah and I wrote to each other over the years. One near my bedroom light switch, written in her curlicue scrawl, reads, “Believe in yourself, because I do.” Another she wrote hangs in the kitchen: “I love you so much. Even in 30 or so years, I will still be bragging to all of my friends about how cool my mom is. . . .” My notes to her describe my pride in her accomplishments or, for a series written before I headed to Africa for a few weeks when she was 18, tell her how much I love her and will miss her.

I may never take them down.

• • •

My grandmother, at age 97, told me: “Honey, you are so lucky that you have the choices you do. I envy that.”

But the choices I had in 1992 are archaic compared with those women have today. When I was trying to conceive, I would leaf through a binder filled with handwritten donor forms, using a copy machine when I found a promising one. Today the sperm bank I used—California Cryobank—has “donor-matching consultants” who will compare potential donors’ photos to pictures of your spouse or relatives. Fairfax Cryobank has a Fairfax FaceMatch technology in which you can electronically match characteristics of photos you have to potential donors.

But there are looming problems for the offspring of anonymous donors. My friend Rebecca Blackwell, who lives in Frederick, became pregnant with her son, Tyler, through an anonymous donor shortly after I conceived. She managed to track down her donor a few years ago and discovered he had a genetic and potentially fatal heart defect. He had fathered dozens of children and wasn’t required by law to inform the sperm banks of his heart problem, which Tyler inherited.

Tyler had to have surgery, and Rebecca has made it her mission to find and inform the donor’s other offspring. She’s also pushing legislators to follow Washington state’s lead in granting donor-conceived people the right to crucial health information about their biological parents.

Just after her 18th birthday, Hannah learned firsthand that anonymity is a bitter pill. We had discussed for years that when she turned 18 she could send a letter to her donor in care of the sperm bank. As the date approached, she spent time crafting her letter. She attached photos of herself at different ages. She didn’t let me read the letter, but she told me she had assured him she didn’t want a relationship. She merely wanted him to know a little about who she was.

Hannah was in the hallway of her high school, between classes, when a woman from the sperm bank called her to say the donor didn’t want the letter forwarded to him. The woman expressed surprise because he had recently updated his contact information.

Hannah couldn’t stop crying when she arrived home after school. She didn’t understand why he wouldn’t want the letter, at least out of curiosity. We knew Hannah was the eldest of any offspring, so her letter would have been the first one for that donor. I couldn’t find the right words to explain why a middle-aged man might want to forget about what had simply been an easy way to earn money as a college student.

Hannah doesn’t talk about her donor anymore, at least not to me. But if a single woman contemplating anonymous-donor insemination asked me for advice today, I’d tell her about the moment when Hannah heard that her donor didn’t want to know who she was. It balances the equation of those early days of bliss.

Looking back at my first Washingtonian article, I’m struck by how happy I was as a mother. That hasn’t changed. But single motherhood no longer defines either my life or my daughter’s, and hasn’t for a while.

After Hannah’s bat mitzvah at Temple Rodef Shalom in Falls Church, we headed to a nearby hotel ballroom for the celebration. As it began, we called guests to come forward in groups to light a candle as I explained their significance to us. My family, Hannah’s softball teammates, friends old and new, and others came to stand at the center of the room with us. There was even a candle, which I lit, for all of our relatives and friends who had touched our lives before they died.

When the last candle was lit, 125 of our dearest friends and family surrounded Hannah and me. Before we disbanded to dance and eat brisket, I looked around and knew my daughter was being raised by more than a single mother.

On the door of our Arlington house is a plaque that I picked up somewhere in our travels. It always makes me smile: And so they lived happily ever after.

Tamar Abrams is a writer and communications consultant with a special interest in global health and development, foster care, and adoption and gender issues. She can be reached at tamarabrams@verizon.net or on twitter @tamarabrams.

This article appears in the August 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.