Halina Yasharoff Peabody is shrinking.

Once just over five-foot-four, she hasn’t reached that mark in years. Her hair is blond and, as women once said, set with a high comb, reclaiming a bit of that lost height. Her eyes are a sharp blue-green. The voice is low but commanding, with a hint of a sophisticated, hard-to-place, European accent as 47 Catholic-school eighth-graders lean in, dwarfing her.

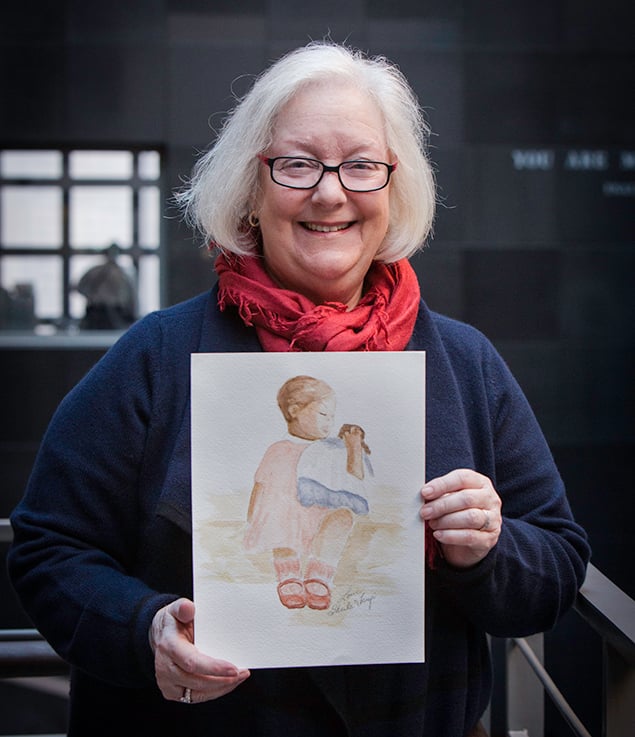

For the last decade or so, Halina has spent her Thursday afternoons holding forth on the main floor of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Behind her, a black marble wall is engraved with the phrase “You are my witnesses.” A smaller sign on her desk announces: “Speak with a Holocaust survivor.”

Vivacious, Halina could pass for an older baby boomer. She is, in fact, 82.

A girl raises her hand. “What was it like to be in a concentration camp?” she asks.

Halina explains, patiently, that she wasn’t in a camp: “The Nazis had no use for seven-year-olds.” They murdered children who arrived in camps. Halina’s mother successfully hid her and her baby sister’s identities in Poland.

“Were you scared you would, like, be killed?” asks a girl wearing an Air and Space Museum sweatshirt.

“Yes, exactly,” says Halina, hiding her hand in her lap, the hand that’s missing a thumb and half a pinky finger. They were torn off in the last moments of the war, when her safe haven was bombed.

Stories like Halina’s—as much as the permanent exhibit, with its cattle car and its piles of shoes from the Majdanek camp—may be the most affecting part of a trip to Washington’s Holocaust Museum. Yes, there are miles of documents, artifacts, and other materials. And hundreds of hours of testimony recorded in the library. But at a time when 90 percent of the museum’s 1.6 million annual visitors are non-Jews and an even higher proportion are too young to remember World War II, nothing humanizes the history like a survivor.

And that’s a problem.

Even those who were children during the war are now approaching or well into senescence. Fewer and fewer adults are around to speak to groups. It’s an actuarial issue that presses down, insistently, on the museum. Born in 1932, Halina—just six when Hitler invaded Poland—is still part of a generation of “survivor volunteers” that is passing from the scene. The question of what happens when they’re gone will determine a lot about the museum, and our teaching of the Holocaust, in the decades to come.

In September, I made an appointment to visit the museum to discuss its plans for a post-survivor era. But the night before I was due, Diane Saltzman, the director of survivor affairs, e-mailed regrets. She had to reschedule—she’d be attending a funeral for a survivor volunteer, her fourth this year.

