By Alexandra Dell

I picked up my first tennis racquet at age three. It wasn’t by choice; it was just one of those things my father, Donald Dell, a former Davis Cup captain, was hell-bent on “exposing” me to. But considering that tennis was his job and I had been traveling to pro tournaments with him and listening to the smacking of that yellow ball, like popcorn popping, since I was born, I was pretty sure I already had been “exposed.” When he gave my sister, Kristina, and me child-size Jack Kramer racquets for our fifth birthdays, Kristina held hers up, wrinkled her nose, and said, “How about a pony?”

I resisted learning the game from an early age. Instinctively I knew that for me tennis was never going to be about the simple joy of whacking around a fuzzy yellow ball. Instead, it would always be tied up in family expectations.

After a year of disastrous lessons and family rifts, my father decided my sister and I needed a real teacher, someone we would listen to. He called up the Terminator of tennis pros, the legendary Nick Bollettieri. Sending your kid to Nick to learn tennis is a bit like sending your little tumbler to that burly gymnastics coach with the handlebar mustache who gives little girls bear hugs while he makes them into Olympic champions.

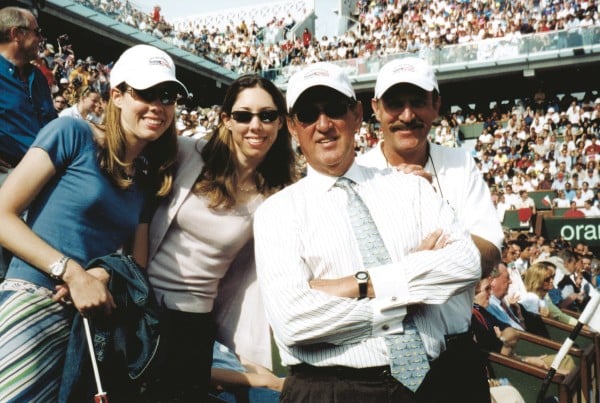

We met Nick at the Colony, a tennis resort near Sarasota, Florida. When we arrived, we found him finishing up a lesson with Carling Bassett, a leggy blond knockout from Canada. Nick was pushing my dad, by then a sports agent, to represent her. She would be going pro within the year, Nick told us. He ended the lesson by having Carling hit a series of overheads, a showboat-type shot he had chosen to display her graceful form and golden potential. She would up and hit every one into the bottom of the net.

Photograph courtesy of Alexandra Dell

For a second, I felt bad for her. The chance to pity the beautiful, awe-inspiring Carling Bassett, if only for a moment, made me feel like a winner, and I loved her for it. I wished she would keep missing, to bring down expectations, so that when I got out on the court I wouldn’t look so pathetic, but I knew that the alien who had possessed her arm would give it back at any moment.

“Carling, daddy’s darling, what is going on, dear?” Nick yelled from the baseline. “Donald, I didn’t teach her that one!”

Nick had his sunglasses on and his shirt off. When he did wear clothes, they had his name emblazoned on the front so that he was a moving advertisement for the Bollettieri Tennis Academy. He was a bronzed marketing genius with a little sprout of a mustache and brown hair. The irony was that he could teach the perfect strokes, but he couldn’t hit that beautiful topspin forehand he taught and he never actually played with any of his students. Instead, he would squat like an umpire behind the baseline to get a full-body view of his player, yelling catch phrases in his raspy voice: “Cen-ter, cen-ter! Easy, dear! Eye on the ball, dear! Head up! Pret-ty! Move your feet! Ea-sy, ea-sy! Cen-ter! That’s right, dear!”

Nick coached Carling out of her little slump right back to perfection. She hit a few winners and then called it a day.

“Ohhhh, Donald, in all my days, I’ve never seen a kid like this,” Nick said, retreating to the sidelines for a cup of water. Nick spoke only in superlatives. “This kid’s gonna be great. Number one. And I’m not talking Canada. The world, Don, the world. They just don’t make ’em like this.”

My father kept nodding as if he had strapped on a bobble-head.

“She could make the cover of Playboy without her racquet, Don,” Nick said. “Ah, I knew that would get you.” When he ran out of Carling compliments, Nick turned to my sister and me: “So let’s see what you’ve got, kids.”

Kristina and I walked to the baseline in our matching Superman sneakers that weren’t even tennis shoes, dragging our racquets on the ground behind us. Nick wanted to teach us together; he thought we could learn by watching each other. I wanted to tell him that you can’t learn by watching someone else who can’t play, but I thought it was best to keep quiet. After a swing and a miss again and again, he told us to move up some on the court.

“Easy, dear. Eye on the ball, dear. Pret-ty. Pret-ty. There you go. Uncle Nick is right behind you.”

