Illustration by Bryan Christie

Sometime this century, a storm will form in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Africa. It will gather strength as it drifts west, gradually acquiring the round swirl of a hurricane. As it approaches the Caribbean islands, it will turn northwest toward the East Coast of the United States. When it enters the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, its winds will exceed 100 miles an hour.

Hurricanes of this magnitude have hit the Washington area before. But this storm will be different. The level of the Atlantic Ocean, Chesapeake Bay, and tidal Potomac River will have risen one to three feet—and possibly more—because of melting glaciers and a warming climate. Hurricanes will ride toward land on these swollen seas like surfers on a massive swell.

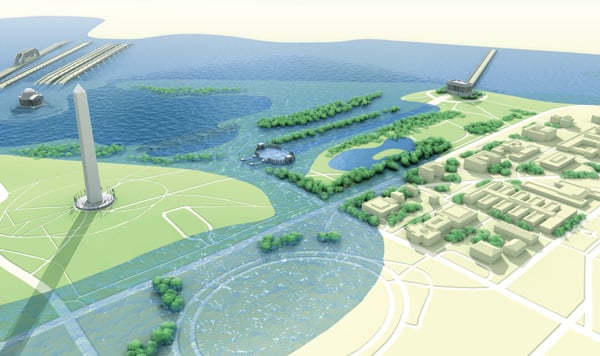

When that hurricane hits Washington, here’s what we can expect: The Potomac will quickly rise to flood the low parts of Alexandria, Georgetown, and Southeast DC. Soon the river will cover Hains Point, East Potomac Park, and the land separating the Tidal Basin from the river. The Tidal Basin will overflow, flooding the World War II Memorial and the Reflecting Pool.

This is where the situation gets interesting. Unless flood-control devices have been erected, the rising water will flow north along 17th Street, pooling at the edge of the Ellipse. Then it will pour down Constitution Avenue into the Federal Triangle area, flooding most of the buildings bounded by Pennsylvania Avenue, Constitution Avenue, and 15th Street.

“There’s a sort of bowl there that’s pretty much the lowest point in the city,” says Michelle Desiderio, a planner with the National Capital Planning Commission. “North of Pennsylvania Avenue, the land starts to rise again.”

Washington has ways to protect itself from such a storm. But the threat from high water is increasing. The Potomac’s level has risen about a foot in the past 100 years, so hurricanes already cause more damage than they used to. And the river is now rising about an inch a decade, with greater increases possible as global warming intensifies.

Also, glaciologists are worried about two major icecaps—on Greenland and the western part of Antarctica. If the ice on Greenland melts, sea level would rise at least 20 feet. If western Antarctica also melts, sea level would rise another 15 feet or more. In Washington, 20 feet of sea-level rise would cover large parts of the Mall, Reagan National Airport, and the Washington Navy Yard. Thirty-five feet would bring the Atlantic Ocean to within a stone’s throw of the White House.

No one knows the likelihood of really big sea-level increases. The flow of glaciers across the rocky surfaces of Greenland and Antarctica is too complicated to model with computers. And it makes a big difference if sea level rises 20 feet over a hundred years or a thousand.

But it’s not too early to start thinking about how cities such as Washington will deal with higher water levels. A sea-level rise of one to three feet over the next century is virtually guaranteed. And if the ice on Greenland or western Antarctica starts to give way, all bets are off.

Many places will suffer more than Washington as sea level rises. Still, using Washington as an example forces us to ask what kinds of risks we are willing to take.

It’s a late-summer day, and the Potomac River is thick and motionless in the afternoon heat. On one side of our boat, a doe picks her way along the narrow shoreline of Roosevelt Island. On the other side, rowers prepare to launch their shells from the Georgetown boathouse.

Jim Titus, manager of the Environmental Protection Agency’s sea-level-rise program, gestures toward the doe. “This side of the river will probably look about the same as sea level rises,” he says, “because a decision has been made to keep this shoreline natural.” He turns to face Georgetown: “This side of the river, I don’t know.”

Titus has been thinking about sea-level rise for most of his adult life. He graduated from the University of Maryland in 1978 eager to protect the environment and went to work for EPA the following year. Global warming was just entering the national consciousness, and “EPA wasn’t looking for someone to help stop the greenhouse effect,” Titus says. “But there was this guy, John Hoffman, a really brilliant guy, and he made the connection that this was a serious problem. He remembered that I would always come up and talk to him about the greenhouse effect, so he eventually decided to hire me, and that was my charge—to understand the consequences of sea-level rise.”

