Only her friends and neighbors, knowledgeable art lovers, and congregants of the synagogue across the street knew about the wondrous secret in Evelyn Nef’s Georgetown garden. One of Washington’s truly hidden treasures, it shimmered in the sunlight with turquoises, corals, and golds and brought cars to a screeching halt when drivers coming down 28th Street caught a glimpse over the garden wall. For more than 35 years, the masterpiece was Nef’s pride and joy.

A gorgeous mosaic of Murano glass and natural colored Italian stone, the work of art had been a gift to Nef and her husband, John, an economic historian, from a very close friend: Marc Chagall.

One of the most famous artists of the 20th century, Chagall, along with his wife, Valentine, or “Vava,” spent summers with the Nefs in the south of France. When Chagall visited the couple at their Georgetown home in 1968, he told them he wanted to do something for the residence, later amending his plan: “No, the house is perfect. I’ll make a mosaic for the garden.”

Evelyn pictured a small plaque she could hang on the garden wall. But Chagall—who created works in nearly every medium, designing stage sets and soaring stained-glass windows as well as painting the ceiling of the Paris Opera—had something else in mind, something as colorful and grand as his longtime Washington friends.

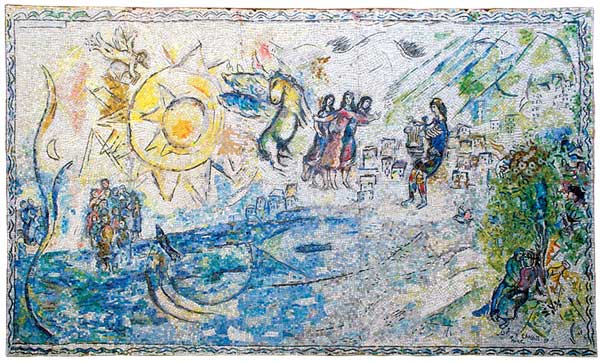

The untitled mosaic that was unveiled in the back yard near 28th and N streets in 1971, with Chagall’s signature in the lower right corner and the 84-year-old artist himself in attendance, was spectacular—a 10-by-17-foot work that was unlike anything he’d ever done but incorporated many of his favorite themes. “Everything you want in a Chagall,” says Harry Cooper, curator of modern and contemporary art at the National Gallery of Art.

The Nefs cherished the mosaic, seeing it as an expression of Chagall’s fondness for them. Not a day passed by that Evelyn didn’t take notice of the lustrous work of art in her garden and how the stones changed hue with the weather and time of day. When John Nef died in 1988, she buried his ashes at the base of the cherished masterpiece, in the shadow of their tall magnolia tree.

But she also loved sharing her treasure. The child of Hungarian Jewish immigrants, Evelyn would leave her garden door open on the Jewish High Holy Days so those leaving services at Kesher Israel synagogue across the street could stop in for a contemplative moment in a beautiful setting. She threw garden parties in May when the flowers were in bloom.

All along, she planned for her beloved mosaic to live on beyond her years in a place where it could be shared by millions.

When Evelyn Nef died at age 96 in December 2009, she left the Chagall mosaic to the National Gallery of Art, along with a trove of works that she and her husband had collected over the years and that lined the walls of their home: dozens of drawings and prints by artists such as Picasso, Whistler, Renoir, Vuillard, Kandinsky, and of course their friend Chagall.

The museum spent five weeks last spring taking the mosaic down—a project that required conservators, curators, art handlers, designers, carpenters, masons, a security force, registrars, mosaic experts, lawyers, and administrators—and now will spend the next one to two years cleaning and restoring it and, sometime in 2012, installing it in the National Gallery’s sculpture garden, as Nef desired.

“It’s a very unique and important work of art that we’re delighted to have and honored to have,” says National Gallery director Earl A. “Rusty” Powell. “It’s a tribute to her wonderful life and great memory. It meant so much to her.”

Powell says Nef talked about her desire for the mosaic to go to the National Gallery from the day he met the enthusiastic arts patron in 1992, his first year as director. Nef became even more excited about the idea after the museum’s sculpture garden went up in 1999. “There wasn’t a negotiation,” says Powell, who became a good friend of Nef’s. “She didn’t want anything in return. She was very generous of spirit.”

Evelyn Stefansson Nef, born Evelyn Schwartz, had been at various times a puppeteer, an expert on Arctic exploration, an author, a psychotherapist, and an arts benefactor who supported not only the National Gallery but also the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the National Symphony Orchestra, and the Washington Opera.

The high-spirited life she led in Washington with her third husband, John Nef—a life in which fresh flowers, art, music, and legendary 1930s-style parties filled the house—was a far cry from her joyless childhood in Brooklyn as the daughter of a severely depressed mother who went mute after her husband died when Evelyn was 13.