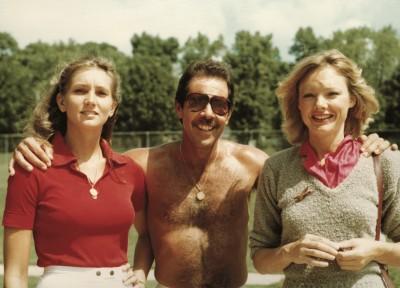

Photograph courtesy of Alexandra Dell

Nick treated the lesson as if we were on our way to the finals of Wimbledon, and it made me feel good that he was using the same words to yell at me that he had used on Carling. By the end of the lesson, I had made contact not only with Kristina but with the ball. I felt like a champion. Nick gave us Bollettieri T-shirts and told us to keep practicing and to squeeze a tennis ball every night before we went to bed to build up our wrist strength. That wasn’t happening, but it was a good idea, probably why Carling had such a great kick serve.

My dad chalked up the week with Nick as a big success. He started calling me DonaldAnna, in place of the boy he never had. But once Nick wasn’t there, neither was our desire. Kristina still wanted a pony. I liked going to gymnastics class.

“Where is gymnastics going to take her?” my dad asked my mother, Carole. “Is she going to somersault her way into a college scholarship?”

So a year later he again called up Nick, who by now was doing pretty well because Carling was winning everything. Dad was happy too, because he was representing her.

“We don’t have any room at the academy right now, Donny boy, but why don’t you just have your kids stay at my place?” Nick said, never one to turn down any form of business. By now we were eight years old.

Nick’s wife, Kellie, greeted us and showed us around the house, which was in the tennis complex. She was Nick’s fifth wife, a tall brunette half his age, with a hospitable charm. She set us up in a room right off the house with two single beds and Bollettieri posters all over the walls. Nick was outside working, shirt off, sunglasses on, slathered up in oil like a slippery dolphin. He had moved his desk outside in the yard to maximize the sun time while he worked.

“Hey, kids, come give Uncle Nick a hug,” he said. “Have you been squeezing those yellow balls?”

Jimmy Arias and Aaron Krickstein, who would both go on to become top ten in the world, were out playing when we arrived. Carling even had dated one of them, as if only the best of the best could interbreed; anyone else would have brought down the gene pool. A crowd had gathered to watch Jimmy and Aaron as they slid the ball low over the net, deep into the corners of the baseline.

Kristina and I took the court next to them to be evaluated, to see what group we should be in. Some of the crowd moved over to watch us, thinking that we too must have lots of potential. “These are two to really keep your eye on,” I imagined them saying.

We started out in a medium-talent group but kept moving down throughout the day as the other kids kept beating us. Eight hours of tennis and several blood blisters later, Kristina and I came back to Nick’s house a bit defeated. We found him in his wall-to-wall mirrored workout room doing sit-ups. Seeing the sadness on our faces, he launched into his pep talk. “Dedication. Discipline. Drive. Determination. The four D’s. That’s my motto,” he said. It was his motto; I had seen it written on some of his Bollettieri T-shirts.

“You’ll get there,” he continued. “You both have great potential. I wouldn’t be working with you if you didn’t.”

Photograph courtesy of Alexandra Dell

I don’t know whether he was lying or simply knew they were words we needed to hear, but I appreciated them. It was then that I understood why this man who couldn’t play tennis very well was the best coach in the country. By treating two tennis misfits with the same intensity as he did the world-class champions hitting on the court next to us, he gave us the confidence to think we could be good.

“Now come give Uncle Nick a big hug,” he said, his reflection glistening from every angle in the wall of mirrors.

Kristina and I continued playing tennis throughout grade school, spending a couple of weeks every summer at Nick’s academy. And we did improve. By the time I got to Bethesda’s Holton-Arms and Kristina to Stone Ridge, we actually started to love the game, playing junior tournaments.

My dad would play with us as often as he could, acting as our surrogate coach, though we’d usually do the opposite of anything he said. He loved to watch my sister and me play in high school. He’d sneak up on us, unannounced, in the middle of our game and yell tips at us, like some disembodied voice from above.

“You’re late on your forehand, Alexandra!” I’d hear from somewhere in the trees and then see him peeking through the fence.

“God, Dad, I know!” I’d yell back. “Stop spying on us!”

Tennis at Holton was the first time I was able to enjoy the game in a social way. Playing on a team with friends was a nice break from the pressures and solitude of junior tournaments—except when I was forced to play my sister. We both played number one for our school teams, and when we met each other late in the season, our matches always ended in tears and silent treatments and, once we were in the car, the kind of hair-pulling fights you get into only with a sibling.