Titus focused part of his early efforts on the more dramatic projections of sea-level rise. A paper published in the journal Nature in 1978 had speculated about the breakup of the western-Antarctica ice sheet. Titus and his EPA colleagues included similarly dramatic scenarios in a 1983 report on climate change, which called on the government to take steps to combat global warming.

The political fallout was fierce. George Keyworth, science adviser to President Reagan, called the EPA report “unwarranted and unnecessarily alarmist.” Keyworth instead endorsed a new National Academy of Sciences report on climate change. The irony, Titus says, is that the NAS report said pretty much the same thing.

Titus wasn’t discouraged by the political pushback. He learned everything he could about coastal processes and hydrology, got a law degree from Georgetown, established a network of connections with scientists inside and outside the government, and continued studying the issue.

He found plenty to do without worrying about dramatic scenarios. “As a society,” he says, “we haven’t made the adaptations that are justified by the current rate of sea-level rise.”

From the middle of the Potomac River, the damage caused by past sea-level rise is easy to see. Much of the Mall is perched on stone seawalls built since the end of the 19th century by the US Army Corps of Engineers. In many places, the seawalls are crumbling from age and high water. Behind the seawalls, parts of the Mall have slumped so badly that they’re underwater during high tides.

Twenty years ago, I used to run around East Potomac Park on the sidewalk adjoining the seawall. Today the sidewalk is so tilted that it would ruin my knees within a mile or two.

Titus and I are heading down the Potomac in a 19-foot outboard named Nothing But the Truth. Our pilot, George Stevens, who runs the Belle Haven Marina just south of Old Town, knows all about the power of water. When Hurricane Isabel roared up the Potomac in September 2003, his marina was covered by nine feet of water.

“We were devastated,” he says. “Our docks looked like the Coney Island roller coaster.”

Stevens had moved all of the marina’s boats and trucks to a parking lot a third of a mile inland. Still, boats floated off their trailers and ended up strewn across the parking lot.

Stevens steers Nothing But the Truth around Hains Point, and we head up the Anacostia River. In the distance, cranes rise above the new baseball stadium. The brick façade of the National War College looks out at the point of land where the Potomac and Anacostia rivers meet. As we proceed up the Anacostia, the shoreline looks increasingly industrial and ignored.

“The only good way to see the Anacostia is from the water,” Titus says.

When Titus was born in 1955, his parents lived on a 75-foot Coast Guard cutter moored at the Buzzard Point Marina, just south of the new Nationals stadium.

“My parents thought I was a colicky baby because after I was born we lived in an apartment for two weeks,” he says. “But as soon as we moved back onto the boat, I quieted down. That was before doctors knew how much babies hear and feel when they’re in the womb.”

Although his family moved to a house along Swan Creek when he was two, Titus spent most weekends on the Southeast DC waterfront until he was eight. After the cutter sank in a storm, his father raised it and moved it to Swan Creek.

“I thought the National War College was a church because it had a stained-glass window,” Titus says. Pointing to the smokestacks of the Buzzard Point power plant, he continues: “I figure that my whole future was preordained by living on a boat beneath a power plant when I was a baby.”

If there’s one phrase that comes to mind when viewing Washington’s shoreline, it’s “lost opportunities.” Washington has 45 miles of riverfront along the Potomac, the Anacostia, and their channels. Large sections of that are inaccessible, and many accessible portions have little to offer. There’s no place in Southeast or Southwest DC to board a scheduled water taxi to see Washington as George Washington might have seen it on trips up the Potomac from Mount Vernon. As a final indignity, Stevens has to turn Nothing But the Truth around just past the Pennsylvania Avenue Bridge, where the tracks of the CSX railroad block anything larger than a kayak from continuing up the Anacostia.

Several years ago, in a report on Washington’s waterfronts, the National Capital Planning Commission painted a grand picture of river walks, mixed-use development, and lush parkland in Southeast and Southwest DC. Most of those plans are still on the drawing boards, but there is some progress, especially around the new baseball stadium.

This fall, a two-mile section of the Anacostia Riverwalk opens in October—part of a planned 22-mile multiuse trail along the western and eastern banks of the river. New parks are being built to connect the stadium to the Anacostia.

