Nine thousand miles from home, Carl Hoffman sat cross-legged in a wood hut in northwestern New Guinea, facing 40 silent, barefoot men in ill-fitting T-shirts. He’d come to solve the disappearance, 50 years earlier, of a scion of one of America’s most famous fortunes. But after spending weeks losing weight on a diet of ramen, fish, and sato, made from palm trunk, and making no progress, he realized he’d been arrogant. He’d hoped that these people, the jungle-dwelling Asmat, would share one of their most closely guarded secrets. But as an interpreter relayed Hoffman’s questions, the men simply stared back.

Their silence, it turned out, was part of the answer.

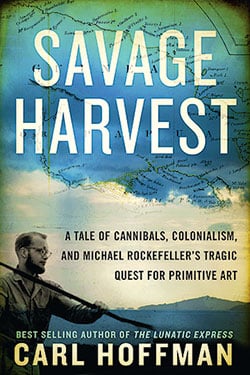

A Washington native, Hoffman has spent his career as a magazine writer and author reporting from the “nooks and crannies of the world,” as he puts it, with DC serving as his base. Most mornings he can be found writing at Tryst in Adams Morgan or at Big Bear Cafe, near his home in Bloomingdale. In stories for Smithsonian and National Geographic Traveler (where he’s a contributing editor) and in his books, 2001’s Hunting Warbirds and 2010’s The Lunatic Express, Hoffman has indulged his fascination with the world’s overlooked, such as migrant workers in Southeast Asia, and with solitary adventurers taking refuge from the West. In his new book Savage Harvest,he writes about both these kinds of people, or rather the collision between them.

It’s the story of Michael Rockefeller, who traveled to Dutch New Guinea in 1961 to buy “primitive” art from the Asmat, a people with a rich artistic tradition inextricably bound up with the practice of cannibalism.

Rockefeller was just 23 when he vanished while attempting a rough ocean passage in a motorized raft off the coast of the Asmat’s densely forested territory. After an intensive and fruitless search, he was presumed dead by drowning and the case was officially closed. During the search, press reports emerged claiming Rockefeller had swum to shore, only to be killed and eaten by the Asmat. These accounts were later refuted by the Dutch colonial government, but the story persisted. It has since become the subject of a number of TV shows and books.

Savage Harvest, perhaps the first serious and comprehensive work on the topic, argues compellingly that reports of Rockefeller’s cannibalization were true.

• • •

In the hands of another writer, the tale could have become the tragic biography of a privileged young man, with the Asmat serving as exotic props. But Hoffman’s book is the opposite. “I’m really not interested in the Rockefellers,” he says over coffee at Tryst. “It was the Asmat I wanted to write about.” The Rockefeller story was, in a sense, just an excuse.

Hoffman’s original idea was to travel through the villages of Asmat, like Rockefeller, reporting on his experiences and the people he met along the way, as he had for The Lunatic Express. For that book, Hoffman traveled the world on the most dangerous ferries, trains, and planes, the conveyances of the striving poor. The most affecting passages are his reportage on the lives of friends he made in the packed hulls of ferries and the fetid cars of desert trains.

Hoffman’s intention for Savage Harvest was to explore a radically different world and the humanity of those who inhabited it. In the process, he’d try to figure out what happened to Rockefeller, but, he says, “I told the publisher that if they were depending on me to solve the mystery, they couldn’t buy the book.”

Nevertheless, Hoffman took the investigation seriously. He was troubled by the lack of evidence suggesting that Rockefeller had drowned: “I was unconvinced that anything had been done that was smart and substantive.”

With the help of a researcher, he scoured European archives for the letters of missionaries and Dutch colonial officials working in Asmat in the 1960s. As he read, the evidence began to point away from drowning. One chilling report by a Dutch missionary who had investigated Rockefeller’s disappearance concluded, “It is certain that Michael Rockefeller was murdered and eaten.”

• • •

By the time Hoffman arrived in New Guinea in February 2012, his view of the book had changed. “I started believing there was a complex story” about Rockefeller’s disappearance, he says. And he thought he might be able to untangle it.

The only obstacle was Asmat itself. By Hoffman’s count, he has traveled to more than 70 countries, but he’d never been anywhere as remote or foreign as Asmat. He moved through the region carefully by boat, accompanied by five men—including a guide and an interpreter—and rarely spent more than a few days in one location.

Perhaps no place unsettled him more than Otsjanep, one of the home villages of the men suspected of killing Rockefeller.

“The vibe here felt strange,” Hoffman writes of his arrival. “Dark. Oppressive, as if there were something hanging over the village. . . . I looked at people and they looked back, but there was no recognition, no welcome, nothing that drew me to them. No one shook my hand. No one invited us into their house. I felt like I had no traction here.”

There was also the specter of cannibalism, no longer practiced but informing Asmat culture. The place “made my hair stand up,” Hoffman writes, and he left after only a few days.

Following two months in New Guinea, he returned to Washington with new information about Rockefeller, but he decided he didn’t have enough. To finance a second trip, he sold German rights to the book and raised thousands through a Kickstarter campaign. Meanwhile, he learned Indonesian, one of the languages spoken by the Asmat.

In November 2012, he pulled up to the banks of Otsjanep again, without a guide or interpreter but with plans to stay awhile. He unloaded sacks of ramen noodles, rice, and tobacco—gifts to ingratiate himself with the village elders. He told the driver of the boat to come back for him in 3½ weeks if he didn’t hear from him.

Then he abandoned himself to life in the village. He ate what the Asmat ate, including roasted beetle larvae. He bathed alongside them in the river, downstream from the neighboring village, and when his bottled water ran out, he drank water collected from village roofs. He spent days sitting around, just watching, smoking, and making himself available to anyone who wanted to talk.

As the weeks passed, people began to divulge crucial information about events preceding Rockefeller’s disappearance, including the murder of several Otsjanep men by a Dutch officer. In the Asmat cosmos, in which deaths must be avenged to maintain balance between warring factions, these events represented a clear motive—or rather a “sacred obligation,” as Hoffman came to understand it—for cannibalizing Rockefeller and for maintaining a determined silence on the matter thereafter. The discoveries were a breakthrough, and the culmination of what Hoffman admits was the hardest project of his career.

It was a humbling project, too. As he researched the book, he found that one of Rockefeller’s mistakes, one of the things that did him in, was his failure to dig deep and establish a relationship with the Asmat.

“I’d been guilty of the same sins,” Hoffman writes of his first trip, “. . . passing through Asmat too quickly, assuming that I was so important that I could pepper them with questions and out would pour their deepest secrets . . . .” The Asmat are profoundly different—“the strangest people I’ve ever seen,” he writes. And though ultimately he established some rapport with them, doing so required a willingness to experience Asmat on their terms, not his.

Hoffman learned this lesson and was able to redeem himself on his return trip. Rockefeller wasn’t so lucky.

Michael Damiano (mjdamiano@mac.com) is the author of “Porque la Vida No Basta,” a biography of Spanish painter Miquel Barceló. This article appears in the March 2014 issue of Washingtonian.

Author:

Carl Hoffman

Publisher:

William Morrow

Price:

$19.19