Those volunteers have, from the beginning, been a part of why the Holocaust Museum—which opened in 1993, nearly a half century after liberation of the camps—has been viewed as such a stellar institution. From the outset, this was a place of storytelling as much as artifact collecting. It was a living memorial, one that strove to show survivors not just as the persecuted but as people with lives before the war and after.

Nowadays, the museum is hardly unique in leaning on the memories of individuals: Holocaust educators from Tel Aviv to Paris to Argentina to Australia rely as much as they can on eyewitnesses. German towns often import them, inviting back those who fled. There are survivor-led tours of Auschwitz. This practice may seem obvious today, but it wasn’t always so.

“In the first years, postwar survivors weren’t considered trustworthy,” says Jean-Marc Dreyfus, reader in Holocaust studies at the University of Manchester in England.

While there was some immediate postwar gathering of material—in displaced-persons camps, before the Nuremberg trials, before the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961—the majority of survivors didn’t speak for decades. In part, this was because no one was asking, let alone planning for ways to preserve their audio and video testimony. “They were considered biased by trauma,” says Dreyfus. “There was a radical change in the 1970s—it came from the United States and was eventually exported to the rest of the world.”

In this new thinking about how to arrange historical exhibits, the shared trauma actually imparted a great deal to the listeners. To hear Dreyfus tell it—and to watch the schoolkids gathered around Halina Peabody’s desk—there’s almost a holiness about the experience of meeting a survivor. “It’s not only what they say—it’s their physical presence,” Dreyfus explains. “They are effective even if they don’t say anything.”

At the Holocaust Museum, the survivor volunteers do more than serve as eyewitnesses. Many are multilingual, in languages that span the breadth of the Nazi occupation of Europe, and they translate everything from oral histories to documents. Others provide crucial context for the photo archivists, the sort of identification nearly impossible without the help of someone who was actually there. Yet even from the beginning, there was anxiety about eyewitnesses’ role. “The discussion has gone on for decades,” says Dreyfus. “ ‘What will we do without them?’ ”

The Claims Conference, which keeps statistics on Holocaust survivors, estimated that, as of late 2013, some 160,000 were left in the world. The number sounds high but includes many people too ill to offer testimony or too young to remember much. The population of people able to describe certain specific experiences has dwindled to almost nothing. For example, as the Wall Street Journal reported in 2013, out of 850,000 people sent to Treblinka, just 67 survived the war—and only two are still alive.

“Often I get the question ‘What will replace the survivors?’ ” says Sara Bloomfield, the Holocaust Museum’s director. “Nothing will. It is not the right question. The real question is: How do you make sure the Holocaust is relevant to new generations, knowing not only that the Holocaust will have receded in time but also that there will be no more World War II soldiers or survivors?”

One answer: survivors’ own children. At the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York, curators have begun to train second- and third-generation survivors, people still tethered to the loss by virtue of having grown up with survivors. Technology is also part of the fix. At Washington’s museum, a video bank serves as a bulwark against the future. The USC Shoah Foundation, bankrolled and backed by Hollywood director Steven Spielberg, recorded some 52,000 interviews with survivors, most of which are viewable in the library.

Even now, the Holocaust Museum is dipping into the trove of oral history already on hand. For the current exhibit “Some Were Neighbors,” which homes in on moments of betrayal, curators didn’t turn to survivors for video testimony; they used previously recorded material, a marked contrast to the exhibits of the ’90s. “In the past, we always did our own interviews, which was great—we composed questions pertinent to whatever the topic was,” says special-exhibitions curator Susan Bachrach. “But the reality now is there just aren’t enough people around anymore.”

Elsewhere, less conventional technology is being brought to bear. At the University of Southern California, survivor testimonies are being turned into holograms that will someday be able to, theoretically, “respond” to questions “naturally,” like Princess Leia appealing to Obi-Wan in Star Wars.

Meanwhile, the museum’s other work—collecting letters, photos, material goods, clothing, anything that can be woven together with the witnesses’ words to create a narrative that explains lives—continues with a new urgency.