Obstacles remain to the development of Washington’s waterfront. Many governmental and private organizations own parts of it, and getting them to work together is hard. The river and riverbanks are often dirty from inadequate water-treatment facilities upstream.

Amid all the other problems of getting Southeast and Southwest DC rebuilt, sea-level rise ranks fairly low. That’s probably appropriate, Titus says, as long as developers remember that the river won’t always be placid.

Where seawalls are rebuilt, they’ll need to be tall enough to withstand high water. To protect against storms, floodgates like those built into Georgetown’s Washington Harbour may be necessary.

A better option, says Titus, would be to rely on “living shorelines” that combine plants, stone, sand, and other materials to control a riverbank. Sea level will gradually inch up either a rebuilt seawall or a living shoreline. But as long as planners and developers take rising sea levels into account, Washington’s shorelines can be protected. “I’m just trying to get people to think about sea-level rise and prepare for it,” Titus says.

Tidal marshes are the early-warning systems of sea-level rise. Sitting between open water and dry land, they’re sensitive to both the level of the water and what the water contains. “In a marsh, everything is connected,” Inga Clark says. “One thing leads to another thing leads to another thing.”

Clark and I are walking through a green corridor of vegetation at Dyke Marsh, just south of Alexandria. As we round a bend and emerge from the trees, the Wilson Bridge swings into view, as do jets flying toward Reagan National Airport. Yet the loudest sounds remain the red-winged blackbirds calling for mates among the cattails.

Clark, who studied geology and hydrology at George Washington University before going to work at the US Geological Survey, is a number cruncher. She combines geographic data from tide gauges and satellite measurements to predict how sea-level rise might affect landforms. A few years ago, she and her boss, Curt Larsen, who recently retired from the Geological Survey, along with several colleagues studied the Eastern Shore’s Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, a 27,000-acre reserve of tidal marshland south of Cambridge, Maryland. Their study was one of the most dramatic done to date on the effects of sea-level rise.

Since 1938, pilots have been flying over Blackwater and taking pictures of the marsh. The older photos show a marsh rich with vegetation, with relatively little open water. Over the years, the areas of open water have expanded. Today the refuge is losing 130 acres of marsh a year to the encroaching sea.

Clark, Larsen, and their coworkers calculated how long the marsh would last given the current rate of sea-level rise. By 2050, they say, most of Blackwater will be open water. As sea level rises, the water gets more salty. The saltwater stresses freshwater plants, and the saltwater plants that become more common can’t supply enough biomass to save the marsh. “It’s a chain reaction,” Clark says.

I invited her to meet me at Dyke Marsh so I could ask an expert what will happen to it. Immediately, she began to notice differences between Dyke Marsh and Blackwater. Dyke Marsh is farther from the Atlantic, so its water is fresher. Parts of the marsh are higher than Blackwater, much of which is a foot or less above sea level. Most important, Dyke Marsh has a much richer source of sediment—the eroding farmlands and riverbanks of the Potomac and Anacostia that give the rivers their thick, brown consistency.

As long as sea-level rise is moderate, marshes can survive by accumulating sediments and moving inland. That’s probably what will happen at Dyke Marsh as the Potomac rises, Clark says. The marsh will become higher and will invade what today is dry land.

But eventually it will run up against the George Washington Memorial Parkway. It will have nowhere else to go.

The same thing is happening elsewhere around the world. As sea level rises, the shoreline moves inland. Many owners of waterfront property build seawalls at the edge of dry land. At first the seawalls are needed just for high tides and storms. But as the sea continues to rise, the beaches, tideflats, and marshes between the sea and seawall drown. Eventually, there is only open water on the other side of the seawall.

The property owner may not lose land, but the public does. In most states, the land between low tide and high tide is public land. Seawalls essentially guarantee that the public will be giving up its right to use the shoreline.

Titus has an idea about how to preserve the public trust. He advocates what he calls rolling easements. Waterfront-property owners could continue to build on their land. But they couldn’t build any structures that hold back the sea. As sea level rises and consumes their property, they and not the public would have to give up land. The biggest problem is political: Rolling easements look a lot like governmental appropriation of private property.

Much more than property rights is at stake. A shoreline that consists of dry land, seawalls, and open water is biologically impoverished. Marshes provide breeding grounds for fish, crabs, birds, and many other organisms. Without marshes, the wildlife of the Chesapeake Bay and other estuaries will be decimated. And according to the Norfolk-based organization Wetlands Watch, 50 to 80 percent of the tidal marshes that surround the Chesapeake today will disappear over the next century because of sea-level rise unless dry lands adjacent to the marshes are set aside to become future marshland. The result of such a loss, says Wetlands Watch executive director Skip Stiles, would be “an ecosystem collapse.”

