“This is Your Country”

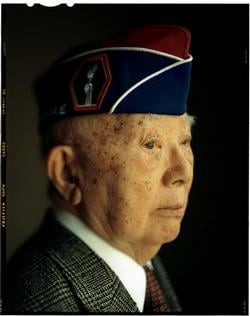

On December 8, 1941, Joe Ichiuji burned inside as he listened on a radio to President Roosevelt declare war on Japan for the attack on Pearl Harbor. The young soldier, stationed with the Army’s 41st Division at Fort Lewis near Seattle, hoped for the chance to fight for his country.

Ichiuji had been born and raised in the Northern California town of Salinas. His parents were Japanese immigrants who had come to America to start a new life. They’d opened a shoe shop and done well. California had become home.

Within weeks of Roosevelt’s speech, Ichiuji’s commanding officer handed him discharge papers and sent him packing. According to the War Department, all local Japanese-Americans were suspect in what it believed would be an attack on the West Coast.

Upon his arrival at the train station in Salinas, his parents, sister, and five brothers greeted him with more bad news: They’d been assigned to an internment camp in Arizona.

Months later, the Ichiujis arrived by train at Poston, the largest of ten American camps. Guards greeted them with machine guns and escorted them through a barbed-wire fence to their tiny room in the middle of the desert.

In 1943, the War Department—realizing that many able bodies that might aid in the war effort were languishing in the camps—decided to give Japanese-American men a loyalty test. Those who renounced the Japanese emperor and swore allegiance to the United States Army could join the 422nd Combat Team, a unit of Japanese-Americans. Ichiuji was among the first to sign up.

Before he left, his father looked him in the eye. “This is your country,” he said. “Do your best to defend it.”

Ichiuji, who now lives in Rockville, was assigned to the unit’s 522nd Battalion and fought in Italy and in northeast France near the Vosges Mountains, where a lost American battalion was surrounded by Germans. In a fusillade of bullets, Ichiuji’s unit broke through the lines and rescued 211 soldiers at the cost of some 800 casualties.

In the spring of 1945, the 522nd joined the invasion of Germany and discovered just how hellish things had been for Hitler’s enemies. In the bone-littered forests around Munich, Ichiuji’s battalion came upon Kaufering IV Hurlach, a satellite of the Dachau concentration camp. The soldiers found Jewish prisoners in striped uniforms crouched in the dirt carving strips of meat from the carcass of a dead animal.

Seeing the barbed wire and barracks, Ichiuji thought of his family, who would remain in the internment camp in Arizona until 1946.

He emptied his bags and gave the prisoners his rations.

A Reason to Live

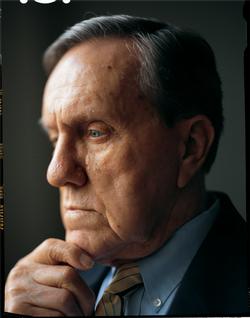

One muggy morning in August 1950, as the sun peeked over the hills around the port of Pusan in South Korea, 20-year-old Warren Wiedhahn woke up his buddy. The two Marines had spent the night on a ridge across from enemy lines, watching the darkness for signs of danger. Finally, it was breakfast time. They stood up and headed over the hill.

From an early age, Wiedhahn had a hankering to fight. His father, who was in training in 1918 just as the First World War ended, said missing it was the biggest disappointment of his life.

So when Wiedhahn came of age in 1948, he dropped out of school and, his face still wet with his mother’s tears, enlisted. Two years later, he landed with the 1st Marine Brigade in Pusan—in a country he couldn’t pinpoint on a map before—in the first big battle of the Korean War.

The sun climbed the sky as he and his friend headed for camp. Wiedhahn wiped his brow—already it was hot as hell. The hiss of a mortar round cut the silence. After the blast, he lay motionless on his back, his blood-smeared face slashed from shrapnel.

At the rear, medics told him that his partner had been killed. “Charlie was his name,” says Wiedhahn, a Pennsylvania native who has lived in Annandale for the past 40 years. “I’ll never forget it.”