“We know the window of opportunity is closing fairly fast,” says curator of art and artifacts Suzy Snyder. “It’s virtually impossible to not pick up a newspaper to read about a survivor on a weekly basis who’s passed away. It’s hard for the staff, but it encourages us to bring in collections. If you acquire from survivors and you have questions, they can answer them, where often their children can’t tell you the things you really want to know. Sometimes survivors didn’t talk [to their kids]. Sometimes people speak more easily to a stranger than to their children.”

Likewise, sometimes people ask a stranger questions more easily than they do their parents. Especially in the first decades after the war, there was a sense, among some of those born to Holocaust survivors, that it was best not to press too hard, just as there was a feeling, among a handful of survivors, that it was best for their children not to know. That silence means that it’s often hard for descendants to narrate the experience, or the artifacts, of their parents fully.

The youngest survivor volunteer, 72-year-old Louise Lawrence-Israëls—who was hidden in a Dutch apartment from six months to nearly three years old—gave the museum a child’s chair. Why? Because it was the one she sat in while in hiding. No one would know from looking at it. But there’s one photo, taken by a friend of her parents, of her as a small child in her attic hideaway, in that same chair. Without her testimony, it’s just a chair.

If the end of the survivor era represents a challenge for people who oversee the museum’s programming, it also raises a bigger philosophical question of what a Holocaust museum should do. Should it be about genocide and hatred in general or about one specific piece of history?

Early on, the founders decided their job was to commemorate a particular moment in time, with real people—not a metaphor for evil but a series of events and the stories of individuals caught up in them. A Center for the Prevention of Genocide, nestled within the museum’s labyrinthine offices, would organize calls to action on behalf of other persecuted peoples. But for the most part, the actual exhibits would stick to history.

“We talk about relevance all the time,” says Bloomfield. “How are we relevant for an audience? We know the relevance that comes through authenticity—that is the survivor. But there is also the relevance in that the topic connects to my life.”

These days, that type of relevance is becoming more prominent. Exhibits have a broader focus, asking the big questions. Instead of the ’36 Olympics, now it’s why did the Holocaust happen? What could have been done to prevent the genocide? And what lessons can we draw from history? An exhibit called “Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race,” for example, went up during the national debate on cloning. Another, on propaganda, played off the idea of the rise of the internet and the spread of hate.

A bigger change—say, expanding the museum’s central focus to include stories from Rwanda or Bosnia—would be deeply controversial, and Bloomfield says it has never been considered. Other tragedies may merit chronicling, and other eyewitnesses may be easier to find, but the museum’s primary job is to document what happened in Hitler-era Europe.

To best understand the Holocaust, almost all of the staff I spoke to at the museum emphasize, the big ideas remain the same: making sure visitors don’t see victims as only victims but as people who lived full, recognizable lives before the war. And, second, that the perpetrators and onlookers aren’t portrayed simply as monsters but as neighbors, friends, regular people. In-person survivor testimony may be the best way to achieve that, but it isn’t the only way.

“We are, you know, a finite group,” Halina Peabody told me by phone some weeks after we met. “They will do their best to carry our memories. We have given our pictures, our papers. They can’t make us live longer than we are going to. They are there to make people understand what can happen if we are not vigilant. And in my family, the second and third generation is also working very hard to learn our stories. My granddaughter, for instance, says she will make a movie.”

It’s always easier to relate to Halina and her personal tale than to hear of an entire village wiped out. In part, that ease comes from allowing visitors to see themselves in the story. Anyone who has been through the museum’s extensive permanent exhibit knows that the ending is a series of vignettes told by survivors themselves. It’s incredibly powerful. It was also filmed, for the most part, years ago. Today, survivor testimony has already changed. Those who lecture on the floor of the museum are telling stories of their childhood. Their parents have already left us.

Toward the last moments of Halina’s day, as she packs up her materials and arranges to head home, a woman wanders over. “I was here some years ago, and my daughter got to meet a survivor!” she exclaims. “And I missed it!” She’s thrilled to finally have her chance.

Halina smiles. “It makes the history more real,” she says. “As long as we are here, we have to continue.”

Sarah Wildman is a frequent contributor to the New York Times. Her book, “Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind,” Came out in October. Her website is sarahwildman.com.

This article appears in the January 2015 issue of Washingtonian.