The peacefulness of a marsh can be deceptive. This is where some of the first battles over rising sea levels will be fought.

A few days after Hurricane Isabel hit in 2003, University of Maryland coastal scientist Michael Kearney drove around the Chesapeake Bay to look at the damage. Many areas near the shoreline were a mess. Houses were full of debris, power lines down, roads washed away.

But even as he was looking at the destruction, Kearney was thinking about something else. “Isabel wasn’t even a hurricane when it entered the bay,” he says. “It was a tropical storm at best. It’s just a question of time before we have a much bigger storm.”

No one can predict when that storm will arrive. “It could be a century from now or it could be next year,” Kearney says. What we do know is that the damage will be horrendous. Isabel caused 44 deaths and more than $1.3 billion in damage in Virginia, Maryland, and the District. A Category 3 hurricane coming directly up the bay could be dramatically more destructive, Kearney says.

If sea-level rise is the message, hurricanes are the messenger. A rising water level moves the shoreline landward, so waves from a storm break farther inland. Deeper water also makes for larger waves, which do “much of the damage in a storm,” Kearney says. And the warmer temperatures responsible for higher sea levels may be contributing to stronger hurricanes, though scientists are arguing about that. All of these factors will make the potential for hurricane damage “a lot worse than it is now,” Kearney says. “And we’re going to see it a lot sooner than people think.”

Actually, we’ve already seen it. Sea-level rise was a direct contributor to the Hurricane Katrina disaster. Higher water levels have been destroying the Louisiana coast’s marshlands, which historically have absorbed some of the force of hurricanes. And high seas made it that much easier for the storm to breach New Orleans’s levies and flood the city. The result was the nation’s costliest natural disaster, with more than 1,800 deaths and $100 billion in damage.

People in the rest of the country might shake their heads at the folly of building houses below sea level, as was done in New Orleans. But when Kearney looks at the Eastern Shore, he doesn’t see much difference.

“There’s been considerable development in areas that in my opinion shouldn’t be considered for development,” he says. On Kent Island, on the other side of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge from Annapolis, “I can’t believe that those new homes wouldn’t be at severe risk from a major hurricane.”

Rising sea levels already have done serious damage to property abutting the bay. When sea level goes up, the water doesn’t simply creep up the existing shoreline. The land adjusts to the changing sea, sometimes dramatically. Sharps Island, mapped by John Smith in 1608, no longer exists; a lighthouse built on the island in 1882 sits in seven feet of water. Smith Island has lost 30 percent of its land mass to the sea and will disappear in this century unless built up with fill.

Even Eastern Shore houses that seem safely inland are at risk because of flat ground and treacherous shoreline dynamics. In some places, “you have to go a couple of miles inland to get two feet above mean tide level,” Kearney says.

Maryland has been more progressive than most other coastal states in thinking about rising sea levels. In 2000, a young coastal planner named Zoë Johnson received a fellowship to prepare a sea-level-rise response strategy for the state. She found that people were eager to talk with her about the encroaching water.

“Maryland has known for a long time that it has a sea-level-rise problem because the impacts are so readily apparent,” says Johnson, who now works for the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. With the state losing 580 acres a year to shore erosion, “you don’t need to convince people that something is going on.”

Earlier this year, Maryland governor Martin O’Malley established a climate-change commission that will look at sea-level rise. Johnson is enthusiastic about the commission, but she warns, “It takes a lot of work to get the adaptation components built into the local level. The issues that I raised in my report are still issues that we need to overcome.”

Then again, government action may not be the most effective way to combat sea-level rise. What will stop shoreline development, according to Kearney, is in the private sector—the insurance industry.

“For most barrier islands on the East Coast, the insurance companies have quit writing policies,” he says, “and it’s only a matter of time before they quit covering other areas.” The result will be a dramatic drop in coastal property values and construction: “We’re one major storm away from stopping all this development.”

The federal government could step in. But Kearney doesn’t expect that to happen, especially given its reluctance to rescue New Orleans. “The federal government isn’t going to keep building your house for you every few years,” he says. “That means the property is pretty much worthless. I think the glory days are over.”

