What’s the human cost of social progress? What happens to a person who all of a sudden is thrust to the forefront of the national conversation, whose entire life becomes a metaphor for a cause?

These are some of the issues considered in Rodney King, Roger Guenveur Smith’s one-man show currently playing at Woolly Mammoth as part of the Capital Fringe Festival. Smith, who created the show, has made something of a habit of these solo treatments: In the past he’s taken on such figures as abolitionist Frederick Douglass, baseball players Juan Marichal and John Roseboro, and Huey P. Newton, the cofounder of the Black Panther party (Newton’s story became an award-winning TV movie). In King, Smith focuses on the African-American construction worker who was viciously beaten by Los Angeles police in 1991; film of the assault and the acquittal of the police officers involved by an all-white jury led to rioting and violence in LA that resulted in the deaths of 53 people and transformed everyman King into a symbol of race relations.

King led a troubled life both before the incident that made him infamous and after, including issues with domestic violence and substance abuse, and he eventually drowned in his own swimming pool on Father’s Day 2012. His tragic end became the impetus for Smith to develop this work, and he doesn’t shy away from the flaws of the man at the center of the story; he’s fascinated by the contrast between the real Rodney and the media-constructed one, and there’s a sense of the artist struggling to live with and understand someone else’s demons. Smith has described the piece as “a series of questions, not unlike a postmortem interview with Rodney King,” and he improvises almost all of each performance, taking on the cadences and inflections of a slam poet. It adds a fascinating layer—the audience can actually see the artist working through his thoughts and emotions and coming to new understandings—but the loose structure means the show sometimes meanders from one point to the next.

Smith arrives at no clear answers or sweeping realizations, though the point of the performance seems more to crystallize emotions and impressions than to find anything resembling a solution to the deeply entrenched societal issues the play touches on. Still, there’s plenty of pointed criticism: Smith at various times skewers the media, the police, even the audience, following a chuckle-earning line with the observation, directed at King, that people now see him as a joke. Throughout it all there’s a constant refrain of “Right, Rodney?,” a phrase Smith delivers in tones alternately compassionate, quizzical, and condemnatory. At times, he seems to understand King deeply; at others, he’s still grasping for answers.

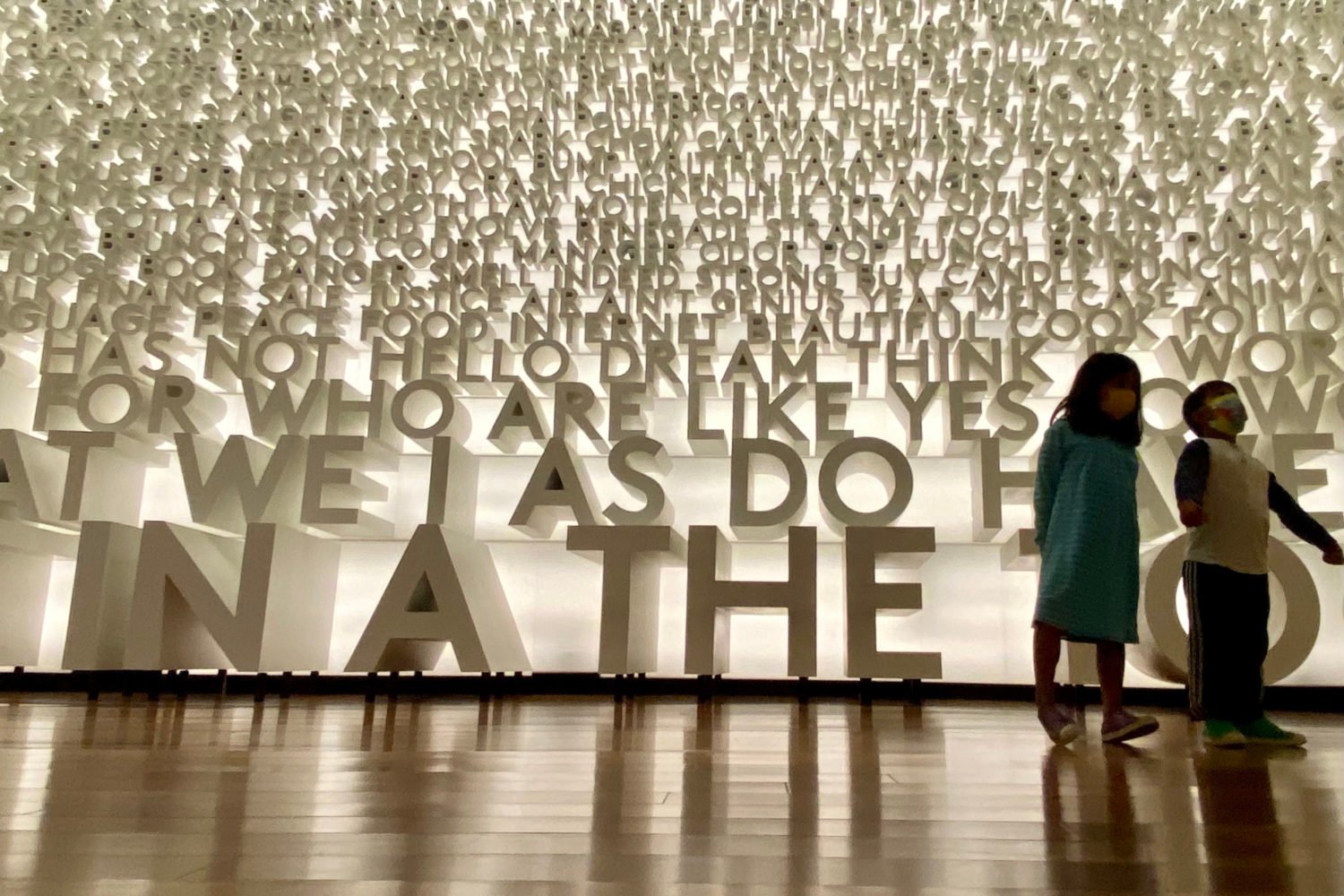

The set is bare-bones, and Smith—barefoot, dressed in a black T-shirt and jeans—relies on only occasional sound and lighting effects to enhance his performance (lighting by Jose Lopez, sound by Marc Anthony Thompson). The simple staging is a smart choice, stripping away anything that would take the focus off the subject at hand. It also provides an interesting contrast with Smith’s declaration that King is the “first reality-TV star,” invoking a medium that thrives on artifice and edited-in drama.

King’s tale is a toxic stew of race relations, the corrosive power of media, and the struggle of an ordinary person who suddenly finds himself living very much in the public eye. While Smith touches on many themes—the constancy of violence, the way vices and fates seem to pass down from one generation to the next—he steers clear of inflating King’s life to mythical proportions. Toward the end of the play, in one of the few non-improvised moments, he recites King’s famous speech, pleading to the audience, “Can’t we all get along?” It’s such a simple statement, almost childlike—but, much like its utterer, in context it becomes symbolic of so much more.

Rodney King is at Woolly Mammoth through July 20. Running time is about one hour and ten minutes, with no intermission. Tickets ($35) are available online.