Back on the front lines four days later, Wiedhahn helped US forces advance at Pusan and took part in the Inchon landing and the subsequent liberation of Seoul.

Then one morning that winter, at an outpost in the Chosin Reservoir—where temperatures dropped to 32 below—Wiedhahn was startled by the strange sound of whistles, bugles, and bells. A moment later, the mountains erupted with a wave of 100,000 Chinese troops.

Wiedhahn collected the frozen dead, snapping their limbs to stack them like cordwood on a truck. The unexpected assault forced the Americans into a bloody withdrawal to the city of Hungnam on the coast, where they were evacuated in December 1950.

Wiedhahn went on to fight in Vietnam. He retired as a colonel in 1982, but the memory of Charlie stayed with him.

Years later, Wiedhahn—whose business, Military Historic Tours, takes thousands of vets and their families back to the battlefields—returned to the ridge where he’d been wounded. Pusan, a ruin when he’d left it in 1950, was now a dazzling city of 4 million.

“You stand there on the hill and wonder why he got killed and you didn’t,” Wiedhahn says. “But one of the reasons you live is so you can give something back.”

Earning His Wings

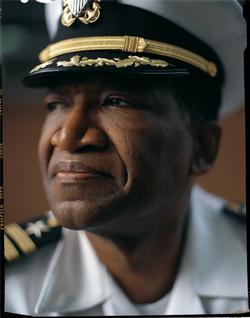

Ed Gantt paces in front of a dozen students at Frederick Douglass High School in Upper Marlboro. Gantt’s Junior ROTC class has been asked to perform color-guard duty at Andrews Air Force Base on Saturday.

“Is there anyone willing to take this responsibility?” he says, his wrinkled hands clasped behind him. The Navy captain is dressed as he has been for 40 years, in uniform. He turns and faces his students, who eye one another and the clock.

“Nobody?” Gantt says. “I thought we had a bunch of people who wanted to be leaders. Getting out of bed on a Saturday morning to do something worthwhile—now, that’s leadership.”

It was on a Saturday in 1969 at an Army recruitment station in DC that Gantt boarded a bus for Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The Prince George’s County native, who grew up scraping pennies together to buy model airplanes, was hooked by the promise that he’d be a pilot shortly after his 18th birthday.

At boot camp, Gantt suffered through pushups and indignities to try to earn his wings. When assigned to lead draftees older than he was, he was uncomfortable and gave up the responsibility—only to have his drill sergeant punish him by making him work late into the night digging a coffin-size ditch in the pine woods.

By January 1970, he was a door gunner on a Chinook helicopter flying missions in Vietnam. To Gantt, soaring over dark waters in the Mekong Delta with the doors off was like speeding down a country road in a sports car with the windows down.

By day, he fired a machine gun into the jungle, clearing the way for troops to resupply American and South Vietnamese forces. By night, he bunked with a Kentuckian who hummed Merle Haggard songs and a fellow gunner who’d been in a shootout with Los Angeles cops. This was Vietnam, and it was also his first real taste of America.

Returning from his year’s tour, Gantt enrolled at Howard University, where he played football. But the pull of flying planes was too strong. He entered the Navy to fly carrier-based jets as a copilot, and in 1985 he helped capture the hijackers of the Achille Lauro cruise ship.

Gantt went on to command the Navy’s boot camp in Great Lakes, Illinois, but in 2004 he returned to Prince George’s County to teach. Teenagers are more unruly than midshipmen, and the 57-year-old wonders if he’s making a difference in their lives. But nothing shakes him of his faith in the military to teach responsibility.

“Now, is there anyone who wants to take this color-guard duty?” Gantt asks again.

One by one, hands rise.

Mayday!

In November 1991, dark clouds drifted across the Iraqi desert near Basra where William Andrews was flying his fighter jet, preparing to drop cluster bombs.

Operation Desert Storm had taken a toll on Saddam Hussein’s Republican Guard, which had set fire to oil wells in its retreat from Kuwait. Andrews found a hole in the clouds and dipped through.