Most people don’t realize that Washington has an extensive area that would flood regularly if not for a levee system. But that’s because most people don’t go there.

The Anacostia Naval Air Station and Bolling Air Force Base, on the eastern shore of the Anacostia and Potomac rivers, sit largely on tide flats separated from the water by a 12-foot levee. From a small boat on the Potomac, the roofs of the base housing peek above the barrier’s crest. If the Anacostia Levee ever overtopped during a storm, both bases would quickly founder.

Washington has another levee system that most people have never noticed, though they may have walked on it many times. Just to the north of the Reflecting Pool, between the Lincoln Memorial and World War II Memorial, is an odd meandering hill. “You have to know it’s there and be looking for it to notice it,” says Anthony Vidal of the US Army Corps of Engineers’ Baltimore district, who’s in charge of levee safety in our region.

The corps built that mound of earth in the 1930s and ’40s following severe floods in 1924, 1936, 1937, and 1942. It was designed to protect everything from the State Department to Union Station. There’s just one problem: It has never been finished.

The Potomac Park Levee, as it’s known, has two main gaps. One is on 23rd Street just south of Constitution Avenue. The other is on 17th Street, where the Potomac Park Levee gives out before the land starts rising toward the Washington Monument. As with many urban levees, roads that pass through it have to be closed off as a storm approaches. When the Potomac is about to flood, the Park Service is supposed to block the 23rd Street gap with sandbags and concrete barriers. Filling the 17th Street gap is more problematic.

“We’re not satisfied with the procedures that would be taken to block 17th Street,” Vidal says.

Plans call for a temporary earthen dike eight to ten feet tall to be built when a big storm is headed toward Washington. The key, says Michelle Desiderio of the National Capital Planning Commission, “is having enough time to put that levee into place to prevent overbank flooding from getting into the downtown area.”

The Army Corps of Engineers has been asking Congress for funding to fill the 23rd Street gap permanently and prepare a dependable closing structure for the 17th Street gap. Vidal would like to see an underground foundation built across the 17th Street gap with regularly spaced postholes. As a storm approached, posts could be inserted to support panels that would hold back the water. The levee would protect property worth billions of dollars. “Now we’re just waiting for the funding,” Vidal says.

For most coastal cities, levees will be the first line of defense. Especially if the current rate of sea-level rise accelerates, cities around the world—including Washington—will have to surround themselves with levees to fend off floods. A couple of centuries from now, the Mall could look like the Naval Air Station does today, with its monuments separated from the river by a 12-foot levee.

It’s not a very elegant solution. For one thing, levees can fail. Already, the Potomac Park and Anacostia levees are on a list of 122 levees around the United States that the corps has identified as needing improvements. “As you might expect,” Vidal says, “our levee-inspection program has been getting a lot of attention.”

The more serious problem may be aesthetic. If levees are built around the Mall, future tourists will gaze not at broad vistas of rivers and hills but at a ring of embankments. The same will be true everywhere levees are built. Says the University of Maryland’s Kearney: “People come to Ocean City to see the ocean, not the backside of a levee.”

Take the Category 3 hurricane that Kearney fears and aim it at New York City—right at the crook where New Jersey and Long Island funnel the Atlantic Ocean toward Manhattan. The result could be a natural disaster greater than Katrina.

Large parts of Manhattan, Long Island, and New Jersey would be inundated; flooding along Canal Street would cleave Manhattan into two islands. Water would pour into the subway and traffic tunnels, drowning anyone inside. Underground electrical and data lines would be destroyed. One projection puts the estimated damage at $100 billion.

There’s a way to prevent almost all of that damage, says Malcolm Bowman, an oceanographer at Stony Brook University. Build gigantic floodgates between New Jersey and Staten Island, between Staten Island and Brooklyn, and between Queens and the Bronx. As a hurricane approaches, the gates could be raised to create a vast dike around the city.

If big floodgates are good enough for New York, why not build them for Washington? Floodgates on the Potomac River south of DC could protect the city from hurricanes, nor’easters, even high tides. A more ambitious plan would be to build a barrier all the way across the 18-mile mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, protecting every city from Baltimore to Norfolk.

Floodgates may appeal to our desire for quick fixes, but they bring lots of problems. They can seriously impede water traffic. The freighters, cruisers, and tankers that now ply the bay would be blocked whenever the gates are closed. Large ships could lose access to the bay altogether.