In 1932, just out of high school, Evelyn married puppeteer Bil Baird—after an intense affair with “Bucky,” famed architect Buckminster Fuller, who was twice her age and married—and she learned to make marionettes, perform, and sing.

But she and Baird divorced after four years, and in 1941 she married Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson. Evelyn was entranced and inspired by her new husband’s intellect and made his passion hers—becoming his research assistant, reading everything he’d written, and accompanying him on expeditions.

“Listening to him conversing with a fellow scientist or writer was like listening to a Bach two-part invention,” she wrote in her 2002 autobiography, Finding My Way: The Autobiography of an Optimist. “Stef introduced me to new words, new names, new books, unimagined joys of poetry, an explosion of new possibilities.”

She became such an expert on polar exploration that she wrote three books on the subject, lectured at Dartmouth College, where her husband began a polar-studies program, and later became president of the Society of Woman Geographers.

Stefansson, who was 34 years older than Evelyn, died in 1962. A year later, two months before John F. Kennedy was assassinated, Evelyn moved to Washington to take a job at the American Sociological Association, which had headquarters in the annex of the Brookings Institution.

At a party in New York in January 1964, she met John Ulric Nef, a 63-year-old widower who was a renowned economic historian and professor with a home in DC’s Kalorama and a love of all things French. Five days later, at lunch in a private dining room at Brookings, Evelyn accepted John’s proposal of marriage.

John Nef had founded the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago and brought to the school a galaxy of authors, artists, and thinkers to speak—everyone from T.S. Eliot to Igor Stravinsky to Frank Lloyd Wright and Marc Chagall. Chagall stayed at John Nef’s place when he came to the university and saw, among the many works of art on the professor’s walls, two of his own paintings. It was the start of a beautiful friendship.

Evelyn and John sent a wedding announcement to Chagall, who embellished it with a sketch of a woman holding a bouquet of flowers and sent it back to the newlyweds. The Chagall-adorned announcement hung in the Nefs’ bedroom, beneath a Chagall gouache of a Purim festival, and is among many such personal drawings in the collection Nef left to the National Gallery.

The Nefs and Chagalls began vacationing together at Cap d’Antibes, a resort in the south of France, where each year they celebrated Evelyn and Marc’s July birthdays with a bash at the Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc. Chagall liked to draw a little sketch or watercolor on the printed menu card—always the same menu: caviar and rack of lamb—with the seal from the hotel as a woman’s hat. The menu cards, with personal dedications, are also part of the National Gallery bequest.

Chagall designed the sprawling mosaic for the Nefs at his studio in France and hired Italian mosaic artist Lino Melano—who created mosaics for Picasso, Fernand Léger, and Georges Braque—to translate his brilliant gouache painting to rough-cut stone and glass and then come to the United States to install it.

The main figures in the mosaic are from Greek mythology: Orpheus and his lute, the Three Graces, and the winged horse, Pegasus, all to the right of three golden concentric suns. In the left corner is a scene of immigrants crossing a wide blue ocean to come to America, a nod to Chagall’s own history: During World War II, the Jewish artist had been smuggled out of Nazi-occupied France by the International Rescue Committee and found refuge in New York. In the lower right corner of the mosaic are two lovers sitting under a tree. “John and me?” Evelyn asked Chagall. He replied: “If you like.”

The work of art “doesn’t have any reason to hang together,” says Harry Cooper of the National Gallery, “but I think it does.”

Shipping the mosaic to the United States and installing it wasn’t easy. The Nefs had to erect a 30-foot wall to hold the artwork. Chagall wanted a smooth, light-colored wall, but the DC Fine Arts Commission insisted it be brick to fit in with Georgetown architecture. So a brick wall went up. Chagall declared it a cauchemar—a nightmare—then asked for a brush and began to mix paint until he found a suitable shade of gray to cover the brick.

The mosaic was shipped to Dulles Airport in ten panels, each backed with its own iron grid laid into the concrete and then covered with newspaper. Once in the wall, the panels were secured together with iron clasps. Then Melano, the mosaic artist, placed the final stones in mortar at all the seams where the panels came together as well as around the periphery.

“On November 1, 1971,” Evelyn wrote of the unveiling, “Marc and Vava arrived, the French Ambassador Charles Lucet made a speech, John made an exquisite, short speech in French, and then we all traipsed out to the garden in the fading late-afternoon light. The artificial lights were turned on and the dazzling display appeared to a hushed silence followed by a roar of applause. . . . It seems like a living presence and, of course, it says, ‘Marc loved us.’ ”

When curator Andrew Robison came to the National Gallery in the mid-1970s, he wanted to find out who in town collected prints, drawings, and watercolors and was interested in the museum. The Nefs were among those at the top of the list, and he sought them out. Robison, senior curator of prints and drawings, eventually became friends with Evelyn as well as a regular at her parties—the New Year’s Eve affairs at her house in Georgetown where dinner wasn’t served until after midnight, the birthday parties for Evelyn at her contemporary home in the Berkshires where cellist Yo-Yo Ma once played.