For college, Kristina and I both chose Yale, my father’s alma mater, because we liked the team and the coach and never wanted to play each other in a school match again, though neither of us anticipated the pressure of coming in as daughters of Yale’s greatest tennis player.

We had eight freshman recruits come in that year. I was on what you might call the B team. I never actually played in a real match my freshman year, but I sure did practice a lot. I would wake up early. Play before practice. Play after practice. Need a hitting partner? Sure, I’m available. I was that eager beaver the top players love to hate, the one who’s always playing. But I was determined to improve.

Over Thanksgiving, my family spent the weekend with the Smiths, a tennis family. “So Alexandra, what number are you playing at school?” Stan Smith, the former Wimbledon and US Open champion, asked.

I stalled by tying my shoe. I figured my mom would blab the truth to Margie, his wife, anyway, so there was no point in lying. “Oh, about number 12,” I mumbled.

Stan looked confused. “Do they have 12 people on a team these days?” he asked. “When I played, there were only six players in a lineup.”

“Yes, technically that’s still true in tennis today,” I said. “But we need alternates. Lots of injuries can happen.”

Stan knew enough not to press the issue. “So,” he asked, “how are your grades?”

Toward the end of freshman year, I played in a few alternate matches at the number-seven spot. All the practicing had helped me claw my way from the very bottom to the top of the bottom. These matches at number seven didn’t count for anything. The two benchwarmers would duke it out against each other for sheer love of the game. My coach, Becky, a blond, good-natured, very relaxed soul who was into new-age medicine and self-help books, was happy to put me in a match just so she didn’t have to hear from my father.

My dad came to every one of these practice matches, yelling tips at me through the fence. “Change a losing game!” he said as I sat down on a changeover while getting pummeled by a big, buxom Princeton girl. “Becky should be over here coaching you!”

“Dad,” I yelled back, “the match doesn’t count!”

“It counts if you want it to count! It counts for your pride!”

The Princeton girl knew she had this one in the bag.

By sophomore year, some of the former freshmen who had been our top recruits had gotten injured. Their delicate, fine-tuned frames couldn’t take all the drinking and partying. Now was my chance. I was actually going to play in a real match at number six.

My father was so excited that he flew back from Tokyo early and drove from the New York airport to see my sister and me play. Kristina was playing number five. This was my father’s dream—his two daughters playing for Yale. In matches that made the scoreboard.

To get loose before the match, our coach had us do a series of sun salutations on the side of the court, a yoga position she was fond of that entailed lying flat on our bellies and lifting our trunks and then our butts straight up in the air.

My father was not happy with these newfangled warm-up techniques. “You all look like idiots out there. I would pray I was playing your team,” he said, taking me to the side of the court. “Is Becky having personal problems?”

I think Kristina and I both won our matches that day, but Yale got smoked by Penn. While we were disappointed, Dad was beside himself. He caught Becky on her way to the bathroom after the match. “What do you think went wrong today?” he said. “I mean, we were the better team.”

“Well, you win some, you lose some,” she said, as a coach might do when her players just hadn’t performed that day.

My father called a team meeting. “Where is the fire in your bellies? Where is the passion in your hearts?” he asked us, sounding a little like John F. Kennedy delivering a stump speech. “For your next match, I want you to remember these words: Fight! Fight! Fight!” he yelled, the words echoing through the tennis bubble.

Kristina and I tried to melt into the bleachers.

My father came to every match Yale played thereafter, even the away matches. I refused to let him ride on the big white bus with the team, so he drove behind us, like a team mascot in his little blue car with the bulldog sticker on the back, ready to cheer for his beloved Yale. My mother came with him to most of our matches, but when he insisted on driving ten hours to places as far away as Ithaca, New York, she had had enough. She loved us and all, but Ithaca?

One of the last matches of the season was an away match against Columbia. This was a big one. If we won it, we would have a shot at the Ivy title. I was playing number six; Kristina was playing four.

My father researched our opponents’ strengths and weaknesses with the precision of a CIA spy. He sent us their bios and win-loss records and inspirational quotes from football coaches. “Preparation is everything,” he said.

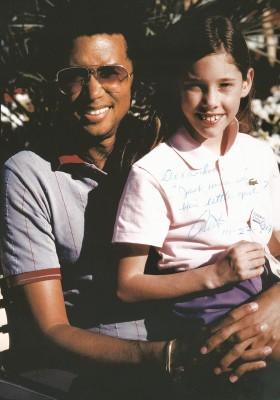

The day of the match, he drew up a guest list to come out and watch me play. As I was warming up on the court farthest from the spectators, in walked New York City mayor David Dinkins. After my family took their seats on the bleachers—my father, mother, aunt, and 90-year-old grandmother—in walked Arthur Ashe, decked out in his signature Le Coq Sportif tracksuit.