Three days earlier, Andrews had helped rescue a team of American special forces from an advancing Iraqi platoon. The Iraqis had closed to within a hundred yards of the Americans, and a stray bomb could have killed his compatriots. Back at base, Andrews and fellow airmen celebrated with backslaps and cold beer when they learned they’d saved the soldiers.

Now in the sky again, Andrews turned at a right angle to find his targets. A moment later, a blast from the ground sent his plane spinning out of control. Andrews yanked the ejection handle below his seat and in a deafening roar was launched into the air.

Floating above the battlefield, he radioed, “Mayday! Mayday!” He heard machine-gun fire and tried to steer his parachute downwind from Iraqi troops but ran out of time. He slammed into the hard sand. In the pool of his deflated parachute, he clutched his right leg. It was broken.

Sitting up, Andrews saw Iraqis with AK-47s running toward him. An Iraqi solider nearby readied a missile launcher, aiming at an American F16 flying overhead. Andrews snatched up his radio. Just as the missile blasted, he yelled into his handset, “Break right!” The plane veered. The missile missed.

Enemy bullets sleeted the sand around Andrews. He thrust his hands into the air in surrender.

During the chaos of a ground action that night, Andrews crawled away from his captors and hid in a bunker. But an Iraqi patrol found him at dawn and sent him to Baghdad, where he was interrogated and tortured.

A week later, a Red Cross plane carried Andrews and other prisoners away, with F15s at each wing. “It was like a bear hug,” says Andrews, who now teaches at the National Defense University’s War College in DC. “Like a big embrace from a loved one.”

At Andrews Air Force Base, he underwent surgery on his leg. When he awoke in the recovery room, he flashed back to the torture in Baghdad.

“I just have one question,” he asked the nurses. “Is this the United States?”

They said, “Yes.” He passed out, a smile on his face.

"We'll Never Forget What You Said"

Three months after US forces captured Saddam Hussein, Army medic Kate Norley and her security detail walked down debris-littered streets toward the University of Baghdad, where she was to meet with eight Iraqi women, students in a veterinary class. Hussein’s face was everywhere—on billboards, the sides of buildings, store windows.

The women, who still feared the fallen dictator, wanted to know everything about 20-year-old Norley: What is it like to be free? they asked. To have a president who doesn’t rape and pillage? What can we do?

Norley encouraged them to help rebuild Iraq, pleaded with them not to lose hope. She took a picture with them, her blond hair brilliant among the dark burkas.

Norley had enlisted days after 9/11. She’d planned on spending a year traveling after she graduated from Alexandria’s Episcopal High School, but as she watched the smoke rising from the Pentagon and the World Trade Center, she knew she’d found her calling.

She arrived in Iraq with the 1st Cavalry Division out of Fort Hood, Texas, as part of the first reinforcements after the US-led invasion. At the battle of Fallujah, and later at Najaf and Sadr City, she treated the American wounded and pulled dog tags from the dead, often finding pictures of loved ones tucked deep inside vests.

She also saw the challenges facing Iraqi women. During one raid, her commanding officer asked her to remove her protective gear and let her hair down to show an insurgent that a woman had helped captured him. With Norley revealed, the man screamed, “Kill me now!”

Later, when insurgents issued a reward for an American blonde, Norley cut her hair and dyed it black.

At the end of her 16-month tour, she carried home harrowing war stories but also hopeful memories—the relationships she’d built with villagers, the kids she’d taught the chicken dance, the talk she’d had with the women at the university.

This March, she watched President Bush honor an international group of women at the White House. One of them, Eaman Al-Gobory—who had been lauded for her work helping sick and wounded children in Iraq get care abroad—looked familiar. At the reception afterward, Norley approached her: “Have we met before?”

Al-Gobory smiled. “You spoke to our class in Iraq,” she said. “I want you to know we’ll never forget what you said.”

This article is from the June 2008 issue of The Washingtonian. For more articles from the issue, click here.