Also, the cost would be high. Bowman thinks the public would agree to the expense only after a major storm, but that would mean paying twice—once to repair the initial damage and once to prevent future damage.

Floodgates can’t be raised all the time—at most, they would be a temporary expedient if sea level rises substantially. If they were raised permanently, the bay would soon become an open cesspool as the toxins in the Susquehanna, Potomac, James, and other rivers accumulate behind the gates. Also, the combined flow of the rivers would have to be pumped over the top of the floodgates, requiring massive pumping stations.

What’s more, I don’t know how comfortable most people would be living beneath a dam that has the Atlantic Ocean behind it. Any such structure would need to be guarded more tightly than a nuclear power plant: A single rowboat packed with explosives could put the nation’s capital underwater.

Given all the objections, are floodgates realistic? Perhaps a better option would be to take steps to limit sea-level rise—as hard as those steps might be—or start thinking about how to move coastal cities.

Other cities and countries have built floodgates, Bowman observes. Huge gates on the Thames River protect London from storms and high tides. Half of the Netherlands lies below sea level and remains dry only because of a massive system of dikes, levees, and floodgates.

No one is talking about building floodgates anytime soon. Still, the fact that they’re being considered suggests the magnitude of the problem. “We’re just trying to do some consciousness-raising,” Bowman says. “At least people aren’t laughing at us. They could have said we’re crackpots, but they’re not saying that.”

If sea level rises so drastically that the Mall can’t be protected, the monuments will need to be abandoned, torn down, or moved.

It seems inconceivable that they’d be abandoned. The monuments were built to last hundreds or thousands of years, like those of Greece and Rome. They could be torn down and rebuilt elsewhere, but even dismantling them could be traumatic. Could they be moved intact?

I caught up with Jerry Matyiko, owner of the Maryland branch of Expert House Movers, at American University, where he was preparing to lower a concrete floor the size of a basketball court as part of a renovation project. “Anything is movable,” he said. “It’s a matter of what you can get down the street.”

Matyiko’s company has been moving plantation houses, museums, auditoriums, and everyday split-levels since his father founded it in 1955. Matyiko’s greatest accomplishment: He was a lead contractor in the move of the 4,800-ton Cape Hatteras lighthouse half a mile inland to protect it from rising seas.

Still, he looks at me skeptically when I ask if he could move the monuments. But then he says he could: “After all, we moved the lighthouse, and that was 200 feet tall. But you need to want to move something. And you need to have the money.”

Money is often the stumbling block in responding to sea-level rise. Cities can be picked up and moved to higher ground, but who’s going to pick up the bill? The Cape Hatteras lighthouse, which cost $115,000 to build, cost $10 million to move. Moving the monuments—much less the rest of downtown DC—would be monumentally expensive.

Say that all the ice on Antarctica melted, not just the western-Antarctic ice cap. In that case, sea level would rise at least 200 feet. Every coastal city in the world would be destroyed. Just the top half of the Washington Monument would extend above the Atlantic Ocean. The new East Coast would cut across the lawn of the Vice President’s house on Massachusetts Avenue.

No one expects all of the ice on Antarctica to melt. The continent has had an icecap for millions of years. Summertime high temperatures at the South Pole are 19 degrees Fahrenheit below zero—far too cold for substantial melting to occur. There’s even a possibility that Antarctica’s icecap could grow if more snow starts falling on the continent, which could draw water from the oceans.

But the most likely prospect is that sea level will continue to rise as the world warms. At first the rise will be moderate—an inch or so a decade. Later it will accelerate. And if the Greenland or western-Antarctic icecaps start to melt, the oceans could rise quickly.

Human civilization has been lucky. Sea level remained essentially stable from the time of ancient Egypt until the 19th century, when humans began to burn large quantities of fossil fuels. That period of stability is over. Maybe scientists will figure out how to control earth’s climate so as to regulate the amount of ice on Greenland and Antarctica. More likely, our descendants will have to learn to adapt.

“It’s going to take a mobilization like that of World War II to deal with this problem,” Kearney says. “We have the money to save historic areas, but tough decisions will have to be made because there’s not enough money to save everything. And the longer we wait, the more expensive it will be. Nothing gets cheaper.”

Maybe the seas’ rise will continue to be moderate. Maybe cities and countries will be able to build seawalls, levees, and floodgates to hold back the water.

There’s one thing we know for sure: As sea-level rise becomes a greater problem in the decades ahead, our descendants will ask why we didn’t do more to prevent it.