Arthur was my godfather, and I always loved seeing him. Until this day. Clearly, this former number one in the world, model of sportsmanship, and tennis legend had nothing better to do on a Saturday afternoon than to join a cheerleading squad for a bunch of college girls.

I was in the third game of the match when Arthur took a seat next to my grandmother and waved to me. I don’t know why that wave hit me, but my right arm went numb and my vision went fuzzy. I froze up and started to slice my forehand. I had been up three-love. Now it was three-one. Three-two. Three-all. The girl won the first set six-three. She skipped to her chair on the changeover, liking her odds. I sat down in my chair, tears welling in my eyes. Arthur had seen me play better than this, right? At least he knew I was a good person, that I loved animals.

It was the first game of the second set and I was now slicing both my forehand and my backhand. I could see my dad throwing his head back in his hands.

When I was trailing three-love in the second set, my father gathered up his entourage, threw in a few of my teammates who had already finished, and moved everyone to the sidelines of my court. One by one, like a line of ants marching, they came through the flap in the back of the bubble to stand directly by my court. The sign of solidarity rattled my opponent.

“Hit the ball!” my father yelled from a couple of steps away from me. Arthur bowed his head in silent support. With that, I found my topspin ground strokes again and pulled out the second set seven-five.

The third set was a blur. Time and again, my opponent would give me easy sitting ducks, where the ball is as big as a blimp, and I would hit them right back to the center of the court, too scared to do anything with the ball.

My dad was dying. After all those summers at Nick’s, how could his daughter—his surrogate son, his teammate, his DonaldAnna, who was finally playing for Yale—be such a sissy pusher?

“Put the ball away!” he yelled. “Make her move!” But the words just sounded like the distorted noise of a record played at too slow a speed, as if he were speaking underwater.

Arthur stood there, unshaken yet sympathetic, clapping when appropriate but not saying a word. I imagined him meditating during the changeovers at the US Open, driving volatile players like Connors and McEnroe crazy. Flashy play or boisterous cheering was not his style.

In my head, I could hear Nick yelling at me from behind the baseline: “Right here, dear! Move your feet, dear! Uncle Nick sees your potential, dear!”

I tied it up six-all in the third. Not only was this the deciding set, but mine had become the deciding match. The other matches were finished, and the team score was tied at four-four. All the players were now standing on our court cheering for their side. And then, after a 40-ball rally, my last soft sitter hit the top of the net and fell back to my side.

There was an audible sigh at my end of the court. Three sets and four hours after it started, I lost the tiebreaker. I was shaking, my head hung low. The Columbia teammates ran over and hugged my opponent, who had fallen to the ground as if she had won Wimbledon. My teammates came over and hugged me out of sheer sympathy. I had lost the match against Columbia and our chance at the Ivy title.

I walked to the net, shook my opponent’s sweaty hand, sat down in my chair, and burst into tears. My dad sat down and put his arm around me.

I wish I could rewrite history on that match. I spent my next two years of tennis trying to make up for it, haunted by the vision of my dad throwing back his head in anguish and Arthur’s stoic nods. People always say you learn from your losses, but until that match I never had—they had always made me more tentative, more scared to lose and to disappoint.

But sometimes hitting rock bottom can be liberating. I had just experienced the most humiliating defeat of my tennis career, and I’d done so in front of everyone I cared about most in my life, yet strangely I was fine. My mother, sister, teammates, and—perhaps most important—my father were all still proud of me. And once I realized that everything would be okay, that there would be other matches to win and lose tomorrow, the fear lifted and I played with more freedom. I found the joy and beauty in whacking around a fuzzy yellow ball. And with that I was able to reach for something deeper when I needed it, to own my game, flaws and all.

The attitude adjustment worked. Or maybe I simply got a forehand. Either way, I started beating people who had killed me love and one freshman year, and I began moving up in the lineup. By senior year I was playing number four and five, while Kristina was playing number two and three. I had the only undefeated season in the Ivies and won most improved player of the year, a signal that, yes, I may have sucked coming in, but somewhere between that Columbia match and all those buckets of forehands, I became a player.

“I knew you could do it,” my dad said when I showed him my award, a silver engraved cup that looked like a candy dish.

After graduation, I continued to play tennis for fun, but my competition days were over. Whenever I came home, Dad and I would play together just as we had all those years when it seemed to matter so much. He ran for only half my shots now, but he still painted the lines with his hard, flat forehand that glided low across the net and died on impact.

Even though we were no longer competing, he still loved to come out and watch my sister and me play, for no reason at all. He’d sneak up on us unannounced in the middle of our rally. “You’ve learned how to volley,” he’d say, and I’d look up to see him smiling at me from the sidelines.