Evelyn’s soirees reminded Rusty Powell of what the 19th-century salons must have been like in Europe. “She would always have people of different walks of life,” the museum director says, “and she’d stir this social soup in a way that was very interesting and great fun.”

Nef in her later years was no less of a force. At 60, armed with only a high-school diploma, she trained to be a psychotherapist. On her 80th birthday, intent on achieving a flat stomach, she hired a personal trainer and started pumping iron; eventually she was doing more than 300 sit-ups.

Robison says he admired Evelyn’s combination of femininity, intellect, and joie de vivre: “She had this fantastic feminist life where she went through three husbands and one great lover, adapted herself to each of them, always reinvented herself, and then reinvented herself for the fifth time after her last husband died.”

Following John’s death, Evelyn gave up her psychotherapy practice and taught herself everything she needed to know about finance and philanthropy. “My first move was to subscribe to the Wall Street Journal, which I read religiously, at first without much understanding,” she wrote. “But in time I accumulated enough knowledge to feel capable of making informed and sensible decisions.”

John had wanted his art collection to go to the National Gallery, and Evelyn liked the idea. She had nieces and nephews, though no children, but “she really thought that the art belonged in a museum,” says Robison.

Aside from supporting the local symphony and opera, Evelyn gave money every year to the National Gallery and the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Robison invited her to get more involved, suggesting she put her money toward a specific work that the museum wanted to purchase instead of blindly writing a check.

So every December, Evelyn made a donation. Then Robison would invite her to lunch and to the print room, where he would show her two or three works the museum could buy with her money, ask her to help choose, and give her a mini-seminar. The routine pleased them both: “She’d say, ‘When are we going to have another session?’ And I’d say, ‘Well, you have to give some money,’ ” Robison says with a smile.

For the museum’s 50th anniversary in 1991, Robison had his eye on two pieces in Nef’s collection. “I screwed up my courage, and I asked her to think about giving her two most important works: a Picasso gouache and an early Chagall gouache.” She was amenable, Robison says, but didn’t want to live without the cherished works on her walls, especially the Chagall.

The curator made a facsimile of it for Evelyn, putting the work in the same frame with the same mat so she could hang it in her home while the original went to the museum.

She was thrilled. And Robison eventually started making facsimiles for her of works the museum bought with her money. The likenesses, eventually made through digital photography, were good—so good, says Robison, that the auction house that assessed her collection after she died assigned very high values to some of the copies. “It didn’t recognize that they were facsimiles,” he says.

The National Gallery’s curators and conservators had to develop several scenarios for taking the mosaic down from Nef’s garden. “We had very little to go on because we didn’t know how it had been installed,” says senior conservator Shelley Sturman.

Had it been completely cemented into the wall, dismantling it would have been trickier—and riskier to the artwork—than it was.

After building two-level scaffolding with a roof and removing bricks from all around the perimeter of the mosaic, the workers discovered the best of all possible outcomes: An air space had been left between the mosaic and the wall.

The museum crew installed steel beams to support the wall and then decided to take the mosaic down much as it had been put up: working one panel at a time and removing all the tesserae—the pieces of stone and glass—around the border of each panel so the rusted and corroded iron clamps holding the ten segments together could be removed.

They took scale photos of all the borders and seams and then removed the tesserae from these areas one by one, repositioning the stones with flour paste on the photos so they’d know exactly where each stone went when they were ready to assemble the mosaic again.

Then, one by one, each of the ten panels was removed, covered with three layers of a protective cotton cloth on the front surface, placed in foam-insulated crates, and shipped to the museum’s off-site production facility.

There, the backs of the mosaic panels are being worked on—all of the iron is being removed and replaced with stainless-steel grids.

After each panel is refitted with new metalwork, it will be shipped to the object-conservation lab at the museum, where the cotton layers will be removed and the front side of the mosaic cleaned. Soon the National Gallery staff will be faced with the question of how to install the Chagall in its sculpture garden. “We might decide that we want to rebuild it exactly the way they did in 1970,” says conservator Sturman. “It worked beautifully then. It stood the test of time.”

Meanwhile, the tall brick wall on N Street has been restored, and John’s ashes, once buried at its base, have been moved to Hanover, New Hampshire, where they’re interred alongside Evelyn and her second husband, Vilhjalmur Stefansson. Soon after Evelyn’s death, curator Andrew Robison spent a couple of days at her Georgetown home going through every book that lined the living-room shelves. He found dozens that had been personally dedicated, including many with a whimsical crayon drawing on the title page and words of obvious affection: “Pour les amis Nef, Marc Chagall.”

This article first appeared in the January 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.